Risk and Health Communication During Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico and Hurricane Ian in Florida

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

This study evaluates risk and health communication by news media and government officials during Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico as well as Hurricane Ian in Florida. The study examines communication resources used to identify lessons learned and offers recommendations to improve information exchange during disasters. Using mixed research methods (quantitative and qualitative), investigators surveyed, interviewed, and held a roundtable discussion with key communicators who worked during Hurricanes Fiona and Ian to determine how they assessed, gathered, and disseminated information during and after these events. Preliminary results demonstrate that although many of those interviewed had reliable and correct information to share with their Spanish-speaking publics, they confronted multiple challenges in carrying out effective risk/health communication. News media challenges included limited health communication training for news staff and too few journalists assigned to cover weather-related hazards. Government challenges included personnel turnover and the need for integrated communication plans. These shortcomings have significant detrimental health consequences for key Spanish-speaking communities—who during times of great risk might not be well informed to prevent, mitigate, and recover from weather-related health emergencies. Policies and practices for health/risk communication need to be improved to better serve Spanish-speaking communities during emergency situations.

Introduction

Hurricanes are devastating natural hazards that occur frequently in Caribbean and Central Atlantic regions. Due to their geographical location, Puerto Rico and Florida are prone to these adverse weather events. In 2017, Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico’s communication infrastructure, critically reducing news media and government capabilities to inform the public about important health/risk related issues related to response and recovery (Modestti, 20181). That same year, Hurricane Irma also caused havoc in Southwest Florida. Both hurricanes were responsible for thousands of deaths. Six years later, given the devastation by Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico and Hurricane Ian in Central Florida, it is imperative to assess how news media and government information officials in both locations can effectively inform key publics—especially those at greatest risk—about health/risk matters. A central concern of this study is how to best prepare for, mitigate, and recover from disasters triggered by weather and other related hazards. This includes health predicaments due to lack of medical services or assistance, especially when water or food are lacking or contaminated, or when contagious diseases emerge and spread after a storm. This information can help us offer evidence-based recommendations to improve how media and government communicate to the public during future emergencies.

Risk communication is the sharing of information with the public or institutions about the probability and consequences of harmful events, to enable the public to make informed decisions to mitigate the effects of a threat (World Health Organization, n.d.2). Effective risk communication requires developing trust between organizations, people communicating risks, and the diverse audiences receiving information.

There is limited systematic research about health/risk communication policies and practices in Puerto Rico. Only very recently have scholars addressed these issues (e.g., Modestti, 2018; Nieves-Pizarro et al., 2019 3; Rosario-Albert & Takahashi, 20214; Takahashi et al., 20195; Takahashi, et al., 20226; Takahashi & Zhang, 20237). Similarly, limited research has addressed health/risk communication for the large and growing Spanish-speaking communities in Florida.

Data gathered in this study offers a broader understanding of challenges and needs of government and news personnel for reaching vulnerable populations that have high poverty rates, limited health facilities, and precarious housing conditions. Findings from this study will offer recommendations for improving education and training of news media and government health/risk communicators in Puerto Rico and Florida to help address diverse communities’ access to information during emergencies. This is a critical issue for the Latino populations in Florida who access alternative media in Spanish and/or English. Research findings will suggest communication policies/practices to enhance coordination between vital communication entities across multiple layers of local, regional, and state-wide staff. A forum will be held in Puerto Rico in July 2023 to present research findings and recommendations from this study. Another forum in Florida will be considered for a future date in collaboration with the Puerto Rico Research Hub of the University of Central Florida.

Literature Review

Disaster Vulnerability in Puerto Rico and Florida

Puerto Rico and Florida have been heavily damaged by multiple tempests in recent years. The destruction caused in 2017 by Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico has been classified as the greatest catastrophe in the history of the Island, with a death toll estimated at 4,645 (Fernandez, 20188; Kishore et al., 20189). Hurricane Maria revealed the fragility of Puerto Rico’s communication infrastructure (Modestti, 2018; Nieves-Pizarro et al., 2019; Rosario-Albert & Takahashi, 2021; Takahashi et al., 2019; Takahashi et al., 2022). Interruption of energy service, as well as the collapse of radio, television, and cell phone service isolated thousands of families (Modestti, 2018). Failures of communication infrastructure led to a public policy law (Act #5, 2018) declaring telecommunications as an essential service on equal standing with electrical power and potable water.

Challenges in Emergency Communication During Disasters

Communication is challenging during emergencies. Coverage of natural hazards is vital for public well-being (Graber & Dunaway, 201710) and government organizations must develop plans for response, recovery, and reconstruction efforts (Houston et. al., 201911). Those stranded or in need of shelter, assistance, or supplies rely on information from news media for survival and support (Perez-Lugo, 200412; Takahashi & Zhang, 2023). News media and government officials must respond with accurate, clear, and complete information rapidly and proactively to reduce potential risks (Dave, n.d.13).

