Compound Hazards, Evacuations, and Shelter Choices

Implications for Public Health Practices in the Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands

Publication Date: 2021

Executive Summary

Overview

While research relating to hurricane evacuation behavior and perceptions of the risk has grown throughout the years, there has been very little understanding of compounding risks. Currently, the global pandemic (COVID-19) on top of hurricanes and other hazards (such as flooding and landslides) will impact people’s evacuation decisions and subsequent health and survival outcomes. The U.S. territories have no previous experience with hurricane evacuations during a pandemic. Following this rationale, our research examines how the COVID-19 pandemic (and associated health risks) will add to existing hazards associated with hurricanes and affect risk perceptions, preparedness planning, and evacuation decisions. The study will explore if resident perceptions of risk have changed due to the current pandemic and if they have plans that incorporate the need to evacuate to a friend, family, or alternative location if they are in vulnerable areas at risk to storm surge, landslides, or flooding. It will also look at how we can apply this knowledge for future hazard mitigation planning during a disease outbreak or pandemic.

This study takes into consideration how resident risk perception, preparedness planning, and evacuation decisions differ by location, type of housing, political affiliation, economic earnings, level of education, and other social determinants of health. It further examines if those with underlying health conditions and high social vulnerability in flood-prone areas will choose to shelter in place due to concern of contracting COVID-19. The research analyzes perceived susceptibility to determine if people view public shelters as overly risky due to concerns about COVID-19 and whether they will instead choose to shelter in place despite a recommendation to evacuate to a safer location or a government-operated shelter staffed by local authorities.

Research Design

A survey was disseminated during the 2020 hurricane season, before vaccines were available. Four hundred fifty-seven respondents completed the survey of which 321 were completed in Spanish, and the remaining 136 were completed in English. The sample for each survey was obtained through convenience and snowball sampling using an extensive network of personal and professional connections in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, who further disseminated the survey to their professional contacts or directly to the public. Data were cleaned and organized logically from their original Qualtrics output. After these procedures, data were analyzed using the IBM statistical software program SPSS v. 26 using a variety of statistical tests. Furthermore, mapping was produced using ArcGIS Pro.

Preliminary Findings

One key finding is that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound effect on how people make decisions to evacuate. More than half of the survey respondents considered themselves vulnerable to COVID-19, and when asked about their actions in the 2020 hurricane season, individuals who would have previously evacuated to a shelter would choose not to during the pandemic, reflecting that public shelter usage has the potential to decrease when the decision is coupled with COVID-19 threats. Additionally, individuals were shown to have a negative perception of public shelter options, with approximately half of the respondents having little faith in the shelters’ ability to maintain social distancing and other preventative actions. More than half of the respondents stated that they would definitely shelter-in-place to minimize exposure to large groups in the shelter, and 75.5% of the respondents thought that the risks of being in a shelter were higher than those that they would have to endure if they were to stay home during a hurricane.

Conclusions

Determining and prioritizing needs for congregate shelters provides an opportunity to reduce the number of shelters with an increased understanding of demand. This helps forecast future staffing needs and identify gaps in an already fatigued workforce due to the pandemic. Strengthening our understanding of perceived barriers and facilitators to evacuation decisions allows for public health interventions designed to increase self-efficacy and support cues to action. To address some of these concerns there is a need to engage the community in preparedness planning, share information on updated shelter plans, and utilize social cues during the response phase to help build trust. Findings identify areas of need for targeted messaging and campaigns to increase trust and encourage residents to evacuate if needed while utilizing information sources most frequently relied on prior to and during a hurricane.

Introduction and Literature Review

Early warning systems, evacuations, and sheltering programs serve as a protective action for those at risk to various threats along coastal communities in the island territories, including high winds, surge inundation, rainfall flooding, and landslides. The extremely high levels of hurricane activity in 2020 (Klotzbach et al., 20201) and expected high level of activity in 2021 (Klotzbach et al., 20212) are compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. Planning and coordination among emergency management and public health and human services experts in Puerto Rico (PR) and the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) are needed to address the compounding threats during the pandemic. Threats are not only to individuals and families, but to the health and social systems as a whole that are dedicated to protecting population health and safety. Ensuring priorities and activities are realistic, well planned, and clearly communicated requires a whole community approach (Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], 20113). Engaging local residents in the planning process provides jurisdictional government entities with the information needed to strengthen existing plans if confronted with a major hurricane and tailor these protective actions to meet the needs of the community. Formative research conducted among populations at risk provides data needed to identify existing barriers for accessing a safe space, establish interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality, and ensures public messaging and education positively influence the decision-making processes. This study takes a bottom-up approach that places emphasis on local government and community actions for disaster risk reduction (Burger & Gochfeld, 20204). Baseline knowledge of risk perception of compounding threats during a pandemic, the first of its kind in the Puerto Rico-U.S. Virgin Islands (PRVI) region, aims to support evidence-informed decisions and capacity building for public health preparedness planning.

Compounding Hazards: Hurricanes, Flooding, and Landslides

Flood events on coastal communities are a significant stressor that is increasing due to sea-level rise and the frequent exposure to weather hazards. The rate of sea-level rise has increased fourfold in recent decades (Jury, 20185). It is expected that island territories will experience a substantial impact of flooding due to direct exposure to tropical storms and a strong dependency on coastal resources (Vitousek et al., 20176). Our current knowledge focuses on landfalling events in the U.S. mainland, with less work on the lower latitudes (Elsner et al., 19997, 20008; Jury et al., 20129). More than 15% of all Atlantic hurricanes make landfall in the Caribbean Antilles Islands between August and September (Jury et al., 201910). Destructive impacts leading to severe infrastructure loss and environmental impacts such as power outages, damaged infrastructure, saltwater intrusion, and coastal erosion are unavoidable on small islands when exposed to high winds, flash floods, and landslides (Cox et al., 201911). Ultimately, the PRVI region is ideal for studying compounding hazards as the area often experiences storm surges, intense rain, and subsequent flooding with potential landslide risks and earthquakes to consider. In addition to this, the COVID-19 pandemic brings additional concerns to the confluence of these hazards.

Due to the mountainous terrain and tropical climate of the PRVI region of the Caribbean, landslides are the primary natural hazard (Wang et al., 201412) and they can be exacerbated by the effects of a hurricane. In 2017, Hurricane Maria produced rainfall amounts sufficient to trigger more than 70,000 landslides across all mountainous areas of PR (Bessette-Kirton et al., 201913). This resulted in dislodged homes from their foundations on steep hillsides, disrupted transportation routes, and loss of life—both direct and indirect. Additionally, landslides can result in cascading post-disaster emergencies as they have the potential to destroy roads, making movement across an island near-impossible. For example, on St. John in the USVI, following the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, a major east-west road became blocked by a landslide, restricting access for ambulances to provide immediate help to those reeling from the storm (Peters, 201714).

