Communication and Coordination Networks in the 2023 Kahramanmaras Earthquakes

Publication Date: 2024

Abstract

This report presents findings from a quick response study of communication and coordination networks functioning in response to the February 6, 2023 Kahramanmaras Earthquakes in Turkey. Communication and coordination are central to mobilizing response operations under critical time constraints. Framed within the literature of complex adaptive systems, this study focused on decision-making among interacting organizations that operated during this event and the flow of information within and among organizations that guides collective action. Using exploratory case study methods, this report addresses four basic tasks to: (1) characterize the context in which the earthquakes occurred, including public awareness, policies, and practices to reduce seismic risk; (2) identify technical communications networks that functioned during the first three weeks of response operations, including principal nodes of connection and missing links in the process; (3) identify organizational coordination networks and information used to guide technical disaster operations networks; and (4) identify gaps in technical and organizational networks as responding organizations struggled to operate in a disaster-degraded context. Defining the limits of both technical and organizational networks operating under extreme conditions is critical to understanding how these networked systems—technical and organizational—can be scaled and strengthened to function more effectively in large-scale, extreme events. The international research team also provides an update on field research needs to the Social Science Extreme Events Research community based on onsite observations.

Introduction

On February 6, 2023, two major earthquakes devastated cities and villages in southern Turkey and northern Syria. The first earthquake, a magnitude 7.7, struck at 4:17 a.m. local time in the Pazarcik district of Kahramanmaras Province. The second earthquake, a magnitude 7.6, occurred at 1:24 p.m. on the same day in the Elbistan District (Erdik et al., 20231). Both earthquakes had destructive impacts on the region. The earthquakes affected the provinces of Kahramanmaras, Hatay, Adiyaman, Gaziantep, Sanliurfa, Diyarbakir, Adana, Osmaniye, Kilis, Malatya, and Elazig. Approximately 13 million residents in 11 provinces were directly impacted by the earthquakes, but the cascading consequences of the disaster were experienced nationwide.

According to the Turkey Disaster and Emergency Management Authority, known by the Turkish language acronym AFAD, the losses in the two earthquakes were sobering (2023a2). The earthquakes claimed more than 50,783 lives and left 115,353 individuals injured in Turkey, and took more than 8,000 lives across the border in Syria. Based on the findings of the report, a total of 37,984 buildings collapsed completely, while more than 240,000 buildings were rendered unusable. The report also stated that aftershocks from the two earthquakes continued for weeks, with a total of 33,591 aftershocks recorded during the three-month period. The total cost of the damages from the earthquake sequence was estimated at approximately $103.6 billion USD (Turkey Strategy and Budget Directorate, 20233). Considering these data, the Kahramanmaras Earthquakes were the most devastating socially and economically in the history of the Turkish Republic.

The first three days following the quake were the most urgent and challenging in terms of saving lives and organizing response operations. The earthquakes shattered the existing infrastructure for communications, impeding access to information technologies and disrupting coordination among the organizations and institutions trying to collaborate in search and rescue operations. The area most severely impacted by earthquakes included Kahramanmaras, Adiyaman, Hatay provinces and the Gaziantep districts of Islahiye and Nurdagi.

Direct observation of the events following the Kahramanmaras earthquakes revealed a gap in knowledge of seismic risk among different groups in the population—specifically professional experts in engineering, urban planning, and disaster management—and actions taken to reduce that risk by government agencies, construction companies, local building owners, and residents. This study seeks to identify the networks of communication and coordination through which information about seismic risk flows or gaps in this critical process due to missing links.

Literature Review

This study is framed within the extensive literature on complex adaptive systems and considers response operations to disasters as a dynamic, adaptive system of interrelated actors, with multiple points of decision-making authority and action across jurisdictional scales (Kauffman, 19934; Glass et al., 20115; Comfort, 19996; Comfort, 20197). Within this broad framework, this study focuses on decision-making in urgent events (Comfort, 20078; Hutchins, 19959; Kahneman, 201110). The study also draws on a collection of research studies of previous disasters (Erkan et al., 201611; Celik & Corbacioglu, 201012; Celik and Corbacioglu, 201613; Celik and Corbacioglu, 201814; Ertan & Çarkoğlu, 202215), analyses of policy change (Balamir, 200116; Gülkan, 200117) and rapid urbanization (Danielson & Keleş, 198518) in Turkey. Three themes drawn from these divergent literatures underlie the basic assumptions of this study. The first is that modern Turkish society is complex and has evolved over centuries of diverse and conflicting modes of governance, with some components of the population changing rapidly while others change at a much slower pace (Keleş, 198819; Keleş, 202220). The second theme is that technology has played a catalyzing role in rapid urbanization and changing culture, reflecting a fragmented society operating on different scales of time (Balamir, 2001; N. Karanci, personal communication, March 6, 2023). The third theme is a continuing struggle for democratic governance in a nation with a history of episodic reversals countered by demonstrations of civil resistance (Erkan et al., 2016; McGrath, 201521).

