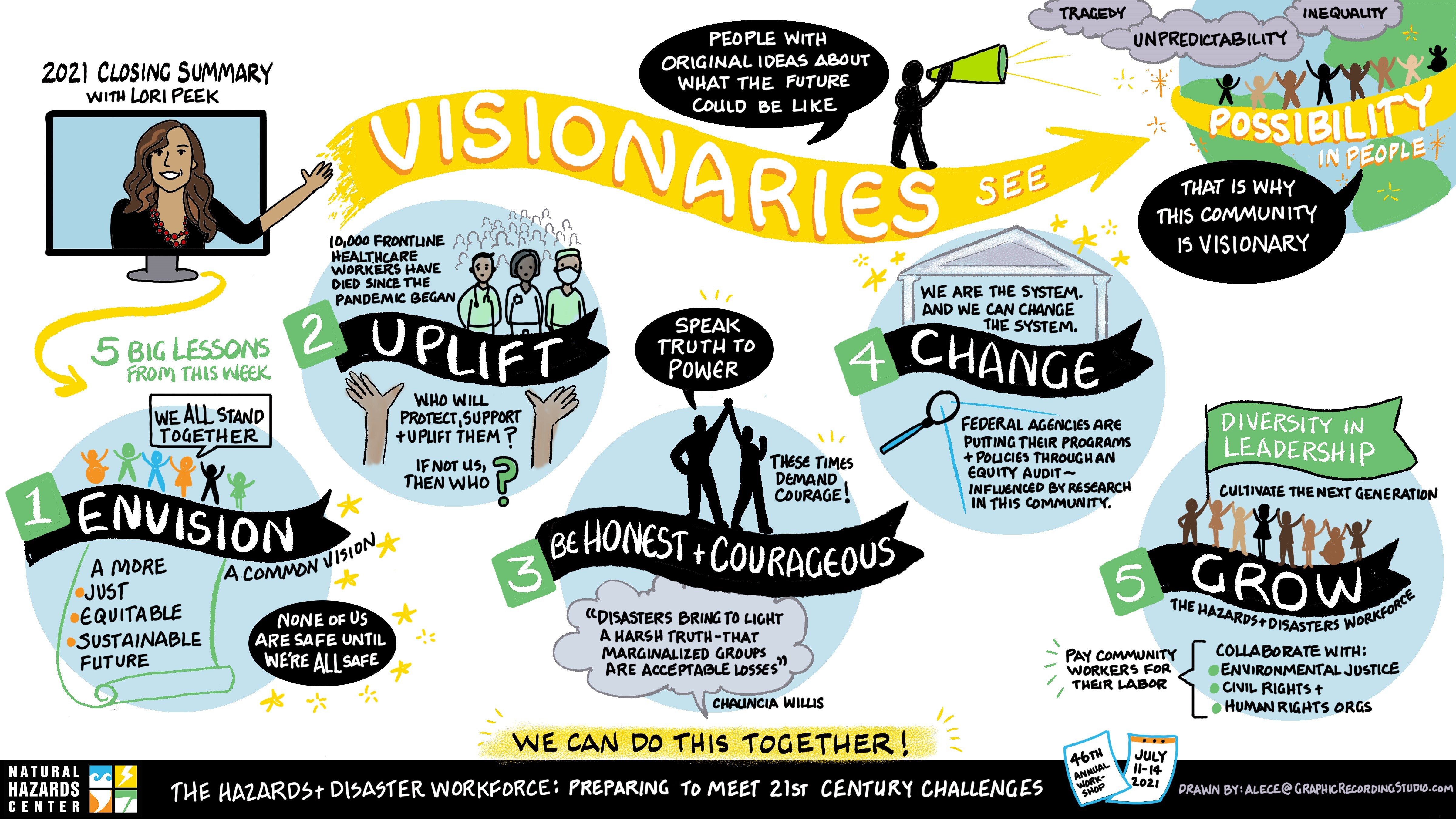

Graphic recording of the wrap-up of the 46th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop. Image created by visual recorder Alece Birnbach of the Graphic Recording Studio.

