James Kendra and

James Kendra and

Tricia Wachtendorf, 2016

ISBN: 9781439908211 (paperback)

182 Pages $24.95

Temple University Press

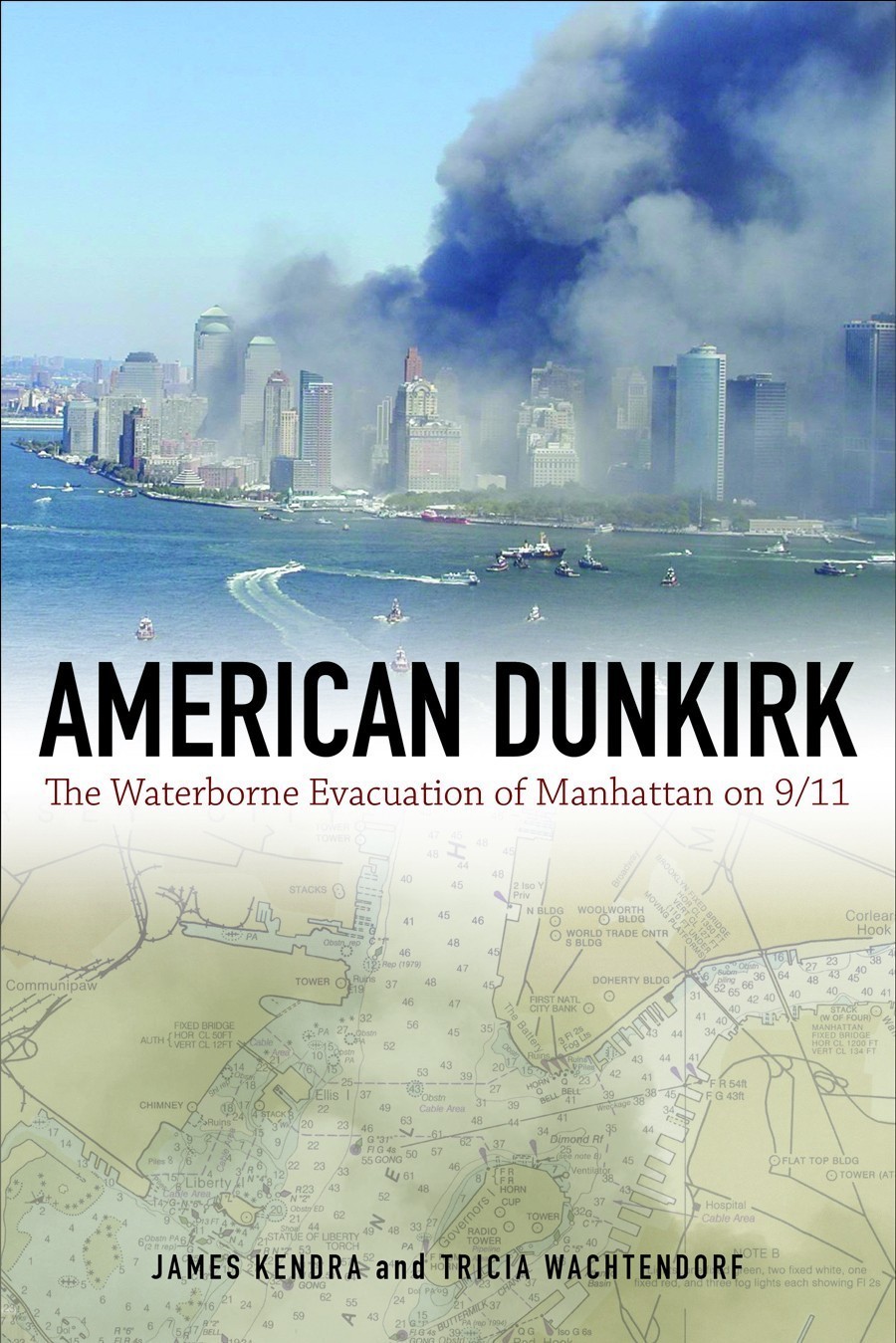

THIS BOOK ABOUT the unplanned yet successful waterborne evacuation of hundreds of thousands of people stranded in lower Manhattan after the collapse of the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001 was published just in time for the 15th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks.

The authors, James Kendra and Tricia Wachtendorf, both directors of the Disaster Research Center at the University of Delaware, began their study of the multi-organizational response immediately after the attacks. When they arrived in New York City on September 13, 2001, their emergency management contacts allowed them access to response meetings, operation centers, staging areas, and even ground zero. While in the field they became particularly interested in the creativity and improvisation of those involved in maritime response operations in the immediate aftermath of the disaster.

