Women of Gee's Bend Alabama Quilting 2005 © Andrea Natta

Quilting, like other textile arts, is a centuries-old tradition, engaging many different kinds of artists who work on myriad themes, in different contexts and for different reasons. Traditionally a women’s handicraft, this art form of putting salvaged fabric scraps to new use now engages men as well. Although classically made of cotton or wool, some quilts today are constructed from wood or paper. Fabric quilts may be hand-stitched or made by machine—even digitized.1

The purposes and contexts of quilts are as varied as their colors and patterns. Some quilts, known as relief or charity quilts, have been donated for generations to families in need. Others are made specifically for sale or auction, raising funds to support homeless or domestic violence shelters, for instance. Quilters also put their art to use to raise awareness about cancer and other diseases, honor military veterans, or commemorate historical events and traditions. Quilters often memorialize loss. Consider the many AIDS quilts featuring individual faces that traveled around the United States in the 1990s,2 or quilts reflecting on the effects of colonization on indigenous communities.3 Similarly, artists in Chile demonstrated dictatorship through brightly colored patchwork images known as arpilleras, which memorialized los desaparecidos (the disappeared).

Another strand of quilting, one this article explores most deeply, is an artistic and humanistic response to environmental, technological and intentional disasters. These vivid expressions of the social fabric cover and comfort survivors, and also reflect important ideas and emotions when things fall apart. Like other people who speak through song, rap, poetry, murals, graffiti, art exhibits, books and movies, quilters give expression to human loss and renewal (Enarson, 1999, Webb, 2007; Weesjes, 2015). Whatever the context, quilting brings people, especially women, together, building community solidarity and enriching the lives of those who give as much as those who receive. Disaster recovery and resilience are surely supported by these beautiful gestures of solidarity and support, including the many 9/11 quilts that traveled the nation for years and now grace the nation’s capital.4

In 2016, my colleague Naomi Weidner and I launched the Disaster Quilting Project website to help make the beauty and functions of these quilts more widely known.5 Still under development, the website shows quilt photos organized by hazard, and it offers links to numerous publications, videos and other resources about quilting (for disaster folks) and about disasters (for quilters). Visitors can use the blog function to reflect on individual quilts or exchange ideas about art and disaster.

Quilters are tightly networked, which is important in disaster communication and collaboration. They often work with others through geographically-based guilds or networks, and may be connected through social media across many national borders. Their strong community bonds as well as their artistry and commitment to disaster relief volunteerism position them as significant partners in community-based disaster-risk management (UNFPA, 2012; Roach & Westbook, n.d.). Rural women, women of color and older women, many of whom are quilters, bring unique perspectives to hazard and risk management that are not always heard. They might assist disaster planners through their local knowledge of community history, needs and assets, and lend their skills to nontraditional disaster-communication campaigns.

What disaster quilts show us

Virtually every quilt tells a story, so disaster quilts intrinsically help document disaster events and what they mean to people. Some arise from personal experience, while others are community projects, with individual quilters contributing blocks that eventually become one group or “challenge” quilt. For instance, in the spring of 1997, when the flood waters of the Red River finally receded and the mandatory evacuation of their community ended, members of the North Star Quilters Guild in Grand Forks, North Dakota, got to work. Each member contributed a quilt block telling her own story. All blocks were then stitched together in a jointly constructed commemorative quilt. One quilter created a fabric image of a temporary toilet perched on a berm outside her home, so important to mother and child during toilet-training in flood time. Another chose the unusual embroidered “crazy quilt” motif6 to write a few words on her quilt block explaining how she managed her mental illness during the flood.

Guilds in hard-hit regions may well respond artistically with disaster-themed quilts created by individual members, or they may quickly produce and distribute simple quilts, primarily as a gift of warmth and comfort. Small businesswomen serving quilters frequently initiate campaigns of this sort in the immediate aftermath of a tornado or earthquake, especially but not exclusively if it is local.7 After posting an appeal with directions, patterns, and deadlines, they generally try to forward along the stacks of donated quilts that will arrive at their doorstep. They may also post contact information about pre-determined collection points, shelters or volunteers knowledgeable about local needs and capacities.

