By Jolie Breeden

Public domain: Freedom House Syrian Refugees

Public domain: Freedom House Syrian Refugees

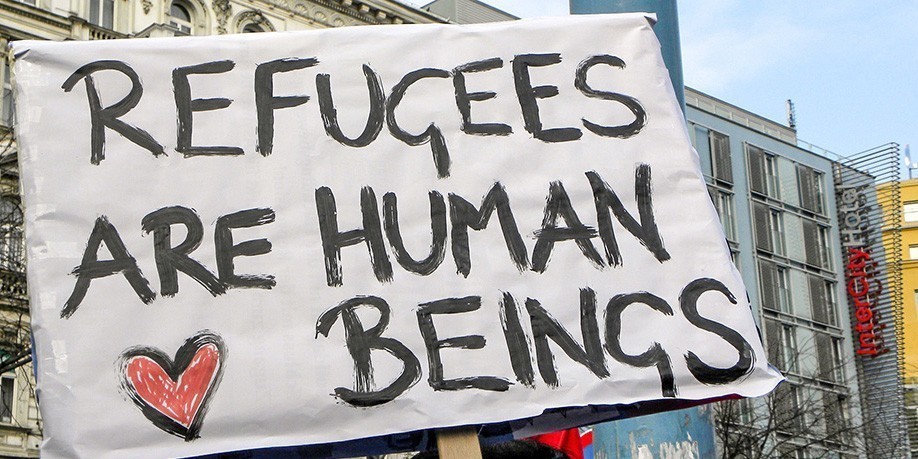

Last year, throngs of migrants coursed through Europe seeking escape from war-torn countries in the Middle East. Or some might say scores of refugees. Or hordes of asylum seekers. Whatever the “masses” are called, what they’re not often referred to as is people—more than a million individual men, women, and children who are struggling to find safety and escape unlivable conditions in places that were once their homes.

The issue of generalization in this case is significant—while reporters and politicians have a need to communicate the overarching impacts of mass migration, it’s difficult to apply appropriate terminology to a group of people who are very different. They hail from different countries for different reasons, and often times those reasons do not fit neatly into legal or semantic categories.

What follows, then, is a series of broad brush terms that are at best inaccurate, but at worst derogatory and demeaning. Labeling people with words such as migrant, refugee, and asylum seeker, while simultaneously referencing them with dehumanizing language (for instance, flood wording is popular—migrants are said to “stream” over borders, they come in “waves,” or “pour in” from other countries), is not just a matter of poor word choice. At a fundamental level, it strips individuals of their humanity.

Not that there hasn’t been any thought given to what these individuals should be called—in fact, quite the opposite. World leaders often find it politically expedient to use one term rather than another. News agencies have debated which terminology is best used in accurate reporting. Humanitarian agencies have urged the public to be cognizant of how labeling newcomers can impact community integration.

But in the end, regardless of the vocabulary used and how well meaning (or self-serving) it is, what is most important is to realize that the words that are being applied to these crisis victims—and the way they’ve been generalized—have huge political, social, and individual impacts.

What’s in a Name?

The terms most commonly applied to those embroiled in the current crisis are migrant (or economic migrant), asylum seeker, and refugee. For much of the public following the conversation, these words are interchangeable. But since they have very distinct—and in some cases, legal—meanings, it’s useful to start with a clear understanding of their import.

Migrant. By dictionary definition, any one who migrates from one location to another, especially for employment purposes, is a migrant. But it would be disingenuous to pretend that the populace uses the term this way. For instance, no one is likely to call a person moving to a nearby city for a new job a migrant. And that speaks to the current connotation of the word, which is indicative of a person who comes from another country to seek a better lifestyle or more lucrative employment. Often times, there is a certain amount of judgment associated with the term—migrants are seen as usurpers or nuisances who threaten to take resources from existing residents.

In connection with the current crisis, a level of politics has also been added. Nations do not have the same legal responsibilities for migrants—sometimes called economic migrants to underscore that they don’t seek safety, but monetary gain—as they do for asylum seekers or refugees. Where the treatment of refugees is defined by the 1951 Refugee Convention Protocol and associated documents (UNHCR 2011), migrants come under individual countries’ immigration rules. It’s convenient then to term individuals fleeing across the Mediterranean as migrants when giving them citizenship is unpopular or feared, because nations have more leeway in deciding if they can stay or go.