Emergency news and information depend on clear and effective operational procedures carried out by news media and government officials. Expert communication skills are essential for government agencies, news media, and community organizations to reach vulnerable audiences from different sectors of society, particularly low-income populations with limited news and information sources. Devices such as radio sets and cell phones, replacement batteries and/or gas-based generators for electricity and electronic device chargers, are often scarce in remote rural areas, as witnessed in Puerto Rico during Hurricane Maria (Modestti, 2018). Walters and Hornig (199314) explained that during natural hazard events, news media often depend on victims and/or witnesses as information sources. Yet, journalists should have access to expert sources to learn how to most effectively present information gathered for providing the public with the best available advice (Hornig, Walters, & Templin 199115). To the best of our knowledge, no studies have systematically assessed how news information is gathered and disseminated during emergencies in Puerto Rico. Also, no studies evaluate government’s outreach efforts on the island. The same can be said regarding similar studies with Latino populations (be they Spanish- or English-speakers) in Florida.

Health Implications of Disaster Risk Communication

Emergencies may become crisis situations because of circumstances beyond the control of healthcare responders. The transition from emergency to crisis may occur because of insufficient or unsuccessful emergency health communication, such as failure to communicate the likelihood of exposure to health threats. This was experienced in New Orleans, in 2005, as noted by Cole and Fellows (200816), who described a “compounded communication failure” during the early phases of Hurricane Katrina, when officials and the media provided conflicting and/or confusing messages regarding the impact the storm might have on the levee system” (p. 218). They added that “for those residents familiar with the levee system’s vulnerabilities or those just seeking information to guide their decision-making, this confusion may well have been catastrophic” (p. 218). This suggests that, ultimately, health and lives of those affected were jeopardized.

It is imperative that emergency communication be culturally responsive and consider unique situations that may influence risk perception and preparedness by culturally diverse populations. A study by Wouter and colleagues (202117) illustrated how public concerns over the pandemic dominated risk perception and diverted the focus from hurricane evacuation plans during hurricane season. Increased focused attention to pandemic warnings and precautions may have diminished attention to health-related safety measures and risks, affecting preparedness and management of potential hazards caused by hurricanes.

Another important concern is the potential lack of effectiveness of risk communication with vulnerable underserved populations, especially immigrants and refugees (Kim & Kreps, 202218). People from such groups have limited English-language proficiency and limited information sources, which hinders their ability to understand crisis messages. Populations with limited access to the Internet may be left out in ways that could put their lives at stake. The term “digital divide” describes how decreased access to information technologies can harm racial and ethnic minorities, persons with disabilities, rural populations, and those with low socioeconomic status (Sanders & Scanlon, 202119). Although digital access is rising rapidly for almost all groups, a gap remains for vulnerable populations most likely to be underserved (Chang et. al., 200420). This is a major problem during health emergencies (Kreps, 202121, 202222).

The Role of Bioethics

Hurricane Maria’s impact on morbidity and mortality caught the attention of diverse disciplines and groups, including the bioethics community at national and international levels (Centro Latino de Bioética y Humanidades and Federación Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Instituciones de Bioética, 201823; Fábregas, 201924). The bioethical perspective argues that expert communication skills are essential at the interpersonal, organizational, and the social level because of bioethicists’ role in society: helping to safeguard public health and safety through the perspective of ethical analysis. The relevance of bioethics in disasters is illustrated by Klugman (201725) who argued that bioethics is essential for responding to and preparing for these hazard events. In 2009 and 2012, the Institute of Medicine recommended that governments undertake crisis and care planning, prioritizing communication to ensure that communities at risk during natural hazards adequately prepare to protect life, health, and property. Bioethicists have been involved in these efforts, especially in developing frameworks for ethics in decision-making, policy formulation, and operations during emergency planning (Fábregas, 2019, 202126; Subervi-Vélez & Fábregas-Troche, 202027).

Targeting Vulnerable Populations: A Public Health Approach

Piltch-Loeb and colleagues (202028) explored the need to educate local populations in Florida, Massachusetts, West Virginia, and Puerto Rico about emergency preparedness. They found that representatives from government agencies and local academic institutions with subject matter expertise could host community meetings in close collaboration with organizations and volunteer groups trusted by the community. They observed that the use of a directory of community assets, embedded in a mobile application, could enhance information sharing and facilitate the integration of community assets into preparedness efforts. This demonstrates that local leaders’ engagement in preparedness efforts is important to identify community assets that can be leveraged to address the needs of the most vulnerable segments of a community.

In 2021, the Puerto Rico Public Health Emergency Preparedness Academy was established in collaboration with Puerto Rico’s Health Department to bridge communication gaps and ensure an inclusive approach to preparedness for people with disabilities. Between March and September that year, the preparedness academy convened several sessions to instruct attendees on the basics of inclusive emergency management. Session participants formed the Access and Functional Needs Population Committee, a multidisciplinary team of health educators, evaluators, and doctors, among others, to meet regularly to push forward emergency planning. The preparedness academy plans to incorporate other public health topics beyond emergency preparedness, including health communications, cultural competency, health literacy, and LGBTQIA+ community needs. The team continues to discuss methods to reach more staff with these development opportunities.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico, research is warranted to assess whether these initiatives resulted in improved risk or health communication practices, including the use of social media (Eriksson, 201829). Research is needed to assess how lessons from previous research on vulnerable populations can be used by news media and government agencies in Puerto Rico as well as in Florida to meet the health/risk communication needs of Latino populations. Given their rising numbers, differential rates of adaptation, language challenges, and particular socio-economic conditions, Latino populations are an important target for addressing health disparities in disaster (Duany, 200230, 200831).

