Evacuation Decision-Making Post-Vaccine

Implications of Compound Hazards in U.S. Territories

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

The purpose of this study, conducted in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, is to determine how risk perceptions related to hurricane evacuations may have shifted when vaccines became available during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, the study explores the following three topics: (1) whether vaccination status affects hurricane evacuation plans; (2) whether the availability of vaccines affects residents’ hurricane evacuation plans compared to the pre-vaccine era of COVID-19; and (3) whether the perception of other people's vaccination status affects evacuation plans. An online survey was disseminated to the public. When asked whether the vaccination status of respondents would affect their decision to evacuate for a hurricane, an overwhelming majority (72.6%) replied “no.” However, vaccination status and deciding whether to evacuate are significantly associated. Interestingly, those who are unvaccinated responded that they are more likely to evacuate during a storm than those who are vaccinated. The likelihood of respondents utilizing a shelter during the 2021 hurricane season aligned with the likelihood prior to vaccine availability, as nearly 40% of respondents "definitely" would not have evacuated to a shelter in this post-vaccine era. Respondents generally believed that more people on their island were unvaccinated than those that were vaccinated against COVID-19, perhaps leading to their reluctance to use a shelter. Government officials need to develop and communicate clear information regarding evacuation orders for certain municipalities that may be more impacted than others based upon the trajectory of the storm, social determinants of health, and other factors like living in a flood zone or in vulnerable housing structures.

Introduction

While Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands are vulnerable to multiple natural hazards—including earthquakes, tsunamis, wildfires, and drought—hurricanes pose the greatest threat to the region (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA], 20221). The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound effect on hurricane evacuation decisions, as seen in previous evacuation research on Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Collins et al. (2021a2, 2022a3) found that individuals who would have previously evacuated to a shelter before the pandemic would choose not to during the pandemic, reflecting that public shelter usage has the potential to decrease when the decision is coupled with COVID-19 threats. Individuals were also shown to have a negative perception of public shelter options, with approximately half of the respondents having little faith in shelters' ability to maintain social distancing and implement other preventative measures. More than half of the sample stated that they would "definitely" shelter-in-place to minimize exposure to large groups in the shelter, and 75.5% of the sample thought that the risks of being in a shelter were higher than those that they would have to endure if they were to stay home during a hurricane (Collins et al., 2021a, 2022a). Since this initial study, vaccines are now widely available and there are fewer COVID-19 related hospitalizations. It is the purpose of this study to determine how risk perceptions may have shifted under these new conditions.

Literature Review

Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands Region

More than 15% of all Atlantic hurricanes in any given year impact the Caribbean Antilles, the region where Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands are located (Jury et al., 20194). According to the National Hurricane Center (20225), Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands average 1.1–1.94 named tropical cyclones per year, leading to disaster-induced displacement or evacuation orders for these small, isolated islands. Along with high winds, these storms often bring storm surge, intense rains, flooding, and landslides to the islands.

In 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria prompted significant evacuations in the region, with shelters housing 10,692 people in Puerto Rico and 558 people in the U.S. Virgin Islands (Pan American Health Organization, 20176). The aftermath of these storms included major disruptions to health care stemming from damaged hospital infrastructure. Older, chronically ill patients were more at risk due to the collapse of their social networks and support systems (Chowdhury et al., 20197). Most of the region experienced a complete loss of electricity and unreliable potable water service that lasted for months due to weak and outdated utilities. The topography and abundant tropical moisture of the regions introduce a significant landslide threat in addition to the other risks associated with hurricanes, complicating any evacuation and recovery processes (Wang et al., 20148).

COVID-19 in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands

The spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the subsequent emergence and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine creates an additional dimension of hurricane vulnerability. The region was heavily affected by COVID-19, with more than 100,000 infections and 2,000 deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 20219). During the time that the survey was being distributed (March 2021–May 2021), infection rates in Puerto Rico ranged between 0.03–0.29% and 0.02–0.04% in the U.S. Virgin Islands (Table 1). There was a particularly high peak in April 2021, followed by an increase in hospitalizations and deaths. Overall, positivity rates and COVID-19 related deaths in Puerto Rico were generally greater than those in the U.S. Virgin Islands (CDC, 2021). As of June 2023, Puerto Rico has seen a total of 1,252,713 cases of COVID-19 with 7,846,764 vaccine doses administered, and the U.S. Virgin Islands have reported 25,182 confirmed COVID-19 cases (vaccine statistics not found) (World Health Organization, n.d[^WHO, n.d.]).

Table 1. COVID-19 and Vaccination Statistics in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands

| Total Population Estimate | July 2021 | ||

| COVID-19 Cases | March 2021 | ||

| April 2021 | |||

| May 2021 | |||

| COVID-19 Positivity Rate (per 1,000 people) | March 2021 | ||

| April 2021 | |||

| May 2021 | |||

| COVID-19 Deaths | March 2021 | ||

| April 2021 | |||

| May 2021 | |||

| People Vaccinated (1st Dose) | March 2021 | ||

| April 2021 | |||

| May 2021 | |||

| People Vaccinated (2nd Dose) | March 2021 | ||

| April 2021 | |||

| May 2021 |

As vaccines moved toward authorization by late 2020, the Puerto Rico Department of Health began a vaccination campaign for its residents. During the time of the survey, approximately 11–33% of the total population of Puerto Rico was vaccinated with their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, while 6–24% was fully (two dose sequence) vaccinated. The U.S. Virgin Islands population had a slightly higher vaccination rate with 15–39% completing their first dose, and 7–30% fully vaccinated (Table 1).

Social Vulnerability and Hurricane Evacuation Decision-Making

Access to resources, limited representation and social capital, cultural beliefs and customs, the presence of physical limitations, and the built environment are various determinants of social vulnerability to natural hazards (Cutter et al., 200310; Tierney et al., 200111). Several studies have found that income, prior experiences, perceived susceptibility and severity, inequities, age, and the presence of a chronic condition are significant indicators of preparedness for hurricane evacuations (Aldrich & Benson, 200812; Brown et al., 201213; Donner & Lavariega-Montforti, 201814; Elder et al., 200715; Koloushani et al., 2022[^Koloushani]; Sohn & Kotval-Karamchandani, 202316). Previous experiences with evacuation and financial loss can increase evacuation intentions, while emotional impacts can either increase or decrease these intentions by impacting fear and anxiety as well as an individual's self-efficacy (Demuth et al., 201617). Lazo et al. (201518) found that evacuation orders from public officials have a greater impact on evacuation intentions than hurricane watches and warnings provided by forecasts. Many people also rely on their social infrastructure for information and decision-making. As demonstrated from research during Hurricane Katrina, the strength of social connections impacted evacuation decisions among minority communities by impacting access to transportation, money, shelter, and more (Eisenman et al., 200719).

