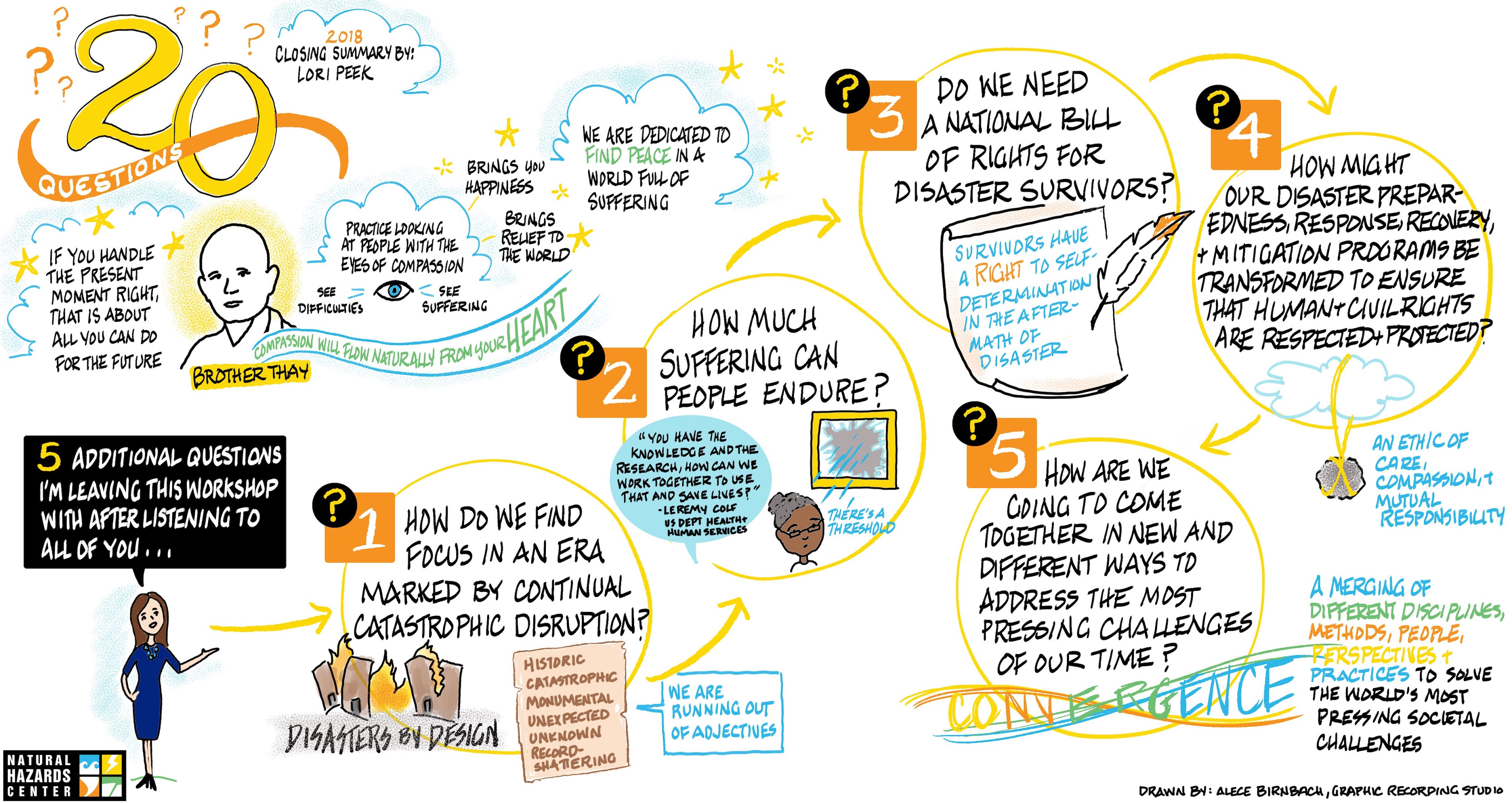

Graphic recording of the wrap-up of the 43rd Annual Natural Hazards Workshop. Image created by visual recorder Alece Birnbach, with the generous support of Impact360 Alliance.

Graphic recording of the wrap-up of the 43rd Annual Natural Hazards Workshop. Image created by visual recorder Alece Birnbach, with the generous support of Impact360 Alliance.

Welcome to the Director’s Corner. The Natural Hazards Center launched this feature last summer after the Natural Hazards Research and Applications Workshop as a way to allow for direct exchange and dialogue with the broader hazards and disaster community.

As I did last July, I’d like to use this forum to share my closing remarks from the Natural Hazards Workshop. During the Workshop, one of the primary responsibilities of the director of the Center is to attend all the sessions and add-on events in order to listen and learn from the participants. Then, on Tuesday evening after the barbecue, I retreated to my room and burned the midnight oil to draft the comments I would deliver at the close of the 43rd Annual Natural Hazards Workshop, which was focused on the theme of Twenty Questions: Looking for Answers to Reduce Disaster Risk.