Research Questions

The present study focuses on examining the challenges that news personnel and government communication officials in the targeted regions faced during disasters, specifically the management of health/risk communication during Hurricanes Fiona and Ian. Although organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) have issued effective guidelines and training modules for disaster preparedness, recent events have shown that communities have been ill-prepared to face the devastating impact of hurricanes. The study addresses four questions:

- How did news media decision makers (news editors, assignment editors, journalists assigned to health and risk news) gather, evaluate, and disseminate crucial health and risk information prior to, following, and in the ongoing recovery efforts from Hurricanes Fiona in Puerto Rico and Ian in Florida?

- How did the government information officials (e.g., press officers, public relations staff, health/risk/emergency information staff) assess, gather, evaluate, and disseminate health and risk information prior to, following, and in the ongoing recovery efforts from Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico and Hurricane Ian in Florida?

- What similarities or differences distinguish the studied operations, practices, and policies of news media and government information personnel in Puerto Rico vis-à-vis Florida?

- What types of policy recommendations are needed to better meet the needs and challenges of the news media and government information personnel in Puerto Rico and Florida?

We also asked news media and government officials about the role social media played in their respective efforts, if they addressed the needs of particularly vulnerable populations, and if any of their communication efforts used guidelines set by expert agencies, such as the WHO or the CDC.

Research Design

To address the research questions, the study utilized a mixed method approach that included an online survey administered via Qualtrics, followed by personal interviews, and a roundtable discussion. Inquiries in both locations were centered almost exclusively on Spanish-speaking news media personnel and government officials.

Approval of the study was obtained from the University of Wisconsin, Madison Institutional Review Board (IRB) on December 12, 2022. The Qualtrics survey, which consisted of 13 multiple selection questions and two matrix table multiple choice questions (written in Spanish and in English), was then pre-tested in January 2023 with two senior communication practitioners in Puerto Rico who shared similar characteristics as study participants. The final versions of the survey were distributed to respondents in Puerto Rico and Florida in late January through early March 2023. The first page of the survey included the Consent Form, also made available in English or Spanish, so participants were able to agree to the research procedures beforehand.

Sample

Due to the specific inclusion characteristics and limited population of this study, the selection process warranted purposive sampling of subjects in Puerto Rico and Florida who had direct experience with risk communication during hurricanes Fiona and Ian. Even so, access to news media and government personnel was one of the researchers’ greatest challenges.

Personal contacts provided access to respondents from government and the news media, and with snowball sampling these subjects provided other possible respondents (Noy, 200832). The situation was more complicated in Central Florida because of lack of personal contacts. This required constructing a list of local news media organizations and government agencies to be contacted for the names and email addresses of potential respondents. One media contact in Miami suggested additional names. That effort led to more than two dozen potential study participants.

Data Collection Methods

Surveys

All potential survey subjects in Puerto Rico and Florida were sent emails with cover letters that included the Qualtrics survey link. This was followed by at least three repeated email requests and/or calls (when a phone number was available).

Interviews

Interviews were conducted with subjects who had not responded to the survey but were willing via phone or Zoom to share answers to the survey questions and their experiences and insights related to their news media or government work during Hurricane Fiona or Ian. Each conversation was scheduled in advance and all interviewees were duly oriented and affirmed consent at the beginning of each interview. Corresponding answers were recorded, also with consent of the interviewees, and relevant responses to the questions were incorporated accordingly to the Qualtrics data set.

Roundtable Discussion

To add sociohistorical context and expert opinions to the findings of the study, a roundtable discussion was conducted via Zoom with former government officials and local experts in health and risk communication in Puerto Rico. The session was scheduled in advance and all interviewees were duly oriented and affirmed consent at the beginning of the conversation. Key points from the respondents’ answers were analyzed using Dedoose.

Interview Guide

For the interviews, we asked questions from the online survey, which were answered in a conversational style, allowing respondents to expand and add concerns of their own related to health/risk communication during the hurricanes and other emergency situations. For the roundtable discussion, the following four questions were asked. These queries were considered by the research team members as the most central to the study. During their respective answers, which flowed in conversational style, additional topics and issues were mentioned by participants.

- Which types of information (programs, directives, protocols) have you found more useful to gather and disseminate news about risk and health during hurricanes and other disasters?

- What are, in your experience, the greatest challenges to communicating risk during emergency situations?

- How would you evaluate risk and health communication management by the government during disasters? (Please include examples of good and bad management).

- What suggestions can you offer to help improve news coverage on risk and health topics during disasters in Puerto Rico/Florida?

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

Though IRB approval of the study was obtained on December 12, 2022, the study did not involve vulnerable populations and did not carry any significant risks to the respondents, so no other ethical concerns were contemplated. The multidisciplinary composition of the research team enabled sharing intellectually diverse ideas across disciplines, making this a transdisciplinary research project as it analyzed, synthesized, and harmonized theory and methods from all their respective disciplines for a common and cohesive research goal: improving health and risk communication for the targeted populations.

