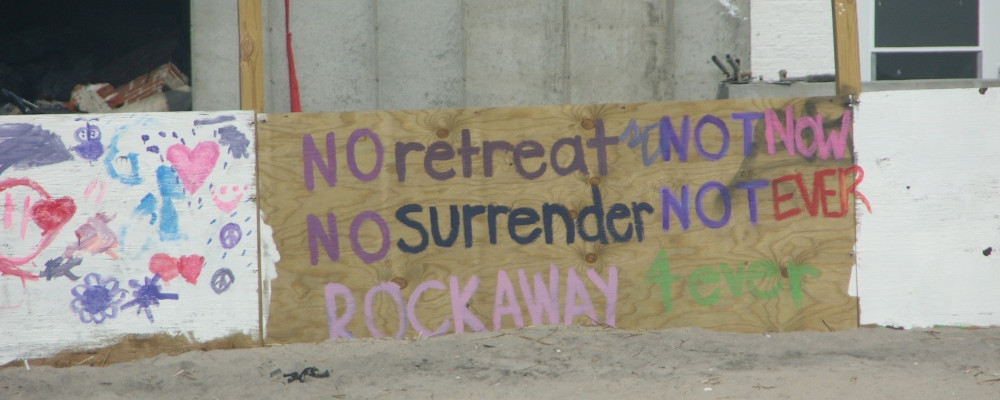

A declaration written on boarding after Hurricane Sandy in Rockaway, New York. © Anamaria Bukvic, 2013.

A declaration written on boarding after Hurricane Sandy in Rockaway, New York. © Anamaria Bukvic, 2013.

The devastation of Hurricane Sandy caught many East Coast residents by surprise. The gravity of the disaster, however, truly came into focus months later when the reality of slow recovery—hampered by weather, the many impacts of the storm, and bureaucratic red tape—started to sink in. The compound challenges faced by residents, including psychological trauma, property loss, and the inability to resume day-to-day life, caused a number of community members to wonder if relocating away from high-risk areas might be a better option.

Relocation has been increasingly discussed as a possible adaptation and hazard mitigation strategy for households and communities with high physical vulnerability to repetitive coastal hazards. The discourse about whether to move away from risk or to coexist with it has been extensively explored in the context of natural hazards and disasters. One of the key takeaways from these conversations is that the decision to relocate is highly contextual, complex, and shaped by many personal and place-based considerations.

Understanding the priorities that influence the willingness to consider relocation is paramount to developing proactive policies and programs that would ensure that the relocation process is efficient and equitable. Currently, one of the main financial mechanisms that provides support for permanent relocation, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, only does so after a major disaster is declared and only if properties meet strict eligibility criteria based on the frequency and extent of damage.

A declaration written on boarding after Hurricane Sandy in Rockaway, New York. © Anamaria Bukvic, 2013.

A declaration written on boarding after Hurricane Sandy in Rockaway, New York. © Anamaria Bukvic, 2013.

Support for voluntary relocation varies among residents based on their financial concerns, risk perceptions, experience with chronic flooding and disasters, attachment to home and place, and social embeddedness in their neighborhood and community. These considerations and how they are prioritized often change after residents experience a major disaster.

It’s important to identify personal and situational factors that influence the decision to permanently relocate if we’re to develop more productive relocation programs. To better understand this issue, a total of 125 surveys were collected five months after Hurricane Sandy in the eight New Jersey communities with the highest levels of structural damage. My research suggests that the primary reasons influencing the willingness to consider relocation among Hurricane Sandy-affected homeowners were:

Level of stress associated with rebuilding, recovery, experiencing recurrent hazards, filing insurance claims, and the loss of personal belongings. Relocation was not perceived as stressful, either because residents considered it less discomforting or because they did not consider it at all.

Financial aspects such as increases in insurance rates, filing assistance claims, and tax increases.

Repetitive exposure to coastal hazards and disasters that increase anxiety, incur damage expenses, and disrupt livelihoods—eventually pushing residents past their tolerance level and prompting them to permanently relocate.

Change in community profile after disasters, possibly attributable to slow or inadequate recovery. Such changes might include a decrease in available services and amenities, deteriorated school systems, increased crime, or the closure of businesses.

Considerations that were the least important when considering relocation in Hurricane Sandy-affected communities included moving together with neighbors, friends, and family and relocation incentives, such as providing similar housing in a new location, free legal services, and assistance with finding a new job elsewhere. Survey respondents preferred an individualistic approach to the relocation reflecting their personal preferences and values. Those who had shorter residence in the household were also more likely to support relocation because of concerns about tidal inundation and frequent flooding, perhaps because they were not used to dealing with this problem.

Understanding concerns, priorities, and preferences related to potential voluntary relocation after major disasters—and how they differ among diverse coastal populations—is key for developing effective and equitable relocation policies and programs. This research shows that economic factors are a major concern for most homeowners challenged by coastal disasters. Transparency about the financial consequences of hazards and disasters, the full cost of living in high-risk coastal areas, and the investment needed for adaptation and hazard mitigation effectively communicate the level of risk and may influence decisions about whether to stay in place or relocate.

This suggests that financial incentives or disincentives could play a role in helping homeowners better understand their options. In addition, proactive community dialogue about evacuation options, recovery expectations, available support, and uncertainty about frequency and duration of future hazard exposure could lessen other impacts, such as disaster-related anxiety and stress. As a growing number of coastal residents become aware of slow-onset hazards such as sea level rise and more pervasive tidal flooding, it is important to emphasize the compounding of risk and discuss all future scenarios to allow residents to prepare mentally, financially, and logistically for possible relocation.

Anamaria Bukvic is an associate professor of geography at Virginia Tech. Her research focuses on coastal adaptation, resilience, and human mobility. Many of her publications and projects explore the impacts of flooding on coping capacity and relocation in coastal communities. She was a Fellow of the 2019 Early Career Faculty Innovator Program at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the associate director of the Center for Coastal Studies at Virginia Tech.