An Empirical Investigation of the Material Convergence Problem

Publication Date: 2015

Abstract

Material convergence represents the flow of supplies, donations, and equipment that travels to an area in the aftermath of a disaster. Unfortunately, unsolicited or in-kind donations can disrupt the ability of responders to effectively manage items that arrive, thereby impeding the distribution of necessary items to those affected by the disaster. With this issue in mind, therefore, a series of interviews was conducted in the aftermath of the September 2013 flooding in Colorado in order to determine the extent and impact of material convergence on the relief efforts for this particular disaster event. This case study found that messaging focused on encouraging financial donations and proper types of material donations, together with effective donations management, was able to reduce the negative impacts of material convergence.

Introduction

Material convergence represents the flow of supplies, donations (solicited and unsolicited), and equipment that travels to an area in the aftermath of a disaster (Fritz and Mathewson, 1957)1. The flow of solicited donations and other resources requisitioned directly by a government agency or non-government relief organization for the response to a disaster can be managed effectively, while unsolicited or in-kind donations can disrupt the ability of responders to effectively manage items that arrive, thereby impeding the distribution of items to those affected by the disaster.

The impact of unsolicited donations on the relief efforts is due to numerous factors, such as the quality or appropriateness of the items, and the additional sorting and inventorying requirements posed by items that arrive from unknown sources at irregular intervals. The Pan American Health Organization recognizes that unsolicited donations can take several forms and developed the following classification: high-priority (HP), those required for immediate distribution and consumption; low-priority (LP), those that are not immediately required but may be useful in later stages of recovery; and non-priority (NP), those that should not have been sent to disaster area at all (Pan American Health Organization, 2001)2. Interviews with responders from several past disasters indicated that NP goods frequently have exceeded 50% of the unsolicited cargo that arrives.

With this issue in mind, the investigators of this project conducted a series of interviews in the aftermath of the September 2013 flooding along the Front Range in Colorado, in order to determine the extent and impact of material convergence on the relief efforts for this particular disaster event, and to identify the actions taken by relief organizations to discourage the donation of LP and NP items. This report discusses our findings.

Background

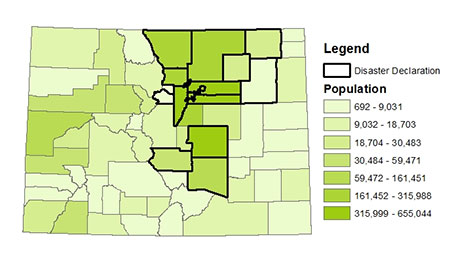

On September 10th, 2013 rain began falling on much of the Front Range in Colorado, intensifying on the 11th and 12th before finally receding by the 15th. During this period double-digit inches of rainfall was reported in most of the Front Range, with the city of Boulder recording more than 21 inches (Coffman, 2013)3. During the most intense periods over 12,000 people were evacuated, while at least 1,000 people were isolated in Larimer County alone (Coffman, 2013). Approximately 4,500 square miles, or 2.88 million acres, were impacted by the flooding (Dreier & Neary, 2013)[^(Dreier & Neary, 2013)]. On September 12th, President Barack Obama signed an emergency declaration for Boulder, El Paso, and Larimer counties (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2013a)4, with an additional twelve counties added to the emergency declaration on September 15th (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2013b)5 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Map of Region

The flooding caused hundreds of road closures, particularly in the northern portion of the Front Range. This lead to several towns such as Estes Park (CBS4, 2013)6, Lyons (Banda, 2013)7, and Milliken (Nguyen, 2013)8 being isolated, as well as limiting access to many other towns in the region and generally making travel more difficult for residents needing to evacuate and organizations looking to provide assistance. In some instances, helicopter airlifts were necessary to facilitate evacuations (Slevin & Paulson, 2013)[^(Slevin & Paulson, 2013)]. At the peak of the disaster, 1,254 people were unaccounted for (Stoller, 2013)9. Fortunately, most of these people were found and there were only ten deaths attributed to the flooding, while 1,882 structures were destroyed, and over 16,000 others were damaged (Colorado Recovery Office, 2014)10. The estimated damages are nearly $2 billion (Isidore, 2013)11. The scale of the event was comparable to several recent hurricanes.