Asylum Seeker. According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), an asylum seeker is an individual who claims to be a refugee, but has not formally been given refugee status. In the strictest sense, this would mean a person who as applied for refugee status under the auspices of the 1951 protocol and is waiting for their application to be approved (a process that is handled through national asylum systems).

Like the term migrant, however, asylum seeker isn’t an absolute, especially when applied generally. Rarely is it possible to know that each individual in a group has formally applied for asylum. To further confuse the issue, the cases where it’s most likely to apply—for instance, when referring to a group coming from what the UN would call a “refugee-producing” area, such as Syria or Afghanistan—there is a mechanism in place that would more accurately define those people as prima facie refugees .

Refugee. Of all the terms being bandied about, refugee is the one least open to interpretation. Refugee indicates a legal status granted to people fleeing from war or persecution across international boundaries. There is the understanding that returning such people to their homeland could result in death or loss of freedom. As mentioned before, the determination of refugee status is largely guided by the 1951 protocol.

Unfortunately, while refugee might be the clearest term available, it’s not much better than migrant or asylum seeker for communicating general ideas about current migration. For instance, many people have argued that the media should refer to the current crisis as a refugee, rather than a migrant, crisis. Although the aim is to more accurately characterize the direness of the situation for those entering Europe, most of them are not yet refugees or even asylum seekers in a true sense. Even if a prima facie designation had been made, recent migration is made up of both migrants and soon-to-be refugees and asylum seekers traveling side by side.

Does a Rose Truly Smell as Sweet?

It might seem niggling to make such distinctions, but the wording used is important. In real ways, choosing to label those now migrating can impact both how the public perceives them and how they see themselves.

UNHCR Spokesman Adrian Edwards recently made this point in an article about why the agency chooses to use the phrase “refugees and migrants,” over other options (Edwards, 2015).

“Blurring the two terms takes attention away from the specific legal protections refugees require,” Edwards wrote. “It can undermine public support for refugees and the institution of asylum at a time when more refugees need such protection than ever before…. So, at UNHCR we say ‘refugees and migrants’ when referring to movements of people by sea or in other circumstances where we think both groups may be present – boat movements in Southeast Asia are another example…. We hope that others will give thought to doing the same. Choices about words do matter.”

Others have indeed given thought to the matter. Al Jazeera, notably, made a strong statement about their decision to stop referring to the current situation as a migrant crisis and begin calling it a refugee crisis.

“The umbrella term migrant is no longer fit for purpose when it comes to describing the horror unfolding in the Mediterranean”

Although the latter might not be as accurate, it’s clear that the news agency is cognizant of how their portrayal normalizes the crisis in the minds of the public, and they want the impression to adequately express the seriousness of the situation. In a blog post that explains the thinking that went into their decision, Al Jazeera Online Editor Barry Malone paints a picture of the risks taken by Mediterranean immigrants and calls out world leaders and anyone else who would downplay the dangers by using the term migrant (2015).

“The umbrella term migrant is no longer fit for purpose when it comes to describing the horror unfolding in the Mediterranean,” he wrote. “It has evolved from its dictionary definitions into a tool that dehumanizes and distances, a blunt pejorative.”

It’s not unusual for a previously innocuous word to take on disparaging or deprecatory meanings. And in such cases, there is often a definitional lag where the negative usage is propagated because it hasn’t yet been incorporated in the definition, writes Charlotte Taylor, a linguist at the University of Sussex (2015).

“This kind of semantic degrading is common for words relating to controversial topics. We need only think of the endless cycle of terms used to describe people with disabilities, which often develop into insults and are eventually replaced,” she wrote. “In the early stages of a meaning change there is a tendency for people to resist the new interpretation, by claiming that they are using the dictionary definition. But dictionaries do not merely define words – they also describe how they are used. If a negative meaning develops this will be listed.”

So while some proponents strive for more accuracy in naming, there is perhaps some benefit in using terminology that is less precise, but also less inflammatory. In doing so, its possible that news organizations and others communicating about human migration can limit the negative impact these terms have on new arrivals.