A year later, they began an interview project and spoke to 100 people directly or indirectly involved in the waterborne evacuation, including mariners, waterfront workers, harbor pilots, Coast Guard officials, and emergency response workers. These interviews were supplemented by 18 interviews that are part of an oral history project at the South Street Seaport Museum in Manhattan. In addition, the authors reviewed hundreds of photographs, newspaper articles, news accounts, e-mails, and video footage. They used these sources of information to triangulate the information they heard in their interviews. With this approach, they have brought together the most comprehensive dataset available on the waterborne evacuation and their book, American Dunkirk, is a careful analysis of this dataset. In this book, of particular interest to students and faculty of emergency management, the authors weave together the voices of ordinary people who did extraordinary things under challenging circumstances. They then use this research to criticize the Incident Command System (ICS) and suggest a new approach to disaster management.

A Dunkirk-like operation?

For those who aren’t World War II history buffs, it might be useful to briefly discuss the Dunkirk evacuation of 1940 (a discussion unfortunately absent from American Dunkirk).

During the early stages of the Battle of France (1940-1944), Allied troops in Dunkirk found themselves surrounded by the German Army. A window of opportunity to get out of this precarious situation presented itself on May 24, 1940 when Hitler ordered German forces to cease their advance on the French port. A day later, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the British Expeditionary Force to evacuate troops to Britain.

Since the docks in Dunkirk harbor were too badly damaged to be used, the Royal Navy searched nearby shipyards for suitable boats that could transport soldiers from the beaches to destroyers and other large vessels docked further out at sea. In addition, they put out an emergency call for citizens to make their vessels available. That call was heeded by hundreds of boat owners, some of whom also volunteered their services as captains. During the eight-day evacuation operation that followed, troops were ferried from the beaches to larger ships by a makeshift flotilla of 861 merchant marine boats, fishing boats, lifeboats, and even recreational vessels. Altogether, more than 336,000 British, French, Belgian, Dutch, and Polish soldiers were rescued.

Unfortunately, Hitler’s halt order only lasted for three days. By May 27, German heavy artillery were firing high-explosive shells into Dunkirk as Luftwaffe bombs reduced the town and its surroundings to rubble. More than 230 vessels were destroyed and approximately 5,000 soldiers and 1,000 civilians were killed.

While the parallels between the evacuation events are evident—for example, both operations brought boats of all descriptions together to save thousands of people—there is also a glaring difference. The Dunkirk evacuation was centrally organized, while the evacuation of lower Manhattan was much more spontaneous. And that improvised, creative, and self-organized nature is exactly what is central to American Dunkirk.

“We just wanted to help”

The authors describe how, after the first plane struck the north tower of the World Trade Center complex, many local mariners acted independently and took it upon themselves to navigate their boats towards the disaster area to pick up evacuees and drop off supplies and emergency personnel. Some of these mariners sought permission from the Coast Guard, which initially instructed vessels to stand by. By the time the Coast Guard issued a request for all available boats to participate in the evacuation, the operation was already in full swing. In fact, the authors state that approximately two-thirds of the people they spoke to hadn’t heard the official call (radio channels were flooded and many operators switched their radios off) before responding or were already responding or preparing to respond when they did hear it.

At the time of the attacks, there was no official plan for a waterborne evacuation of Manhattan in place. Instead, the effort was ad hoc and emergent.

“We moved about 30,000 people on our six boats,” the book quotes Peter Cavrell, senior vice president of sales and marketing for Circle Line, as saying. “It wasn’t any kind of coordinated effort. We just started doing it.”

Other mariners that were interviewed also said no one directed them. They “just wanted to help” and “did what they had to do.”

What unfolded in the next few days was rather remarkable. No significant accidents occurred during the evacuation, even though evacuees were boarding vessels that weren’t designed for passengers from locations that weren’t meant for transferring people and conditions were stressful and uncertain. The authors describe the evacuation as “an example of individuals and organizations learning and acting under conditions of extreme environmental stress: forming new relationships, suspending existing procedure and developing new ones, and making decisions based on ever-shifting and ambiguous information.”

With seeming effortlessness, the mariners involved in the evacuation took on the roles of emergency responders and those roles evolved with the changing needs at ground zero. First their vessels carried passengers. Then they brought medical teams, dogs, food, water, and even body bags. On the evening of September 11, dinner cruise boats were loaded with gurneys to make a triage and treatment area. These boats also served as dining halls and rest stations for exhausted firefighters and rescuers. According to the authors, all of these activities stemmed from moment-to-moment interpretations of what was happening in the environment and what could be done with the people and resources available.

