The 2013 Colorado Floods

Reflections on My Personal Experiences with Gilbert F. White

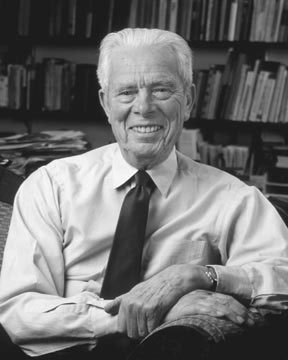

On the occasion of our commemorating the Colorado Front Range Flood that began on September 11, 2013, I was asked to share some stories about my experiences with Gilbert and his passion for floods. My story begins long ago.

I met Gilbert F. White in 1971 a few weeks after I arrived from Los Angeles on the Colorado University campus in Boulder to start graduate school. I had only recently gone through the San Fernando Earthquake, which led me to enroll in a seminar on disasters. A few months later, I was hired as a research assistant on a National Science Foundation project Gilbert was leading. I didn’t know it then, but my life was forever changed, and what I was going to do with it was permanently cast. My prime research duties were to summarize the research of others on a hazard “adjustment” (what Gilbert called them back then), and the adjustment I was assigned was “prediction, forecast, and warnings.” Soon, thereafter, a flood happened in Rapid City, South Dakota and I was asked to consider doing my dissertation research on public response to flood warnings. What’s interesting about this is that at the time, I wasn’t really very interested in floods (I was interested in earthquakes, since I had just gone through one); I wasn’t very interested in public warning response because this topic would mean that I’d have to become a social psychologist (and I wanted to be a different kind of sociologist); and those of you who know me know how the story ends: I’ve spent my lifetime investigating warnings and public response to them.

But this essay isn’t about me. It’s about my relationship with Gilbert. What was happening to me back in graduate school was that I was being shaped, molded, and forged by Gilbert; his fingerprints are still all over me. I’m compelled to share just one story about what being forged by Gilbert looked like.

One day before I started to write the questionnaire I’d use to study public warning response in the Rapid City Flood, I walked into Gilbert’s office to get feedback on my emerging dissertation project. I had taped together a dozen or so pieces of paper, drawn about the same number of columns on the sheets, and explained how the variables I had listed in a column could influence the variables in all the other columns that followed them, but not in the columns that came before them. I called what I had done hypotheses, and I must have had several hundred of them (a half dozen is about all a graduate student should take on in a research project). Gilbert actually held one end of the scroll I’d prepared while I held the other end. We had a hard time viewing the entire document since it was longer that his office was wide. He actually listened to me (with keen intent) talk about the several hundred hypotheses that would become my dissertation. His single comment to me was to gently say (through a broad smile) that he encouraged me to narrow down the number of research questions I was trying to answer. He didn’t tell me what to do. Instead, he pointed me in the right direction. I left his office with the experience of feeling proud of my accomplishment and “bigger” than when I had entered the room. And it is only now that I’m writing this essay that I realize that I left his office that day with the experience of feeling hugged, respected, and even loved; I had just been nurtured by Gilbert F. White.

Many years later, and after I had taken on the directorship of the Natural Hazards Center and while Gilbert still came to work every morning in his basement office of the old house the center was housed in, I learned more about Gilbert. Once a month—and I do mean every month—he and Mary Fran Myers would dash off together to attend a meeting of the Boulder City Council. It was a chance for Gilbert (with Mary Fran at his side) to hug, respect, love, and nurture the Council and point them in the right direction regarding “wise use” of the Boulder floodplain. He talked to more than the City Council about the topic. He would take as much time to talk about the flood hazard to the grammar and high school students who called him to talk about floods as he would to the presidents of nations and the directors of federal agencies that called on him. His logic for taking the time to talk to children was simple: you never know who they might become one day.