[Koloushani]: Koloushani, M., Ghorbanzadeh, M., Gray, N., Raphael, P., Ozguven, E. E., Charness, N., Yazici, A., Boot, W. R., Eby, D. W., & Molnar, L. J. (2022). Older adults’ concerns regarding hurricane-induced evacuations during COVID-19: Questionnaire findings. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 15, 100676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2022.100676

Disease Transmission and Hurricane Evacuation Decision-Making

The conflicting needs to social distance to limit the spread of COVID-19 and congregate in safe locations during a hurricane exacerbate preexisting vulnerabilities and further complicate the role of emergency managers in designing hurricane evacuation strategies (Campbell et al., 202120; Ford et al., 202221; Pei et al., 202022; Phillips et al., 202023; Shultz et al., 202024). They must rapidly assess the hydrological and wind threats presented by the incoming storm while also monitoring and addressing any health needs of residents in public shelters (Demuth et al., 201225; Schnall et al., 201926). Whytlaw et al. (202127) note that vulnerabilities caused by preexisting health conditions and socio-economic disparities are of greater concern to emergency planners.

Studies conducted since the pandemic have found a negative perception of public shelters, meaning people are less willing to risk contracting COVID-19 in a shelter than enduring a hurricane in place (Collins et al., 2021b28, 2022b29; Zhao et al., 202230). Several studies describe how older individuals are even more hesitant to evacuate during the COVID-19 era due to their increased vulnerability to the disease (Botzen et al., 202231). When older individuals do evacuate, especially those of lower income and who live alone, they are more likely to need additional assistance in evacuating and require shelters that cater more to their needs (Koloushani et al., 2022).

Hurricane Evacuation Decision-Making in the U.S. Territories

Studies examining evacuation decision-making during COVID-19 in the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands are limited. The populations in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands differ from those examined in existing research in the mainland United States, and since different populations respond to information differently and have varying circumstances, it is important to consider these differences when developing communication and preparation strategies ahead of natural hazards (Morss et al., 201632). Preparing evacuation routes is more complicated for islands like those in the Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, as mass evacuations from coastal areas to safer inland regions are not feasible on smaller islands and limited for larger islands (Cox et al., 201933; Shultz et al., 201934). Emergency managers must also consider people fleeing the island itself rather than evacuating inland (Acosta et al., 202035). For example, after Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico experienced an estimated population loss of 475,779 people while 123,000 permanently relocated to the United States after Hurricane Fiona (Acosta et al., 2020; U.S. Census Bureau, 2022a36).

Of the few studies conducted in this region, Collins et al. (2022a) found that half of the study participants felt vulnerable to COVID-19 and three-quarters of respondents believed the risks of COVID-19 in public shelters outweighed those of enduring a hurricane without evacuating. Additionally, Puerto Ricans who focused more on evacuation expenses and the probability of spreading COVID-19 in their community were less likely to evacuate despite evacuation orders. On the other hand, those who had previous hurricane evacuation experience who had concerns about the storm impacts and considered the probability of infecting their friends and family (rather than society) were more likely to evacuate despite the threat of COVID-19 (Meng et al., 202237). With the rapidly changing COVID-19 environment and the availability of vaccines, residents in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands may have different perspectives on their level of risk during the hurricane season.

Research Questions

The purpose of the research conducted in the Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands is to further investigate individuals’ risk perceptions and evacuation choices during the COVID-19 pandemic, addressing the added impact of the COVID-19 vaccine on public health perceptions. In particular, the study explores the three following topics:

- Whether vaccination status affects hurricane evacuation plans;

- Whether the availability of vaccines affects the hurricane evacuation plans of residents compared to the pre-vaccine era of COVID-19; and

- Whether perceptions of other people’s vaccination status affect evacuation plans.

Research Design

During the 2020 hurricane season, an initial online survey (in English, Spanish, and French Creole) of 70 questions was disseminated to residents of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, with 457 people responding from more than 120 zip codes. This initial research conducted pre-vaccine availability by Collins et al. (2022a) informed the development of the post-vaccine hurricane survey instrument. Several meetings involving the research team and community stakeholders allowed for opportunities to provide updates to the original survey. A strong emphasis was placed on collecting valuable information for practitioners who planned for and responded to the needs of residents in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands during a hurricane and supported the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. A draft survey instrument was then circulated for comment among emergency management, public health, geoscience, and communications subject matter experts.

Survey instruments developed by the research team were available in English or Spanish. Prior to dissemination, survey instruments were pilot tested by native Spanish and English speakers. This was done to test the equivalence of translated instruments and determine a consensus on alternative wording if necessary. In general, the questions performed well regarding perceived clarity, the accuracy of the translation, the structure of the questions, and the technology used, with only minor changes needing to be made to the survey instrument. After final revisions, the survey instruments were submitted to the Ponce Health Sciences Human Research Protection Program, exempted by the Institutional Review Board.

Study Site, Sampling Strategy, and Distribution

The survey was disseminated online through Qualtrics within Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands between March 2021 and May 2021. The study sample represented more than 128 zip codes spread across three primary islands in the U.S. Virgin Islands (St. Croix, St. John, and St. Thomas) and 71 municipalities in Puerto Rico. All residents of Puerto Rico (21 years or older) and the U.S. Virgin Islands (18 years or older) were included in the target sample criteria, as the whole region is affected by hurricanes and is at risk for a hurricane evacuation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The samples were obtained through convenience sampling utilizing an extensive network of personal and professional connections in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, who further disseminated the digital link to their networks. Additionally, connections were made by these professional contacts to distribute to trusted community leaders, local news stations, and social media to catch a wide variety of respondents. Targeted Facebook advertisements provided more exposure in underrepresented areas. Respondents were not compensated for their participation in the study.