Hurricane Evacuation Orders During a Pandemic

While hurricane evacuation behavior and risk perception research has grown throughout the years, historically research identified a correlation between evacuation rates and low-lying areas at high-risk along with factors such as housing and severity of the storm (Baker, 199115, 199516; Gladwin et al., 200117; Whitehead et al., 200018). Additional studies have also explored how past experiences have influenced evacuation intentions and how individual assessments were a vital component of the decision-making process (Demuth et al., 2016[^Demuth et al]; Dow & Cutter, 200019). Whereas research on socioeconomic characteristics and social capital in correlation with evacuation behavior as a means of assessing social equity for evacuation planning has provided a deeper understanding of vulnerability and equity (Eisenman et al., 200720; Elder et al., 200721; Miller, 200722; Moore et al., 200423). Over the years, there has been a heightened focus on the role of forecasting and risk communication to identify more effective channels of information sharing and synthesis for decision-making (Collins et al., 201724, 201825; Morss et al., 201626; Senkbeil et al., 201927; Sherman-Morris et al., 201128).

Minimal research on evacuation behavior has been conducted in the PRVI islands (Morrow & Gladwin, 2014a29, 2014b30; Shultz et al., 201931) with little understanding of how compounding risks will impact evacuation decisions and subsequent health and survival outcomes. Understandably, much of the U.S. population, including the U.S. territories, have no prior experience planning for hurricane evacuations during a pandemic and public health planners need to rapidly assess the potential societal impacts to anticipate various worse case scenarios (Buckle, 200632; Demuth et al., 201233).

COVID-19 is the fifth pandemic to affect the world in the past hundred years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 201834). Since December 1, 2019, COVID-19 has spread to 198 countries with 132 million cases and more than 2,867,242 deaths worldwide as of April 2021 (World Health Organization [WHO], 202135). While guidance from hurricane experts reminds residents that they should prepare the same for every season, regardless of how much activity is predicted, preparing for hurricane seasons during the global pandemic is causing individuals to re-think their evacuation plans. Should a major hurricane occur in the PRVI region during the COVID-19 pandemic, residents will be making complex decisions as they balance their need to evacuate and the risk of infection. The pandemic increases the complexity of planning for hurricanes and the related hazards (landslides/flooding) as social distancing is in direct conflict with human mobility and congregation in a disaster. Disease surveillance and addressing the needs of clients in the general population and special medical needs shelters poses additional challenges to public health preparedness and emergency management authorities in both U.S. territories (Schnall et al., 201936). In the USVI, there are also limited options for sheltering, especially when considering the demands of spaces conducive to social distancing.

Given that social distancing is warranted, people may risk sheltering in place to avoid COVID-19 exposure despite being in an area vulnerable to storm surge and landslides. Public hurricane shelters tend to be utilized by the most vulnerable, those who lack the economic means for other evacuation options, and populations with underlying health conditions that place them at higher risk for pandemic complications. One of the most vulnerable populations in evacuating for weather-related disasters is older adults (Brunkard et al., 201337). In addition to the decreasing physical and cognitive abilities that are a characteristic of aging, around 85% of older adults have chronic health conditions that make evacuating more complicated (National Institute on Aging, 201738). Various studies support the conclusion that racial and ethnic minorities are at greater risk during pandemics (Kirby, 202039; Tai et al., 202140). In many cases, they often have less capacity to implement preparedness strategies or tolerate its impact given disparities in underlying health status and social factors, such as socio-economic disadvantages; cultural, educational, and linguistic barriers; and lack of access to health care and transportation (Hutchins et al., 200941).

Methods

Research Questions

The purpose of the research conducted in the PRVI region is to further understand public perceptions of the compounding risks posed by hurricanes, landslides, storm surge, and a pandemic, and to examine the extent to which people risk their lives by sheltering in place rather than evacuating. The research questions addressed in this study include:

- How does peoples’ risk perception of existing hazards associated with hurricanes and preparedness planning differ by gender, location, type of housing, political affiliation, economic earnings, level of education, transportation options, and access to a generator during the pandemic?

- What percentage of people plan to evacuate due to a hurricane event during the COVID-19 pandemic? What factors influence their evacuation behavior, and will they instead choose to shelter in place despite a recommendation to evacuate to a safer location or a government-operated shelter staffed by local authorities?

- What are the perceived barriers and facilitators that trigger action decision-making under threat of a hurricane during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Are individuals likely to utilize public shelters? Do people view public shelters as excessively risky due to concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic?

- What are the most relied on sources of information during a hurricane to reach residents in the PRVI region?

COVID-19 poses a unique threat to transportation and sheltering considerations during hurricane evacuations (Collins et al., 202142; Hill et al., 202143; Shultz et al., 202044). Prior research has not been conducted in the PRVI region into an individual’s risk perception of natural hazards while considering evacuating from a hurricane during a pandemic. Officials also need to understand how evacuation plans change with COVID-19-encouraged social and physical distancing, which directly conflicts with the movement and congregation seen in hurricane evacuations. The results can be compared between studies of different islands and existing studies on the mainland to examine which policies and practices are best suited for each location.

Study Site Description

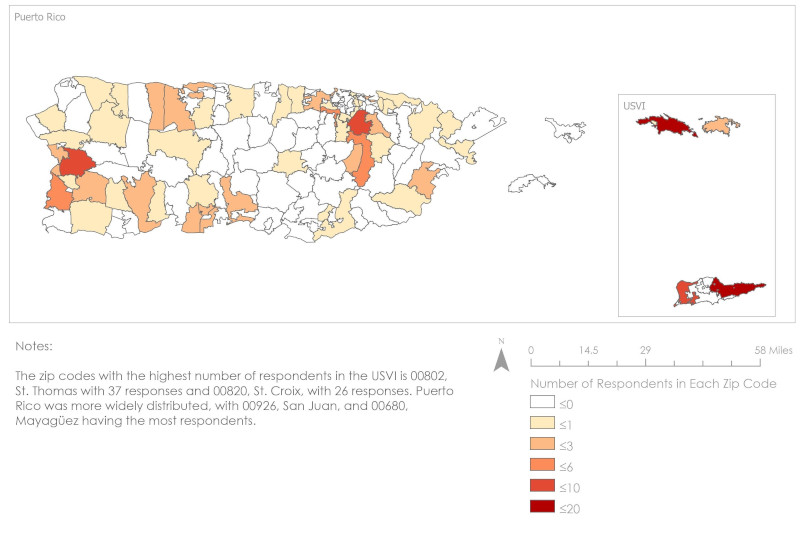

The survey was disseminated within the U.S. territories of the PRVI region. The study sample represented more than 120 zip codes spread across three primary islands in the USVI (St. Croix, St. John, and St. Thomas) and 71 municipalities in PR (see Figure 1). Access to this large geographical study site was gained by utilizing varied research and professional networks within the territories, who then furthered dissemination of the digital link to their networks.

