Ecuador April 18, 2016 © International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Cresent Societies

By Elke Weesjes

Earthquakes are far from equal, and so are the disasters they spawn. That was the case recently when seismic events in Japan and Ecuador provided a textbook case for how the built environment can exacerbate (or not) the impacts of disaster.

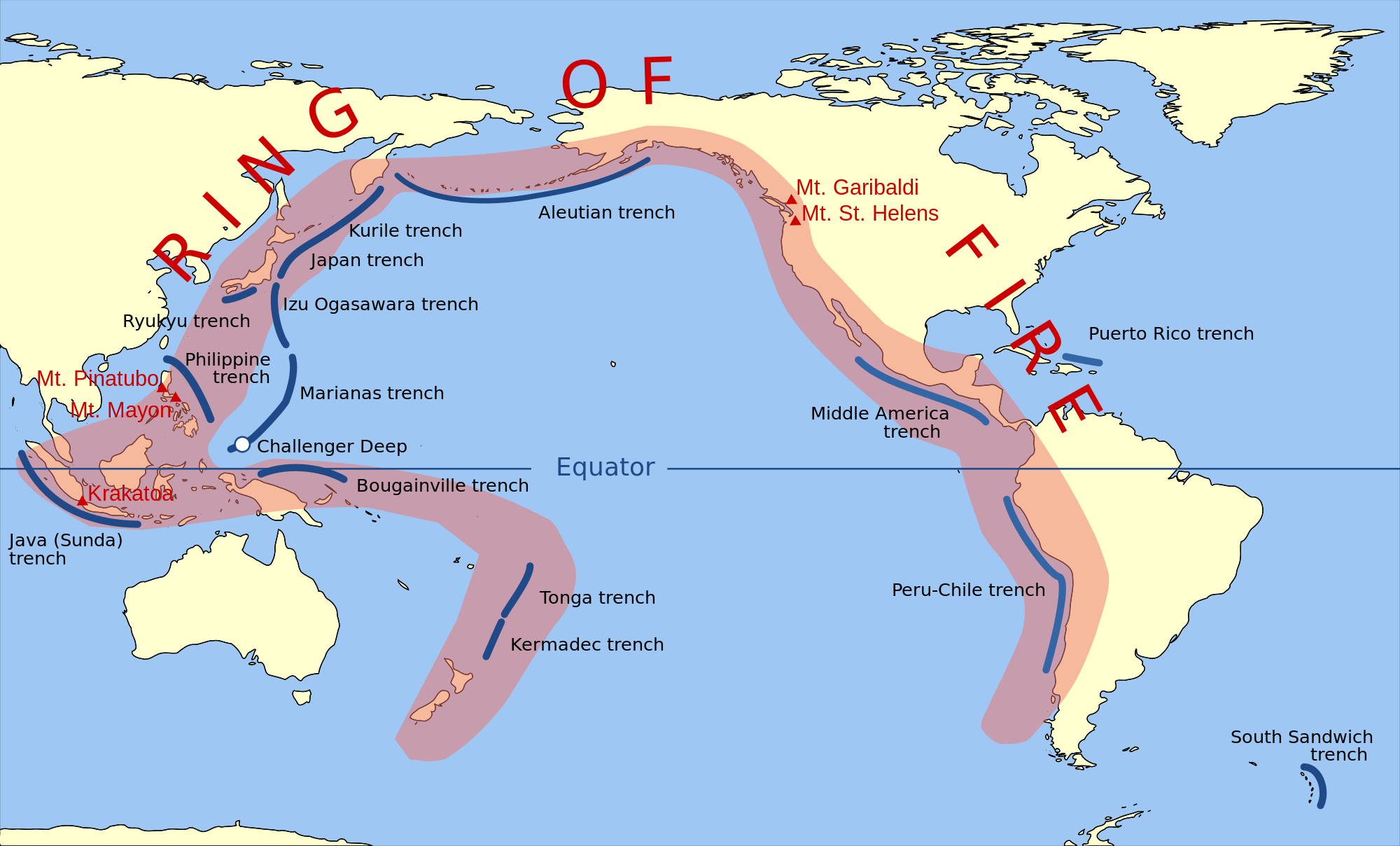

The two countries—both located in the seismically active Ring of Fire zone in the Pacific—were struck by devastating earthquakes last week. Southern Japan was first hit by a 6.2 magnitude temblor on Thursday (now believed to be a foreshock) and then again by a 7.0 magnitude earthquake on Saturday. Hours later, a 7.8 magnitude quake struck Ecuador’s central coast.

According to the latest information, 42 people were killed in Japan, while the death toll in Ecuador is at 413 and expected to rise significantly.

“We have just begun our work,” a rescue worker told the English-language website Cuenca Highlife. “There will be thousands more.”

Aside from timing and their location on opposite ends of the Ring of Fire, the earthquakes don’t have much in common. Still, the death toll has caused experts to make comparisons between Japan’s successful earthquake mitigation efforts on one hand, and Ecuador’s lack of retrofitting on the other.

