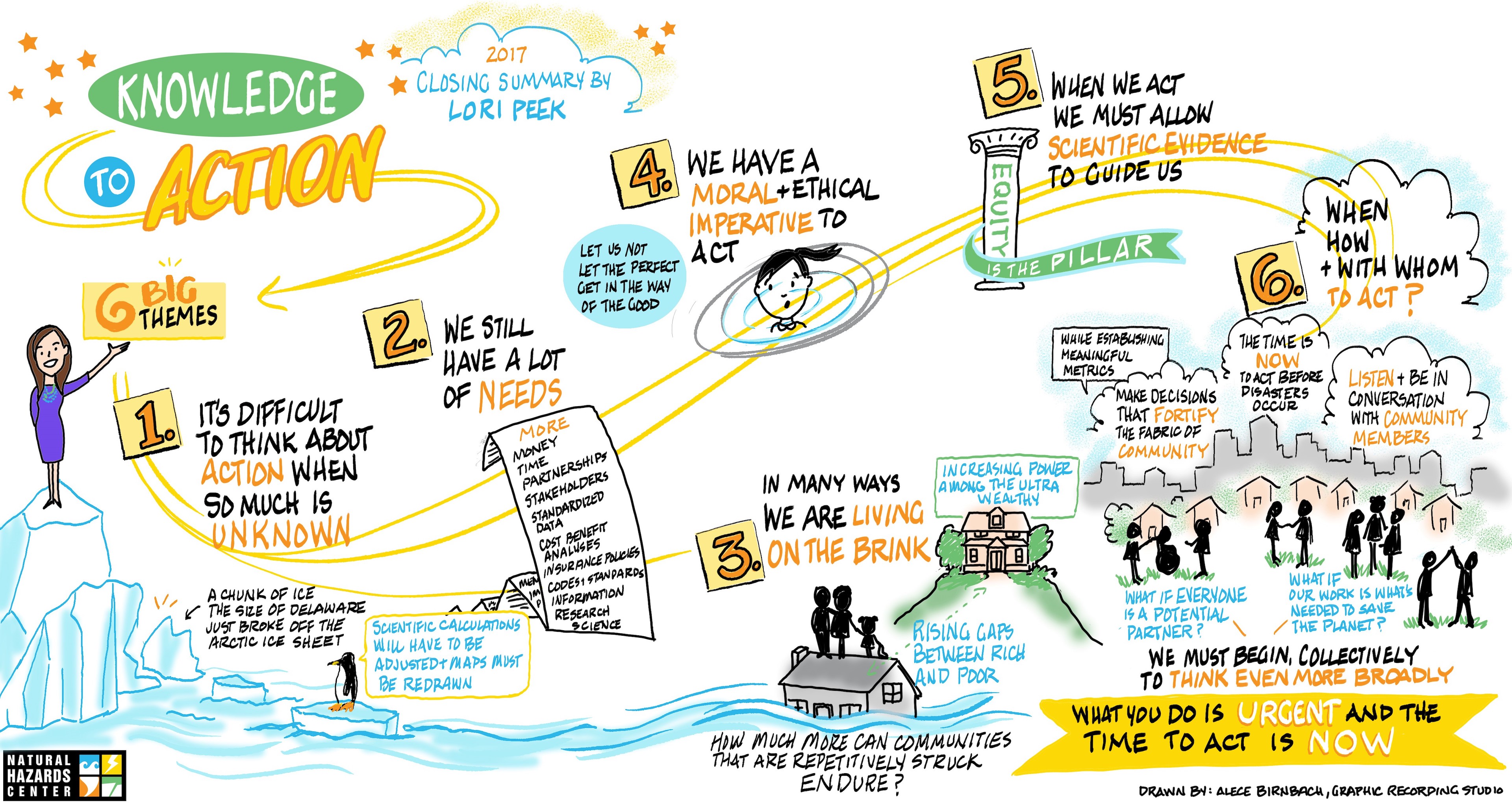

Graphic recording of the wrap-up of the 42nd Annual Natural Hazards Workshop. Image created by visual recorder Alece Birnbach.

