Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood is outfitted with new microgrid technology. Image courtesy of ComEd.

Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood is outfitted with new microgrid technology. Image courtesy of ComEd.

By Jeffrey Schlegelmilch, Jackie Ratner, Shay Bahramirad, and Aleksi Paaso

So much of our modern, technological world depends on reliable access to electricity, it can be difficult to imagine what life without it would be like for a few hours, let alone days. But that’s exactly what the people who prepare our infrastructure to withstand disaster must do.

Power outages can have far-reaching and cascading impacts. When the power goes out, communications systems fail, hospitals and healthcare facilities can’t function at full capacity, and those on life-supporting medical equipment can be left in a lurch. Vulnerable community members, such as the elderly and the very young, are threatened by extreme temperatures when there is insufficient power to operate heating and cooling systems. As climate change contributes to increasing extremes, functioning heating and cooling systems could come to be a matter of life or death.

The importance of electric utilities in our day-to-day lives has led the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to designate them a community lifeline. FEMA considers these lifelines to be so integral that they “enable all other aspects of society to function” and recommends that they are prioritized for reestablishment after a disaster and continuously improved and stabilized in non-disaster times.

This is especially important for traditional electrical infrastructure, which has aged beyond its intended lifespan and was not built to withstand today’s climate. Experts have projected tens of thousands of potential deaths in the United States in the next few decades attributable to extreme heat. Add to this the burden that extreme cooling places on the grid, and we can anticipate serious public health consequences if electric distribution technology cannot keep pace.

Fortunately, there are emerging strategies and technologies that can sustain electric lifelines, especially in emergencies. Experts from government, academia, and industry see potential in the use of microgrids, which are small power grids that can either be connected to the main grid or—during an emergency—be disconnected from it to keep locally generated power flowing. When resources such as solar panels and energy storage are also connected, a microgrid controller can route and optimize power within the grid’s footprint. If the larger electrical grid goes down, the distributed energy sources within the microgrid will keep the lights on. Those in the grid’s footprint are unlikely to experience extended power disruption and can serve as a resource to those outside the microgrid and help keep regional infrastructure, such as healthcare centers, shelters and responder operations, functioning.

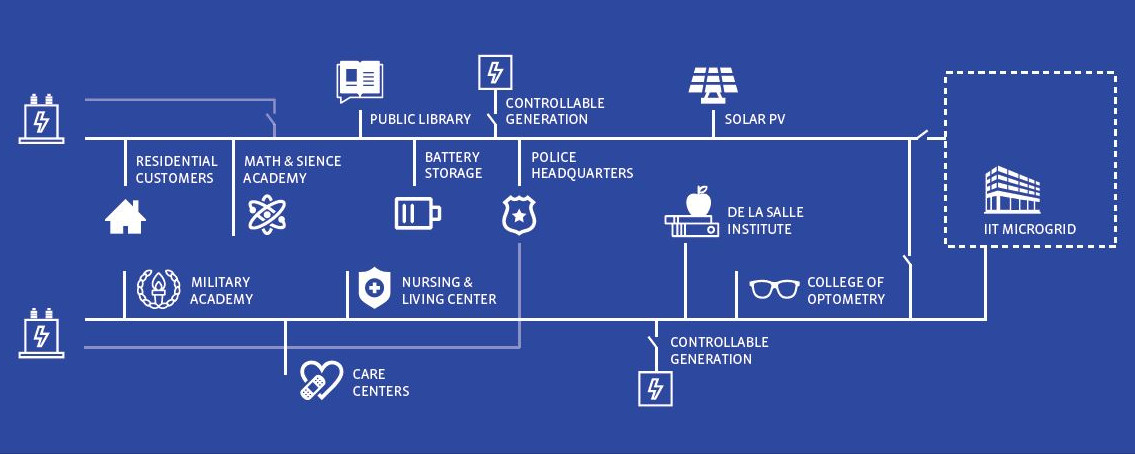

Such a microgrid now exists in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. The microgrid cluster, built by Chicago-based ComEd with the help of U.S. Department of Energy grants, is the first utility-operated microgrid cluster in the United States. The cluster includes a microgrid at the Illinois Institute of Technology and serves approximately 1,000 residences, businesses, and public institutions.

The Bronzeville microgrid cluster at the Illinois Institute of Technology. Graphic courtesy of ComEd.

The Bronzeville microgrid cluster at the Illinois Institute of Technology. Graphic courtesy of ComEd.

Since Chicago experiences extreme lows and heavy snowfall in the winter, high temperatures and humidity in the summer, and intense winds year-round, it’s an excellent location to gauge the resilience of such a project. During a disruptive event, power in the community of Bronzeville could continue to operate, thanks to community solar and energy storage that would allow the microgrid function in isolation.

To further increase the resilience of the project—and advance overall preparedness research and science—ComEd and the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia (NCDP) University’s Earth Institute have created a partnership that incorporates insights in social vulnerability with advances in electrical grid design and implementation. This will include a disaster simulation that will be held within the Bronzeville microgrid to examine and better understand the benefits of an interconnected approach. The work will eventually help inform further improvement to microgrid design and deployment strategies.

From the rolling blackouts required to reduce wildfire risk in California to Puerto Rico’s aged and crumbling infrastructure that contributed to the Hurricane Maria death toll, we know that power system failures can exacerbate disasters. But new technologies, combined with the latest in disaster preparedness and science, can change these narratives from stories of failure to lessons in resilience.

Jeffrey Schlegelmilch is the deputy director for the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University’s Earth Institute. In this role, he oversees the operations and strategic planning for the center. Schlegelmilch also oversees projects related to the practice and policy of disaster preparedness. His areas of expertise includes disaster policy, public health preparedness, community resilience, and the integration of private and public sector capabilities.