Where to Prepare?

Data-Driven Approaches to Hospital Mitigation in the Dominican Republic

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

Hospitals are critical assets during disasters, but their facilities are often disrupted by the event. The World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization jointly developed the Safe Hospitals Framework to promote investment in safe and resilient hospitals. The framework includes the Hospital Safety Index (HSI) evaluation guide. This tool enables ministries of health and hospital administrators to identify the structural, non-structural, and functional vulnerabilities of their hospitals to disasters. Since 2009, the Ministry of Public Health in the Dominican Republic has been using the HSI evaluation tool to assess hospitals across the nation.

In 2019, our team, which includes two members familiar with the Safe Hospitals program in the Dominican Republic, submitted a Mitigation Matters proposal to study what motivated hospital administrators to make structural, nonstructural, and functional improvements to their hospitals, including the results of their HSI evaluation. Our central purpose was to understand how and why hospitals implement mitigation practices in the absence of formal requirements. Weeks after our proposal was funded, however, the COVID-19 pandemic began and we decided to suspend the research project. As an alternative, we designed this review of the HSI evaluation data. We focused on mapping the location of hospitals that had been evaluated, with the intent to identify patterns and gaps. This report is not based on original research, but rather is a review of the literature and secondary data. We will use the results to inform the research design of a future qualitative study on the determinants of hospital mitigation. For example, the results will help us to purposively sample hospital administrators from rural and urban areas whose hospitals have varied levels of mitigation for in-depth interviews about their mitigation decision-making.

Introduction

The Dominican Republic is located on the island of Hispaniola, along with the country of Haiti. Over the past 25 years, the country has made significant progress in reducing poverty and increasing access to health services. For example, infant mortality decreased by 45%—from 39.1 to 21.5 deaths per 1,000 live births—between 2000 and 2019 (Organización Panamericana de la Salud, 20211). Despite this progress, however, notable health disparities still exist among rural and urban populations (World Bank, 20182).

The nation is also highly vulnerable to disasters due to its high exposure to natural hazards and climate-related risks. Hispaniola, situated on the edge of a tectonic plate, has an earthquake hazard classification of medium (ThinkHazard, n.d.3). In addition, its location in the Caribbean puts it in the pathway of major storms and hurricanes. Parts of the island are also highly susceptible to flooding, landslides, extreme temperatures, and drought (World Bank, 2018).

Between 1999 and 2018, the Dominican Republic was ranked 10th worldwide for human and economic losses caused by weather-related events (Eckstein et al., 20194). These adverse disaster outcomes can be linked to the country’s poor building codes, land degradation, and rapid and unplanned urban development (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, n.d.5). Previous disasters have resulted in substantial health and health system impacts. For example, when Hurricane Georges—the most catastrophic hurricane to hit the country recently—made landfall in 1998, 28% of sampled households had a family member that needed medical attention and 78% reported a family member in need of medication (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 19996). In addition, 78 health-related buildings had structural damage (Báez & Valverde-Podestá, 20017).

After a disaster, hospitals serve as a critical asset and play an essential role in the continuity of health care services, but they often lose functionality as a result of structural and non-structural damage (Kirsch et al., 20108; McGinty et al., 20179; Zorrilla, 201710). Making investments to reduce the vulnerability of hospitals to natural hazards is a strategy that alleviates the health impacts of these events (Pan American Health Organization [PAHO], 200511). Hospital mitigation has gained traction in Latin American and Caribbean countries as a way to increase hospital security and improve healthcare preparedness during hurricanes and earthquakes (Poncelet & de Ville de Goyet, 199612).

To encourage investment in safe and resilient hospitals, the World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization have jointly developed the Safe Hospitals Framework (World Health Organization [WHO] & PAHO, 201513; PAHO, n.d.14). This framework identifies preparedness and mitigation practices that hospitals can implement to safeguard their facilities and ensure they are able to operate safely during disasters. It also provides a method for planning interventions based on identified needs (PAHO, n.d.). Recommended interventions include developing hospital disaster risk management systems, constructing safe hospitals, implementing efficient and reliable energy supplies, managing equipment and supplies, and strengthening the hospital workforce for emergencies.

The Ministry of Public Health in the Dominican Republic adopted the Safe Hospital Framework in 2009 (Morales-Cartagena, 201815). A decade later, in 2019, our team, which includes two members familiar with the Safe Hospitals program in the Dominican Republic, submitted a Mitigation Matters proposal to study what motivated Ministry officials and hospital administrators to make structural, nonstructural, and functional improvements to their hospitals, including the results of their HSI evaluation. Our central purpose was to understand how and why hospitals implement mitigation practices in the absence of formal requirements. Our research design included in-person, semi-structured interviews with hospital administrators in the Dominican Republic. Our proposal was approved just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the ensuing months, we decided to suspend our research plans because it was neither feasible nor appropriate to contact hospital leaders as they were focused on the response to the pandemic.