During the response efforts, numerous shelters, disaster assistance centers (DACs), and disaster recovery centers (DRCs) were opened. In addition, a flood relief distribution center was established in Loveland, located in Larimer County,which provided clothing, linens, food, kitchen supplies, tools, hygiene products, pet supplies, and more. This was the main location for distribution of such items in the northern region of the state, as other heavily impacted counties, such as Weld, chose not to open facilities. However, a smaller distribution operation was set up by Boulder County at the DRC location in the city of Boulder. There were no distribution centers for supplies established in the southern portion of the state.

Methodology

In the aftermath of the flooding, the research team conducted interviews with fourteen people involved in the relief and recovery efforts (Table 1). The purpose of these interviews was to assess the effectiveness of the relief efforts and to determine the extent of the impacts that material convergence had on this particular disaster event. The interviewees included representatives from non-profit and religious organizations, as well as from county, state, and federal governments. Many of these interviews were conducted in-person and recorded with consent of the interviewee, while other interviews were conducted via phone. In addition to the interviews, a member of the research team toured the distribution center in Loveland and spoke informally with several volunteers, as well as briefly touring the warehouse facility that served the Boulder distribution center (although the distribution center itself was not toured).

| Interviewee | Title | Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Sally Broomfield | Disaster Program Manager | Red Cross – Pikes Peak Chapter |

| Elizabeth DiPaolo | Mass Care Specialist | FEMA Region VIII |

| Donna Hasman-Black | Volunteer | Rocky Mountain Evangelical Free Church |

| Betty Kaan | Logistics Specialist | Red Cross – Northern Colorado Chapter |

| Cathy Kissner | Rocky Mountain Conference Disaster Response Coordinator | Adventist Community Services |

| Robyn Knappe | State Voluntary Agency Liaison | Colorado Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management |

| Merrie Leach | Emergency Management Coordinator | Weld County Office of Emergency Management |

| Sandi Meier | Manager, Special Projects | United Way of Weld County |

| Erin Mounsey | Executive Director | Red Cross – Northern Colorado Chapter |

| Jaici Murcia | Disaster Officer | Red Cross – Colorado & Wyoming Region |

| Jennifer Poitras | Coordinator | Colorado Donation/Volunteer Coordination Team |

| Britta Robinson | Associate Director | A Precious Child, Inc. |

| Mark Smith | Lead Specialist – Logistics | Red Cross – Colorado & Wyoming Region |

| June Spalding | Volunteer | Adventist Community Services |

Table 1: List of Interviewees

Discussion and analysis

Based on the results of the interviews, it appears that the relief efforts in the wake of the September 2013 flooding in Colorado went quite smoothly compared to reports from previously published research. This does not mean that there were no problems encountered, but for the majority of the impacted region material convergence was not an impediment to the effective distribution of supplies to those in need of assistance.

In the immediate aftermath of any disaster, the focus is on providing shelter, food, water, and overall safety for people that have been evacuated. For the flooding, the majority of this work in Colorado was handled by the American Red Cross, though in some instances this work was managed in part by other organizations, such as the YMCA in Boulder. As the Red Cross is not traditionally a “taker of stuff” (Murcia), the vast majority of their physical in-kind donations are solicited from corporate partners and other large donors. Most of these donations were from established relationships and represented 10% of the cost of the relief operation. The Red Cross logs only those donations that are utilized, and there “was probably another 10% that we could not take” (Murcia) due to incompatibility, lack of need, of issues of quantity.

An organization that was widely credited with performing a difficult function with great efficiency was Adventist Community Services (ACS) group, part of the Rocky Mountain Conference of Seventh-Day Adventists. Cathy Kissner, the Director of Community Services and Disaster Relief for ACS in the region, was mentioned by several interviewees as excelling at running distribution centers for material donations, and all of the volunteers with ACS were lauded for their work. ACS has performed this function in previous disasters, including the High Park Fire of 2012. Given this historic involvement, ACS was the go-to organization when the decision was made by Larimer County to host a distribution site. A location was selected in Loveland based on size, availability, and accessibility and was open unofficially on September 15th and was operating officially on September 18th.