Sticks and Stones—and Yes, Words—Can Really Hurt You

As Taylor points out, “naming is a choice which reflects not just a process, but a view of that process and the people involved.” As such, the words used to describe those migrating to Europe are telling both in terms of how the community receives them, and in how they perceive themselves.

On an individual level, Paula Madrid, a New York-based psychologist who works with asylum seekers and displaced people, has seen firsthand how people unconsciously take on the labels that society places on them.

“You’ll meet them and they’ll say, ‘I’m an immigrant,’ or ‘My parents were immigrants,” she said. “I’ll say ‘Wait, tell me about yourself. What do you like to do?’ That sort of thing. Anytime you label someone, you’re really impacting the way they think about the world, but also the way they think about themselves.”

Madrid, a former director of the psychosocial preparedness division of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University, has a long history of working with people made vulnerable by conflict and crisis. Her clients sometimes report being seen as a threat or not being readily accepting into a community. Wording, especially in the media, does contribute to that dynamic, she said.

“Media representations are so negative,” she said. “It’s one of the ways these categories have been transformed in people’s minds. When you think of an immigrant or a refugee, the associations aren’t of someone who would bring about a change or do some great thing in the community. It’s always associated with a need.”

In that sense, at least, the problem lies less in the words used as in the weight they are given. If those in the throes of crisis are represented as shiftless, a threat to jobs, ignorant of cultural norms, and dangerous, then whatever word is applied to them will take on that meaning, too.

Public domain: Freedom House Syrian Refugees

Public domain: Freedom House Syrian Refugees

“I think that the terms refugee versus migrant are not the defining ones, but rather the portrayal of people coming to us,” Magdalena Schwartz, who has worked with refugees in Austria and Hungary , said in an e-mail. “So, if someone is treated like a criminal with bad intentions, it does not really matter if they are called migrant or refugee.”

That is true to the extent of how people navigate these labels as individuals. But where it begins to matter more is when those labels—negative connotations intact—are applied to large groups of people. Then the dangers of making sweeping generalizations are apparent. It’s harder to have compassion and concern for “a migrant,” or “a refugee,” than it would be for a fellow human being. And this only gets exponentially more difficult when contemptuous or disapproving overtones are applied to the meaning.

In the end, the words we choose do matter, but we can’t be such slaves to semantics that we allow unhealthy stereotypes to perpetuate. It is useful to have umbrella terms when communicating about the complex situation of those migrating into Europe. But officials, news organizations, and others who work in the realms of human migration must remember that they set a precedent for how these people are treated and how they see themselves. In that sense, it’s helpful to think on an individual scale and not reduce a human to a designation that only describes one aspect of their lives.

"We need to have more empathy. Nobody who is a refugee decided to come to this country as an adventure"

“Sometimes we need to look at the larger picture, but sometimes we need to look at the individual,” Madrid said. “We need to have more empathy. Nobody who is a refugee decided to come to this country as an adventure. It’s never that easy and there is so much more than we’re able to see at first glance. A label can’t fit their situations.”

REFERENCES

Edwards, Adrian. 2015. UNHCR Viewpoint. “Refugee” or “Migrant?” — Which Is Right? http://www.unhcr.org/55df0e556.html (accessed February 4, 2016).

Malone, Barry. 2015. "Why Al Jazeera Will Not Say Mediterranian 'Migrants'" Al Jazeera http://www.aljazeera.com/blogs/editors-blog/2015/08/al-jazeera-mediterranean-migrants-150820082226309.html (accessed January 29, 2016).

Taylor, Charlotte. 2015. "Migrant or Refugee? Why it Matters which Word You Choose" The Conversation https://theconversation.com/migrant-or-refugee-why-it-matters-which-word-you-choose-47227 (accessed January 30, 2016).

UNHCR. 2011. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. http://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10.html (accessed January 30, 2016).

UNHCR. 1992. Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees.

Jolie Breeden is the lead editor and science communicator for Natural Hazards Center publications. She writes and edits for Research Counts; the Quick Response, Mitigation Matters, Public Health, and Weather Ready Research Award report series; as well as for special projects and publications. Breeden graduated summa cum laude from the University of Colorado Boulder with a bachelor’s degree in journalism.