Each of these themes illustrate the vital role that communication processes play in sharing information broadly through communities to initiate collective action. Coordination follows in areas where communication is vital and strong, but flounders when there are gaps in communication and groups are left out of the process of mitigating risk that affects the whole community. These themes document the collective cognition of risk as the first step in initiating collective action to reduce shared risk within the society (Comfort, 2007; Comfort & Rhodes, 202222). Without shared cognition of risk among all groups—professional experts, government officials, private businesses, construction companies, community organizations, and residents—society can fragment into isolated groups, communication can falter, and coordination will fail. At such a point, control of the risk situation will disintegrate, and collective action cannot be achieved. Although this brief field study focuses on Turkey, the same patterns of interaction among the processes of cognition, communication, coordination, and control can be observed in other countries operating under stressful conditions (Comfort and Rhodes, 2022; Ko, 202323).

Research Questions

The gap between knowledge and action in achieving coherent, effective risk reduction in societies vulnerable to seismic risk was apparent in the 11 provinces affected by the 2023 earthquakes, as well as at national and municipal levels of operation. Four research questions framed this study:

What were the primary means of communication used by emergency personnel, community groups, and residents during the first three weeks following the earthquakes?

What were the principal nodes through which communication flowed during the first three weeks following the earthquakes and what gaps in communication were observed among relevant groups during this period?

How did the pattern of communication affect the coordination of actions among emergency personnel, community groups, and residents during the first three weeks?

How did the patterns of communication and coordination change over the first three weeks, if at all?

These basic questions trace the rate of change in communications among the different parties and identify points where communication facilitated interagency coordination, as well as points where gaps in communication hindered effective mobilization of collective action.

Research Design

To characterize the gap between knowledge and action in Turkey, we conducted an exploratory case study (see Yin, 201624) into the communication and coordination practices observed during the response operations to the 2023 Kahramanmaras Earthquakes. We used three methods of data collection. First, we conducted a review of news reports, professional reports of disaster operations, including search and rescue activities, and existing policy and legal documents, focusing our study on Turkish cities and villages. The news reports provided information about the conditions in the damaged areas of southern Turkey, while professional reports and studies (Erdik, 2001; Gülkan, 2001, 201825) assessed the knowledge of seismic risk generally within Turkish society and the actions taken in practice based on such knowledge. Second, we conducted a set of 23 semi-structured interviews with knowledgeable experts and community leaders in Turkey about urban planning, building construction, communication platforms, response operations, field operation personnel, and the provision of community services to the affected communities. Third, we directly observed earthquake damage and conducted visual assessments of the physical facilities and field operations that provided services for housing, health care, nutrition, education, water, and sanitation to residents remaining in the damaged communities.

Researcher Positionality

Our small team consisted of three members: Louise Comfort, who has a background in public policy and field experience in earthquake extreme events; Burcak Basbug Erkan, a statistician with experience in disaster management; and Suleyman Celik, who has a background in public administration and experience in studying earthquakes. All three researchers share knowledge of complex adaptive systems and decision-making under uncertainty.

Study Site and Access

The study focused on cities in Kahramanmaras, Hatay, and Adiyaman provinces, which were heavily damaged, and included direct observation of other cities in the region that experienced scattered damage. After our field site visits, we continued to follow news reports and reports from professional teams who studied different aspects of damage assessment and response operations.

Initial interviews with professional experts were conducted in Ankara on March 6 and 7, 2023. They were essential in gaining access to local officials in Gaziantep Center and its districts, Islahiye and Nurdagi; Kahramanmaras Center and its district Pazarcik; Adiyaman and its district, Gölbasi; and Hatay and its districts of Kirikhan, Defne, Antakya, and Samandagi. Academic colleagues in the public administration field contacted their former students who had professional experience in the earthquake-affected region and assisted us in scheduling interviews with practicing managers at field sites. One team member connected us with colleagues from AFAD working in the field, and they graciously met with us at operations centers in Gaziantep and Kahramanmaras. Other contacts in Hatay were identified through former students and colleagues of Turkish members of our team.