Sample Demographics

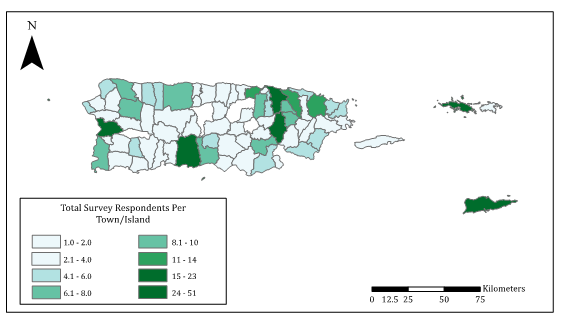

In total, 547 unique survey respondents participated in the study, with a completion rate of 71.7% (n = 392). Each survey question was used for analysis, but the number of respondents may vary due to missing responses. Most respondents who provided their location (82%) were from Puerto Rico, with the remaining (18%) from the U.S. Virgin Islands, as represented in Figure 1. Of those, most respondents were from St. Croix and St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Mayagüez, Ponce, Caguas, and San Juan in Puerto Rico. Most respondents (78.2%) completed the survey in Spanish, many of whom (64.2%) considered English their second language.

Figure 1. Location of Survey Respondents per Puerto Rico Municipality and Island in the U.S. Virgin Islands

The median birth year of respondents was 1974, with the oldest born in 1926 and the youngest born in 2000. The sample consisted of mostly female respondents (71.8%) which is disproportionately higher than the rate (51.3%) across the islands (U.S. Census, 2022a, 2022b38, n.d.-a39, n.d.-b40). Most of the respondents identified as Hispanic or Latinx (64.4%), with the remaining respondents being distributed among other racial categories. Approximately three-quarters (77.0%) of the sample had earned a bachelor’s degree, which is disproportionately higher than the total population of the islands. The average size of a respondent’s household was 2.89 (Standard Deviation (SD) = 1.36) persons, with only 24% of households sampled having at least one child under 18 years of age and 22% of households indicated that they had someone 65 years of age or older residing in the household. Over half of the sample (56.1%) identified that they were employed full-time, with a median income of respondents earning $30,000–$39,000 a year.

Data Analysis

Due to the nonparametric nature of the data, nonparametric statistical testing was used to analyze the data including chi-square tests and McNemar’s tests. Additionally, optimized hot spot analyses were used in ArcGIS Pro to identify statistically significant clusters of high (hot spot) and low (cold spot) values. To conduct the hot spots analyses, the bounding polygons were set to municipality shapes and the analysis field was the response to the questionnaire for each respondent.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

Researchers need to be particularly mindful of their positionality and ensure the reciprocity of established relationships when conducting research (Secules et al., 202141). The aim was to engage both practitioners and academics early in the process to include expertise from public health, epidemiology, emergency management, geosciences, meteorology, marketing, and communications. The research team paid close attention to the design of the survey instruments, data collection methods, and analyses. Everyone on the research team was engaged in reviewing existing literature, the grant writing process, research design, survey development, testing the survey instrument, dissemination, and logistics (Oulahen, 202042). Understanding political, institutional, social, and cultural dynamics provided further insight into ethical considerations throughout the study.

Results

Vaccination Status and Hurricane Evacuation

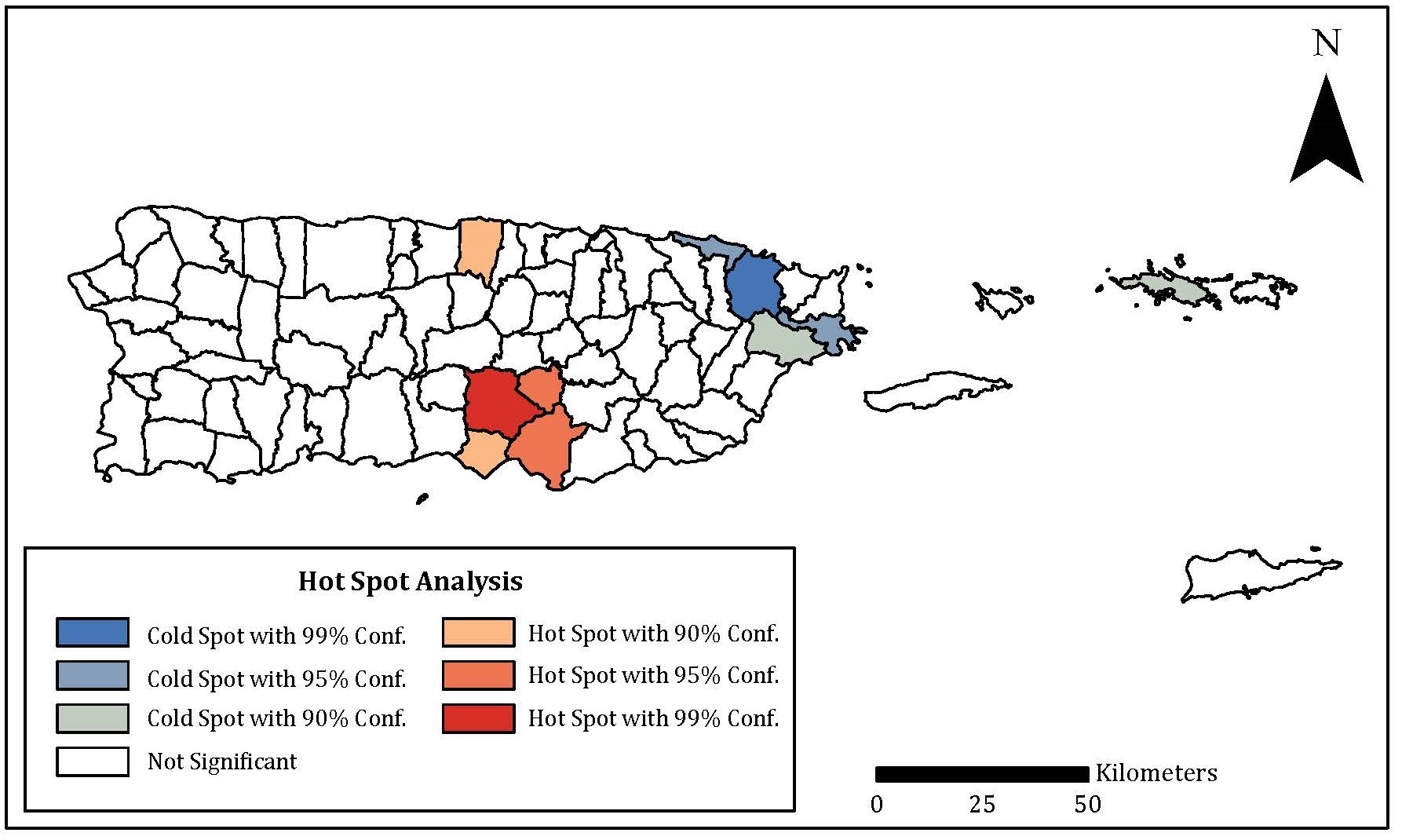

At the time of this survey, 57.4% of the respondents were fully vaccinated against COVID-19, with 21.6% receiving at least the first dose of the vaccine. A small portion of respondents had no intention of receiving the vaccine (8.5%) or were waiting until it has been out longer (7.1%). Overall, fewer respondents residing (X2(6) = 6.382, p < 0.001) in the U.S. Virgin Islands were vaccinated than in Puerto Rico. There was a significant (p ≤ 0.05) clustering of respondents vaccinated in south-central Puerto Rico (Coamo, Salinas, Aibonito), while there was a significant (p ≤ 0.05) clustering of unvaccinated respondents from eastern Puerto Rico (Loíza, Río Grande, Ceiba) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hot Spot Analysis Assessing the Spatiality of Vaccination Status