An interview with Gilbert White in which he speaks about his role in preparing Boulder for the next great floodThen, on September 11, 2013 a horrific flood started that affected most of Colorado’s Front Range. The first Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) message from the National Weather Service went out to the public shortly after 6:00 P.M. that evening. Gilbert had endowed the Natural Hazards Center to study the next boulder flood. And he had a conversation with me when I was considering the job of center director. It was actually more like an interview than a conversation. I had to promise him that if the next Boulder flood happened while I was director of the center that I’d lead a study of the flood. But he didn’t tell me what to study. In his typical fashion he asked me what I’d study. I thought long and hard before I answered the question. I replied that I’d catalogue every death the happened in the city limits and do a historical account of the decisions made by the City Council that may have been the root cause of the people who died. Gilbert smiled. We both assumed that the next Boulder flood would be a flash flood with walls of water coming down the canyons, that it would be catastrophic, and that many lives would be lost. But that’s not what happened. I don’t mean to diminish the importance of the lives that were lost in the recent flood, nor the untold human suffering that it caused and continues to impose on victims, but what actually happened was that most things went right (not wrong). Here’s one example of what went right and how I link it back to Gilbert.

Evacuation ordered: Mouth of Boulder Canyon to Broadway, Pearl to Marine GO TO HIGHER GROUND immediately #boulderflood

— Boulder OEM (@BoulderOEM) September 13, 2013While evacuating DO NOT cross Boulder Creek #boulderflood

— Boulder OEM (@BoulderOEM) September 13, 2013The key applied lesson I learned in my dissertation research on the Rapid City Flood was that flood warnings (perhaps warnings in general) must be very specific about the area of impact vs. safe areas. The Weather Service warnings that went out in Rapid City told people who lived “close to the creek” to evacuate. But “close” meant different things to different people and some people who lived on the creek’s edge went across the street thinking they’d be safe. They weren’t. Then I read the warning messages that Boulder Emergency Management issued about the flood. They said something like this: if you’re close to Boulder Creek on the north side, evacuate north of Pearl Street, and do not cross the creek. This is exactly the sort of specificity of information that warnings need to contain. People in Rapid City died to teach us that lesson. Some people in the recent Boulder flood may have lived because that lesson was applied. I actually don’t know why Boulder Emergency Management worded their warning messages so well (and why so many diverse communication channels were use to disseminate them—another social science lesson about how to do warnings best), but I’m left wondering if Gilbert had shared those ideas with the city on one or more of his trips to talk with people in the city with Mary Fran at his side. My tale is almost over, but there’s one more piece to this story. It actually provides evidence for the adage “What goes around, comes around.” Guess who’s studying public response in Boulder to the recent flood warnings. I hope readers forgive me, but I just can’t help word my last comments as if I’m talking to Gilbert. Here goes.

Gilbert, I’m supposed to be retired, but I’m still doing research on public response to warnings. The nation has a new Emergency Alert System. It’s called the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS). It has a lot of parts including things they call the Common Alerting Protocol, instructional fields, Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEAs), and lots more. The most exciting part of the system is that they can deliver a warning message (which everyone now calls alerts not warnings) to people at risk on their cell phones (pretty much whether they want them or not). We call them “text messages.” But they can’t be more than 90 characters long. But no one every tested the messages to see if they work from a public response viewpoint. I convinced the Department of Homeland Security (with National Telecommunications and Information Agency money) to do some research on the topic. I’m working with other researchers (all younger than me) to discern what an optimized WEA message might be like from a public perception and response viewpoint. The research has three phases. First, we read and summarized everything there is on the topic and had a meeting in Washington, D.C. to get feedback from the agencies—just like you taught me—to increase the odds of our findings being used. Second, we conducted a series of Internet and laboratory experiments to answer questions that no one has ever asked before, for example, what’s the best order for the contents of a message, does the length of a message matter, and more; then we checked out the experimental findings in focus groups and think-out-loud interviews. Last, we’ve exported all of the findings into the real world to see if they hold up outside the prior artificial research settings. We went on a hunt for just the right disaster event to study, but we couldn’t find one. Then a flood happened in Colorado and we’re just about to study it. We’ll be doing interviews on two statistically representative samples of residents of the City of Boulder: (1) the general population of the city, and (2) an oversample of people who had cell phones and got WEA messages. This isn’t the study of the Boulder flood I thought I might do the day you interviewed me for the center director job. It might actually end up saving more lives. And here’ the good part: all the younger colleagues I’m working with are really excited about studying warnings on their own after the project is over. I may have put my fingerprints all over them like yours are on me. And wait, there’s more to get excited about. The agencies have already picked up on some of our findings and are using them to makes some changes in the WEA system.

--Dennis Mileti, former director of the Natural Hazards Center