The Loveland location held open collections for two weeks wherein donors could drop off bags or boxes of items, though they were encouraged to donate only items that matched explicitly stated needs. After those two weeks, donations were limited to only those items being requested at that time. By limiting the time for open collection and having a list of needs available on websites such as HelpColoradoNow, Kissner estimates that 80% of items received were appropriate and usable. This figure was the same estimate solicited from several volunteers at the Loveland facility as well. Given that previous research has shown that non-priority flows in the aftermath of disaster can exceed 50%, this figure represents a successful effort by ACS and the Colorado Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (COVOAD) to control the message and influence donor behavior. According to Kissner, ACS has become more proficient over the years and this figure is an improvement over past efforts. Approximately 15% of items were unneeded or of low-quality and were separated and given to other charitable organizations, while 5% of items donated were unacceptable quality and were disposed of. ACS utilizes a 1-2-3 step approach to separating items, and the rule of thumb is only keep things that you would be comfortable asking a family member to wear or use. Although the Loveland site was the official collection and distribution center for Larimer County, this became the unofficial site for several other northern Colorado counties, such as Morgan and Weld, which chose not to open centers in their jurisdictions.

Boulder County, however, chose to open a separate distribution center, which was operated by A Precious Child, an organization based in Broomfield, a consolidated city-county, located between Denver and Boulder. The organization serves disadvantaged and displaced children that are facing difficult circumstances, but these are generally not as critical or time-sensitive as the flooding events. A Precious Child has the infrastructure in place to accept and distribute material donations and they offered their services because “this is what we do” (Robinson), though this was of a larger, more general scope than their usual focus on children. They began working with FEMA in Boulder distributing shopping vouchers for their facility in Broomfield so that families could receive some of the essentials they needed, such as clothing and bedding. FEMA started a small resource donation and distribution center in Boulder, which A Precious Child took over in early October and scaled up utilizing their existing warehouse and volunteers to make this happen. During this period of time, the organization tapped into its regular donor base via e-mail and soliciting material donations beyond their regular needs and to find volunteers. A Precious Child experienced some degree of unnecessary items showing up as donations, but the organization estimates that 80-85% of the material donations were high-quality and usable. This is particularly noteworthy as they stated that this percentage is higher than they see during the course of normal operations.

Though large in-kind donations, often from corporations, can pose a problem when they are inappropriate, the problem of material convergence can often stem from the smaller donations that come from individuals or smaller organizations. Several interviewees that have been involved in disaster relief for a many years mentioned issues of material convergence occurring for historical events, including those that happened outside of the region. For example, during Hurricane Katrina, the Red Cross would see “piles of bags of stuff” (Mounsey) at any location with a Red Cross sign, including facilities that were not even in use and near any vehicle. The problem was described as “once the first bag appears, then more and more show up. It just multiplies; it’s like Gremlins or something” (Mounsey). During several of the recent wildfires, there were also reports of spontaneous donations showing up at fire departments and often blocking the garage doors. During the September floods, however, every respondent commented that these types of donations were much smaller than previously seen.

One of the explanations given for this decrease in spontaneous donations being made at improper locations was the effectiveness of messaging. The focus on messaging in Colorado is very strong and was widely credited as a reason that unnecessary or improper material donations were much smaller than have been seen in previous disasters, even compared to the wildfires in the past several years. COVOAD has been working on coordinating efforts in the state and one aspect of that coordination is a message that has been standardized and is ready to go in the immediate aftermath of a disaster (Knappe, Leach, Murcia). That message is that “cash is king” and the focus is on encouraging monetary donations (Knappe, Mounsey, Murcia). The approach is “consistency, early, often” (Murcia) as a means of reinforcing this message in the minds of the public. The use of social media was also recognized as an important factor in controlling the messaging (Leach, Kaan). For the Red Cross, the text-to-help number that generates an automatic $10 donation was a factor mentioned in the ability to increase the focus on financial donations over material donations (Mounsey, Murcia). The ease with which donors can help via a text provides people with an outlet to get involved without causing a strain on resources through improper donations. It also provides the relief organizations with money that can be targeted towards specific needs, and that money is able to go further and be more effective than an equivalent physical donation (Murcia).