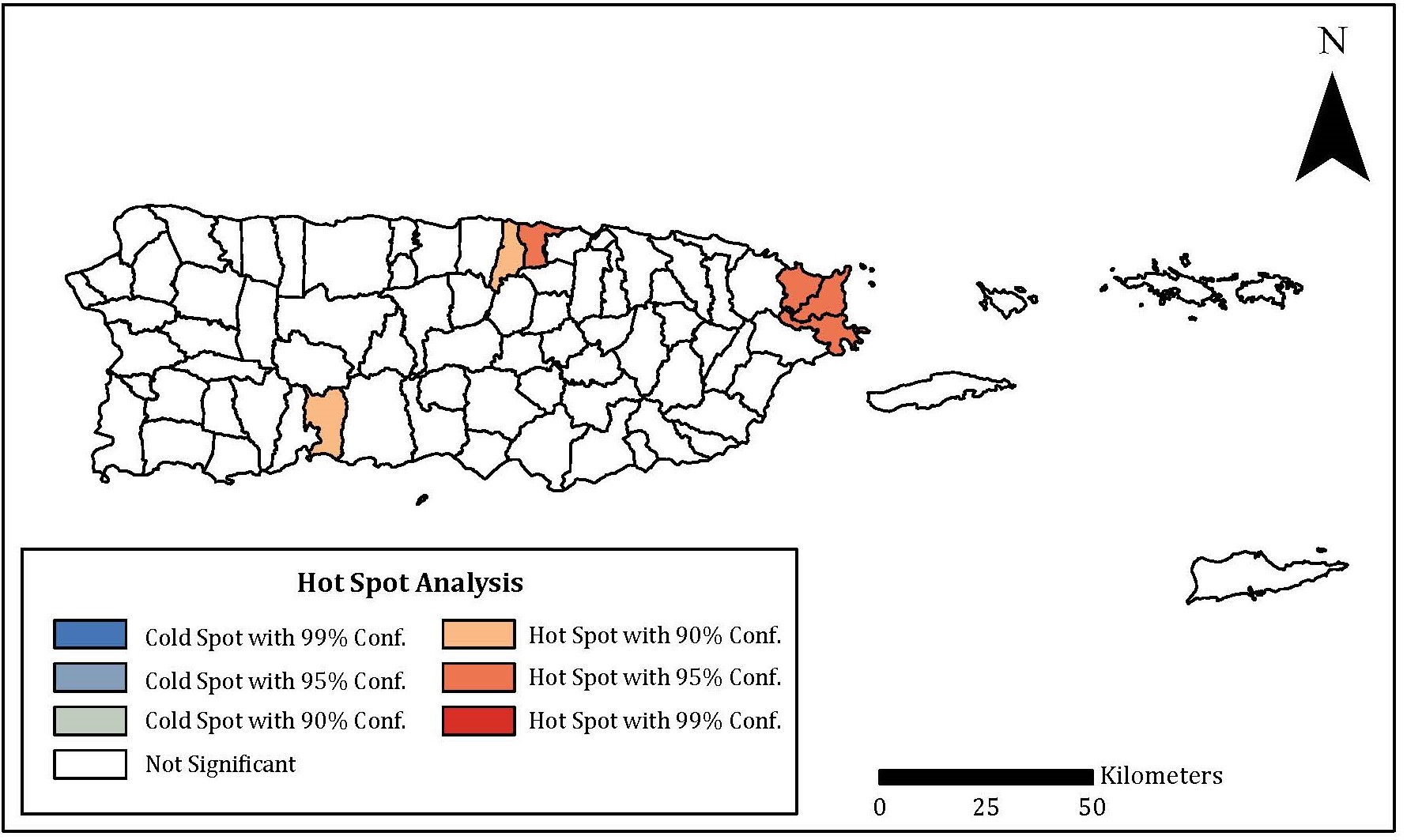

When asked whether the vaccination status of respondents would affect their decision to evacuate for a hurricane, an overwhelming majority (72.6%) of respondents replied “no.” Most respondents specifically listed that they would either not change anything about their evacuation plans (36.3%) or would reconsider going to a shelter (19.6%) depending on their vaccination status. However, vaccination status and deciding whether to evacuate or stay home during a hurricane are significantly (X2(2) = 7.120, p = 0.028) associated. Interestingly, those who are unvaccinated responded that they are more likely to evacuate during a storm than those who are vaccinated. Hot spot analysis found that there was a significant (p ≤ 0.05) clustering of respondents from eastern Puerto Rico (Ceiba, Fajardo, Luquillo) and Dorado that were more likely to have their vaccination status affect their evacuation plans during a hurricane (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Hot Spot Analyses Assessing Areas Where Vaccination Status Significantly Affects a Household’s Hurricane Evacuation Decision

Hurricane Evacuation Intentions During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Responses were analyzed to determine if respondents’ attitudes towards hurricane evacuations changed between the pre- and post-vaccine eras of the COVID-19 pandemic. There was no significant (X2(6) = 3.101, p = 0.796) difference in intention to evacuate to a shelter prior to COVID-19 vaccination among those who consider themselves vulnerable to COVID-19 in comparison to those who do not. This is interesting because those who consider themselves vulnerable to COVID-19 are significantly (X2(6) = 19.673, p = 0.003) more likely to believe that going to a disaster shelter is riskier than sheltering at home due to the spread of COVID-19.