With the theme of 20 Questions, attendees at the Natural Hazards Workshop focus on finding solutions to reduce disaster risk. ©Natural Hazards Center, 2018.

With the theme of 20 Questions, attendees at the Natural Hazards Workshop focus on finding solutions to reduce disaster risk. ©Natural Hazards Center, 2018.

I share these comments with you here as a summary of the meeting, and also as a call to action as we move forward together in this coming year.

It is a gift to serve alongside the team at the Natural Hazards Center, and it is our great honor to serve this community. We greatly appreciate those of you who were able to attend the meeting this year, and to those who were not there, we sincerely hope to welcome you to Colorado in the future. All, we ask that you please save the date for the 44th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop, which will be held July 14-17, 2019, and the Researchers Meeting, which will be July 17-18, 2019. Both events will be at the Omni Interlocken Hotel in Broomfield, Colorado.

Thank you for all that you do to reduce the harm and suffering of disasters and to promote social wellbeing. As always, I offer my deepest gratitude.

Lori Peek, Director

Natural Hazards Center

Closing Comments

More than 500 people gathered at the 43rd Natural Hazards Workshop in July 2018. ©Natural Hazards Center, 2018.

More than 500 people gathered at the 43rd Natural Hazards Workshop in July 2018. ©Natural Hazards Center, 2018.

This year our community has gathered together for what Ed Hecker of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has called our “52nd Week of the Year.” It is that special week that we hope informs and inspires the other 51 weeks.

On this 52nd week, at our 43rd Annual Natural Hazards Workshop, we have come together as one to engage with the theme of Twenty Questions: Looking for Answers to Reduce Disaster Risk.

In that spirit, I want to begin with a question that Krista Tippett—who leads the On Being interview series—asked of Thich Nhat Hanh during an interview titled “Being Peace in a World of Trauma.” Thich Nhat Hanh, who is also known widely as Brother Thay—or teacher—is a Vietnamese Zen master, peace activist, author of many books including The Miracle of Mindfulness, and was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize by Martin Luther King, Jr.

At the end of a long and meaningful interview, Krista Tippett drew the conversation to a close:

Ms. Tippett: I want to finish because I know I've taken a lot of your time. I want to ask you, this is from Fragrant Palm Leaves, which I know is a journal you wrote in the 1960s, but this is about Zen: “Zen is not merely a system of thought. Zen infuses our whole being with the most pressing question we have.” What are your pressing questions at this point in your life?

Brother Thay: Pressing questions?

Ms. Tippett: Mm-hmm. What are the questions you work through in your practice just personally, I wonder.

Brother Thay: I do not have any questions right now. My practice is to live in the here and the now. And it is a great happiness for you to be able to live and to do what you like to live and to do. My practice is centered in the present moment. I know that if you know how to handle the present moment right, with our best, and then that is about everything you can do for the future. That is why I'm at peace with myself. That's my practice every day, and that is very nourishing.

Ms. Tippett: And I wonder, living that way and practicing that way, does forgiveness become instinctive? Does there become a point where you no longer react with anger but immediately become compassionate and forgiving?

Brother Thay: When you practice looking at people with the eyes of compassion, that kind of practice will become a good habit. And you are capable of looking at the people in such a way that you can see the suffering, the difficulties. And if you can see, then compassion will naturally flow from your heart. It's for your sake, and that is for their sake also. In The Lotus Sutra, there is a wonderful, five-word sentence. “Looking at living beings with the eyes of compassion.” And that brings you happiness. That brings relief into the world. And this practice can be done by every one of us.

Thich Naht Hanh’s entire life has been dedicated helping to people to find peace in a world of suffering, anger, conflict, displacement, and forced separation. It strikes me that this is true of so many in this room as well.

In the spirit of being present and entertaining pressing questions, I would now like to raise five additional questions that I am leaving this Workshop with after listening to all of you.

The first question:

How do we find focus in an era marked by continual catastrophic disruption?

During the opening plenary at the Workshop, Adam Smith of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration—also known as NOAA—presented a number of disturbing trend lines related to rising billion dollar disaster losses across natural hazard types. After showing us the data, he said, “We are running out of adjectives for describing what is happening.”

Historic. Catastrophic. Monumental. Unexpected. Unknown. Record-breaking. Record-shattering.

We are running out of adjectives.

How do we find and maintain our focus in this time where decades of unsustainable land use planning, lax building code enforcement, rising social and economic inequality, and population growth in risky areas is coming home to roost? These are not natural disasters. These are disasters by design.

How do we find and maintain our focus in an age of weather whiplash and cascading catastrophes that lead us from one affected community to another, one deployment to the next, and yet another study before the previous one was even finished?

The second big question that I am leaving this Workshop with is this:

How much suffering can people endure?