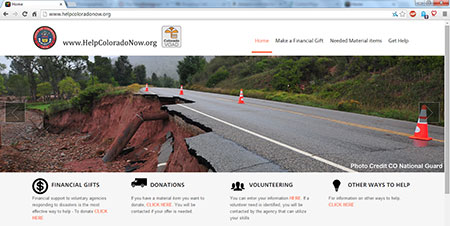

A key aspect of the messaging in the state was the development of the HelpColoradoNow website, which works with .com, .org, and .net domains (Figure 2). HelpColoradoNow is a project of COVOAD in partnership with the Donation and Volunteer Coordination Team (DVCT) and the Colorado Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management (DHSEM). “Based on previous experience, the public want to help, but they don’t always know how to help. The idea was to create one spot where the public can go to get information about if they want to donate, want to volunteer or want to give a financial contribution” (Poitras). HelpColoradoNow was explicitly mentioned by almost every interviewee as a significant factor in improving messaging within the state, increasing the focus on financial contribution, and easing the burden from spontaneous material and volunteer donations at response and relief sites.

Figure 2: Screenshot of HelpColoradoNow website

Donations through HelpColoradoNow are managed through Aidmatrix. The Aidmatrix software platform was mentioned by a number of interviewees as the best option for establishing new relationships for in-kind donations and matching needs with existing offers. For large donations being made to the Loveland center, for example, the use of Aidmatrix was credited with easing the burdens on resources while providing better matches between needs and offers (Kissner, Poitras). The benefits of using Aidmatrix were apparent from the interviews: the ability to push needs and pull resources (Kissner), the use of alerts for new offers (Knappe), and the ease with which state-level coordinators could help facilitate transactions (Poitras). Even organizations that were new to relief efforts, such as A Precious Child, were able to pick-up on Aidmatrix and benefit from this tool. As Aidmatrix requires the match of needs and offers, this eliminates corporations and other large donors from making large donations of inappropriate or unnecessary items in the midst of the relief efforts, allowing organizations to stay focused on the essential operations, as well as allowing for offers of necessary items to be pulled only at the appropriate time. This keeps these offers in a virtual space rather than interfering with on-the-ground activities (Knappe).

Though post-flooding material convergence was reported to be much less of a problem than seen historically, there were still instances of people wanting to donate and going about this incorrectly. Although the 80% acceptable donation figures are high compared to previous research, there were still donations of non-beneficial items (tchotchkes, broken equipment, etc) being made. Interviewees also mentioned that people would show up to offices of organizations with bags of items, or that bags of items would be left outside overnight. In these instances, the organizations attempted to explain the proper channels for these donations, either directly to the distribution centers if they were accepting items, or, failing that, encouraging donation of these items to charitable organizations that specialize in taking “stuff” or holding yard sales and then donating that money to relief efforts. In instances where items were left overnight or people were adamant about dropping off these donations in the improper locations, interviewees mentioned that they could take these items to the appropriate locations to ensure that they were used effectively. Another instance of improper, although well-intentioned, donations that was mentioned by several interviewees was people that showed up to shelters with cooked meals, which cannot be served to victims due to health regulations. Though messaging was used effectively in Colorado, there were still occurrences of improper donations, showing that there is still room for improvement.

In terms of large donations, not all items came from corporations. Robinson mentioned two pallets of clothing that were gathered during a clothing drive organized by two middle-school aged children in Florida. Other large donations by individuals, church groups, and other non-profit organizations were reported in addition to the corporate donations. Though these large donations were generally coordinated in advance so that the relief organizations would be aware of their arrival, in some instances this did not happen. In late November the Red Cross in Fort Collins received a shipment of comfort kits that had been created by a church group in another state. Each kit was a plastic bag filled with hygiene and other small items, and several dozen boxes filled with these kits appeared at the office suddenly. These kits would have been most appropriate in the immediate aftermath as people were residents in shelters or other short-term housing, but in late November they were not as pressing a need. Fortunately, some of the items in the kits were still in high demand so several boxes of the kits were taken over periods of time to the center in Loveland where they could be disassembled and the most necessary components could be given to victims.

Summary and conclusions

The September 2013 flooding response and relief efforts in Colorado went relatively smoothly, and there were substantially lower levels of material convergence that posed problems. In fact, no one referred to this as the “second disaster” or a major issue that impeded response efforts, even though this had occurred in the past. Those practices and methods that worked well, along with recommendations for improvements given by interviewees, can be used to provide a foundation on which other response and relief efforts can be based to enable better responses to future disasters in Colorado and beyond.