Figure 1. Preliminary Map (as of January 1, 2021) of Respondents by Zip Code

Data, Methods, and Procedures

In June 2020, a separate online survey (in both English and Spanish) of 40 questions was disseminated to Florida residents, with 7,102 people responding from more than 50 of the 67 counties in Florida. Collins et al. (2021) found that approximately 74.3% of individuals viewed the risk of being in a shelter during the COVID-19 pandemic as more dangerous than enduring hurricane hazards. In September 2020, Collins and her team were funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to understand evacuation decision-making and behavior related to Hurricanes Laura and Sally during the global pandemic. This initial research, conducted outside of the scope of this grant, by Collins et al. (2021) has informed the development of the survey focused on the U.S. territories. Several meetings involving the research team members and community stakeholders were organized through virtual sessions to further develop and design a pre- and post-hurricane survey instrument. A strong emphasis was placed on collecting information that would be useful for practitioners in the PRVI region managing the COVID-19 pandemic, and responsible for coordinating response to hurricanes as well.

Survey instruments developed by the research team were available in English, Spanish, or French Creole (about 8.6% of the USVI population are French Creole, also known as Patois). Prior to dissemination, each instrument was pilot tested by native speakers of the target languages with the Spanish and French Creole survey instruments being administered to persons fluent in English as well. This was done to test equivalence of translated instruments and determine a consensus on alternative wording. In general, the questions performed well regarding participants’ understanding of the questions, perceived clarity, the accuracy of the translation, structure of the questions, and the technology used, with only minor changes needing to be made with the survey instrument. A draft survey instrument was circulated for comment among subject matter experts from communications, emergency management, public health, and geosciences. After further revisions, the survey instruments were submitted to the Ponce Health Sciences Human Research Protection Program, where it was deemed exempt from the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

A digital survey was administered in the PRVI region as a pre-hurricane assessment. This survey collected information regarding risk perception of evacuation and public sheltering during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey instrument, consisting of approximately 70 questions, included questions on demographics, characteristics of their home (i.e., located in a physically vulnerable area, year built), special needs shelter use, and pre-existing health conditions. The survey also included various Likert-scale questions that assess an individual’s perception of risk regarding sheltering-in-place versus evacuating or staying at home when considering compound hazards. In 2021, a second pre-hurricane survey was disseminated to participants from PRVI that considers whether people are vaccinated and if that affects their intended evacuation behavior. This survey is currently active, and the sample may or may not include those who participated in the first survey.

Sample Size and Participants

Sample Selection and Recruitment

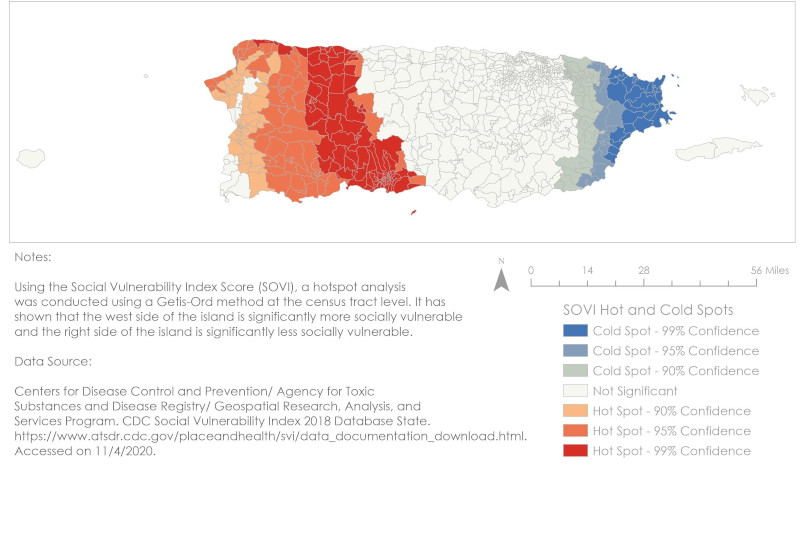

All residents of PR and the USVI were included in the target sample criteria as the whole region is affected by hurricanes and is at risk for a hurricane evacuation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were excluded if they were under the age of 18 or did not reside in the PRVI region. Barring these measures, no other exclusionary or inclusionary criteria were utilized. The samples were obtained through convenience sampling utilizing an extensive network of personal and professional connections in PR and the USVI. The Co-PIs on this project, in addition to their extensive network, represented agencies such as the Puerto Rico Science, Technology, and Research Trust, the Virgin Islands Territorial Emergency Management Agency (VITEMA), Puerto Rico Emergency Management Agency (PREMA), University of the Virgin Islands, University of Puerto Rico, the Caribbean Exploratory Research Center, and the Virgin Islands Department of Health, among others. Additionally, connections were made by these professional contacts to distribute to trusted community members, local news stations, and social media to catch a wide variety of respondents. After initial data were collected, target areas on the western side of PR and the southern islands of the USVI were identified due to low initial response rate and higher social vulnerability (see Figure 2). Further targeted Facebook advertisements were placed to ensure more exposure in this region. Regarding recruitment via a social media approach, approximately 17,000 people viewed Facebook advertisements that targeted geographic areas needing an increased response (see Figure 3). Due to these targeted advertisements, there was an increased digital response to the survey, especially in the areas that were prioritized during the campaign.

Figure 2. Puerto Rico Hotspot Analysis of Social Vulnerability for Survey Sampling

Figure 3. Example of Recruitment Advertisements on Facebook

Sample Demographics

In total, 457 unique survey respondents participated in this study. Three hundred twenty-one of the surveys were completed in Spanish, and the remaining 136 were completed in English. Three hundred fifty-three respondents were from PR, and 95 were from USVI (an additional six identified as residing elsewhere and thus were not included in the further analysis). The average age of the sample is 54.84 (SD = 12.79), with a range of 21 to 91 years of age. The sample consisted of a majority of female respondents (76.4%). Approximately half identified as Hispanic or Latinx (47.4%), with the remaining respondents being distributed among other racial categories. Approximately two-thirds (66.2%) of the sample had earned a college degree. The average size of a respondent’s household was 2.61 (SD = 1.32) persons, with 35.6% of all households sampled including someone over the age of 65. On average, respondents made approximately $50,000-$59,999 for their annual household income; however, 28.1% did identify that they made less than $20,000 a year. Only half of the sample (48.9%) identified that they were employed full-time. Review Table 1 for further individual level respondent characteristics across the PRVI region.

Data Analyses

Data were cleaned and organized logically from their original Qualtrics output. After these procedures, data were analyzed using the IBM statistical software program SPSS v. 26. Additional mapping was produced using ArcGIS Pro. Due to many of the questions featured in the survey being categorical or ordinal in nature, analytical techniques consisted of nonparametric testing, including chi-square tests, McNemar’s tests, and Spearman’s rho. Where logical, t-tests and ANOVAs were also performed. Any free response boxes, such as “other” hazards, health conditions, etc., were cleaned and categorized for basic qualitative analysis.