As an alternative to our proposed research project, we decided to review the Dominican HSI evaluations that had been completed by 2018. We focused on mapping the location of HSI-evaluated hospitals, with the intent of identifying patterns and gaps. This report is not based on original research, but rather is a review of the literature and secondary data.

Literature Review

Safe Hospital Framework’s Hospital Safety Index

The Hospital Safety Index (HSI) is an evaluation tool developed by WHO and PAHO to accompany the Safe Hospital Framework (WHO & PAHO, 2015; PAHO, n.d.). The HSI includes an evaluation guide and forms that hospital administrators, ministries of health, or other stakeholders can use to evaluate hospital vulnerabilities to disaster. Evaluations are conducted by teams of evaluators who have been extensively trained in the HSI process. Upon completing the evaluation, the team of evaluators gives the hospital a final Safety Index score of A, B, or C, the three categories of safety that indicate whether a hospital is vulnerable to losing all or part of its ability to function during a disaster. Table 1 below reproduces the definitions of Categories A, B, and C from the PAHO Safe Hospitals website.

Table 1. Hospital Safety Index’s Three Categories of Safety

| Category A | Facilities deemed able to protect the life of their occupants and likely to continue functioning in disaster situations. | Category B | Facilities can resist a disaster but in which equipment and critical services are at risk. | Category C | Facilities where the lives and safety of occupants are deemed at risk during disasters. |

While the Safe Hospital Framework and HSI evaluation tool has been used extensively at the individual hospital level, it remains underutilized as a means to assess hospital preparedness at the community or regional level. In a recent study, the Safe Hospital Framework was used in tandem with an earthquake simulation that assessed the impacts of hospital disruptions on a large urban scale; specifically on a post-earthquake operating room security in Lima, Peru (Ceferino et al., 202016).

Hospital Safety Index Evaluations in the Dominican Republic

In 2010, one year after the Dominican Ministry of Public Health adopted the Safe Hospital Framework, it began training evaluators to assess the vulnerability of the nation’s hospitals using the HSI evaluation toolkit (Morales-Cartagena, 2018). As of 2018, 167 evaluators had been trained and 88 hospitals in the public health care system had been evaluated. Of those 88 hospitals, more than 50% of the hospitals assessed received a C classification and none received an A. Moreover, the assessment showed that as many as two-thirds of regional and municipal hospitals that had been evaluated would not be available if a disaster struck them. The evaluations suggest that significant investments are needed to reduce hospital vulnerability to disasters across the country.

Guiding Questions

We formulated guiding questions for our review, rather than research questions. The following questions guided our assessment of the HSI evaluation data:

- Where are the evaluated hospitals located? How are the evaluations distributed across municipalities? What types of municipalities lack evaluations?

- What is the average distance from the city center to the nearest hospital with “B” or “C” classifications?

Review Process

We gathered secondary data from two sources: (1) The Safe Hospital Framework evaluations in the Dominican Republic and (2) census data from the World Population Review (202217). We reviewed and input the data into an Excel database and then conducted a geographic information system (GIS) analysis. Each of these steps is described in more detail below.

Secondary Data

Safe Hospital Framework Evaluations

The Ministry of Public Health Directorate of Risk Management and Disaster Attention provided us with the evaluations of 56 hospitals that had been reviewed as part of its Safe Hospitals Program. All evaluated hospitals were public. We input data from the HSI evaluation forms (which were provided to us as PDFs) manually into an Excel database.

Municipal and City Population Data

We used 2010 census from the World Population Review (2022) to gather population data on Dominican cities. The data showed the nation had 71 cities with 2010 populations of 10,000 people or more. These cities were selected for further analysis. Next, we stratified the cities into groups based on their population size (10,000 to 49,999; 50,000 to 149,999; 150,000 to 499,999; greater than 500,000). In our analysis, we reviewed and mapped the number of HSI-evaluated hospitals in all municipalities. We limited, however, our analysis to the 71 cities in the Dominican Republic with populations greater than 10,000 people.

The reader should note that the terms municipality and city have different meanings and uses in the Dominican Republic than in other places, like the United States. As of 2010, the 29 provinces in the Dominican Republic are divided into 155 municipalities (De La República Dominicana, 202318). Municipalities incorporate both urban and rural territories. Large urban areas within municipalities are classified as cities. Legally, these large cities are frequently designated as “municipal districts.” In some cases, a municipality can have more than one city or municipal district.

