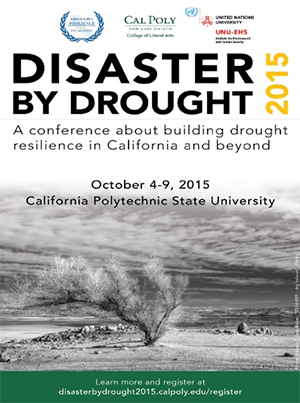

After three consecutive years of drought, Laguna Lake in San Luis Obispo, California, is completely dry. ©Ryan Alaniz, 2015.

After three consecutive years of drought, Laguna Lake in San Luis Obispo, California, is completely dry. ©Ryan Alaniz, 2015.

By Laura Olson and Ryan Alaniz

In August 2015, during one of the longest periods of drought in California history, I turned on my kitchen faucet to make my ritual morning coffee. Not a drop flowed from the tap and I caught my breath—our well was dry. Although I and my colleague Laura Olson explore drought academically, my immediate reaction was one of dread and panic. Like billions of people across the planet, my family was now water-stressed. And as a small farmer, our family ecosystem—including 22 goats, 40 chickens, a bee apiary, and greenhouse, garden, and small orchard—was without its sustaining lifeline. I had become a yet another victim of drought.

What we do now will shape our water future. Vulnerability to water scarcity is growing across the planet. In the United States, the impacts of drought may depend on how well local, state, and federal entities collaborate on mitigation, response, and recovery related to future water scarcity. The Fourth National Climate Assessment predicts future droughts will increase in length and severity as higher temperatures increase evapotranspiration and decrease soil moisture.

In California, the fifth largest global supplier of food and agricultural products, the 2012-2016 drought was the worst in 1,200 years, hitting agriculture especially hard and causing concern among state and national leaders. As uncharacteristically high record temperatures gravely stressed state water supplies, the governor declared a state of emergency and enacted mandatory water reduction measures for households statewide—but it’s agriculture that accounts for 80 percent of the state’s water consumption, and the agricultural industry was not subject to any water conservation measures. So while the state of emergency triggered some federal aid, discouraged water waste, and streamlined government processes, the larger issues related to agricultural water use and water rights in the American West were too politically contentious to overcome.

Measures to tackle drought are consistently too little, too late. Unlike the unexpected shock of tsunamis, earthquakes, and flash floods, the slow onset of water scarcity is easily ignored or tabled until the crisis escalates. Similarly, proactive mitigation strategies to address predicted droughts are rarely implemented in a timely way. Much like Aesop’s fable of the grasshopper and the ant, in which the lazy grasshopper sings the summer away while the industrious ant prepares food stores for winter, the value of early action is recognized too late, and our institutions and society are left vulnerable to water scarcity due to our lack of planning and the dismissal of swift remediation measures.

Disaster by Drought Conference Participants ©Laura Olson

Disaster by Drought Conference Participants ©Laura Olson

In response to these challenges, California Polytechnic State University (Cal Poly), the United Nations University Institute for the Environment and Human Security, and the Munich Re Foundation partnered on a Disaster by Drought Summit in 2015 that brought scholars from across the globe to California to examine the implications of extreme drought and share their knowledge about drought interventions at the level of policy and practice . Products from this workshop included a Federal Policy Brief submitted to the National Security Council, and a State Policy Brief which went to the California State Legislature. These documents recommended changes to policy frameworks, institutional arrangements, and drought adaptation practices. While the briefs have been recognized by the White House and adopted by the United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security, the knowledge is often not enough to shape sound policy.

Drought management in the United States is not proactive. The nation’s relief measures, mitigation strategies, and efforts to protect water resources need improvement—our toolset and level of preparedness is seriously deficient. Comprehensive reviews of federal government drought policy and programs, such as the National Drought Policy Commission report to Congress in 2000 have all come to the conclusion that an overarching federal drought policy does not exist. Instead, drought management is ad hoc and disparate drought policies and programs are implemented individually without a lead federal agency designated to ensure the coordination of relief efforts. Despite repeated calls to reform the U.S. drought management system, fragmented programs and funding continue to cause patchy and inconsistent relief, gaps in service, and slow and inefficient responses. Our emergency management system is equipped to handle drought the way it does other natural hazards, but treats droughts differently, despite evidence that the economic, environmental, and social consequences of drought rival quick-onset disasters.

Failure is no longer an option. Attempts to move the country towards the adoption of a coherent national drought policy go back to the National Drought Policy Act of 1998 , and have not produced the desired results. We cannot wait 22 more years to effect these much-needed changes. Years of consecutive drought are likely to continue given predictions of extended droughts and more arid baseline conditions in the United States. The possibility of mega-droughts and dwindling water resources will challenge existing policy regimes and require us to rethink the current policy landscape. Without concerted action to prime the policy pump, its likely our well of options will run dry.

Laura Olson is a distinguished affiliate professor of emergency management at Jacksonville State University and also teaches at Royal Roads University School of Humanitarian Studies and the Georgetown University Disaster Management program. She has 18 years of experience leading recovery, risk reduction, and climate adaptation initiatives across the globe. She has worked with governments, non-governmental organizations, United Nations agencies, and impacted communities on resilience and capacity-building after disasters.