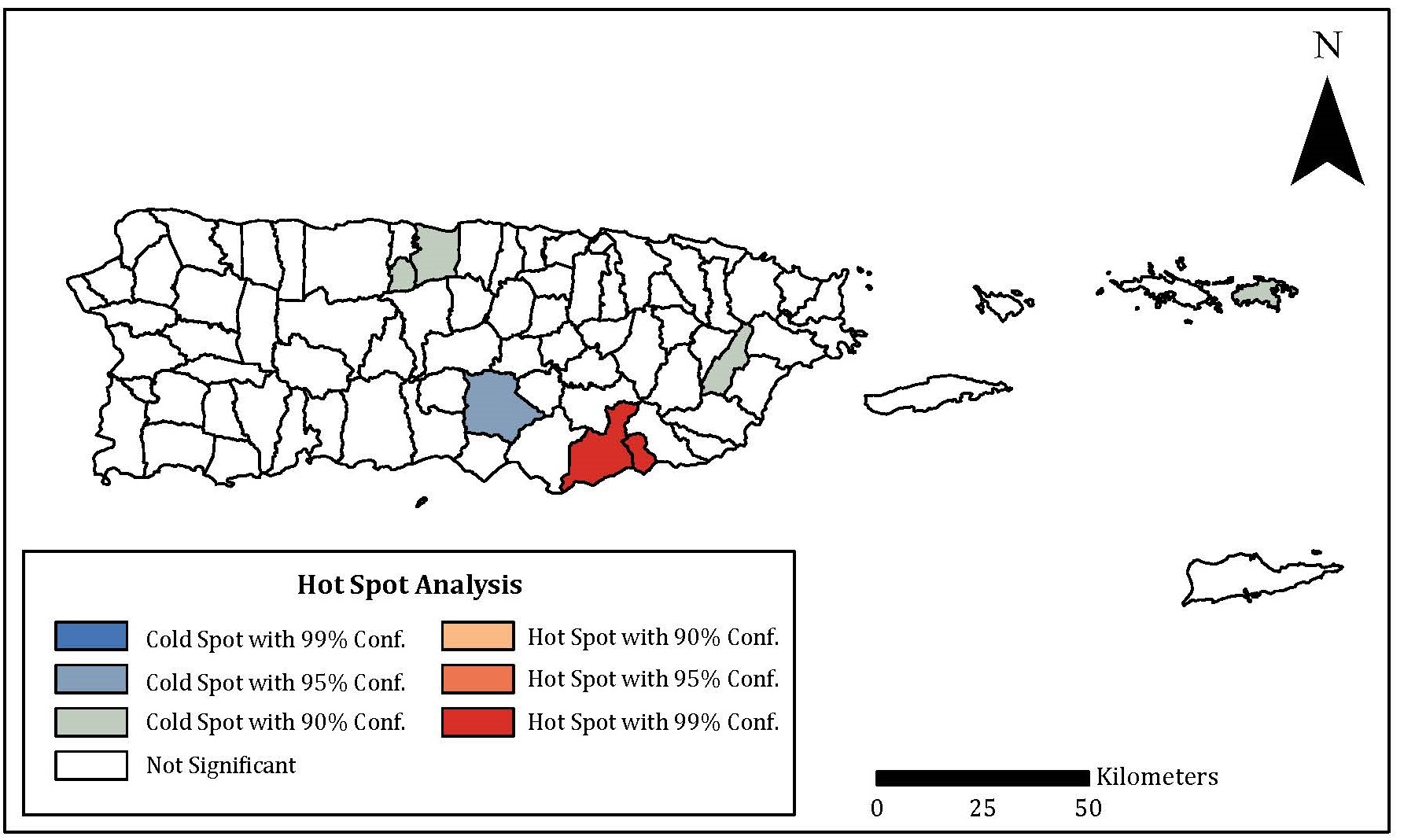

Hot spot analyses revealed that respondents in southeastern Puerto Rico (Lajas and Guánica) are significantly (p ≤ 0.05) less likely to evacuate for a hurricane if ordered to by emergency managers. When asked whether respondents would have evacuated to a shelter if needed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, most respondents suggested they “definitely” would not have evacuated to a hurricane shelter if needed (34.2%), while 30.4% of respondents said they probably would have (hot spot analysis of locations provided in Figure 4). There was no significant difference (X2(1) = 2.839, p = 0.092) between the median score of the vaccinated versus the unvaccinated for this question. The likelihood of respondents planning to utilize a shelter during the 2021 hurricane season aligned with the likelihood prior to the pandemic, as nearly 40% of respondents “definitely” would not evacuate to a shelter (x̅ = 2.98+/-0.98).

Figure 4. Hot Spot Analyses Assessing Respondents' Willingness to Evacuate to a Shelter During the 2021 Hurricane Season and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Perception of Others’ Vaccination Status and Hurricane Evacuation

At the time of the survey, respondents generally believed that more people on their respective islands were unvaccinated (63.7% +/- 15.9%) than those that were vaccinated against COVID-19. Not only were more residents vaccinated in Puerto Rico, but Puerto Rico residents considered themselves more vulnerable to COVID-19 (X2(2) = 21.022, p < 0.001) than U.S. Virgin Islands residents. Interestingly, Puerto Rico residents also perceived that more residents on their island were vaccinated (x̅ = 37.2, SD = 16.0) compared to residents of the U.S. Virgin Islands (x̅ = 32.1, SD = 14.9). Those who consider themselves vulnerable to COVID-19 were significantly (X2(4) = 13.372, p = 0.010) more likely to answer “yes” to having a different hurricane evacuation plan if more people on their island were vaccinated. There is a significant (p ≤ 0.05) clustering of respondents from Santa Isabel and Florida (Puerto Rico) who were more likely to suggest that their evacuation plans would change if more people on their island were vaccinated, while there is a significantly (p ≤ 0.05) cluster of respondents from Añasco who were less likely to be influenced by vaccination rates.

Most respondents (43.7%) believed that it was “definitely true” (x̅ = 1.86+/-0.93) that the risks of being in a disaster shelter during COVID-19 were worse that the risks posed by a hurricane. However, approximately 40% of the respondents suggested that safeguards would “probably” be adequate to prevent the spread of COVID-19, while 26.7% suggested it “probably” would not (2.49 +/-0.96). The decision to evacuate does not appear to be diminished by an erosion of public trust with local authorities and institutions, as 55.4% of respondents suggest that since the pandemic, their faith in local authorities has remained the same. There is a significant (p ≤ 0.01) clustering of respondents in Arecibo and Florida (Puerto Rico) that are more likely to believe that the safeguards in a hurricane shelter provided by officials would be inadequate to prevent the spread of COVID-19, while there is a significant (p ≤ 0.05) clustering of respondents in Camuy that believe they would be adequate.