Data Collection

Data collection included two types of inquiry, documentary review and semi-structured interviews with professional experts and operational personnel. We conducted a review of the documents governing communication processes and the policies of public agencies and private companies that provide communication services during extreme events. These records included reports from Turkish and English news outlets that documented the actions of businesses and nonprofit organizations that often are not included in public accounts. We sought to trace the flow of information through the network of organizations and community groups as they engaged in response operations in the damaged region. Using limited resources, we identified key nodes in the networks that circulated information to local communities, as well as gaps in the networks that left communities without knowledge or resources to support response operations in a timely manner. We used this review to identify field organizations and personnel engaged in operations who could report candidly on field conditions.

Semi-structured Interviews

As noted above, we conducted 23 semi-structured interviews with professional experts, local officials, disaster managers, nongovernmental organization managers engaged in service delivery, and community leaders. Our unit of analysis was the organization, so we did not collect personal information from any of our interviewees and promised confidentiality to enable them to speak candidly regarding their experience and observations. We developed an interview protocol that we used to guide the conversation, adapting it to local contexts when necessary.

Since our time in the field was limited to three days in early March and two days in early May, we worked to identify key personnel engaged in field operations in critically damaged cities and towns. We used a purposive sample, as we sought to identify the key sources, distributors, and recipients of information disseminated to communities regarding seismic risk before, during, and immediately after the earthquakes. The interviews took place in field offices on site, as well as in the offices of professional experts and managers in Ankara. We had remarkably open access to operational personnel in the field who spoke candidly about their observations and experience in this extreme event. The interviews varied in duration from 50 minutes to several hours, and the field interviews often included a guided tour of the operations headquarters, storage facilities, damaged city sectors, or field activities in action. We took notes during the interviews to document the comments of the field personnel and our own observations of field conditions for later analysis.

Data Analysis

Before leaving for Turkey for field work, the research proposal and interview protocol were submitted to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of California, Berkeley. Since we defined our unit of analysis as the organization, the Berkeley IRB determined that our study did not require protection of personal information. This determination meant that we could use notes from our interviews and direct field observations to analyze the conditions we observed. We transcribed our notes and shared them among our small team, correcting and clarifying the statements among all three researchers. We then used systematic methods of content analysis to identify coherent themes and recurring issues as reported in our field interviews, and in response to the research questions we used to guide the study. We used the interview data to validate official reports and news analysis. For this qualitative data analysis, we checked and counter-checked findings among our three-member research team, and compared them to known reports of seismic and social risk in Turkey.

Context of Seismic Risk, Building Codes, and Community Preparedness in Turkey

To comprehend the scale of the disaster, we assessed the societal context in Turkey before the earthquakes occurred, including recognition of seismic risk as a major hazard, status of building codes developed to minimize the risk, degree to which building codes were enforced, and general level of community awareness and actions taken to mitigate risk.

Assessment of Seismic Risk in Turkey

Turkey has experienced many earthquakes in its history, including a striking sequence of events since the 1990s (see appendix). The devastating 7.4 magnitude Marmara earthquake on August 17, 1999, followed by a 7.2 magnitude quake in the Düzce-Kaynasli region on November 12, were milestones for implementing major changes in disaster risk reduction and risk management in Turkey. These two events triggered the redesign of codes and establishment of the Turkish Catastrophe Insurance Pool (TCIP), which was the first public-private partnership insurance scheme in a developing country (Basbug Erkan & Yilmaz, 201526). In October 2011, a major earthquake in the city of Van, in eastern Turkey, tested the capacity building efforts that had been implemented since 1999. Investment in equipment, personnel training, and disaster management since 1999 showed improved performance in response operations in Van in 2011 (Basbug Erkan et al. (201527). The TCIP, as designed, responded to claims arriving from policy holders in disaster-affected areas.

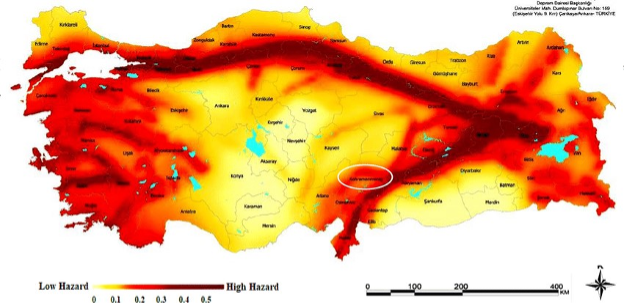

Yet, the consequences of the Kahramanmaras Earthquakes exceeded all previous efforts at preparedness. Scientists had reported that a seismic gap in the Kahramanmaras region could cause a significant earthquake, as shown in Figure 1. The city of Antakya had previously experienced devastating quakes, with the last major earthquake occurring almost 500 years ago. Seismologists had systematically documented the Eastern Anatolian Fault Line that lies beneath city centers in Gaziantep, Kahramanmaras, Adiyaman, and Hatay provinces (Lund, 202328).