Results

Altogether, data gathered from the online surveys, the interviews and the roundtable discussion yielded answers to the research questions and additional insights about health/risk communication practices and challenges in Puerto Rico and Central Florida. Although the total number of respondents was only 21, we were able to assess how news and information was gathered and disseminated related to Hurricanes Fiona in Puerto Rico and Ian in Central Florida.

In Puerto Rico, the survey included seven respondents from local news media, six males and one female, whose ages ranged from 40 to over 60 and work experience ranged from two to 31 years. In Florida, four participants from the media responded to the survey, two males and two females, whose ages ranged from 40 to 59 and work experience ranged from two years to 25 years. Among government respondents, five were from Puerto Rico; three males and two females in the 40 to 59 age range, and work experience ranged from 15 years to 32 years. In Florida, one male government person responded the survey; his work experience was more than 30 years, and his age was around 60 years old.

In Puerto Rico, key government officials answered the survey questions and shared additional insights during phone/Zoom interviews and conversations. They all had many years of experience in various health/risk and communication-related jobs.

Roundtable participants from Puerto Rico consisted of three women and one man. One participant was in the 20 to 29 range, one in the 40 to 49 range, and two in the 50 to 59 range. Regarding their occupations, one worked for the federal government, two for the local government, and one worked for a private institution. Regarding work experience, two of them had 5 to 10 years of experience, one had 16 to 20 years, and one indicated more than 10 years.

Survey Findings

Respondents from Puerto Rico and Florida reported similarities both in sources used to gather information on health and risk issues (National Weather Service, CDC, local government emergency management offices, FEMA, etc.), as well as sources of information for the dissemination of relevant emergency information (Associated Press, United Press, and American Broadcasting Companies, among others). Regarding the process to disseminate relevant emergency information about the hurricanes, most respondents disseminated relevant emergency information using their organization’s social media platforms as well as their own outlets.

The most widely used agency guidelines were the ones developed by CDC and WHO followed by state emergency management agencies. As for media respondents in Puerto Rico and Florida, none indicated using official risk communication guidelines. Most of the interviewees were not fully aware that these guidelines existed, and they responded that they used standard information dissemination guidelines provided by their media, which had no particular risk communication provisions.

As for risk communication training, government officials had received some training and were acquainted with widespread risk communication guidelines and policies. As for the news media personnel, only one had received some special training and was acquainted with some of the training modules or programs. For the most part, respondents did not follow or did not know about official risk communication guidelines but used their individual media’s procedures and policies (See Table 1 below).

Table 1. Respondent Level of Awareness of Available Risk Communication Trainings

| I don’t know about it | I know about it but have not taken it | I have taken it and it was useful | I have taken it but it was not useful | |

| CERT Training from FEMAa or AEMEADb | 1 | 2 | ||

| Training Specialized in Risk and Health Communication for Journalists | 2 | 2 | ||

| Risk and Health Communication Training Modules like those offered by WHOc/CDCd | 3 | 1 | ||

| Courses on Risk and Health Communication in Academic Institutions | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Risk and Health Communication Degrees/ Certifications in Academic Institutions | 3 | 3 |

Interview Findings

Puerto Rico

Respondents who answered the survey questions via phone or via Zoom provided additional insights. The use of technical language was one of the topics mentioned during those interviews. Several respondents indicated that it was sometimes hard for local people to understand the terms used by meteorologists or weather specialists. One government official from Puerto Rico said that there are challenges in terms of communicating messages at the local level: “Those in emergency management need the information from the [organization] to be more digested. (They do not understand terms such as coordinates.” This quote shows more educational efforts should be made on how best to provide non-technical messages to local government (municipalities) and to local people in Puerto Rico.

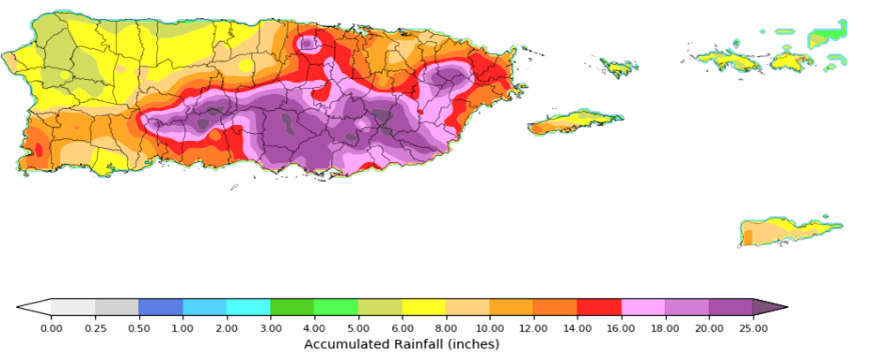

Another technical language challenge mentioned by one of our respondents is that the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale currently used in news and information warnings has proved to be insufficient to adequately convey potential risk to the public because it points to risk in terms of hurricane winds but does not consider the flood potential. This was cited as one of the main reasons that Hurricane Fiona had such a devastating effect as people prepared for a Category 1 hurricane, which is the lowest in the hurricane scale, but were not expecting the intense and consistent rain and flash floods caused extreme damage to crop, infrastructure and communities. Figure 1, on the next page, shows Hurricane Fiona rainfall totals in Puerto Rico.