Thich Naht Hanh, who was expelled from his native Vietnam as he worked for peace and refused to take sides, argues that suffering is a necessary precondition for compassion. Just as a lotus flower cannot bloom without mud, we as living beings may not experience understanding and compassion for one another without suffering.

But many of the leading minds in this community have taught us that there may be a threshold for human suffering just as there are thresholds when infrastructure shatters and buildings collapse. Barb Graff with the City of Seattle Emergency Management showed us so vividly that there is a point in an earthquake when unreinforced masonry buildings will not bend. They will break.

Similarly, there is also a breaking point beyond which the mind and the body may never be fully restored.

Victoria Thorpe of the Inter American University of Puerto Rico told a story in one of the sessions at this Workshop about suffering. She didn’t use that exact word, but the story she told was one of how, ten months after Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, she lives in an apartment that is still missing three windows. So every time it rains, she has a real mess on her hands. Victoria called that an "inconvenience."

But for her elderly neighbors, the missing windows and inoperable elevator were not just an inconvenience, they made living in that apartment building inconceivable. Unbearable. Unlivable. They were running out of adjectives and so they moved away.

According to researchers from Harvard University in a recently published study in the New England Journal of Medicine, perhaps as many as 4,600 Puerto Ricans succumbed all together. They lost their lives in the months following Hurricane Maria. Most of those deaths were due to delayed medical care related to hospital closures and power failures. Leremy Colf from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services called us to action on Sunday evening. He asked, “You have the knowledge and the research, how can we work together to use that to save lives?”

The third big question I am leaving here with is this:

Do we need a national bill of rights for disaster survivors?

John Henneberger of Texas Housers – Texas Low Income Housing Information Service, opened this Workshop on Monday morning with a keynote address that was a call to our moral and collective conscience. He argued—and I quote—that “while the specific programs for recovery vary from place to place, survivors everywhere need the opportunity to exercise choice on where they will live, how their neighborhoods will be restored, and how their needs and desires will be heard.” They have a right to self-determination in the aftermath of disaster.

Tuesday morning, Jacqui Patterson of the NAACP reminded us that we have certain inalienable human rights and specific civil rights that could inform our mitigation policies and programs and our disaster risk reduction activities.

That then brings me to the fourth question:

How might our disaster preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation programs be transformed to ensure that human and civil rights are respected and protected?

I believe that this would require that every policy and program be read through a justice and equity lens and that we adopt what Dick Krajeski of the Lowlander Center refers to as a total ethic of care.

Now I want to pause for a minute and acknowledge how lofty this all is. Lisa Corbly of Multnomah County in Oregon told me at lunch on Monday that sometimes when she is at meetings like this that it is important to “tie rocks to the clouds” to help make some of the most lofty ideas concrete. So let me please try to do that right now.

What does an ethic of care, compassion, and mutual responsibility actually sound like? Can we tie a rock to that cloud?

Let us start by examining a message that is not rooted in an ethic of care and compassion.

You are on your own.

We are not coming to get you.

We cannot make it to every disaster so you better be ready to fend for yourself.

Let me try that again, but this time rooted in what I perceive to be an ethic of care.

Decades of research have taught us that first responders actually cannot get to the scene of every disaster. With that in mind, we ask: Who do you love? Who do you care about? Who are you responsible for? Could you work together to get a plan to ensure that you are safe until we—the emergency responders—can get to you? Because trust us. We prepare. We train. We want to help. But we know we can’t be everywhere at once and so we are asking for your help and for us to work together to make this community safe.

It is the same message. The same message…

Jeannette Sutton, Sophia Liu, and the other risk communication experts out there: I know that second message won’t fit in a short 90-character Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA). But if we could figure out how to root a WEA message in an ethic of care, I bet this community could work together to also ensure that every program, policy, and practice involved a deeper sense of compassion and mutual responsibility.

This leads me to my fifth and final question.

If we are going to do this—if we are going to heed the warnings we have heard year after year at this Workshop and respond to the ever more urgent calls to action—how are we going to come together in new and different ways to address the most pressing challenges of our time?

The National Science Foundation and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine refer to this coming together as a convergence, or a merging of different disciplines, methods, people, perspectives, and practices to solve the world’s most pressing societal challenges.

Next year, on our 52nd week, at the 2019 Natural Hazards Workshop, we will focus on the theme of convergence. We will explore how we are coming together to study hazards and disasters, to apply the knowledge generated, to help one another, to build individual and collective capacity, to implement meaningful policy, and to envision future states that lead to reduced disaster risk and more just and equitable outcomes.

I am already looking forward to seeing you at next year’s Workshop, which will be held July 14-17, 2019. For right now, however, I stand in front of you, anchored in this moment and filled with gratitude for all that you do.

Please take care of yourself and others.

With that, I declare your 43rd Annual Natural Hazards Research and Applications Workshop, adjourned.