Researcher Positionality, Reciprocity, and Other Ethical Considerations

Researchers need to be particularly mindful of their positionality and ensure the reciprocity of established relationships when conducting research (Secules et al., 202145). Ethical considerations must permeate the conceptualization and design of the study as well as during data analyses and the dissemination of findings in a timely manner. Ethical and participatory research requires a shared space for dialog, positive feedback, and constant reflection throughout the research process. The aim was to engage practitioners and academics from early on in the process to include expertise from public health, epidemiology, emergency management, geosciences, meteorology, marketing, and communications. This helped to not only build trust but develop a research agenda that is mutually defined while ensuring that some members of the research team are stakeholders from the target communities represented in this study. The research team paid close attention to the design of the survey instruments, data collection methods, and analyses. Everyone on the research team was engaged in reviewing existing literature, the grant writing process, research design, survey development, testing of the survey instrument, dissemination, and logistics (Oulahen, 202046). Understanding political, institutional, social, and cultural dynamics through initial meetings with the research team and stakeholders from across the PRVI region provided further insight through these processes. Each team member provided insights into identifying strategies to ensure data collection was ethical, equitable, and effective across all demographics and geographic locations. Throughout the data collection process, the team monitored where responses were generated to determine recruitment strategies relevant for those particular areas of the islands—utilizing mapping tools to identify social vulnerability, engaging local leaders and agencies operating in target areas, and drawing on local knowledge and social networks to reach those at high risk of complications due to compounding threats. Bilingual speakers on the team assisted in cleaning data, translating, and coding processes across all languages.

Findings

Results and Discussion of Findings

Risk Perception and Preparedness Planning (RQ1)

The majority of the sample self-identified that they did not live in an area that is typically advised to evacuate during a hurricane (72.1%) or in an area that has experienced flooding during past hurricanes (70.0%). When looking at homeownership and the built environment, 70.8% of respondents were homeowners and 23.2% were renters. When asked how concerned they were about general hurricane hazards at their residence, 27.4% said “extremely concerned,” 19.3% said “very concerned,” 23.0% said “concerned,” 20.1% said “somewhat concerned,” and 10.2% said “not concerned.” This was further explored by asking how concerned individuals were on a five-point scale ranging from “extremely concerned” to “not concerned” about a wide range of hurricane-specific hazards. The factors that sparked the most concern were the intensity/category of the storm (M = 3.13, SD = 1.10), the wind speed (differentiated from wind gusts) (M = 2.98, SD = 1.13), and size of the storm (M = 2.82, SD = 1.21). Of least concern to the participants were storm surge (M = 1.08, SD = 1.44), tornadoes (M = 1.58 SD = 1.49), landslides (M = 1.62, SD = 1.46), and tsunamis (M = 1.53, SD = 1.59).

When asked to list any additional concerns or hazards in the area of their residence, 41% of respondents identified a water hazard, and 14.4% identified landslides. Breaking down those who identified water hazards further, 43.9% identified concerns about an inland body of water with 31.6% concerned about coastal waters and 12.3% concerned about general flooding.

Many respondents identified that they had disaster kits ready (77.1%) and 69.1% of the sample owned generators, but approximately half (45.9%) identified that they did not have a hurricane evacuation plan. It was found that individuals residing in Puerto Rico were more likely to have a hurricane plan than their counterparts in the USVI (X2(2) = 8.737, p = .013). Additionally, the likelihood of having a hurricane plan increased with a respondent's education level (X2(8) = 15.562, p = .049). In fact, no individuals that identified they had less than a high school education had a hurricane plan; this number increases to more than half of respondents (50%-61%) for those with a high school degree or higher. Interestingly, disaster kits were also more likely to be owned by individuals with a lower household income (ranging from less than $20,000 to $99,999) than their richer counterparts (those earning between $100,000 and greater than $150,000), X2(4) = 15.308, p = .004. Out of those who did own a generator, 37.2% said that owning one influenced their evacuation decisions.

Evacuation Decision-Making (RQ2)

When asked about their predicted evacuation response if their island was threatened by a severe hurricane, only 20.4% stated that they would evacuate the island. Another 59.4% stated that they would not evacuate, and an additional 20.2% stated that they did not know what they would do (Table 3). Individuals in Puerto Rico were more likely to state that they wouldn’t evacuate (60.3%) than their counterparts in the USVI (56.1%). Additionally, when asked if they would utilize a public shelter during the 2020 hurricane season, only 14.2% of respondents definitely or probably felt that they would. When asked if they were capable and could evacuate if a hurricane were to impact their area in their present situation, 41.8% said they could, 27.3% said that they could not, 10.2% said maybe, and 20.7% said that they did not know. When asked the question, “How likely is it that you and members of your household will evacuate for the next hurricane that is expected to have a major impact on your area?” only 15.7% stated that this was “very likely,” 44.1% stated that this is “somewhat likely,” and 40.3% stated that this is “not at all likely.”

For alternate shelter options, the majority of individuals (81.9%) identified that they would stay with family, friends, or a potential combination of the two in the case of a hurricane season as a means of alternative shelter. Of those residing in PR, 52.6% could find alternate shelter from a friend or family member residing in their municipality, 68.8% outside of their municipality, and 60.6% outside of PR. In USVI, 53.2% stated that they could find shelter from a family or friend on their island, 22.1% on another island, and 68.8% outside of the USVI.

Regarding future evacuation expectations, many individuals found that the phrasing of emergency management communications was critical. When asked if they were to be ordered to evacuate for a storm instead of advised, 64.4% agreed that they would be “more likely to evacuate than stay at home.” Notably, 11.3% of the sample has been advised in the past to evacuate for a tropical storm or hurricane. Out of this percentage, approximately half evacuated when they were recommended to (52.1%).

Facilitators and Barriers to Hurricane Evacuation During COVID-19 (RQ3)

When asked what would make it easier to evacuate, the two most common responses were access to transportation to a shelter or outside of the area of effect (14.3% of responses) and better communications on shelter and evacuation information, especially if that included COVID-19 specific information (20.1%) (Table 4). Other notable comments include having access to resources and places to evacuate to, having a safe shelter or family home, and for shelters to have adequate resources. For example, 24.6% of the sample stated that it was very difficult to leave their home if they needed to evacuate themselves and household members. Approximately half stated that this would be “somewhat difficult” of a task (47.4%), and 28.0% found it to be “not difficult at all.” When asked about their barriers to evacuation, many addressed a lack of information on the evacuation process or shelters (14.4%), limits with their transportation (11.5%), and limitations with their pets (14.8%) (Table 4). This is corroborated by those who identified as having a pet (62.0%); among this group, 66.1% identified that their pets influence their evacuation. Other notable barriers to evacuation include limitations by their household members, poor shelter conditions, uncertainty in their evacuation decisions, and terrain-related barriers (such as poor road conditions or landslides making areas inaccessible). Of note is that very few (0.8%) identified COVID-19 as a barrier to evacuating, signaling that individuals may not be as cautious about contracting the virus in light of an emerging crisis such as a hurricane. Based on survey results, 14.1% of respondents would require assistance with transportation to leave an evacuation area, with an additional 8.1% unsure if they would need help evacuating. Most people (87.6%) would rely on personal transportation to get them to a safer place during an evacuation.

Public Shelter Perceptions (RQ4)

Individuals’ likelihood of utilizing public shelters has decreased in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. When respondents were presented with the statement, “Prior to COVID-19, if I needed to evacuate to a shelter during the 2020 hurricane season, I would most likely have gone to a shelter,” 8.9% found this to be “definitely true,” 23.9% found this to be “probably true,” 25.4% found this to be “probably false,” and 41.8% found this to be “definitely false.” When posed the statement, “Considering the current situation with COVID-19, I would still go to a shelter if I needed to during a hurricane evacuation advisory in 2020,” 4.1% found this to be “definitely true,” 10.1% “probably true,” 32.2% “probably false,” and 53.6% “definitely false.”