Figure 1. Rainfall for Puerto Rico During Hurricane Fiona

An additional topic was the credibility of official sources. In Puerto Rico, citizens strongly trust official sources because of their reputation and credibility. Overall, respondents indicated a strong relationship between the government agencies and the media. As one government official from Puerto Rico said,

The [name of government organization] is respected as an official source… In Puerto Rico it is known that weather forecasters are on the side of the [name of government organization]. Annually they hold workshops with all the local weather forecasters. We have a strong and open relationship with those meteorologists. In terms of communication, they stay on the same page, they give the same information all the time.

A change of culture was yet another topic mentioned in Puerto Rico. In terms of risk management, several respondents highlighted a need to work more on planning and being more proactive. For instance, one government official said, “In Puerto Rico we are in a culture of putting out fires. We are not proactive.” The change of culture warrants a risk communication specialist as part of the staff as stated by an official in the top hierarchy of the Department of Health of Puerto Rico, “The contribution of this type of professional is key and helps me to look for the best strategies and support material to the point that a Manual on Risk Communication is in the process of publication.”

Florida

Interviewees from Florida expressed concerns with the notion that the underserved populations face more challenges in getting information. Hispanics—especially non-English speakers—don’t have as many options as the English-speaking population in terms of risk information during emergencies. One of our interviewees, a mass media specialist from Florida, shed light on the problems underserved populations face regarding access to critical information during disasters, saying:

The Anglo population is more aware of weather situations because they have more news and outlet options. That is not the case for the Hispanic population at large. They do not have the same information due to language barriers, or because of fear of communicating with government agencies because of their undocumented status.

Another theme mentioned during the interviews in Florida was the frequent and widespread use of social media by Latinos, and the value of leveraging these outlets to inform Latinos about natural hazard risks. As one mass media specialist said, “We also keep in mind that most people, especially Spanish speakers, use social media and look at live streams to know what is going on with weather conditions. Latinos communicate via social media like no other.”

Satellite image of Hurricane Ian making landfall in Florida on September 28, 2022. Image Credit: NASA Earth Observatory.

Roundtable Findings

Roundtable participants in Puerto Rico were very knowledgeable about risk communications procedures and most of them worked in government agencies during Hurricane Maria, so they had a very clear picture of what changed since then. Their discussions also repeated concerns mentioned by interviewees and provided context to the collected data.

These subjects agreed that the situation was much worse during Hurricane Maria than during Hurricane Fiona because in 2017 the power grid and communication infrastructure were devastated. Nevertheless, all expressed concerns that the situation could recur because not all the infrastructure has been replaced or even repaired. They also agreed that the public’s lack of education about emergency situations is a big challenge. They further expressed concerns about poor communication between officials of the central government and those of small municipalities—differences sometimes based on political affiliations.

Common topics were language challenges, lack of culturally responsive communication, and “a lack of credibility of the institutions they represent.” More to the point, a respondent addressed the lack of cultural context of official communication efforts, and the lack of solidarity and empathy with hurricane victims, adding that, “Risk communication is being issued from ‘privilege’,” meaning that most government officials are not familiar with the realities of the communities that they address, rendering the information useless or irrelevant to the populations they want to reach.

However, respondents generally agreed that current risk communication efforts by the Puerto Rico Emergency Management Agency are good and that the staff is very knowledgeable about risk communication management and has credibility among the public. A pointed critique was that often during press conferences, politicians take over and, at times, there are too many government officials delivering the information causing confusion with the most crucial messaging. A case in point was regarding the lack of credibility stemming from past experiences with hurricanes that were announced as major threats but then diverted their course and did not affect the Island.

Even so, all agreed that official information from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Weather Service, and National Hurricane Center was most useful and trusted, and that there is a healthy working relationship between government officials and representatives from these agencies. As for risk and heath communications during emergencies among the local government, they affirmed that there are many challenges and that there is much room for improvement, not because of lack of training and information, but because the emergency communication infrastructure is too big, and there is lack of an integrated communications management system. Regarding that concern, one participant mentioned the lack of feedback between agencies and recalled that valuable tabletop preparedness exercises are not being conducted anymore.

Roundtable participants evaluated media coverage as precise and correct, but in some cases the news was sensationalistic, guided more by ratings than actual risk communication. One respondent attributed this to the fact that media work based on a business model, not necessarily on a community service model. There was also mention of the public’s ample use of social media and the problems and challenges it caused especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As for recommendations, participants suggested education programs for journalists who cover weather-related developments and for government communication officials who deal with the media and the public. Moreover, respondents pointed out the importance of developing a more integrated and simplified communication management system, as well as the value of integrating community leaders and private corporations during crises communication management.

Overall

During hurricanes Fiona and Ian, media personnel and government officials from both locations indicated having had access to reliable, accurate and complete information from trusted official sources. These included the State Agency for Emergency Management and Disaster Assistance, (Agencia Estatal para el Manejo de Emergencias y Administración de Desastres—AEMEAD), FEMA, the National Weather Service, the CDC, the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus, and Puerto Rico’s Department of Health and Emergency Operations Center. For updated information about the threats, participants also mentioned the following news services: Agencia EFE (from Spain), American Broadcasting Company (ABC news), Associated Press (AP), Cable News Network (CNN), Reuters, and United Press International (UPI).