Some quilters bring an artist’s eye to chaos and destruction, producing award-winning textiles in response to disasters or to hazards such as toxic contaminants or nuclear power. These quilts may be donated, sold or auctioned to raise disaster relief funds, as is often the case when quilters rally after a disaster or to meet other urgent community need. Quilters themselves may receive donated supplies from other quilters out of their region along with messages of support if their working spaces are degraded or destroyed in a disaster. Other quilters use their artistry to express dissenting or alternative ideas, such as quilting about how water degradation and loss affects women and girls or about ecological degradation tied to climate change.8

Disaster quilt campaigns engage quilters in the collective work of remembrance, protest or commentary, speaking through their craft to console those who suffer. Writing from Australia after massive bushfires in 2009, contributors to the 59-block Mudgegonga Community Quilt explained how the colors chosen reflected the local terrain and the earth blackened by fire, explaining: “Two precious lives were lost; seventeen homes destroyed; cattle, sheds, fences, tractors, cars, gardens and plantations all destroyed. From the midst of this devastation, a renewed and strengthened community gathered and supported each other with an outpouring of love, care, kindness and compassion. We were overwhelmed with the generosity of our community and our country. The quilt depicts the individuality of the residents and the cohesiveness of the whole community.”9

Disaster quilting is unifying at a time of crisis, whether quilters work alongside others in their local guild or respond from afar with quilt blocks or quilts made to order for a specific disaster response campaign. Heartfelt thanks may come in return. A hand-written note from a survivor of the EF5 tornado that struck Moore, Oklahoma, in 2013, read: “Thank you for your love and support. The quilts will replace the ones that were lost from our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. They will help us fill the void in our homes and in our hearts.”10

Finally, quilting can be an act of solidarity with lasting effect, such as in the case of the U.S. group “The Quilting Queens,” which emerged after Hurricane Katrina. Its members were all women who volunteered at the Northwest Louisiana Hurricane Relief Center in in Minden, Louisiana, a small rural town to which many residents had evacuated. Experienced quilters there came together with newcomers to the art, helping them learn the basics of quilting in a project which, over time, functioned to “bring people together for a common cause, to raise money, to provide a means for self-expression, to heal their depression, and to reach across a century of racial division in this rural Southern town.”11

The quilt images below exemplify these many themes and the ‘ties that bind’ we know to be so critical in disasters.