Figure 1. Revised Seismic Hazard Map of Turkey in use since 2018

Note. The East Anatolian Fault is the dark red area slanting diagonally at the right, and the white circle denotes the area affected by the 6 February 2023 earthquakes. Source: AFAD, https://www.afad.gov.tr/turkiye-deprem-tehlike-haritasi

Building Codes and Enforcement to Minimize Seismic Risk

The current Turkish Building Earthquake Code was revised from previous codes in 1998, 2000, and 2007. Published in the Official Gazette of the Republic of Turkey (Turkish Building Earthquake Regulation, 201829), the revised code became legally binding on January 1, 2019. In Turkey, the central government establishes the laws at the national level, but the local governments implement these laws in cities and towns. Seismic safety and design are among the main responsibilities of local municipal governments. A regulation known as Decree No. 595 outlined building requirements for construction in the 27 seismically risky provinces, which included those affected by the Marmara and Düzce earthquakes. That decree was replaced by Law No. 4708 (Law on Construction Supervision, 200130), which specifies the requirements of construction supervision.

Not only did buildings built before the existing 2001building code fail in the Kahramanmaras Earthquakes, but newer ones did as well. For example, the Ronesans Residence in Hatay, built in 2012, collapsed, killing hundreds of people (Mourenza, 202331). It is not whether the construction is old or new that matters, but whether the construction is built according to engineering regulations and on solid ground.

Community Awareness, Preparedness, and the Capacity of Local Organizations

In 2020, AFAD began developing the Turkey Disaster Risk Reduction Plan, a national disaster risk reduction plan to be adopted by all 81 Turkish provinces and tailored to their specific hazards. Kahramanmaras was selected as the pilot province to begin implementation and, in preparation, developed the first provincial-level disaster risk reduction plan. The plan focused on how to increase community awareness, build capacity for collective action in extreme events, develop a road map toward resilience, and support informed communication from trusted professional sources to prepare for a potential earthquake. On December 26, 2022, the stakeholders met in Kahramanmaras to review the provincial plan and determine future actions. Ironically, the plan was not implemented before the Kahramanmaras Earthquakes.

The disaster risk reduction plan included municipalities, district governors, local representatives of national agencies, journalists, local AFAD teams, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and the Turkish Red Crescent. It was designed to be a strong network of relevant actors that have specialized capacities and deploy their own personnel and equipment.

Findings

Findings from our field study include direct observation of both technical conditions and organizational operations in the provinces of Gaziantep, the center and districts of Islahiye and Nurdagi; Adiyaman and its district of Golbasi; Kahramanmas Center and its district of Pazarcik, as well as Hatay and its districts of Kirikhan, Defne, Antakya and Samandagi.

Technical Infrastructure

After the first three days of initial chaos, communication systems were substantially reinstated. Search and rescue operations were extensively underway, and access to communications and information tools was established to support recovery efforts. Timely and precise dissemination of information is crucial for coordinating recovery operations effectively, but interdependence between technical and organizational systems limited functionality in both.

Damage to Transportation Systems

The earthquakes caused major damage to roads and highways, making it difficult for emergency responders to reach the affected areas. The condition of the roads, and especially damage that affected about 140 miles of the main route to the earthquake-affected provinces significantly hindered access to the Islahiye and Nurdagi districts in Gaziantep, as well as the districts of Kirikhan, Defne, Antakya (central), and Samandagi in Hatay. Additionally, damage to Hatay Airport prevented air travel, making it impossible to provide aid from the air. In March, 2023, one month after the earthquakes, we could access all these districts through the main road; yet, we witnessed streets within the cities that were still unusable due to uncleared debris.

Power Outages

The earthquakes caused power outages in many areas, making it difficult to operate communications and other equipment. In some places, electricity was cut off due to safety concerns. A month after the earthquakes, electricity had still not been fully restored in Golbasi, location of the district governorship and municipal building, in Adiyaman province.

Damage to Telecommunications Networks

The earthquakes also caused significant damage to telecommunications networks, making it difficult to communicate with search and rescue groups and with affected residents in the region. Interviewees reported that standard communications did not work on the first day after the earthquakes, but worked in limited areas on the second and third days in some cities.