A McNemar’s test was used to determine if the decision to go to public shelters was affected in any way by COVID-19. Grouping was done to produce dichotomous responses by combining responses that found the statements to be true or false (both definitely and probably) into one category. The results of this test showed statistical significance between an individual’s decision to use a public shelter before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, p < .001. This reflects that public shelter usage has the potential to decrease when the decision is coupled with COVID-19 threats.

Individuals are additionally more likely to have a negative shelter perception, with 51.5% answering “definitely true,” 35.2% “probably true,” 6.1% “probably false,” and 7.3% “definitely false” when presented with the statement, “If my only option was to evacuate to a shelter in my area, I would rather shelter-in-place than risk being exposed to the potentially large group inside a shelter.” There was a significant difference between the territories regarding responses to this question (X2(1) = 5.727, p = .017); individuals from the USVI were statistically more likely to answer “true” to this statement. This indicates that those residing in the USVI may be more apprehensive and less trusting of their shelters as they would rather shelter-in-place to avoid COVID-19 risks. When presented with, “If I was advised to leave my house during a hurricane evacuation, I think the risks of being in a disaster shelter during the COVID-19 pandemic would be worse than staying at home and enduring the risks of a hurricane,” 40.9% found it to be “definitely true,” 34.8% “probably true,” 15.8% “probably false,” and 8.5% “definitely false.” Individuals who viewed this statement as true rated social networking higher as a source of information they relied upon during a hurricane (t(113.525) = 2.046, p = .043).

Additionally, individuals did not have much trust in shelters’ ability to maintain social distancing, with 13.8% answering “definitely true,” 37.2% “probably true,” 27.0% “probably false,” and 22.0% “definitely false” when presented with the statement “I think if I went to a disaster shelter during a hurricane, the authorities will have adequate safeguards in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the facility, such as being able to social distance at least 6ft. in place.” The results to this question were found to be significantly different between men and women (X2(1) = 6.197, p = .013), with women more likely to answer “false” to this statement, indicating an increased distrust in authorities to protect them. A difference was also found on the political spectrum (X2(6) = 26.853, p < .001). Those who identified as “very conservative” or “conservative” were more likely to agree with this statement (72% and 64%, respectively), while “moderates” (58%), “liberals” (37.5%) and “very liberal” individuals (50.0%) were less likely to agree in comparison to their “conservative” counterparts. The Likert-scale response results presented in this section are summarized in Table 5.

Sources of Information (RQ5)

Questions addressing their most relied upon sources of information during a hurricane were also presented with a Likert-type response option. Overall, the most relied-on information sources were the national media, electronic media, and radio broadcasts. Whereas the least relied on were print media, social networking (e.g., Facebook), and friends a distance away from the respondent (see Table 6). However, when comparing the results of the question, “How likely is it that you and members of your household will evacuate for the next hurricane that is expected to have a major impact on your area?” to sources of information most relied on by the three groups (those who were very, somewhat, and not at all likely to evacuate), it was found that there was a significant difference in reliability ranking between them regarding friends, both those nearby (X2(8) = 28.936, p < .001) and those a distance away (X2(8) = 21.506, p = .006), as an information source. For both of these information sources (friends near and far away), those who replied “somewhat likely” had the highest mean rating for communication from a friend on their reliance during a hurricane; this is then followed by those who answered “very likely” and then finally those who answered “not at all likely.”

COVID-19 and Health (RQ1, RQ2, RQ3)

When this 2020 survey was conducted, 57.5% of respondents were under stay-at-home conditions and 13.1% had limited business restrictions. One thing to keep in mind, vaccines were not yet available when this first PRVI survey instrument was deployed. More than half of the sample considered themselves at greater risk for COVID-19 illness due to existing health risks (56.4%). Of those surveyed, 91.0% of respondents said they would be able to provide a mask for all family members evacuating with them if they went to a shelter. Additionally, it was found that there was no significant difference between evacuation decision (an individuals’ likelihood to evacuate and their predicted evacuation behavior) and their self-identified health status, indicating that health conditions did not play a role in the decision to evacuate or stay at home.

Conclusions

Key Findings

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound effect on how people make their decisions to evacuate. More than half of the sample considered themselves vulnerable to COVID-19. When asked about their actions in the 2020 hurricane season, individuals who would have previously evacuated to a shelter would choose not to during the pandemic, reflecting that public shelter usage has the potential to decrease when the decision is coupled with COVID-19 threats. Additionally, individuals were shown to have a negative perception of public shelter options, with approximately half of the respondents having little faith in shelters’ ability to maintain social distancing and other preventative actions. Additionally, more than half the sample stated that they would “definitely” shelter-in-place to minimize exposure to large groups in the shelter, and 75.5% of the sample thought that the risks of being in a shelter were higher than those that they would have to endure if they were to stay home during a hurricane. These results are comparable to the responses seen in Florida, where 74.3% of individuals felt shelters were riskier than their homes during these compounding hazards and that more than half agreed that they would aim to shelter-in-place rather than risk exposure (Collins et al., 2021).

Public shelters are typically used by those who do not have economic means and are part of the most vulnerable segments of our population. Due to the compounding hazards presented during the COVID-19 pandemic, utilization of these shelters would decrease, causing potentially harmful and dangerous scenarios for those who both feel uncomfortable with large group gatherings at shelters and lack the means to enact an alternate evacuation plan.

The majority of the sample (59.4%) would not evacuate for an impending severe hurricane and only 14.2% would utilize a public shelter. This is drastically different from decision-making on evacuation revealed by prior research in the PRVI region. Morrow & Gladwin (2014a, 2014b) found that 68% of Puerto Rico residents and 61% of residents in the USVI would evacuate for a major storm and that 22% of people in Puerto Rico and 29% of people in the USVI would utilize public sheltering. This change may indicate the vast difference that COVID-19 can play on evacuation decision-making during a hurricane event. Fortunately, many individuals did identify that they had taken protective actions at their households, including preparing disaster kits, owning generators, and having hurricane evacuation plans established with their families. Additionally, 41.8% did identify that they think they would be able to evacuate in the future, displaying that many individuals, despite choosing to stay at home, could likely evacuate if absolutely necessary. The most commonly mentioned aids to evacuation were increased options for transportation to shelters and better communication of shelter and evacuation information. Understanding geographic location in relation to evacuation decisions will allow public health preparedness planners to identify municipalities in those areas with the highest need.

Almost a quarter of respondents stated that they would have found it very difficult to evacuate their households if needed, showing some potential room for improvement in ensuring equitable hurricane preparedness for all. The most commonly mentioned barriers to evacuation were a lack of easily obtained evacuation and shelter information, and limitations regarding transportation and pets. Potential communication methods should focus on national media, electronic media, and radio as these were the most relied upon sources of information used by survey respondents during a hurricane. Additionally, communications should continue to emphasize that the intensity of a storm is not the only predictor of its risk and emphasize the risks of water-based hazards, which have historically posed the largest threat to loss of life, as it was shown that survey participants ranked intensity as their top hurricane concern while also placing storm surge in last.