Close ups: Disaster quilt gallery

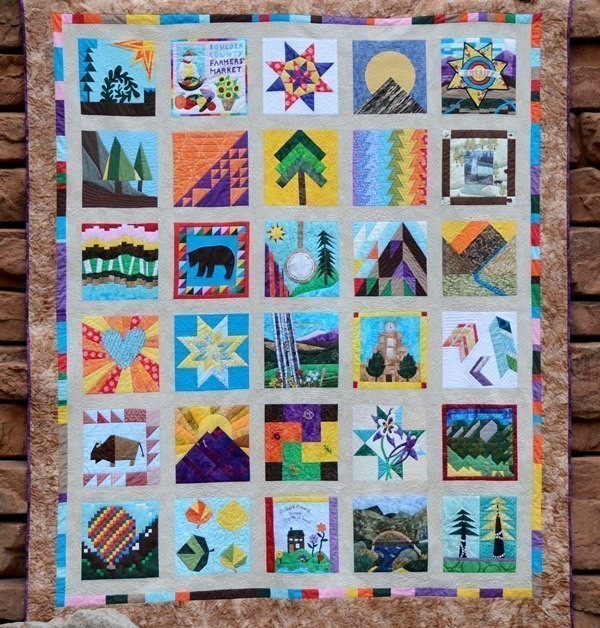

Quilts also memorialize disasters. In Boulder County, Colorado, a commemorative challenge quilt, initiated by county employees rather than by a quilting guild12, was created to mark the 2013 “flood of the century.”12 Quilters were provided instructions and invited to submit blocks for possible inclusion working with the theme “Boulder County: Strong and Beautiful.” The quilt was created from 30 selected blocks donated by quilters in California, Iowa, Minnesota, North Carolina and Tennessee, as well as Colorado. On the first anniversary of the flood the quilt was presented to the public at the county courthouse, and it is still proudly hanging in the courthouse hallway. Viewers can also access an online version and learn more about the flood from numerous points of view by clicking on a single block. A quilter from the state extension office contributed a block featuring four colorful overlapping blocks, intending to: “represent the four program areas of our office: agriculture, 4-H, family and consumer science and horticulture. The intertwining represents how we came together as an office to relocate our office when it flooded, but also how we came together to put together answers to questions the public was asking post flood. They also represent how all county employees came together with other agencies to help those affected by the flood.” Another message on a star-patterned block quilted by Katie Arrington, Boulder County flood-recovery specialist, was more symbolic: “The star is supposed to be a bright star on a bright night, just before sunset.”

Colorado Commemorative Flood Quilt © Lewis Geyer, Longmont Times-McCall 2015

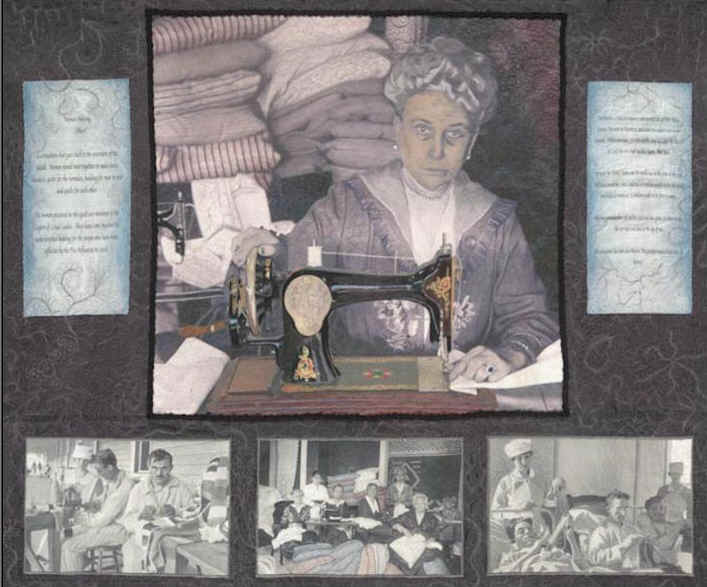

In contrast to this contemporaneous disaster quilt, Santa Fe designer and quilter Jennifer Day tells the historical story of women who stitched for the infirmed during the 1918 U.S. influenza epidemic. Her “thread story” about Women Helping Othersis based on fabric imprinted with a photographic image around which the quilter then creates her own unique “thread story.”13 This is a rare look back through quilting, and a rare textile reflection on pandemics.

Women Helping Others by Jennifer Day. Legion of Loyal Ladies came together to make hospital bedding for those afflicted by the 1918 influenza © Jennifer Day