After the earthquakes, most of the base stations for mobile phones were destroyed along with the buildings on which they were mounted, so mobile phones became unusable in the early hours and days of disaster response. After operators for Global System for Mobile communication (GSM) sent vans loaded with portable communications equipment to the damaged areas, cell service was largely reestablished and mobile phones became an important communication tool in local areas. However, it took three to four days for the mobile communications vans to reach the local areas, as the road damage caused by the earthquakes limited transportation. Interviewees reported that without adequate cell tower coverage, communication problems lasted up to a week in the center, districts, and villages of Hatay province, hindering rescue operations.

Novel Communications When Planned Networks Failed

The availability of alternative communication channels is vital to ensure an uninterrupted decision-making process when planned communication fails. Several alternative channels were observed in field operations.

Satellite Phones

Search and rescue teams had satellite phones for use in the event of a disaster. However, the functions of the local rescue teams were also disrupted by the earthquakes and they were not able to access their communications equipment. Rescue teams from outside the earthquake areas brought satellite telephones with them to initiate rescue operations, but in limited quantities and exclusively for the use of the teams that brought them.

Disaster Information System Applications

According to information shared by AFAD officials and NGO representatives, including the Turkish humanitarian organization ANDA, AFAD set up a network that brought together international, domestic and NGO search and rescue teams. ANDA, a nonprofit organization based in Ankara, confirmed that the search and rescue teams primarily used their own information systems, which were then integrated with the AFAD system. This arrangement enabled the tracking of actions taken throughout earthquake operations, which helped to identify what equipment and rescue team assistance was needed and where. Yet, the AFAD system faced recurring limitations, particularly in Hatay and its districts, due to the disruption of the communications and power infrastructure during the initial days of response.

Internet, WhatsApp, and Social Media

Based on interviews with field personnel, international, domestic, and nonprofit search and rescue teams largely relied on WhatsApp for local communication, both internally and with other officials. During the earthquakes, residents in the area primarily used WhatsApp groups for communication. The widespread power outages and disruption of Internet services posed serious challenges to communication. In areas where electricity was restored by the second or third day, residents sought assistance using WhatsApp and social media platforms. Twitter played a significant role, as we learned from a creative application in the Pazarcik district. Public organizations arriving from Kirikkale province prioritized the restoration of electricity. Once power was reinstated in Pazarcik, they used signals received over the Internet indicating the use of Twitter to locate people in rural areas and send aid via helicopters to isolated villages.

Mobile Phone Stations

In response to the damage incurred by base stations for mobile phones, GSM operators sent portable communications units to the region. For example, Turkcell stated that they sent approximately 250 portable base stations to the area because more than half of the local base stations were rendered inoperative and the remaining ones could not function due to power outages (Nebil, 202332). As Turkcell’s employees in the region were also affected by the earthquakes, they had to move their vehicles to locations outside the earthquake region to access cell service. Getting these vehicles on the road took a day, delaying access to the region and restoration of the system's functionality. Accessing Hatay and its districts took even more time.

Drones

Drones captured aerial images of the area, revealing the extent of the damage, and were used in damage assessment efforts. From the first day, videos captured by drones and helicopters were shown on television, enabling all citizens to see detailed images from the region.

Coordination Networks

Technical networks supporting communication were critical to enabling the organizational networks that could provide needed services to the residents affected by the earthquakes. As communications were restored, networks of support could begin to function. Given the severity of damage and wide region affected, extensive organizational assistance evolved to meet social/economic/health/psychological needs.

Local Capacity in Damaged Cities

The most crucial principle in successfully managing a disaster is increasing the technical and organizational capacity of local organizations to ensure that local functions can be quickly reinstated after the disaster. In the cities affected by the Kahramanmaras earthquakes, local capacity was severely limited. Damage to technical infrastructure hindered the ability of emergency response teams to reach the affected areas and deliver aid. The local governments in the impacted regions were overwhelmed due to the magnitude of the disaster. In such situations, the anticipated course of action for the nearest provinces or districts to provide assistance. Due to the widespread impact of the earthquakes, however, assistance from neighboring provinces was unattainable, requiring support from the central government and international organizations.

External Support from Provincial, National, and International Organizations

Immediately after the first earthquake occurred in Pazarcik, AFAD issued a Level 4 disaster declaration, classifying the event with highest severity that warranted a call for international assistance (ReliefWeb, 202333). Immediate reports from affected areas cited the magnitude of disaster, revealing that local resources alone could not cope with the situation.

As stated in an AFAD press bulletin (2023b34), a combined total of 18,040 vehicles, encompassing construction machinery such as excavators, tractors, cranes, dozers, trucks, water tenders, trailers, graders, and vacuum trucks, were dispatched to the impacted zones and actively engaged in operations on-site. Moreover, 38 governors, more than 160 local authority representatives, 68 provincial directors, and 19 senior AFAD officials were assigned to manage the affected areas. International search and rescue teams from 69 countries offered assistance to the region. As the international teams arrived, each was paired with a Turkish search and rescue team to provide local knowledge and translation skills, enabling the collaborating teams to work more effectively in searching for survivors.