Implications for Public Health Practice

This study adds to the existing body of knowledge on this subject and benefits emergency planners by providing information that could benefit their efforts of communicating risk and targeted messaging to their constituents. COVID-19 poses a unique threat to mass care operations, including congregate sheltering, compared to other infectious diseases during prior hurricane evacuations. Emergency managers and public health planners—including government officials, private sector, and nonprofit organizations—need to understand how hurricane evacuation plans change with compounding hazards, including flooding and pandemics, to analyze various scenarios and evaluate existing strategies. Furthermore, there is a need to integrate the social determinants of health into disaster planning with a focus on improving quality-of-life outcomes and reducing risk by taking into consideration safe housing, transportation, economic stability, social and community support, and effective communication (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], n.d.47). The COVID-19 pandemic has provided emergency management and public health officials a unique opportunity to work together more closely, providing an interdisciplinary approach to promote health equity by mitigating adverse health consequences during a hurricane-pandemic threat.

Social cues during the response phase, including seeing neighbors evacuate, receiving messages from family and friends or local authorities, and seeing protective actions from local government and businesses influence evacuation decision-making (Freeman et al., 202148). Families, friends, and employers should be encouraged by emergency management and public health officials to share alerts and warning messages from local authorities including evacuation guidance and mitigation measures to limit exposures to COVID-19. Local authorities should address concerns and doubts about the safety of congregate shelters as a viable option to seek refuge during a disaster. The most relied-on information sources were the radio broadcasts, national media, and electronic media (television, internet, video streaming, text messaging/SMS). Using these mediums to share updated shelter plans and actions taken by planners to mitigate the spread of the virus, like reducing shelter capacity to support social distancing and heightened cleaning measures to disinfect high-touch points, helps to inform residents (CDC, 202149). Communicating these plans to maintain public safety is necessary for building trust and positively influencing people to evacuate to a shelter if no other options are available to them. However, involving the local community in the planning process to mitigate risk and provide feedback throughout the process addresses many concerns that may be a barrier to the decision-making process (Arlikatti et al., 201850).

Strengthening our understanding of perceived barriers to evacuation decisions allows for public health interventions designed to increase self-efficacy and support cues to action. During the response, issuing mandatory evacuation orders significantly increased evacuation rates (Freeman et al., 2021). It is important to lead by example and engage residents visibly in the actions that you want your community to adopt—for example, sharing images of people preparing for the potential threat of a hurricane, evacuating to a local emergency evacuation shelter, or showcasing infection control measures being implemented increases self-efficacy by giving residents a sense of what is required to successfully perform these behaviors.

Formative research supports the social marketing planning process to determine the appropriate communication channels and messages to influence behavior change regarding evacuations. Emergency messaging is key to action. Respondents mentioned that, if they needed to prepare for a hurricane, one barrier to evacuating would be a lack of communication regarding evacuations and sheltering that included information specific to COVID-19. Effective communication for emergency preparedness requires complete and clear information that people can easily understand and act upon to ensure they are making the right decision for their household (ODPHP, n.d.). Public safety officials in collaboration with communications experts in both Puerto Rico and the USVI could develop risk communication messages prior to the threat of a hurricane event that is designed to motivate individuals and their communities to take appropriate protective actions in a timely manner whether that decision is to evacuate or shelter-in-place.

Information and messages regarding natural hazards are often overly complex and difficult to conceptualize the potential effects that could occur. Preparedness education requires developing multi-media campaigns to build trust among different audiences to help people make informed decisions that can improve adverse outcomes, especially for marginalized groups with high social vulnerability. Local organizations and government agencies can promote preparedness and mitigation through effective communication strategies—for example, by using social marketing to develop targeted messaging to populations that have the highest return on investment and test out communication strategies to ensure they are clear, complete, and actionable through the most appropriate medium (ODPHP, n.d.).

Findings help guide existing plans across the PRVI region based on intended future actions of residents if confronted with a hurricane of major impact while providing knowledge of potential barriers, concerns, and misconceptions that may exist due to the pandemic. Understanding potential needs for emergency sheltering and transportation during the response along with public health services helps forecast future staffing needs and identify gaps in an already fatigued workforce due to the pandemic. Adaptation to build the capacity of communities and local governments needs to occur at the community level (Keim, 200851). Additional questions may provide insight into alternatives to public sheltering that were employed following Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017. Involving culturally diverse and vulnerable populations in evacuation and decision-making assessments ensures protective actions are designed for individuals and communities to realistically operationalize mitigation capabilities when needing to evacuate during the threat of a natural disaster during the pandemic (Arlikatti et al., 2018).

Dissemination of Findings

The results from this research have been disseminated as a preliminary report to all interested stakeholders in the PRVI region. This report and other key research products are hosted on DesignSafe-CI, a project-sharing software hosted by the Natural Hazards Engineering Research Infrastructure (NHERI) specializing in disaster research. Stakeholders will also receive the link to this finalized report when published on the Natural Hazards Center webpage. Additionally, the research team will present this research at local and national conferences, including the Natural Hazards Center 2021 Workshop. Additional dissemination will occur through the PR Public Health Trust and Hurricane Hub, who have two available communications professionals on staff that can support dissemination of press releases to media outlets and through other digital avenues. Additionally, in collaboration with the PR Science, Technology, and Research Trust, we can create a landing page to highlight this project that will be further utilized as a dissemination tool. Finally, we will be submitting this work to the American Meteorological Society journal Weather, Climate, and Society, and when published we will provide a link in the acknowledgements to the Natural Hazards Center as the funding source and a link to this preliminary report.

Limitations

Generalization of results may not be applicable to the entire population of PR and the USVI due to its differing nature to the census results from this region. The sample featured in this research has an underrepresentation of USVI (21.1%) compared to PR (78.8%). Additionally, the sample is differing from the 2019 PR population estimates (U.S. Census Bureau, 201952), specifically regarding the high percentage of female respondents (76.4% compared to the 2019 estimate of 52.5%), older age (M = 54.84, SD = 12.79; 2019 estimates predict only 21.3% of the population is 65 years of age or older), higher socioeconomic status (with the sample identifying a median income between $50,000 and $59,999 while the median household income reported in the 2019 estimates was $20,539), and more diverse racial sample (with only 47.4% of the sample identifying as Hispanic or Latinx compared to 98.7% in the 2019 census estimates). Additionally, since PR is overrepresented in this sample, the USVI could have unique differences not well captured through the initial sample obtained in this study. As of 2010, the Creole-speaking population in USVI was 8.6% of the population; 2.6% of the population who speak Creole have an English-speaking proficiency that is less than “very well” (U.S. Census Bureau, 201053). Although this survey was available in French Creole and some connections were established with this community, we had no respondents. As such, this population in the USVI is underrepresented in this sample. These discrepancies could be due to the digital format that the survey was presented in, as those without access to necessary technology or internet (such as those from a lower socioeconomic status) would not be able to take the survey. Due to the complicated nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated university closures, it was not possible to supplement the study with in-person interviews as planned for the initial survey.