However, participants, especially from the news media, suggested there was an overall lack of formal training regarding risk communications about the events. For example, in-house training concerning health and risk news coverage is rare or is very limited in small media companies. Reporters assigned to hazards stemming from weather or other causes are not properly trained about such matters. In small media companies there are no journalists specifically assigned to cover hazards or other risk issues, which leaves the task to whichever reporter might be available at the day/time of an event. During the interviews, media respondents nevertheless indicated they were interest in learning more about and being trained in health and risk communication.

Respondents reported that government information officials frequently change when a new political party wins an election. This was a problem noted especially by respondents in Puerto Rico who explained that the newly appointed officials are often not formally trained in health/risk communication and sometimes modify communication and other emergency-related policies and procedures. This lack of continuity makes it difficult to provide consistent communication that builds upon previous experience with adverse weather events, hampering both effective response management and health and risk communication to the public.

Another finding concerns the interactions between news staff and government representatives. More than once, respondents mentioned that those interactions are contingent on pre-established working relationships between persons from these entities. When working relationships are well-established, information exchanges between them flows effectively; otherwise, the exchanges might be rocky or non-existent.

A final overall finding concerns the rise and frequent use of social media, which have become a primary channel to communicate risk/health news and information by news media as well as government officials through outlets of their respective entities (although some journalists have been known to post/share using their individual accounts). However valuable these social media are, some respondents mentioned that government officials and even news reporters are facing challenges that emerge when people seek their own unofficial sources (friends, family, others) via their particular social networks and upon doing so question or disregard the official and more reliable information sources. They expressed problems with mis/disinformation constantly being widely disseminated over social media. A repeated example related to mis/disinformation was about the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccines.

Discussion

Hurricane Fiona was the third most costly hurricane to hit Puerto Rico (Pasch, Reinhert & Alaka, 202333), while Hurricane Ian may have been Florida’s costliest (Freedman, 202234). In Puerto Rico, the National Hurricane Center attributed the high costs to multiple factors, such as falling residential roofs, collapse of bridges, and widespread agricultural and power loss even in areas not directly hit by the hurricane. The damage in Florida was mostly from the coastal surge that wiped out homes and business near the shore, and provoked record-high inland flooding. Both disasters raise questions and concerns regarding the efficiency and usefulness of health/risk communication. Regardless of the location and crisis event, communication competency has vital implications for news media and government officials, which must develop trust between each other as well as between the public and personnel from those entities. When health/risk news and information operations are not properly coordinated, the public is likely to be adversely affected during emergency situations.

Results of our study indicate that although many of the interviewed subjects had reliable and correct information to transmit to their respective Spanish-speaking publics, they confronted multiple challenges carrying out effective health/risk communication. In Puerto Rico, as well as in Florida, news media challenges included limited health/risk communication training of news staff and few journalists assigned to cover potential natural hazards. Government challenges included personnel turnover and the need for integrated communication plans.

Based on our findings, we propose that media coverage strategies and government information policies be redeveloped to address the challenges emerging from major changes in news staff or government personnel involved in risk communication. This implies the need to establish and implement consistent risk communication policies, especially when new personnel are appointed. Also, efforts need to be made to preserve lessons learned from prior hazard events for guiding future media coverage and government communication strategies. Health/risk communication literacy among professionals in media and government in Puerto Rico and Florida also needs to be addressed. Another important recommendation is that an alternative natural hazard risk evaluation system be used or created. The current Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale has not proved to be an adequate risk predictor as it does not accurately report, for example, the flood potential of a hurricane, as was appreciated during Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico and Ian in Florida. In essence, it seems evident to the research team that policies and practices of news operations and government information officers need improvements to diminish health/risk communication challenges during hazard conditions.

A positive outcome from this study was the productive, mutually cooperative relationships established with the respondents. For example, after interviews with news media respondents were finished, investigators provided them with webpage links for CDC, WHO and local risk communication training programs. Researchers also established collaborative relationships with government officials and agreed to share the study’s findings and recommendations to help strengthen risk communication with vulnerable/difficult-to-reach populations during emergencies. Possible future research was also discussed and received with interest by the interviewees.

Conclusions

Public Health Implications

Hazards of diverse types, including those caused by severe weather, directly impact public health. They may increase morbidity and mortality associated with chronic and infectious diseases, thus impacting the healthcare system (Giorgadze et al., 201135). This was especially true regarding Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico and can also be appreciated in emerging data from Fiona, as well as Ian, in Central Florida. Existing health disparities when comparing Puerto Rico to the continental United States, combined with governance issues and financial constraints placed on the territory, lead to an increased vulnerability among those living in the archipelago, many of which leave the Island to then face new but similar challenges in Florida and elsewhere.

For news media personnel, there is an evident need to promote and implement regular and continuous training regarding health/risk communication. By introducing news media training programs, coverage continuity can be improved. Also, improved policies and guidelines are needed for conducting coordinated health/risk communication during adverse hazard events. Given that the public is the most important actor in any public health emergency, timely, useful, and strategic health/risk communication is imperative. In essence, much more efficient communication policies and practices must be central features in responding to the full range of emergency situations (Bennett, 202136).