Informal Emergent Groups in the Damaged Region

After the earthquakes, local people, volunteers, and NGOs formed spontaneous groups to help. Some searched for survivors using basic tools, while others gave out food, water, and shelter with the help of government assistance teams and NGOs. Religious foundations also played a significant role. Previously established groups for disaster intervention in the region primarily focused on attending to their own immediate needs. Consequently, local efforts fell short, leaving residents inadequately supported. Interviewees reported that neighbors took part in rescue activities using their bare hands to dig through the rubble to reach survivors. The interviewees stated that they felt helpless in the face of extensive destruction. They recounted instances where trapped residents waited for almost two days amidst rubble, only to die due to lack of heavy equipment to move collapsed concrete structures in Golbasi, Adiyaman.

Informal Emergent Groups Outside the Damaged Region

Interviewees reported that citizens from outside the damaged region sent aid through NGOs, including food and supplies, in a collective effort to assist affected residents. Interviewees also emphasized how welcome the emotional and psychological support they received from civil society organizations was. In Golbasi, interviewees recounted that a theater group from Istanbul organized daily clown performances in tents. Initially intended for children, they said these activities also offered welcome relief to mothers. Religious foundations spontaneously organized craft activities for women and children and offered assistance to surviving families to meet their immediate needs.

Discussion

Alignment of Networks Across Jurisdictional Scales and Organizational Expertise

In large-scale disaster response operations that cross local, regional, national, and international jurisdictions, alignment of operational networks is critical. To achieve this alignment, it is essential to facilitate information exchanged among the actors beforehand. A United Nations representative from the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance confirmed that a communications channel existed between Turkey’s AFAD and international organizations. However, these institutions used different software platforms for communications and data storage, and integrating information from them posed both technical and policy challenges, impeding real-time information exchange. Domestically, AFAD had established crisis centers in Kahramanmaras, Hatay, and Gaziantep provinces with substantial physical storage capacity. Rescue teams from various regions, led by Ankara, were dispatched to the earthquake-stricken area via air, using airports in Gaziantep and Adana. Given the disruptions in telecommunication and electricity infrastructure, coordination was initially achieved using satellite phones, but constrained by the limited availability of the phones.

Gaps in Performance Across Jurisdictions, Organizations, and Disciplinary Expertise

The Kahramanmaras Earthquakes exposed significant shortcomings in performance across various jurisdictions and organizations. Coordination difficulties among different levels of government led to some resources being used in ways that were not needed, while other urgent needs were unmet. Different practices among response teams caused confusion and delays in providing critical assistance and carrying out rescue and recovery operations. Early communication failures increased these gaps, creating problems in the affected areas.

The earthquakes apparently caught disaster-related organizations off guard, despite the region’s known seismic risk. This lack of preparedness revealed a mismatch among different organizations, jurisdictional levels, and areas of expertise. The consequent losses highlight the importance of improved planning and coordination in disaster response efforts.

Conclusions

Implications for Practice and Policy

Key insights for enhancing disaster management follow from this analysis:

Investment in Disaster-Resilient Infrastructure. The visible lack of technical infrastructure in areas affected by the earthquakes underscores the need to invest in building resilient systems. Reliable roads, bridges, and communications are crucial for effective emergency response.

Adaptive Administrative Structures. The persistence of rigid bureaucratic practices, as was evident in response operations, signals the need for adaptive administrative frameworks. Organizational flexibility and open communication channels are crucial to fostering effective disaster mitigation and response.

Local Capacity-Building. The severity of the earthquakes, coupled with the inadequacy of local government resources and training, underscored the limitations of relying on external aid. The losses endured in these events highlight the need to foster local resilience and implement regional capacity-building measures to manage future crises.

Communications and Information Infrastructure. This event documents the vital role of robust communications and information infrastructure. Establishing efficient communication systems is critical for making timely, informed decisions and coordinating actions across regions.

Collaborative Structure. The disaster’s aftermath underscores the value of predefined roles for essential tasks, collaborative teamwork across different disciplines, and engagement among experts from diverse domains. The proactive establishment of frameworks for collaborative action can foster a more comprehensive and unified approach to crisis management.