Future Research Directions

Additional analyses will be generated from the wealth of data gathered from this survey. For example, conducting geospatial and hotspot analysis can provide some indication of where people are most likely to evacuate. Determining and prioritizing locations where there is a need for congregate shelters provides an opportunity to reduce the number of shelters in areas with little need while identifying facilities in close proximity to demand. Further analysis comparing the Florida survey data (Collins et al., 2021) and the two subsequent PRVI surveys will be conducted to see if there were differences in evacuation and sheltering responses and risk perception of residents for Florida, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Due to funds being available for the in-person data collection that went unused from the first survey, these funds were redirected to a second survey that was created and disseminated prior to the start of the 2021 hurricane season in the PRVI region. These data will create a timeline of changes in attitudes on evacuations and COVID-19 as we are further into the pandemic. Additionally, this 2021 season survey collects information on an individual’s vaccination status and how that would affect their decision to evacuate. Future work, when in-person field work is possible, could capture data from a more representative sample focusing on those without access to technology or the internet. If a hurricane results in a large evacuation, a third survey was designed from this project to capture actual evacuation behavior rather than intended evacuation behavior which was the focus of the 2020 and 2021 surveys that were administered. To ensure that these future surveys capture the Creole population in the USVI, which was previously inaccessible, we will consider sending in-person interviewers to Creole neighborhoods as well as sending the electronic survey link to teachers of Creole language, schools that have a large percentage of Creole-speaking families, and Creole community and religious leaders.

Acknowledgements. We would like to acknowledge our extensive stakeholder team for their efforts in survey question feedback, testing, and distribution. We would also like to thank all our translators, with special acknowledgement of Louiseul Azor for assisting with the Creole translation. Additionally, we acknowledge the work of Killian McSweeney for his assistance with references.

References

-

Klotzbach, P. J., Bell, M. M., Jhordanne, J., & Gray, W. M. (2020). Forecast of Atlantic seasonal hurricane activity and landfall strike probability for 2020. Colorado State University. ↩

-

Klotzbach, P. J., Bell, M. M., & Jhordanne, J. (2021). Extended range forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and landfall strike probability for 2021. Colorado State University. Retrieved 2021, April 15, from https://tropical.colostate.edu/Forecast/2021-04.pdf ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2011, December). A whole community approach to emergency management: Principles, themes, and pathways for action (FDOC 104-008-1). U.S. Department of Homeland Security. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1813-25045-0649/whole_community_dec2011__2_.pdf ↩

-

Burger, J., & Gochfeld, M. (2020). Involving community members in preparedness and resiliency involves bi-directional and iterative communication and actions: a case study of vulnerable populations in New Jersey following Superstorm Sandy. Journal of Risk Research, 23(4), 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2019.1593221 ↩

-

Jury, M. R. (2018). Puerto Rico sea level trend in regional context. Ocean and Coastal Management, 163, 478–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.08.006 ↩

-

Vitousek, S., Barnard, P. L., Fletcher, C. H., Frazer, N., Erikson, L., & Storlazzi, C. D. (2017). Doubling of coastal flooding frequency within decades due to sea-level rise. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1399. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01362-7 ↩

-

Elsner, J. B., Kara, A. B., & Owens, M. A. (1999). Fluctuations in north Atlantic hurricane frequency. Journal of Climate, 12(2), 427–437, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1999)012<0427:FINAHF>2.0.CO;2 ↩

-

Elsner, J. B., Jagger, T. H., & Niu, X., (2000). Shifts in the rates of major hurricane activity over the North Atlantic during the 20th century. Geophysical Research Letters, 27(12), 1743–1746. ↩

-

Jury, M. R., Rios-Berrios, R., & García, E. (2012). Caribbean hurricanes: Changes of intensity and track prediction. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 107, 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-011-0461-5 ↩

-

Jury, M. R., Chiao, S., & Raphael, C. (2019). The intensification of hurricane Maria 2017 in the Antilles. Atmosphere, 10(10), 590–612. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10100590 ↩

-

Cox, D., Arikawa, T., Barbosa, A., Guannel, G., Inazu, D., Kennedy, A., Li, Y., Mori, N., Perry, K., Prevatt, D., Roueche, D., Shimozono, T., Simpson, C., Shimakawa, E., Shimura, T., & Slocum, R. (2019). Hurricanes Irma and Maria post-event survey in U.S. Virgin Islands. Coastal Engineering Journal, 61(2), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/21664250.2018.1558920 ↩

-

Wang, G., Kearns, T. J., Yu, J., & Sanchez, G. (2014). A stable reference frame for landslide monitoring using GPS in the Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands region. Landslides, 11, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-013-0428-y ↩

-

Bessette-Kirton, E. K., Cerovski-Darriau, C., Schulz, W. H., Coe, J. A., Kean, J. W., Godt, J. W., Thomas, M. A., & Hughes, K. S. (2019, June). Landslides triggered by Hurricane Maria—Assessment of an extreme event in Puerto Rico. GSA Today, 29(6), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1130/GSATG383A.1 ↩

-

Peters, J. W. (2017). In the Virgin Islands, Hurricane Maria drowned what Irma didn’t destroy. New York Times. Retrieved 2020, September 25, from at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/27/us/hurricane-maria-virgin-islands.html ↩

-

Baker, E. J. (1991). Hurricane evacuation behavior. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 9, 287–310. http://ijmed.org/articles/412/ ↩

-

Baker, E. J. (1995). Public response to hurricane probability forecasts. The Professional Geographer, 47, 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1995.00137.x ↩

-

Gladwin, C., Gladwin, H., & Peacock, W. (2001). Modeling hurricane evacuation decisions with ethnographic methods. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 19(2), 117–143. http://www.ijmed.org/articles/479 ↩

-

Whitehead, J. C., Edwards, B., van Willigne, M., Maiolo, J. R., Wilson, K., & Smith. K. T. (2000). Heading for higher ground: Factors affecting real and hypothetical hurricane evacuation behavior. Global Environmental Change Part B: Environmental Hazards, 2(4), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1464-2867(01)00013-4 ↩

-

Dow, K., & Cutter, S. L. (2000). Public orders and personal opinions: Household strategies for hurricane risk assessment. Global Environmental Change, 2(4), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1464-2867(01)00014-6 ↩

-

Eisenman, D. P., Cordasco, K. M., Asch, S., Golden, J. F., & Glik, D. (2007). Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), S109–S115. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.084335 ↩

-

Elder, K., Xirasagar, S., Miller, N., Bowen, S. A., Glover, S., & Piper, C. (2007). African Americans’ decisions not to evacuate New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina: A qualitative study. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), S124–S129. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.100867 ↩

-

Miller, L. M. (2007). Collective disaster responses to Katrina and Rita: Exploring therapeutic community, social capital, and social control. Journal of Rural Social Sciences, 22(2), 45–63. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jrss/vol22/iss2/4 ↩