Puerto Rico and Florida have different agencies, systems, and chains of command, but the present study demonstrates that the challenges of health/risk communication are similar. Past hurricanes have offered valuable lessons in risk communication management that have evolved in both locations. But more needs to be done. Climate change suggests that adverse weather events will continue to increase in intensity and disaster potential. Steps must be taken to ensure preparedness, not only by the media and government, but also within the communities at risk. This can only be achieved through public education and integrated, evidence-based risk communication management before, during and after emergency events.

Limitations

This research project has various limitations that merit mention. Researchers faced problems recruiting respondents from news media and government officials, especially in Florida where repeated calls and email messages did not result in responses from government personnel to the online survey and very limited responses via phone calls/Zoom.

One reason for this difficulty might have been the high turnover of reporters responsible for covering risk/health news about the hurricanes. This made it extremely difficult to reach the precise ideal respondents, since some media directors, for example, weren’t there at the time of those events. Turnover also occurred with government information officials during the hurricanes; this also limited access to the corresponding information officers.

Ideally, it would have been best to collect data on site immediately or very shortly after the hurricanes to gain direct access to news media and government staff most directly engaged in reporting, gatekeeping news stories/information, and/or communicating with the public. Delays in getting funding, putting working plans into action, and getting IRB approval created a time lag for data collection. Nevertheless, the research team persisted and overcame these limitations and was able to collect very relevant and revealing data as reported herein.

Future Research Directions

Future studies on these issues should include systematic and keenly focused content analyses of the actual news about health and risk in both commercial as well as alternative news media. Content analyses of social media postings on health and risk would also add significant insights into the characteristics and patterns of what was disseminated and what was circulated prior to, during, and after the storms. A more comprehensive study would also benefit from survey research to assess which news media, government information sources, and of course social media are used and relied upon by Puerto Ricans on the Island and by Spanish-speaking populations on the U.S. mainland who are affected by an actual risk/health crisis. Finally, a broader interpretation of the findings of this study would benefit from the application of health communication theories related to vulnerable populations as well as public health ethical frameworks that guide efficient decision-making.

Acknowledgments. We would like to express our gratitude for the following institutions and individuals who provided assistance and support during this project: The Center for Health and Risk Communication George Mason University, Fairfax, VA; Ms. Priscilla Vázquez, retired public relations director of the Asociación de Industriales de Puerto Rico; Dr. Rafael Gracia, professor and former director of the University of Puerto Rico’s radio station; Ms. Brenda Reyes, communications director at Puerto Rico’s EPA; Mr. Roberto Vigoreaux in Orlando; and Ms. Marian Cobián, AEMEAD's communication director.

References

-

Modestti, M. (2018). Desafíos de la comunicación en un país incomunicado: Puerto Rico y el huracán María. Intersecciones, 2. https://copu.uprrp.edu/desafios-de-la-comunicacion-en-un-pais-incomunicado-la-comunicacion-enpuerto-rico-ante-el-paso-del-huracan-maria/ ↩

-

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Risk communication and community engagement. Retrieved July 1, 2023, from https://www.who.int/emergencies/risk-communications ↩

-

Nieves-Pizarro, Y., Takahashi, B., & Chavez, M. (2019). When everything else fails: Radio journalism during Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Journalism Practice, 13(7), 799–816. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1567272 ↩

-

Rosario-Albert, L. & Takahashi, B. (2021). Emergency communications policies in Puerto Rico: Interaction between regulatory institutions and telecommunications companies during Hurricane Maria. Telecommunications Policy, 45(3), 102094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2020.102094 ↩

-

Takahashi, B., Zhang, Q. & Chavez, M. (2019): Preparing for the worst: Lessons for news media after Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, Journalism Practice, 14(9), 1106-1124. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1682941 ↩

-

Takahashi, B., Zhang, Q., Chavez, M. & Nieves-Pizarro, Y. (2022) Touch in disaster reporting: Television coverage before Hurricane María. Journalism Studies, 23(7), 818-839. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2022.2038237 ↩

-

Takahashi, B. & Zhang, Q. (2023). Place in disaster coverage: Newspaper coverage of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, Journalism Practice, 1-19. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17512786.2023.2190150 ↩

-

Fernandez, I. (2018, May 30). El huracán María causó en Puerto Rico 4.645 muertos, no los 64 “oficiales. EFE:Verde. https://efeverde.com/puerto-rico-huracan-maria-4-645-muertos-no-64-oficiales/ ↩

-

Kishore, N., Marqués, D., Mahmud, A., Kiang, M. V., Rodriguez, I., Fuller, A., ... & Buckee, C. O. (2018). Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane María. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(2), 162-170. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmsa1803972 ↩

-

Graber, D. A., & Dunaway, J. (2017). Mass media and American politics (10th ed.). CQ Press. ↩

-

Houston, T. K., Richardson, L. M., & Cotten, S. R. (2019). Patient-directed digital health technologies: Is implementation outpacing evidence?. Medical Care, 57(2), 95-97. ↩

-

Perez‐Lugo, M. (2004). Media uses in disaster situations: A new focus on the impact phase. Sociological inquiry, 74(2), 210-225. ↩

-

Dave, R. K. (n.d.). Role of media in disaster management. https://www.osou.ac.in/eresources/role-of-media-in-disaster-management.pdf ↩