So what made these improvised activities effective? A first requirement, according to the authors, was a strong local network and a sense of community. Mariners in the New York harbor belong to a close-knit group who are familiar with each other’s strengths, weaknesses, and capacities. A second requirement was a deep understanding of the local environment. Many mariners who were involved in the evacuation had years of experience and knew the Manhattan waterfront and waterways well. Along with this experience, came a myriad of skills and traits, which mariners aptly deployed during the evacuation operation.

Some of those traits are especially worth mentioning. The authors note that in the maritime community there is a strong imperative toward rescue. In fact, at sea shipmasters are compelled by statute to help vessels in distress if they can do so without serious danger to their own vessel. This means members of the maritime community are used to taking risks to help others. Another trait that proved useful during the response operation is mariners’ hypervigilance and attention to detail. They are taught to be watchful and alert for the unusual, because at sea, overlooking a seemingly small detail (such as not securing cargo properly or attending to a rattling sound in the engine) can have serious consequences.

The final requirement, according to the authors, is a willingness to bend the rules and procedures whenever necessary. The testimonies brought together in American Dunkirk emphasize that the mariners who responded did not take unnecessary risks. Instead they took risky actions with “a calculated awareness of the consequences of breaking the rules versus the urgency of the situation.”

A newish concept of disaster management

Kendra and Wachtendorf conclude that all of the above observations point to a particular concept of disaster management, a concept that sees “plans as tools rather than scripts” and “tilts more toward effectiveness than efficiency and encourages the affected population to improvise and be creative.” This challenges the Incident Command System, the concept that currently prevails in the United States. ICS is a standardized hierarchical approach to the command, control, and coordination of emergency response.

Based on their evacuation research, the authors propose an approach that redefines disaster activities as allied modules instead of a fully connected network. In doing so, they draw on the Emergent Human Resources Model (EHRM), which describes the involvement of disaster response participants as “flexible, malleable, loosely coupled, organizational configurations.” The authors take this idea one step further by arguing that these “loosely coupled configurations” don’t respond to one single event, but rather to individual pieces of this event. And this approach is what makes an improvised disaster response possible and manageable.

Kendra and Wachtendorf are not alone in their criticism of the ICS’s command-and-control aspect; many other social scientists also find it unsatisfactory. First responders and emergency managers, however, tend to be strong supporters of ICS—primarily because they are often held legally and morally accountable for their responses, according to the authors. Taking this into account, they suggest that ICS might be fine for “those organizations that can be captured reasonably within its structure.” Nevertheless, they also recognize that there are organizations that cannot be forced into that model and to address this issue they propose an open ICS like system that functions in concert with an EHRM model.

It’s a shame American Dunkirk—which is an excellent case study of the waterborne evacuation of Manhattan and makes a strong argument for the need for planning and organizational improvisation in disaster—didn’t come out sooner. Still, its release on the 15th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks is a powerful way to remember the heroic and selfless roles played by mariners in the evacuation operation.

Elke Weesjes Sabella is former editor of the Natural Hazards Observer. She joined the staff in December 2014 after a brief stint as a correspondent for a United Nations nonprofit. Under her leadership, the Observer was revamped to a more visual format and one that included national and international perspectives on threats facing the world. Weesjes was the editor of the peer-reviewed bimonthly publication United Academics Journal of Social Sciences from 2010 to 2013.

Weesjes Sabella also worked as a research associate for the Center for Disaster and Risk Analysis, formerly located at Colorado State University (although no longer active). In that role, she collected and analyzed data and translated research findings for a broader audience. She played a central role in finalizing the Disaster Preparedness among Childcare Providers in Colorado project, which examines all-hazards preparedness in daycares and in-home childcare across Colorado. She co-authored the report based on the first stage of the project, which was funded by Region VIII of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Weesjes Sabella specializes in cultural memory and neighborhood/community change in times of acute and chronic stress. She has published articles on the impact of drought on farming communities in Kansas, the effects of Superstorm Sandy in Far Rockaway, Queens, urban renewal in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, and health services for vulnerable populations in the South Bronx.

Weesjes Sabella received her PhD from the University of Sussex. Her dissertation, Children of the Red Flag: Growing up in a Communist Family During the Cold War (2012), as well as the majority of her publication record, share the common methodology of understanding culture and identity through oral history.