Discussion

Vaccination Status and Hurricane Evacuation Plans

Our results indicate that most respondents (72.6%) report that vaccine status would not affect their decision to leave their home during a hurricane. Findings indicate that 66% of respondents would stay home and 17% would go to the home of a family member or friend. Only 1% of respondents reported they would leave their home to go to a public shelter. This may have to do with an underlying dissatisfaction with public shelters paired with a strong preference to endure the hurricane in a home setting with family and friends rather than in a public shelter with strangers. Additionally, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, family members may have not felt comfortable abandoning individuals who preferred to be in a home setting rather than sheltering with others. These results are consistent with Collins et al.’s (2021a, 2022a) study prior to vaccine availability, which showed most people would rather endure a hurricane and its risks than go to a public shelter.

Vaccine Availability and Hurricane Evacuation Plans

Comparing respondents who consider themselves vulnerable to COVID-19 versus those who do not, there was no significant difference in the intention of respondents to evacuate to a hurricane shelter prior to the availability of the COVID-19 vaccination. This is interesting because those who consider themselves vulnerable to COVID-19 are significantly more likely to believe that going to a public shelter is riskier than sheltering at home due to the spread of COVID-19. This demonstrates an underlying lack of confidence in public shelters, and a strong preference to stay at home or evacuate to the home of a family member or friend. It may be that this preference overrides the availability of vaccines for COVID-19.

Results indicated that 34.2% of respondents suggested they “definitely” would not have evacuated to a hurricane shelter if needed, while 30.4% of respondents said they probably would evacuate to a shelter. Overall, the average score of the responses (2.75 +/- 1.08) to this four-point Likert scale question suggests residents would “probably” not evacuate to a shelter. Responses reflect an underlying dissatisfaction with public shelters. This could provide motivation for emergency management experts to re-examine their approach toward opening public shelters to include how they are organized and the pre-staged resources that are available on site. Messaging to the public about the importance of public shelters as a low cost, protective measure for at-risk populations could also be beneficial. Some important considerations for improving existing shelters are to offer space and services for individuals managing chronic diseases, to provide mental health services, to establish safe and free transportation to and from the shelter, to provide accommodations for pets, to have a security presence at the shelter, and to establish a process for evacuees to report any incidents that may occur (Campbell et al., 2021; Koloushani et al., 2022; Lazo et al., 2015; Whytlaw et al., 2021).

Perception of Other People’s Vaccination Status

Results show that even if a greater percentage of their respective islands were vaccinated, most (59.0%) respondents suggested that their evacuation plans would remain consistent. However, those who consider themselves vulnerable to COVID-19 were significantly more likely to answer “yes” to having a different hurricane evacuation plan if more people on their island were vaccinated. This may be reflected by the response from most respondents (43.7%) who believed that it was “definitely true” that the risks of being in a disaster shelter during COVID-19 were worse than the risks posed by a hurricane. This is consistent with the findings from the two previous research questions. The belief that the risks of being in a shelter are worse than the risks posed by a hurricane could also be reinforced by the fact that Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands routinely faces the threat of hurricanes, and many citizens have spent their lives either sheltering in place during a hurricane, or staying with a family member, friend, or neighbor.

Conclusions

Public Health Implications

Public health emergency planners who coordinate mass care can learn from the specific challenges highlighted by this study to inform future shelter planning. One main need is more effective communications directed to the public and communities at greater risk due to inequities in their social determinants of health, especially in access to medical services and medications, and consideration for the built environment. Communications should include language that explains the benefits a hurricane shelter has to offer residents—from having access to medical care, safe drinking water, and electricity to providing adequate spacing and a facility able to withstand hurricane force winds. For instance, shelter planning and preparedness measures could include having a generator to power life-saving medical equipment that is needed to maintain the health and well-being of evacuees, stockpiling commonly used medications and oxygen in advance, and providing personnel certified to respond to public health and medical emergencies (Breeden et al., 202043; Storch et al., 201944).

Government planning to protect the health and well-being of populations threatened by hurricanes and the COVID-19 pandemic have increased in complexity, as we have seen in the existing literature since the start of the pandemic (Pei et al., 2020; Whytlaw et al., 2021). Government officials need to develop and communicate clear and concise information regarding evacuation orders for certain municipalities that may be impacted more than others based upon the trajectory of the hurricane, social determinants of health, and other factors like living in a flood zone, or in housing that cannot withstand sustained high winds associated with hurricanes. Hot spot analyses revealed a significant clustering of respondents from Ceiba, Fajardo, Luquillo, and Dorado (Puerto Rico) that indicated their vaccination status would likely affect their hurricane evacuation plans. Whereas a cluster of respondents in the municipalities of Lajas and Guánica were less likely to evacuate for a hurricane even if emergency managers issued an evacuation order. A cluster from Coamo (Puerto Rico) indicates they are significantly less likely to evacuate to a shelter during the pandemic, while clusters in Arecibo and Florida (Puerto Rico) believe will be inadequate safeguards in the hurricane shelters to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Based upon these survey results, the decision to evacuate to a public shelter or to shelter in place should inform mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery strategies to promote population health during future disasters and hazard events. Households and families should have emergency preparedness plans that include care for members with disabilities, older adults, and individuals who are chronically ill or medicine dependent. A major part of these plans should include criteria for decisions to evacuate to a mass care shelter.

Limitations

One limitation that needs to be acknowledged is that the results are not generalizable to the entire population of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands because the sample was not representative. Due to the sampling procedures and use of an established network to find respondents, results from this study may be biased and not truly representative of the Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands populations, as estimated by the 2020 U.S. Census. For example, respondents were disproportionately women, obtained higher levels of education, and had a higher annual income than the territories' averages (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022a, 2022b).

Future Research Directions

Since this study, Hurricane Fiona significantly impacted Puerto Rico on September 18, 2022. Substantial damage from heavy rains brought more than 30 inches of water to some areas, causing massive flooding, landslides, and rockslides (NOAA, 2022). Puerto Rico has weak, antiquated, and inefficient food, energy, and water systems damaged by the extensive rainfall and flooding following Hurricane Fiona. Almost a year after Hurricane Fiona, there is now a need to understand both what people actually did regarding evacuation and what considerations influenced their evacuation decision. Of particular interest is that individuals have continued to have a negative perception of public shelters’ ability to safeguard against COVID-19, which was coupled with a high rate of respondents that do not intend to use shelters. Furthermore, there is a need to assess public health threats to recovery pertaining to essential lifelines (energy, water, food, and health services), the needs of different communities, and how that may impact their decision to evacuate during a hurricane. Understanding residents' perceptions of response and recovery efforts that pose a challenge (both short-term and long-term) for communities can provide further understanding of public health interventions for future planning. The following are questions we aim to address in future research:

- What challenges remain in Puerto Rico one year after the impact of Hurricane Fiona?