The earthquake in Japan was actually more powerful than the one in Ecuador, where the 12-mile deep rupture would have created less shaking at the ground surface, according to David Rothery, a professor of planetary geosciences at The Open University in England. Nevertheless, the destruction in Ecuador was much more severe.

“The greater damage to buildings and the probable greater loss of life in Ecuador may reflect poorer adherence to seismic building codes in the construction of buildings and bridges,” Rothery wrote in a post on the Science Media Center website.

Although Ecuador is no stranger to devastating earthquakes—since 1900 there have been seven magnitude 7 or greater quakes within 150 miles of this one, according to the United States Geological Survey—the country’s earthquake prevention and preparedness isn’t as strong as it could be.

This isn’t for a lack of trying. In general, Ecuador has made positive strides in reducing disaster vulnerability and is among the top five Latin American countries to make the most progress toward reducing risk reduction in the past decade, according to the World Bank.

“We have seen an important shift from emergency response to prevention,” Anna Wellenstein, Sector manager for the World Bank Latin America Prevention Unit, said in a report on The World Bank Website.

Ring of Fire © Wikimedia

The horrific images of the death and destruction after Ecuador’s earthquake are an urgent reminder that more needs to be done, though, especially in regards to stricter building codes.

Commercial and industrial buildings in Ecuador generally adhere to stricter construction standards than residential structures, according to a report in the Insurance Journal. The article, which cites catastrophe modeling firm Air Worldwide, also said building code enforcement varies throughout the country and noted that the seismic performance of buildings is highly influenced by local construction practices.

“Building damageability is often exacerbated by poor workmanship, inadequate materials, and a lack of building code enforcement,” according to an Air Worldwide statement quoted in the Insurance Journal.

That was true for Pedernales, a tourist town with a population of 50,000, that was hit hard by the quake. About 80 percent of the homes were damaged or completely destroyed, according to Diego Castellanos, a spokesman for Ecuador’s Red Cross.

“The first technical analyses in these areas show that the buildings haven’t been properly supervised and this creates a problem in these types of events,” Castellanos told the The Wall Street Journal. “There was no time to evacuate because the structures collapsed due to the weakness of material.”

Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa told reporters during a visit to the region that building codes had been improved in 2014. Unfortunately, the majority of structures that collapsed were built before then and hadn’t been retrofitted.

While such devastation coming within hours of a larger, but less deadly event in Japan, it might be easy to come to the conclusion that Ecuador has a thing or two to learn. Unfortunately, the ability to prepare and mitigate quakes is also not created equal.

After the 1995 Kobe earthquake, which killed nearly 6,000 people and injured 26,000, Japan invested billions of dollars into research about how to best protect new structures and retrofit older and more vulnerable structures. The country has since become a world leader in engineering shake-proof buildings.

It took Japan, one of the most highly developed nations in the world, many years and enormous resources to achieve that level of safety. It is unlikely that a developing country such as Ecuador could find the funds to do the same. Still, even while high-tech structures with huge shock absorbers, walls that slide, and Teflon foundation pads might be out of reach, there are low cost, earthquake resistant building technologies available. The new stricter building codes are in place, and Ecuador will have the opportunity to construct safer and sturdier houses.

“The Japan and Ecuador earthquakes show how far we have come, and how far we have to go, regarding seismic safety,” writes Ilan Kelman, co-director of Risk RED. “The comparatively low death tolls show that we can construct buildings to withstand large, shallow tremors. For me, the number of fatalities is still too high, since we know what to do to stop buildings collapsing. The challenge of disasters remains in using the knowledge we have already to save even more lives.”

Elke Weesjes Sabella is former editor of the Natural Hazards Observer. She joined the staff in December 2014 after a brief stint as a correspondent for a United Nations nonprofit. Under her leadership, the Observer was revamped to a more visual format and one that included national and international perspectives on threats facing the world. Weesjes was the editor of the peer-reviewed bimonthly publication United Academics Journal of Social Sciences from 2010 to 2013.

Weesjes Sabella also worked as a research associate for the Center for Disaster and Risk Analysis, formerly located at Colorado State University (although no longer active). In that role, she collected and analyzed data and translated research findings for a broader audience. She played a central role in finalizing the Disaster Preparedness among Childcare Providers in Colorado project, which examines all-hazards preparedness in daycares and in-home childcare across Colorado. She co-authored the report based on the first stage of the project, which was funded by Region VIII of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Weesjes Sabella specializes in cultural memory and neighborhood/community change in times of acute and chronic stress. She has published articles on the impact of drought on farming communities in Kansas, the effects of Superstorm Sandy in Far Rockaway, Queens, urban renewal in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, and health services for vulnerable populations in the South Bronx.

Weesjes Sabella received her PhD from the University of Sussex. Her dissertation, Children of the Red Flag: Growing up in a Communist Family During the Cold War (2012), as well as the majority of her publication record, share the common methodology of understanding culture and identity through oral history.