Geographic Information System Analysis

We manually geocoded hospital locations in Google Maps, confirmed these locations with members of the investigative team based in the Dominican Republic, and entered these coordinates into the Excel database. Next, we used QGIS, an open-source geographic information system software, to visualize the 56 evaluated hospitals, municipal borders, city locations, city population size, and HSI hospital evaluation scores.

For each city, we calculated the distance from the city center to the nearest B- and C-ranked hospitals using the QGIS distance matrix tool. We then averaged these calculated distances across cities in the same size stratification.

Results

Distribution of Evaluated Hospitals Across Municipalities

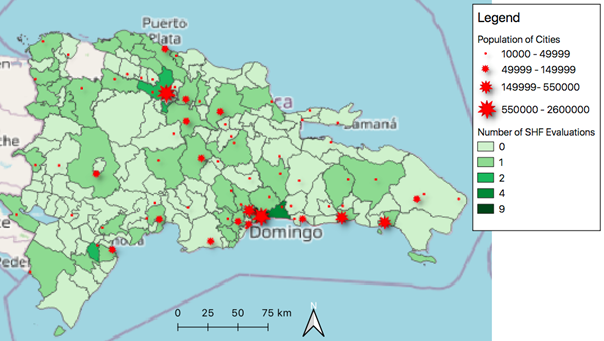

Figure 1 displays a map of Dominican municipalities. The green shading indicates how many hospitals have been evaluated with an HSI classification in each municipality, with light green showing municipalities with no evaluations and the darkest green showing municipalities with nine evaluations. The map also depicts in red the 71 cities in our sample, stratified by population size. To preserve hospital confidentiality, we did not include the point locations of the evaluated hospitals in the map.

Figure 1. Hospitals Per Municipality That the Ministry of Public Health Has Evaluated as Part of the Safe Hospital Framework Program

Average Distance to Evaluated Hospital

Table 2 depicts the average distance from the city center to the nearest evaluated hospital with a “B” or “C” classification. (No hospitals received “A” classifications.) Smaller cities of 10,000 to 49,999 residents had the longest average distance (28,926 meters) from the city center to the nearest hospital with a B score. The distance in medium-sized cites of 50,000 to 149,999 residents was only slightly shorter at 27,726 meters. Larger cities with 50,000 to 499,999 residents had the shortest distance (15,327 meters) between the city center and the nearest “B” hospital. The largest cities (with populations over 500,000 residents) had a slightly longer distance from city center to "B" hospital (17,933 meters). But these same cities had the shortest distance from city center to a "C" hospital (2,237 meters). The longest average distance to a "C" hospital was in small cities (18,251 meters.) Medium and large cities both had a distance of around 12,000 meters to a "C" hospital. In general, the average distance decreased as population size increased.

Table 2. Average Distance From City Center to Nearest Hospital With “B” or “C” Classification

| 10,000-49,999 | 28,926 | 18,521 |

| 50,000-149,999 | 27,726 | 12,765 |

| 150,000-499,999 | 15,327 | 12,402 |

| 500,000-2.6 million | 17,933 | 2,237 |

Conclusions

Our review provides information about the locations of hospitals that have undergone an HSI evaluation in the Dominican Republic by 2018. However, not all hospitals have been evaluated, with relatively few in large urban centers. Most hospitals that have been evaluated are located in smaller cities with 10,000-49,999 residents. As such, we recommend additional and more geographically representative assessments of hospitals using the HSI.

Limitations

The Dominican Ministry of Public Health’s evaluations of its hospitals using HSI is ongoing. Our report is based on evaluations completed as of 2018. Additional evaluations have taken place and some evaluated hospitals have begun to invest in mitigation. Moreover, the HSI evaluator teams have not yet evaluated all public hospitals and no private hospitals have been evaluated. As a result, our analysis may not be based on up-to-date data. We did note, however, that the evaluated hospitals did tend to serve lower-income, uninsured residents.

We were also not able to gain access to data on the total number of hospitals within each municipality. This hindered our ability to analyze which municipalities had the lowest proportions of their hospitals evaluated. As a result, we could not identify with confidence those municipalities that lacked evaluations.

Our GIS analysis also was limited by lack of access to road and traffic data. We calculated the distance to the nearest evaluated hospital using “as the crow flies” measurements. The actual travel distance via road in real world situations may be substantially greater, compounded by traffic delays. Also, city center is limited in its ability to represent the residential locations of most residents.

Finally, our review of the HSI forms suggested there may be variation in how evaluator teams assigned the overall “A,” “B,” or “C” safety classifications to hospitals. We have no information about evaluator interrater reliability.