Limitations

This research was limited in both time and resources. We made two brief trips to visit the earthquake-stricken region and visited four of the eleven affected provinces, including eight districts, but not Elbistan, epicenter of the second earthquake. We conducted our first field study a month after the earthquakes, and did not directly observe search and rescue activities, as the recovery phase was already underway. After the first weeks, most organizations and a significant portion of residents had already left the area. Yet, with assistance from staff in the AFAD central office in Ankara, professional and personal contacts, we engaged with individuals and institutions directly involved in earthquake response. This report builds on the unique experiences of all members of the research team who have closely monitored earthquake events in Turkey spanning two to three decades, enhancing the credibility of the findings.

Dissemination of Results and Future Research Directions

We have disseminated our research at workshops and conferences in the United States, Turkey, and Sweden, including the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI) Conference in San Francisco, California, on April 11, 2023; Natural Hazards Workshop in Broomfield, Colorado, from July 12-13, 2023; Center for Natural Hazards and Disaster Science at Uppsala University, in Sweden, on September 6, 2023; EERI Conference in San Diego, California, on October 27, 2023, and Association of Public Policy and Management Conference in Atlanta, Georgia, from November 9-11, 2023. We have submitted papers to Earthquake Spectra’s special issue on the Kahramanmaras Earthquakes and to the Journal of Design for Resilience in Architecture and Planning, both targeted for publication in 2024.

We note three areas of special interest for future research. First, we identify a key focus on education and the consequences for educational development of children when the school calendar is disrupted, likely affecting their performance in national examinations that shape their future opportunities. Second, we note the central role of business recovery in enabling the damaged communities to regain sufficient stability for residents to return and thrive. Third, we list the continuing need for public health infrastructure and support to traumatized communities.

Acknowledgments

We give warm thanks and sincere appreciation to our colleagues in Turkey who advised us in this study: Ruşen Keleş, Polat Gülkan, Nuray Karanci, Ulvi Saran, Hüseyin Güler, Gunes Ertan, Deniz Yenigun, Mustafa Erdik, and Ali Tekin. Most importantly, we acknowledge the Turkish officials and residents of the cities and towns in the earthquake-affected region who gave their time, thoughts, and candid observations to support this study.

We gratefully acknowledge the Quick Response Program administered by the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado Boulder that enabled this study. The Quick Response Research Award Program is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF Award #1635593). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF or the Natural Hazards Center.

References

-

Erdik, M., Tümsa, M. B. D., Pınar, A., Altunel, E., and Zülfikar, A. C. (2023). A preliminary report on the February 6, 2023 earthquakes in Türkiye, available at https://temblor.net/temblor/preliminary-report-2023-turkey-earthquakes-15027/ (last accessed 27 October 2023). ↩

-

Turkey Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD). (2023a, August 8). 06 February 2023 Pazarcık-Elbistan (Kahramanmaraş) Mw: 7.7 – Mw: 7.6 Earthquakes Report. https://deprem.afad.gov.tr/assets/pdf/Kahramanmaraş%20Depremi%20%20Raporu_02.06.2023.pdf ↩

-

Turkey Strategy and Budget Directorate. (2023, August 7). Turkey Earthquakes Recovery and Reconstruction Assessment. https://www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Turkiye-Recovery-and-Reconstruction-Assessment.pdf ↩

-

Kauffman, S. A. (1993). The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution. Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Glass, R. J., Ames, A. L., Brown, T. J., Maffitt, S. L., Beyeler, W.E., Finley, P.D., Moore, T.W., Linebarger, J.M., Brodsky, N.S., Verzi, S.J., Outkin, A.V., and Zagonel, A.A. (2011). Complex Adaptive Systems of Systems (CASoS) Engineering: Mapping Aspirations to Problem Solutions. Albuquerque: Sandia National Laboratories. June (SAND 2011–3354C). ↩

-

Comfort, L. K. (1999). Shared risk: Complex systems in seismic response. Emerald Group Publishing. ↩

-

Comfort, L. K. (2019). The Dynamics of Risk: Changing technologies and collective action in seismic events. Princeton University Press. ↩

-

Comfort, L. K. (2007). Crisis management in hindsight: Cognition, communication, coordination, and control. Public Administration Review, 67(Special Issue 1), 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00827.x ↩

-

Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. MIT Press. ↩

-

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus, Giroux. ↩

-

Erkan, B., Ertan, G., Yeo, J., & Comfort, L. (2016). Risk, profit, or safety: Sociotechnical systems under stress. Safety Science, 88, 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01118.x ↩

-

Celik, S. & Corbacioglu, S. (2010). Role of information in collective action in dynamic disaster Environments. Disasters, 34(1), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01118.x ↩

-

Celik, S. & Corbacioglu, S. (2016). From linearity to complexity: Emergent characteristics of the 2006 avian influenza response system in Turkey. Safety Science, 90, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2016.01.006 ↩