-

Walters, L. M. & Hornig, S. (1993). Profile: Faces in the news: Network Television news coverage of Hurricane Hugo and the Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 37(2), 219-232. ↩

-

Hornig, S., Walters, L., & Templin, J. (1991). Voices in the news: Newspaper coverage of Hurricane Hugo and the Loma Prieta earthquake. Newspaper Research Journal, 12(3), 32-45. ↩

-

Cole, T. W. & Fellows, K. L. (2008). Risk communication failure: A case study of New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina, Southern Communication Journal, 73(3), 211-228. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10417940802219702 ↩

-

Wouter Botzen, W. J., Mol, J. M., Robinson, P. J., Zhang, J., & Czajkowski, J. (2022). Individual hurricane evacuation intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights for risk communication and emergency management policies. Natural Hazards, 111, 507–522, [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069- 021-05](https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069- 021-05) ↩

-

Kim, D. K. D. & Kreps, G. L. (2022). Global health communication for immigrants and refugees: Cases, theories, and strategies. Routledge. ↩

-

Sanders, C. K., & Scanlon, E. (2021). The digital divide is a human rights issue: Advancing social inclusion through social work advocacy. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 6(2), 130–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-020-00147-9 ↩

-

Chang, B. L, Bakken, S., Brown, S. S., Houston, T. K., Kreps, G. L., Kukafka, R., Safran, C., Stavri, P. Z. (2004). Bridging the digital divide: Reaching vulnerable populations, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 11(6), 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M1535 ↩

-

Kreps, G. L. (2021). The role of strategic communication to respond effectively to pandemics. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 16(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2021.1885417 ↩

-

Kreps, G. L. (2022). Addressing challenges to effectively disseminate relevant health information. World Medical & Health Policy, 14(2), 220–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.528 ↩

-

Centro Latino de Bioética y Humanidades & Federación Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Instituciones de Bioética. (2018, February 1). Primera Jornada Internacional de Bioética y Desastres Naturales. Fideicomiso de Ciencias y Tecnología [Conference]. San Juan, Puerto Rico. ↩

-

Fábregas, S. (2019). Declaración de San Juan en la XII edición de FELAIBE en Puerto Rico, San Juan. Acta Bioética, 25(1). https://actabioethica.uchile.cl/index.php/AB/article/view/53579/57135 ↩

-

Klugman, C. (2017). Harvey and Irma: Bioethics in natural disasters. Bioethics Today. https://bioethicstoday.org/blog/harvey-and-irma-bioethics-in-natural-disasters/ ↩

-

Fábregas, S. (2021). Reflexiones Bioéticas: Hacia un paradigma en la planificación de la toma de decisiones en la atención de salud. 13ra Ed. Archivos Médicos Dominicanos (AMED). República Dominicana, 5 de mayo. ↩

-

Subervi-Vélez, F. & Fábregas Troche, S. (2020). Comunicación bioética preventiva: Opciones estratégicas ante situaciones de emergencia. In S. Fábregas Troche & F. León Correa (Eds.), La comunicación: Herramienta vital para la bioética en voces de las tres Américas (pp. 148-159). CELABIH, FELAIBE. ↩

-

Piltch-Loeb, R., Savoia, E., Goldberg, B., Hughes, B., Verhey, T., Kayyem, J., ... & Testa, M. (2021). Examining the effect of information channel on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Plos one, 16(5), e0251095. ↩

-

Eriksson, M. (2018). Lessons for crisis communication on social media: A systematic review of what research tells the practice. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(5). https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1510405 ↩

-

Duany, J. (2002). The Puerto Rican Nation on the Move: Identities on the Island and in the United States. University of North Carolina Press. ↩

-

Duany, J. (2008, November 7-8). The Puerto Rican Diaspora to the United States: A Postcolonial Migration? [Workshop paper]. Postcolonial Immigration and Identity Formation in Europe Since 1945: Towards a Comparative Perspective, Amsterdam, Holland. ↩

-

Noy, C. (2008). Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(4), 327-344. ↩

-

Pasch, R. J., Reinhart, B. J. & Alaka, L. (2023). Hurricane Fiona. National Hurricane Center tropical cyclone report. National Hurricane Center. https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL072022_Fiona.pdf ↩

-

Freedman, A. (2022, October 7). Hurricane Ian may have caused $67 billion in damages, a top 5 U.S. storm. Axios. https://www.axios.com/2022/10/07/hurricane-ian-damage-estimate-costliest-storm-florida ↩

-

Giorgadze, T., Maisuradze, I., Japaridze, A., Utiashvili, Z., & Abesadze, G. (2011). Disasters and their consequences for public health. Georgian Medical News, 194, 59-63. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21685525/ ↩

-

Bennett, R. (2021). Health literacy and disaster risk communication. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/health-literacy-disaster-risk-communication-russ-bennett ↩

Subervi-Vélez, F., Fábregas-Troche, S. M., Modestti-González, M., Kreps, G. L., & García-Cosavalente, H. P. (2023). Risk and Health Communication During Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico and Hurricane Ian in Florida (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 29). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/risk-and-health-communication-during-hurricane-fiona-in-puerto-rico-and-hurricane-ian-in-florida