Future Research Directions

We plan to use the map of evaluated hospitals to inform future purposive sampling approaches for a qualitative research project on determinants of hospital mitigation. For example, we may use the mapping technique to curate a sample of hospitals divergent on level of preparedness, located in different sized cities, or where additional investment in mitigation might increase healthcare access in a disaster. We have already used our review findings to develop an interview guide for in-depth interviews with hospital administrators.

Future quantitative or GIS analyses should integrate bed capacity, hazard information, socio-economic information, road information, and distance between facilities. In addition, future assessments should identify how many hospitals have not yet been evaluated using the HSI tool.

References

-

Organización Panamericana de la Salud. (2021). Salud en las Américas+. Perfíl de Pais. República Dominicana. https://hia.paho.org/es/paises-2022/perfil-republica-dominicana ↩

-

World Bank. (2018). Dominican Republic—Systematic Country Diagnostic. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/980401531255724239/dominican-republic-systematic-country-diagnostic ↩

-

ThinkHazard. (n.d.). Dominican Republic. Earthquake Hazard Level. Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://thinkhazard.org/en/report/72-dominican-republic/EQ ↩

-

Eckstein, D., Künzel, V., Schäfer, L., & Winges, M. (2019). Global Climate Risk Index 2020. Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2018 and 1999 to 2018. GermanWatch. https://www.germanwatch.org/en/17307 ↩

-

Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery. (n.d.). Dominican Republic. World Bank. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.gfdrr.org/en/region/dominican-republic ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999, February 12). Needs Assessment Following Hurricane Georges—Dominican Republic, 1998. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 48(5), 93-95. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm4805.pdf ↩

-

Báez, A. A., & Valverde-Podestá, A. (2001). Overview Of the Dominican Red Cross Emergency and Relief Operations Following Hurricane Georges. The Internet Journal of Rescue and Disaster Medicine, 3(1). http://ispub.com/IJRDM/3/1/12882 ↩

-

Kirsch, T. D., Mitrani-Reiser, J., Bissell, R., Sauer, L. M., Mahoney, M., Holmes, W. T., Santa Cruz, N., & de la Maza, F. (2010). Impact on hospital functions following the 2010 Chilean earthquake. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 4(2), 122–128. ↩

-

McGinty, M. D., Burke, T. A., Resnick, B., Barnett, D. J., Smith, K. C., & Rutkow, L. (2017). Decision Processes and Determinants of Hospital Evacuation and Shelter-in-Place During Hurricane Sandy. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 23(1), 29–36. ↩

-

Zorrilla, C. D. (2017). The View from Puerto Rico—Hurricane Maria and Its Aftermath. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377(19), 1801–1803. ↩

-

Pan American Health Organization. (2005). Safe Hospitals: A Collective Responsibility. A Global Measure of Disaster Reduction. https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2010/HS_Safe_Hospitals.pdf ↩

-

Poncelet, J. L., & de Ville de Goyet, C. (1996). Disaster preparedness: institutional capacity building in the Americas. World Health Statistics Quarterly, 49(3–4), 195–199. ↩

-

World Health Organization & Pan American Health Organization. (2015). Hospital Safety Index Guide for Evaluators, 2nd ed. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548984 ↩

-

Pan American Health Organization. (n.d.). Safe Hospitals. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.paho.org/en/health-emergencies/safe-hospitals ↩

-

Morales-Cartagena, Ashley. (2018, November 20-21). Experiencia Hospitales Seguros en la República Dominicana [Conference Presentation]. VII Reunión Alianzas Público-Privadas para la Reducción del Riesgo de Desastres en América Latina y el Caribe. Secretaria Permanente del Sistema Económico Latinoamericano y del Caribe. Ciudad de México, México. http://www.sela.org/media/3205368/experiencia-hospitales-seguros-en-la-republica-dominicana.pdf ↩

-

Ceferino, L., Mitrani-Reiser, J., Kiremidjian, A., Deierlein, G., & Bambarén, C. (2020). Effective plans for hospital system response to earthquake emergencies. Nature Communications, 11(1), 4325. ↩

-

World Population Review. (2022). Population of Cities in Dominican Republic. https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/cities/dominican-republic ↩

-

De La República Dominicana PO. Provincias, Municipios y Distritos Municipales - Portal Oficial del Estado Dominicano. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.dominicana.gob.do/index.php/e-municipios/e-localidades/2014-12-17-20-04-43. ↩

Kahn, A. S., Morales-Cartagena, A., Vickery, J., Marquez, P. I., & Errett, N. A. (2023). Where to Prepare? Data-Driven Approaches to Hospital Mitigation in the Dominican Republic (Natural Hazards Center Mitigation Matters Research Report Series, Report 16). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/mitigation-matters-report/where-to-prepare