Graphic recording of the wrap-up of the 46th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop. Image created by visual recorder Alece Birnbach of the Graphic Recording Studio.

This is the 46th year that the director of the Natural Hazards Center has issued a summary and call to action at the end of the annual Natural Hazards Research and Applications Workshop.

What this means in practice is that to get a sense of the meeting, I split my time evenly between every session. Then, on the last day of the Workshop, I wake before the sun has graced the sky to write these closing comments. As has now become tradition, I am sharing the lightly edited version in this latest edition of the Director’s Corner.

Before proceeding, though, words of thanks are due to all those who attended this year’s Workshop. While the Natural Hazards Center has the honor of organizing the program, it is your meeting because you are the ones who make everything come to life. Even though we remained online this year due to the ongoing pandemic, you still showed up through your contributions and engagement with one another.

With more than 790 registrants, this was the second largest Workshop in our history—only surpassed by last year’s registration numbers. While we are eager to return to an in-person Workshop in July 2022, we will also ensure that the important lessons we learned from our virtual Workshops in in 2020 and 2021 stay with us. For instance, it was clear that the online environment created many additional opportunities for access and inclusion. As we begin planning for next year’s Workshop, we will keep these lessons at the forefront of our minds. We hope you will save the dates and join us.

Now, I am pleased to share the closing comments from 2021 Natural Hazards Workshop with you. The summary below synthesizes some of the key insights we reached from exploring of this year’s theme of The Hazards and Disaster Workforce: Preparing to Meet 21st Century Challenges.

Thank you for the work that you do. Please take care of yourself and others.

Lori Peek, Director

Natural Hazards Center

Closing Comments

Visionaries.

Visionaries are people with original ideas about what the future could be like.

Visionaries are people, as Lalrinpuii Tlau of GeoHazards International said, “who become aware of risks, and then start thinking about solutions.”

Visionaries.

That is who you are.

You look out at the world, and you see it in all of its complexity; its unpredictability; its inequality; its tragedy.

But you also see its possibility because you see the possibility in people. That is why this community is visionary.

For more than four decades at this meeting, we have mostly looked outward. We have assessed programs, policies, places, and people. But this year, in our 46th year, we turned that mirror on ourselves. Not in a self-serving way, but in a self-reflective way.

We are only two decades into this century, and we’ve got almost 80 years to go. Are we ready for what is coming? Do we have the people that we need to respond to the power imbalances and the political and economic injustices that are placing this planet in further peril?

After listening to all of you this week—listening to the visionaries out there—I feel more reassured than ever that we can do this together.

Here are five big lessons that you generated this week about what our hazards and disaster workforce needs to confront rising 21st century challenges.

Number 1: Envision

Even as the demands and pressures of today mount, we must continue to carve out the time and space to envision a different future. A future that is more just, equitable, and sustainable. One that puts science and morality on the same plane and sees them as inseparable. One where we live with the recognition that none of us are safe until we are all safe.

During the Tuesday plenary session, a global team of visionary practitioners from GeoHazards International, or GHI, shared a set of key principles for how we can collaborate with underserved communities at extreme risk to disaster to envision a different future.

When GHI works in a community, they stand beside the local leaders as they stand before some of the world’s most vulnerable structures. They look to the left, and they see one vision—one potential future—where the school they are assessing collapses into rubble in an earthquake, killing every child and teacher inside. But then they look to the right, and they work closely and respectfully with local practitioners to identify how to relocate, rebuild, or retrofit that building to save lives and to ensure that the heart of the community remains intact, even when disaster strikes.

Number 2: Uplift

To envision a different future is vital and necessary work. But, as Dontá Council of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta underscored, “this work can be mentally, physically, and spiritually exhausting.”