- Did access to potable water and electricity affect individuals' decisions to evacuate to a public shelter, hotel, or home of a family member/friend? How did their dependency on electricity for medical reasons impact their decision-making?

- How did Hurricane Fiona affect COVID-19 pandemic public health mitigation practices? Did vaccine availability affect people’s risk perceptions, preparedness planning, and evacuation decisions?

- How will the findings of residents’ risk perception related to Hurricane Fiona, preparedness planning, and evacuation decisions differ by geographic location, vaccination status, economic earnings, level of education, and other social determinants of health?

- Did those with underlying health conditions and high social vulnerability in flood-prone areas choose to shelter in place due to COVID-19?

- Did people view public shelters as overtly risky due to concerns over the pandemic now that the COVID-19 vaccine is available, and did they instead choose to shelter in place despite a recommendation to evacuate to a safer location or a government-operated shelter staffed by local authorities?

Acknowledgments. We appreciate the support of the Division for Disaster Response and Emergency Preparedness at the Puerto Rico Public Health Trust, particularly Melanie Rodriguez and Lizmariel Tirado. We appreciate the support of Amy Polen who was instrumental in creating the survey questions with the team. We thank Dominic Del Pino for a final review of our report. We acknowledge our extensive stakeholder team for their efforts in survey question feedback, testing, and distribution. We thank the Natural Hazards Center for providing the opportunity to conduct this research.

References

-

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2022). State climate summaries 2022: Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. National Centers for Environmental Information. https://statesummaries.ncics.org/chapter/pr/ ↩

-

Collins, J., Polen, A., Dunn, E., Maas, L., Ackerson, E., Valmond, J., Morales, E., & Colón-Burgos, D. (2021a). Compound Hazards, Evacuations, and Shelter Choices: Implications for Public Health Practices in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Public Health Report Series, 6. Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/compound-hazards-evacuations-and-shelter-choices ↩

-

Collins, J., Polen, A., Dunn, E., Maas, L., Ackerson, E., Valmond, J., Morales, E., & Colón-Burgos, D. (2022a). Hurricane hazards, evacuations, and sheltering: Evacuation decision-making in the pre-vaccine era of the COVID-19 pandemic in the PRVI region. Weather, Climate, and Society, 14(2), 451–466. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-21-0134.1 ↩

-

Jury, M. R., Chiao, S. & Cécé, R. (2019). The intensification of Hurricane Maria 2017 in the Antilles. Atmosphere, 10(10), 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10100590 ↩

-

National Hurricane Center. (2022). Tropical Cyclone Climatology. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/climo/?text ↩

-

Pan American Health Organization. (2017). Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Situation Report 8. https://www.paho.org/disasters/dmdocuments/PAHOWDC_SituationReport8_Hurricane%202017_22Sept2017.pdf ↩

-

Chowdhury, M. A. B, Fiore, A. J., Cohen, S. A., Wheatley, C., Wheatley, B., Balakrishnan, M. P., Chami, M., Scieszka, L., Drabin, M., Roberts, K. A., Toben, A. C., Tyndall, J. A., Grattan, L. M., & Morris, G. (2019). Health impact of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on St Thomas and St John, US Virgin Islands, 2017–2018. American Journal of Public Health, 109(12), 1725–1732. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305310 ↩

-

Wang, G., Kearns, T. J., Yu, J., & Saenz, G. (2014). A stable reference frame for landslide monitoring using GPS in the Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands region. Landslides, 11, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-013-0428-y ↩

-

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, August 30). Vaccinating people in Puerto Rico. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/health-departments/features/puerto-rico.html ↩

-

Cutter, S. L., Boruff, B. J., & Shirley, W. L. (2003). Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Social Science Quarterly, 84(2), 242–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6237.8402002 ↩

-

Tierney, K. J., Lindell, M. K., & Perry, R. W. (2001). Facing the unexpected: Disaster preparedness and response in the United States. Joseph Henry Press. ↩

-

Aldrich, N., & Benson, W. F. (2008). Disaster preparedness and the chronic disease needs of vulnerable older adults. Preventing Chronic Disease, 5(1), A27. ↩

-

Brown, L. M., Dosa, D. M. Thomas, K., Hyer, K., Feng, Z., & Mor, V. (2012). The effects of evacuation on nursing home residents with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, 27(6), 406–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317512454709 ↩

-

Donner, W. R., & Lavariega-Montforti, J. (2018). Ethnicity, income, and disaster preparedness in Deep South Texas, United States. Disasters, 42(4), 719–733. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12277 ↩

-

Elder, K., Xirasagar, S., Miller, N., Bowen, S. A., Glover, S., & Piper, C. (2007). African Americans' decisions not to evacuate New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina: A qualitative study. American Journal of Public Health, 97, S124–S129. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.100867 ↩

-

Sohn, W., & Kotval-Karamchandani, Z. (2023). Risk perception of compound emergencies: A household survey on flood evacuation and sheltering behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainable Cities and Society, 94, 104553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104553 ↩

-

Demuth, J. L., Morss, R. E., Lazo, J. K., & Trumbo, C. (2016). The effects of past hurricane experiences on evacuation intentions through risk perception and efficacy beliefs: A mediation analysis. Weather, Climate, and Society, 8(4), 327–344. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-15-0074.1 ↩

-

Lazo, J. K., Bostrom, A., Morss, R. E., Demuth, J. L. & Lazrus, H. (2015). Factors affecting hurricane evacuation intentions. Risk Analysis, 35(10), 1837–1857. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12407 ↩

-

Eisenman, D. P., Cordasco, K. M., Asch, S., Golden, J. F., & Glik, D. (2007). Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Public Health, 97, S109–S115. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.084335 ↩

-

Campbell, N. M., Morss, R. E., Lindell, M. K., & Gutmann, M. P. (2021). Emergency evacuation and sheltering during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Academies Press. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/26084/ ↩

-

Ford, J. D., Zavaleta-Cortijo, C., Ainembabazi, T., Anza-Ramirez, C., Arotoma-Rojas, I., Bezerra, J., Chicmana-Zapata, V., Galappaththi, E. K., Hangula, M., Kazaana, C., Lwasa, S., Namanya, D., Nkwinti, N., Nuwagira, R., Okware, S., Osipova, M., Pickering, K., Singh, C., Berrang-Ford, L., Hyams, K., Miranda, J. J., Naylor, A., New, M., & van Bavel, B. (2022). Interactions between climate and COVID-19. The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(10), e825-e833. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00174-7 ↩