Welcome to my first Director’s Corner post. With this new feature, my plan is to communicate more regularly and widely with members of our hazards and disaster community. In turn, my hope is to hear more frequently from you, so the Natural Hazards Center can be responsive to the big issues and challenges that you grapple with in your research and practice.

For this initial post, I’ve decided to share the closing remarks I delivered at the 42nd Annual Natural Hazards Workshop in Colorado. One of my primary responsibilities at this year’s Workshop was to listen to and learn from participants. I moved in and out of the breakout sessions so that I could get a sense of the nature and flow of the conversations. I also asked attendees to tell me what resonated with them and if they had learned anything that would change their research or practice.

Wednesday morning I woke up early (really early!) and began synthesizing and writing up the key ideas that bubbled up, especially as they related to our theme of Knowledge to Action. Below is a lightly edited version of the comments that I ultimately shared at the closing session of the Workshop.

What cannot be fully captured here is the immense gratitude that I felt as I looked out across our audience. It is clear to me, even during these turbulent times, that this community has continued the important work of reducing disaster risk every day. Thank you for all that you do, and thank you to those of you who were able to join us for the 2017 Workshop. It was a true gift to be in your presence.

Lori Peek, Director

Natural Hazards Center

Natural Hazards Center Director Lori Peek delivers closing comments and the 42nd Annual Natural Hazards Workshop on July 12, 2017. ©Jennifer Tobin, 2017.

Director’s Closing Remarks 42nd Annual Natural Hazards Research and Applications Workshop July 12, 2017, Broomfield, Colorado

In reflecting on our past four days together, I heard six big themes recurring throughout this Workshop.

First, I heard time and again across the sessions and in my conversations with you that it is really difficult to think about action when there is still so much that is unknown.

Rebecca Beavers of the National Park Service put it well. She said: “How do we begin to think about current and as well as future actions when the parameters are changing under our feet?” Rebecca made this observation just two days ago.

Just this morning we learned that a chunk of ice the size of Delaware broke off the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Scientific calculations must be adjusted and maps are going to have to redrawn because of this.

There is, indeed, still much that we don’t know.

A second big reoccurring theme was that we still have a lot of needs.

What do we need? I heard that we need:

More money.

More time.

More partnerships.

More stakeholders.

More standardized data.

More scalable data.

More cost-benefit analyses.

More insurance policies.

More codes and standards for various hazards.

More information on opportunities for action.

More information on barriers to action.

More research.

More science.

More science in government.

More mentoring.

More practitioners.

More imagination.

Gerry Galloway even noted that we need more political leaders with spine. The list goes on. The needs are real. And they are pressing.

This leads me to the third big theme of your workshop: In many ways, we are living on the brink. In his Larry A. Larson Association of State Floodplain Managers Foundation lecture, Dennis Mileti noted that with the rising gaps between the rich and poor and the increasing concentration of power among the ultra-wealthy, it is becoming all the more difficult to fight for sustainable climate adaptation and mitigation programs that may just save the planet.

And what does that living on the brink mean at the local level?

Gavin Smith, with all of the work that he and his team are doing in North Carolina following the devastation caused by Hurricane Matthew, invited us to ponder the following: “How much more can communities that are repetitively struck low by flood losses and other disasters, how much more can they possibly endure?”

The fourth big theme was this: Even though we know that we don’t know everything we need to know, and even though we don’t have everything we need, we have a responsibility to act. Nate Wood from the U.S. Geological Survey put it like this during his Sunday roundtable: “There are so many challenges facing our world. Let’s not let the perfect get in the way of the good.”

During our opening plenary session, Rong-Gong Lin II of the Los Angeles Times made a compelling case that we actually have a “moral imperative” to act in the face of mounting climate and environmental risks.