And, as medical doctor Thomas Kirsch gravely reminded us, the work can also be deadly. He estimates that perhaps as many as 10,000 frontline healthcare workers in the United States have died since the pandemic began, representing what is likely “the greatest healthcare workforce tragedy in our national history.”

He challenged us to consider: Who will protect, support, and uplift those workers? If not us, then who?

It is clear that the members of this community are taking responsibility for identifying our gaps, weaknesses, and missing pieces and people, so we can do better work. This is going to require that we support and uplift one another.

Yesterday morning, during the Gender and Disasters Roundtable, Alice Fothergill of the University of Vermont told a moving story about why the roundtable was established here at the Natural Hazards Workshop 24 years ago. That group started meeting here because a number of visionaries including Barb Vogt, Kristina Peterson, Dick Krajeski, and Bill Anderson, among others, recognized that there were far too few women in this field. They endeavored to create a space to uplift and advance gender in this realm. That small morning meeting has now grown into the powerful global Gender and Disaster Network.

That is how we identify gaps and then begin to uplift one another.

Number 3: Be Honest and Courageous

To do this work, we have to be honest not just about how we are doing as a hazards community, but also about how we got into this disaster loss spiral that we are trapped in.

This isn’t just about vulnerable people. As Kim Mosby of the Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies emphasized, this is about structures and systems that were intentional about creating the unequal effects that actively render Black, Indigenous, and other persons of color, as well as women and others at the margins, vulnerable.

Chauncia Willis, in her opening keynote address, put it flatly: “Disasters bring to light a harsh truth—that marginalized groups are acceptable losses.”

To speak these truths takes courage and as Chauncia also made clear, speaking truth to power can come with dire personal and professional consequences.

But these times we are in, they demand exactly this kind of courage.

Number 4: Change

Julianna Valenzuela, a recent graduate of Colorado School of Mines, said that “If what we envision is not possible today, in our current system, then we need to change the system.”

I know that can feel easier said than done, but as Raj Pandya of the Thriving Earth Exchange underscored, “We are the systems and institutions.” That means we can change them.

Right now, federal agencies are putting their programs and policies through an audit to advance racial equity and support for underserved communities. This is not happening by chance. It is happening by design, and these audits are being influenced by research in this community that has—for decades—pointed to inequitable, unjust, and unacceptable post-disaster outcomes that leave the most vulnerable even further behind.

We are the system. And we can change the system.

Number 5: Grow

If we are going to not just survive this century, if we are going to have the opportunity to thrive, we are going to have to grow the hazards and disaster workforce.

Our conversations this week made clear, however, that there are simply not enough of us to mount a defense—let alone an offense—against the existential crises that we currently face.

Lakisha Woods from the National Institute of Building Sciences argued that we need to grow the workforce through cultivating an entirely new generation of leaders, with a special focus on increasing the number of women and people of color in positions of power. As Lakisha observed, “This kind of shift in diversity in leadership can help change everything.”

Why does diversity in leadership and throughout our workplaces matter so much? Because as Kimberly Mills from the Virgin Islands Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities underscored, “The thing about diversity is that when it is present, everyone benefits, and when it is missing, everyone suffers.”

We need a larger, more demographically and functionally diverse workforce, and we need more boundary spanners who are trained to work across disciplinary siloes. We also need to continue to build our coalitions with other groups that may not be operating directly in the hazards space but are working on the root causes that turn natural hazards into disasters.

As we heard in the closing plenary session, this means that the hazards and disaster community will need to work more frequently and intentionally with environmental justice, human rights, climate justice, and civil rights organizations. And, as Earthea Nance of Texas Southern University called for, we need to make sure that those collaborations are supported institutionally and that community workers are paid for their labor.

Changing this tide isn’t going to just take more of us. It is going to take all of us. This is a daunting task, but as Hari Kumar from GeoHazards International shared with us, “Mitigation is the best work. It may not get the funding or attention it deserves, but let us keep our shoulders to the wind.”

As you go forth with this work, please remember to take care of yourself and others.

With that, I declare your 46th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop adjourned.