-

Moore, S., Daniel, M., Linnan, L., Campbell, M., Benedict, S., & Meier, A. (2004). After Hurricane Floyd passed: Investigating the social determinants of disaster preparedness and recovery. Family and Community Health, 27(3), 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003727-200407000-00007 ↩

-

Collins, J. M., Ersing, R. L., & Polen, A. (2017). Evacuation decision making during Hurricane Matthew: An assessment of the effects of social connections. Weather, Climate, and Society, 9(4), 769–776, https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-17-0047.1 ↩

-

Collins, J. M., Ersing, R. L., Polen, A., Saunders, M., & Senkbeil, J. (2018). The effects of social connections on evacuation decision making during Hurricane Irma. Weather, Climate, and Society, 10(3), 459–469. https://doi.org/0.1175/WCAS-D-17-0119.1 ↩

-

Morss, R. E., Demuth, J. L., Lazo, J. K., Dickinson, K., Lazrus, H., & Morrow, B. H. (2016). Understanding public hurricane evacuation decisions and responses to forecast warning messages. Weather and Forecasting, 31(2), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1175/WAF-D-15-0066.1 ↩

-

Senkbeil, J., Collins, J. M., & Reed, J. (2019). Evacuee perception of geophysical hazards for Hurricane Irma. Weather, Climate, and Society, 11(1), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-180019.1 ↩

-

Sherman-Morris, K., Senkbeil, J., & Carver, R. (2011). Who’s Googling what? What internet searches reveal about hurricane information seeking. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 92(8), 975–985. https://doi.org/10.1175/2011BAMS3053.1 ↩

-

Morrow, B., & Gladwin, H. (2014a). U.S. Virgin Islands hurricane evacuation study behavioral analysis. Federal Emergency Management Agency, National Planning Center of Expertise for Coastal Storm Risk Management, National Hurricane Program Office. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4247.2963 ↩

-

Morrow, B., & Gladwin, H. (2014b). Puerto Rico hurricane evacuation study behavioral analysis. Federal Emergency Management Agency, National Planning Center of Expertise for Coastal Storm Risk Management, National Hurricane Program Office. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1909.5049 ↩

-

Shultz, J.M, Kossin, J., Shepherd, M., Ransdell, J., Walsh, R., Kelman, I., & Galea, S. (2019). Risks, health consequences, and response challenges for small-island-based populations: Observations from the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 13(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2018.28 ↩

-

Buckle, P. (2006). Assessing social resilience. In D. Paxton & D. Johnston (Eds.), Disaster Resilience: An Integrated Approach (pp. 88–104). Charles C. Thomas Publishers ↩

-

Demuth, J. L., Morss, R. E., Morrow, B. H., & Lazo, J. K. (2012). Creation and communication of hurricane risk information. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 93(8), 1133–1145. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00150.1 ↩

-

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Influenza (Flu): Past pandemics. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/basics/past-pandemics.html ↩

-

World Health Organization. (2021). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved 2021, April 16, from https://covid19.who.int ↩

-

Schnall, A. H., Roth, J. J., Ekpo, L. L., Guendel, I., Davis, M., & Ellis, E. M. (2019). Disaster-related surveillance among U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) shelters during the Hurricanes Irma and Maria response. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 13(1), 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2018.146 ↩

-

Brunkard, J., Namulanda, G., & Ratard, R. (2013). Hurricane Katrina deaths, Louisiana, 2005. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 2(4), 215-223, https://doi.org/10.1097/dmp.0b013e31818aaf55 ↩

-

National Institute on Aging. (2017). Supporting older patients with chronic conditions. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/supporting-older-patients-chronic-conditions ↩

-

Kirby, T. (2020). Evidence mounts on the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(6), 547–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30228-9 ↩

-

Tai, D. B. G., Shah, A., Doubeni, C. A., Sia, I. G., & Wieland, M. L. (2021). The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 72(4), 703–706. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa815 ↩

-

Hutchins, S. S., Fiscella, K., Levine, R. S., Ompad, D. C., & McDonald, M. (2009). Protection of racial/ethnic minority populations during an influenza pandemic. American Journal of Public Health, 99(2), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.161505 ↩

-

Collins, J., Polen, A., McSweeney, K., Colón-Burgos, D., & Jernigan, I. (2021). Hurricane risk perceptions and evacuation decision-making in the age of COVID-19. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 102(4), E836–E848. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-20-0229.1 ↩

-

Hill, S., Hutton, N. S., Whytlaw, J. L., Yusuf, J. E., Behr, J. G., Landaeta, E., & Diaz, R. (2021). Changing logistics of evacuation transportation in hazardous settings during COVID-19. Natural Hazards Review, 22(3). [https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000506](https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000506) ↩

-

Shultz, J. M., Kossin, J. P., Hertelendy, A., Burkle, F., Fugate, C., Sherman, R., Bakalar, J., Berg, K., Maggioni, A., Espinel, Z., Sands, D. E., LaRocque, R. C., Salas, R. N., & Galea, S. (2020). Mitigating the twin threats of climate-driven Atlantic hurricanes and COVID-19 transmission. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 14(4), 494–503. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.243 ↩

-

Secules, S., McCall, C., Mejia, J. A., Beebe, C., Masters, A. S., Sánchez‐Peña, M. L., & Svyantek, M. (2021). Positionality practices and dimensions of impact on equity research: A collaborative inquiry and call to the community. Journal of Engineering Education, 110(1), 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20377 ↩

-

Oulahen, G., Vogel, B., & Gouett-Hanna, C. (2020). Quick response disaster research: Opportunities and challenges for a new funding program. International Journal for Disaster Risk Science, 11, 568–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-020-00299-2 ↩

-

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Social determinants of health. Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health ↩

-

Freeman, C., Nunnari, N., Edgemon, L., & Marsh, K. (2021, April). Improving public messaging for evacuation and shelter-in-place: Findings and recommendations for emergency managers from peer-reviewed research. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_improving-public-messaging-for-evacuation-and-shelter-in-place_literature-review-report.pdf ↩

-

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, June 15). COVID-19: Cleaning your facility. Retrieved 2021, June 27, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/disinfecting-building-facility.html ↩

-

Arlikatti, S., Maghelal, P., Agnimitra, N., & Chatterjee, V. (2018). Should I stay or should I go? Mitigation strategies for flash flooding in India. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 27, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.09.019 ↩

-

Keim, M. (2008). Building human resilience: The role of public health preparedness and response as an adaptation to climate change. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 35(5), 508–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.022 ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Puerto Rico Quick Facts, 2010-2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/PR ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Census, U.S. Virgin Islands Demographics. https://www.uvi.edu/files/documents/Research_and_Public_Service/ECC/SRI/2010%20USVI%20Census%20Dempgraphic%20Prof%20Printable.pdf ↩

Collins, J., Polen, A., Dunn, E., Maas, L., Ackerson, E., Valmond, J., Morales, E., & Colón-Burgos, D. (2021). Compound Hazards, Evacuations, and Shelter Choices: Implications for Public Health Practices in the Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 6). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/compound-hazards-evacuations-and-shelter-choices