I want to pause for a minute and say something to all of you about this idea of there being a moral imperative to act.

When I hear those words, I want you to know that they are more than some abstract principle. When I think about a moral imperative, I think of the hundreds of millions of people across the globe that are struggling to cope with the ongoing and unfolding consequences of disaster. I see the faces of disaster survivors, and especially of children, whose lives have been interrupted and badly disrupted by disaster.

With this in mind, I want to tell you about an 18-year-old young woman named Samantha who lives in New Orleans. I met her in the course of my research. By the time I interviewed her, she had already experienced four major disasters in her short life.

Stop and let that sink in for a minute. She is 18-years-old. She has already survived four major, community-level disasters that have caused major disruption in her life.

Samantha was just 6-years-old when Hurricane Katrina devastated the U.S. Gulf Coast. That August of 2005, her mother had bought her a new pair of ballet slippers and she was supposed to begin dance classes on Monday, August 29—the day that Katrina made landfall. In reflecting on her life since then, she said this:

“Losing everything and having to start over, that has happened to me so many times, it just feels like I lost my childhood. And I guess Katrina was the hardest for me because it was so disruptive. I was supposed to start my ballet classes that Monday, but then I never did. So maybe I could have been a dancer or something? But now that opportunity is gone forever.”

When I think about having a moral imperative to act, I think about Samantha. I see her face. And I hear her voice.

I would guess that most of you in this room have similar stories.

We have a moral and an ethical imperative to act. Let us not delay.

The fifth major thing I heard was that when we act, we must allow scientific evidence to guide us, as well as opportunities for justice and equality drive us.

Flozell Daniels from the Foundation for Louisiana said that “equity is the pillar” for everything they decide to do. And Shannon Van Zandt, during her concurrent session, reminded us that “if you are leaving the most vulnerable segments of the community behind, you cannot logically and morally claim to be a resilient community.”

I think the Wednesday plenary panelists, who were discussing the ways that we might respond to vulnerable people and places, drove this theme home just perfectly.

Sixth, and finally, I heard you all talking about when to act, how to act, and with whom we should be acting.

When? The time is now, and the time to best act is before disaster occurs.

That means, as Nick Shufro from the Federal Emergency Management Agency said, there will need to be more dollars invested in mitigation and other activities designed “to root out risk and to encourage resilient design.”

How are we going to do this? Ray Bonilla of Kaiser Permanente said it beautifully in his keynote address. He argued that we are going to need to make decisions that at every turn “fortify the fabric of our community” while establishing “socially meaningful measures and metrics” that will allow us to know when progress has actually been made.

And then, there is “the who” when it comes to knowledge to action.

We heard a lot during this 42nd Annual Natural Hazards Workshop about partnering with communities that experience high levels of hazard risk. Partnering with communities that are recovering from disaster. Partnering with vulnerable communities. And, as David Prevatt, an engineer from the University of Florida, reminded us, at all moments, we must remember that that we must listen to and be in conversation with those community members.

There were so many important groups and constituencies identified during this workshop. But I would like to end with a challenge to all of us.

I think we must begin, collectively, to think even more broadly.

What if we woke up every day and realized that the work that people in this room do, it may just be what we need to save the people on this planet? How would that change our thinking?

How would it alter our practices if we thought of everyone as a potential constituent and beneficiary of the work that we do? What if we thought of everyone as a potential partner?

Because here is what is clear—we are not all equally at risk. But the risks that we are all facing are increasing by the day.

So please, whatever you take from this Workshop, please take this message that what you do is important. It is urgent. And the time to move knowledge into action is now.

Thank you for attending this Workshop and thank you for all of your contributions. This is your Workshop, and it is our honor at the Natural Hazards Center to have had the opportunity for over four decades to serve as the organizers and conveners of this meeting.

Thank you for your time. Thank you for your attention. And thank you for your contributions to society. Travel safely, and always, please take care of yourself and others.

With that, I declare your 42nd Annual Natural Hazards Workshop adjourned.