The strength of COVOAD was consistently mentioned by interviewees as a primary reason for the success of the response and relief efforts. COVOAD, as well as the state, county, and local governments, have worked over the past few years to improve their disaster relief plans. Nearly every interviewee discussed the role of planning in effective response. Most interviewees recognized that planning will continue to be a focal point after this disaster. Lessons learned from these events will be utilized in the next generation of plans.

Messaging was also largely credited as being successful, due in a large part to the use of HelpColoradoNow. This provided one location for potential donors and volunteers to go to. Rather than having organizations competing for mentions in the media, people were directed to this one site which provided them with the most crucial information, including links at which they could make financial donations, a list of specific material items needed, and information about volunteering. This reinforced the consistency of the message by having all information in one location, rather than having potentially different information at a variety of sources. Internal messaging within organizations and word-of-mouth were often credited with being important as well. Also, having pre-planned messages, whether focusing on the “cash is king” idea or on specific needs, or some combination of both, was mentioned as important to controlling the message.

Aidmatrix was also discussed frequently as a reason for the success of materials management in the post-flooding response. Not only was Aidmatrix used on HelpColoradoNow to control the list of acceptable or needed items for donation, but the ability of Aidmatrix to screen offers was very important to reducing spontaneous donations showing up at the site, particularly those in large quantities, when they were unneeded.

References

-

Fritz, C. E., & Mathewson, J. H. (1957). Convergence Behavior in Disasters: A Problem in Social Control: a Special Report Prepared for the Committee on Disaster Studies. National Academy of Sciences National Research Council. ↩

-

Pan American Health Organization (2001). Humanitarian Supply Management and Logistics in the Health Sector. Washington, DC. ↩

-

Coffman, K. (2013) Colorado evacuations continue as flood crest moves downstream. Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/09/17/us-usa-colorado-flooding-idUSBRE98B0KM20130917 . Retrieved May 28, 2014. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2013a) President Obama Signs Colorado Emergency Declaration. Release Number: HQ-13-098. http://www.fema.gov/news-release/2013/09/12/president-obama-signs-colorado-emergency-declaration . Retrieved May 28, 2014. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2013b) 12 Counties Added to Colorado Disaster Declaration for Emergency Assistance. Release Number: NR-001. http://www.fema.gov/news-release/2013/09/15/12-counties-added-colorado-disaster-declaration-emergency-assistance . Retrieved May 28, 2014. ↩

-

CBS4. (2013) Estes Park Just One of Many Communities Isolated By Flooding. CBS4, Denver. http://denver.cbslocal.com/2013/09/14/estes-park-just-one-of-many-communities-isolated-by-flooding/ . Retrieved May 28, 2014. ↩

-

Banda, P.S. (2013) Colorado Flooding Cuts Off Mountain Town, Kills 3. Associated Press. http://bigstory.ap.org/article/flash-flooding-hits-parts-boulder-county . Retrieved May 28, 2014. ↩

-

Nguyen, K. (2013) Weld County flood devastation; Evans, Greeley, Milliken under water as South Platte River overflows. ABC7, Denver. http://www.thedenverchannel.com/news/local-news/flood-devastation-in-weld-county . Retrieved May 28, 2014. ↩

-

Stoller, G. (2013) More Than 1,000 Unaccounted For In Deadly Colo. Floods. USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/story/weather/2013/09/15/boulder-colorado-floods-larimer/2815667/ . Retrieved May 28, 2014. ↩

-

Colorado Recovery Office. (2014) Colorado Flooding – Six Months Later. State of Colorado Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. http://www.coemergency.com/2014/03/colorado-flooding-six-months-later.html . Retrieved May 28, 2014 ↩

-

Isidore, C. (2013) Colorado Floods: Costly and Often Uninsured. CNN Money. http://www.usatoday.com/story/weather/2013/09/15/boulder-colorado-floods-larimer/2815667/ . Retrieved May 28, 2014. ↩

Arnette, A. N. & Zobel, C. (2015). An Empirical Investigation of the Material Convergence Problem (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 253). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/an-empirical-investigation-of-the-material-convergence-problem