-

Celik, S. & Corbacioglu, S. (2018). Organizational learning in adapting to dynamic disaster environments in southern Turkey. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 53(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909616677368 ↩

-

Ertan, G., & Çarkoğlu, A. (2022). Cognition, communication, and collective action: Turkey’s response to COVID-19. In L. K. Comfort & M. L. Rhodes (Eds.), Global risk management: The role of collective action in response to COVID-19. Routledge. ↩

-

Balamir, M. (2001). Recent Changes in Turkish Disasters Policy: A Strategical Reorientation? In P. R. Kleindorfer & M. R. Sertel (Eds.), Mitigation and financing of seismic risks: Turkish and International Perspectives, NATO Science Series, 3, 207-234. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ↩

-

Gülkan, P. (2001). Revision of the Turkish development law No. 3194: Governing urban development and land use planning. In P. R. Kleindorfer & M. R. Sertel (Eds.), Mitigation and financing of seismic risks: Turkish and International Perspectives, NATO Science Series, 3, 191–206. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ↩

-

Danielson, M. N., & Keleş, R. (1985). The politics of rapid urbanization: Government and growth in modern Turkey. Holmes & Meier. ↩

-

Keleş, R. (1988). Management of urban growth in Turkey. Turkish Social Science Association. ↩

-

Keleş, R. (2022). Territorial governance and environmental protection: Volume 1: Urban sprawl and sustainable urbanization. Cappadocia University Press. ↩

-

McGrath, E. C. (2015). The Dynamics of Constitutionalism between Democracy and Authoritarianism as a Complex Adaptive System (Publication No. 3735345) [ Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh]. ProQuest LLC. ↩

-

Comfort, L. K., & Rhodes, M. L. (Eds.). (2022). Global Risk Management: The role of collective cognition in response to covid-19. Routledge. ↩

-

Ko, K. (2023). Managing the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea: Policy learning perspectives. Routledge. ↩

-

Yin, R. K. (2016). Case study research design and methods. Sage Publications. ↩

-

Gülkan, H.P. (2018). Natural Hazards Governance in Turkey. In The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science. Subject: Policy and Governance. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.245 ↩

-

Basbug Erkan, B., & Yilmaz, O. (2015). Successes and failures of compulsory risk mitigation: Re-evaluating the Turkish catastrophe insurance pool. Disasters, 39(4), 782–794. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12129 ↩

-

Basbug Erkan, B., Karanci, A. N., Kalaycıoğlu, S., Özden, A. T., Çalışkan, I., & Özakşehir, G. (2015). From emergency response to recovery: Multiple impacts and lessons learned from the 2011 van earthquakes. Earthquake Spectra, 31(1), 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1193/060312eqs205m ↩

-

Lund, B. (2023). The 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquake Sequence: A Seismological Introduction. Swedish National Seismic Network, Uppsala University. ↩

-

Turkish Building Earthquake Regulation, No. 30364, (March 18, 2018). https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2019/07/20190717-6.htm ↩

-

Law on Construction Supervision, No.24461, Law No.4708 (July 13, 2001). https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=4708&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5 ↩

-

Mourenza, A. (2023, February 10). How a ‘piece of paradise’ turned into a grave: the collapse of a luxury building in Antakya. El Pais. https://english.elpais.com/international/2023-02-10/how-a-piece-of-paradise-turned-into-a-grave-the-collapse-of-a-luxury-building-in-antakya.html ↩

-

Nebil, F. S. (2023, July 21). What did our phone operators do during the earthquake? (Part II) Turkcell. T24. https://t24.com.tr/yazarlar/fusun-sarp-nebil/telefon-operatorlerimiz-depremde-ne-yaptilar-ii-turkcell,38916 ↩

-

ReliefWeb. (2023, February 21) Türkiye, Europe Region earthquakes: Emergency appeal n degree MDRTR004 - operational strategy. https://reliefweb.int/report/turkiye/turkiye-europe-region-earthquakes-emergency-appeal-ndeg-mdrtr004-operational-strategy ↩

-

Turkey Disaster and Emergency Management Authority(AFAD). (2023b, August 6). Press Bulletin about the Earthquake in Kahramanmaras – 36. https://reliefweb.int/report/turkiye/afad-press-bulletin-about-earthquake-kahramanmaras-36-entr ↩

Comfort, L., Celik, S., & Basbug Erkan, B., (2024). Communication and Coordination Networks in the 2023 Kahramanmaras Earthquakes (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 365). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/communication-and-coordination-networks-in-the-2023-kahramanmaras-earthquakes