-

Pei, S., Dahl, K. A., Yamana, T. K., Licker, R., & Shaman, J. (2020). Compound risks of hurricane evacuation amid the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. GeoHealth, 4(12), e2020GH000319. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GH000319 ↩

-

Phillips, C. A., Caldas, A., Cleetus, R., Dahl, K. A., Declet-Barreto, J., Licker, R., Merner, L. D., Ortiz-Partida, J. P., Phelan, A. L., Spanger-Siegfried, E., Talati, S., Trisos, C. H., & Carlson, C. J. (2020). Compound climate risks in the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Climate Change, 10, 586–588. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0804-2 ↩

-

Shultz, J. M., Kossin, J. P., Ali, A., Borowy, V., Fugate, C., Espinel, Z., & Galea, S. (2020). Superimposed threats to population health from tropical cyclones in the prevaccine era of COVID-19. The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(11), e506–e508. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30250-3 ↩

-

Demuth, J. L., Morss, R. E., Morrow, B. H., & Lazo, J. K. (2012). Creation and communication of hurricane risk information. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 93(8), 1133–1145. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00150.1 ↩

-

Schnall, A. H., Roth, J., Ekpo, L. L., Guendel, I., Davis, M., & Ellis, E. M. (2019). Disaster-related surveillance among US Virgin Islands (USVI) shelters during the Hurricanes Irma and Maria response. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 13(1), 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2018.146 ↩

-

Whytlaw, J. L., Hutton, N., Yusuf, J. E., Richardson, T., Hill, S., Olanrewaju-Lasisi, T., Antwi-Nimarko, P., Landaeta, E., & Diaz, R. (2021). Changing vulnerability for hurricane evacuation during a pandemic: Issues and anticipated responses in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 61, 102386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102386 ↩

-

Collins, J., Polen, A., McSweeney, K., Colón-Burgos, D., & Jernigan, I. (2021b). Hurricane risk perceptions and evacuation decision-making in the age of COVID-19. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 102(4), E836–E848. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-20-0229.1 ↩

-

Collins, J., Polen, A., Dunn, E., Jernigan, I., McSweeney, K., Welford, M., Lackovic, M., Colon-Burgos, D., & Zhu, Y. (2022b). Hurricanes Laura and Sally: A case study of evacuation decision-making in the age of COVID-19. Weather, Climate, and Society, 14(4), 1231–1245. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-21-0160.1 ↩

-

Zhao, T., M. Jia, T. Tang, & Y. Sun. (2022). Perception of hurricane and COVID-19 risks for household evacuation and shelter intentions. The Professional Geographer, 75(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2022.2103722 ↩

-

Botzen, W. J. W., Mol, J. M., Robinson, P. J., Zhang, J., & Czajkowski, J. (2022). Individual hurricane evacuation intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights for risk communication and emergency management policies. Natural Hazards, 111, 507–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-05064-2 ↩

-

Morss, R. E., Demuth, J. L., Lazo, J. K., Dickinson, K., Lazrus, H., & Morrow, B. H. (2016). Understanding public hurricane evacuation decisions and responses to forecast and warning messages. Weather and Forecasting, 31(2), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1175/WAF-D-15-0066.1 ↩

-

Cox, D., Arikawa, T., Barbosa, A., Guannel, G., Daisuke, I., Kennedy, A., Li, Y., Mori, N., Perry, K., Prevatt, D., Roueche, D., Shimozono, T., Simpson, C., Shimakawa, E., Shimura, T., & Slocum, R. (2019). Hurricanes Irma and Maria post-event survey in US Virgin Islands. Coastal Engineering Journal, 61(2), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/21664250.2018.1558920 ↩

-

Shultz, J. M., Kossin, J. P., Shepherd, J. M., Ransdell, J. M., Walshe, R., Kelman, I., & Galea, S. (2019). Risks, health consequences, and response challenges for small-island-based populations: Observations from the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 13(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2018.28 ↩

-

Acosta, R. J., Kishore, N., Irizarry, R. A., & Buckee, C. O. (2020). Quantifying the dynamics of migration after Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(51), 32772–32778. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2001671117 ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2022a). Puerto Rico Quick Facts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/PR ↩

-

Meng, S., Halim, N., Karra, M., & Mozumder, P. (2022). Understanding household evacuation preferences during the COVID-19 pandemic in Puerto Rico. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4011468 ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2022b). 2020 Island areas Censuses data on demographic, social, economic and housing characteristics now available for the US Virgin Islands. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/2020-island-areas-us-virgin-islands.html ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.-a). Puerto Rico Demographics from the 2021 ACS 1-year estimates [Data set]. Retrieved July 27, 2023, from https://data.census.gov/table?q=Puerto+rico+demographics ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.-b). U.S. Virgin Island Demographics from the 2020 Census [Data set]. Retrieved July 27, 2023, from https://data.census.gov/table?g=040XX00US78&d=DECIA+U.S.+Virgin+Islands+Demographic+Profile&tid=DECENNIALDPVI2020.DP1 ↩

-

Secules, S., McCall, C., Mejia, J. A., Beebe, C., Masters, A. S., Sánchez‐Peña, M. L., & Svyantek, M. (2021). Positionality practices and dimensions of impact on equity research: A collaborative inquiry and call to the community. Journal of Engineering Education, 110(1), 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20377 ↩

-

Oulahen, G., Vogel, B., & Gouett-Hanna, C. (2020). Quick response disaster research: Opportunities and challenges for a new funding program. International Journal for Disaster Risk Science, 11, 568–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-020-00299-2 ↩

-

Breeden, J., Adams, R., Peek, L., Thomas, T. N., & Jansson D. R. (2020). Introduction: Mass sheltering and disasters. Research Counts Mass Sheltering Special Collection. https://hazards.colorado.edu/news/research-counts/special-collection/introduction-mass-sheltering-and-disasters ↩

-

Storch E. A., Shah, A., Salloum, A., Valles, N., Banu, S., Schneider, S. C., Kaplow, J., & Goodman, W. K. (2019). Psychiatric diagnoses and medications for Hurricane Harvey sheltered evacuees. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(7), 1099–1102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00378-9 ↩

Collins, J., Dunn, E., Hartnett, J., Maas Cortes, L., & Jones, R. (2023). Evacuation Decision-Making Post-Vaccine: Implications of Compound Hazards in the U.S. Territories (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 35). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/evacuation-decision-making-post-vaccine