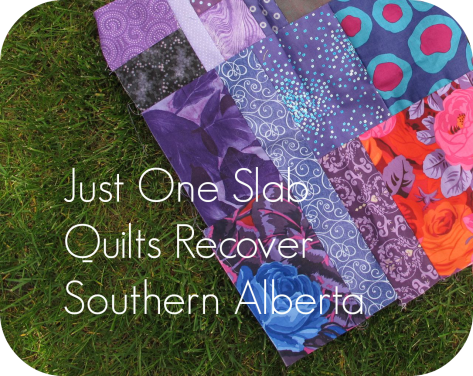

Quilts are often constructed through virtual campaigns to create and distribute urgently needed functional bedding. These disaster-response campaigns arise spontaneously and quickly, one disaster at a time, facilitated by Facebook and other social media. Aiming simply to quickly create large quantities of warm quilts for survivors, individuals frequently contribute to or initiate local, national or even global quilt campaigns. Quilts for Nepal, for example, was a short-lived group launched by a self-described Scottish “unsuspecting librarian by weekday, vigilante heroine seamstress by weekend” after the 2015 earthquake that left so many homeless and bereft.14 In northern Alberta in May of 2016, while fires were uncontained and thousands of residents were still evacuated, a “Quilts for Fort MacMurray” campaign was already well-underway on Facebook that same month.15

Just One Slab for Alberta Flood Relief @ Cheryl Arkison 2013

Quilters, including disaster quilters, readily share ideas and techniques with others. This spring, as floods hit Texas, for example, quilters there followed the lead of a Canadian campaign in which donated fabric “slabs,” rather than elaborate individual quilt blocks, were stitched into whole quilts by volunteers. The woman organizing the “Flood Texas with Love” quilt campaign invited contributors this way: “It doesn't take long to make a slab. And trust me, they add up! Beautiful quilts, comfort of strangers. It is all worth an hour of your time to make and mail a slab.”16

Tornado Quilts for Moore @ Luana Rubin, E-Quilter 2013

Disaster quilting initiatives vary in length. Many quilters participate in faith-based networks that have contributed relief quilts for decades, such as the Mennonite Women USA. Their “Housewarmer Project” provides a quilted wall-hanging for each displaced family moving into a newly built home.”17 Recently, the new network Tewassa arose through the efforts of Americans with strong Japanese ties to help support survivors following Japan’s earthquake, tsunami and nuclear explosion in March 2011. It was specifically conceived as a “long-term volunteer project devoted to Japan Earthquake and Tsunami relief through handmade arts + crafts.” Based in Boston, Massachusetts, where they were able to engage college students from local institutions in their work, Tewassa volunteers regularly visit affected regions to deliver hand-crafted gifts. Every year a quilt is delivered, the first created by children drawing on cloth. It was delivered in the fall of 2011 to elementary school students from the Miyagi Prefecture Okawa school, where 70 of 108 students died when the school was destroyed. In 2015, four years after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, they presented a quilt of solidarity to a group of 60 survivors in Kazo City, a small community that still hosts 500 displaced people. Still searching for information about disaster aid and nuclear contamination, a spokesperson for the survivors stated, “We will live looking ahead.”18

Tewassa Message Quilt delivered to residents in Saitama, Japan @Tewassa 2015

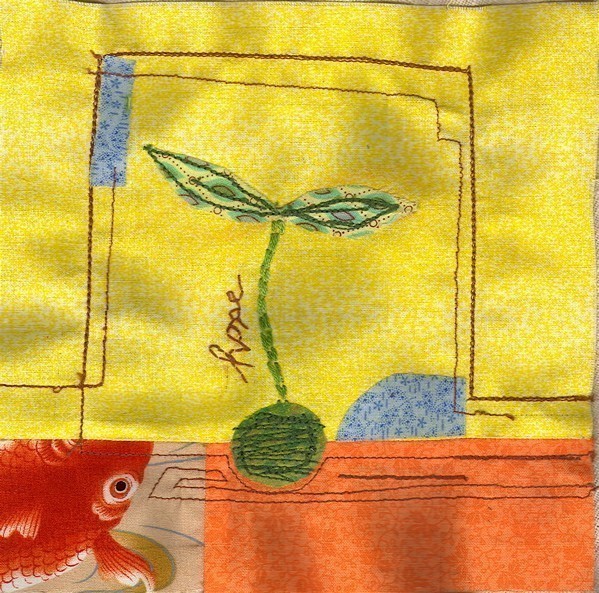

Hope. First block blogger Karen ever made, responding to Japan’s 2005 Miyagi earthquake and tsunami © Karen 2005

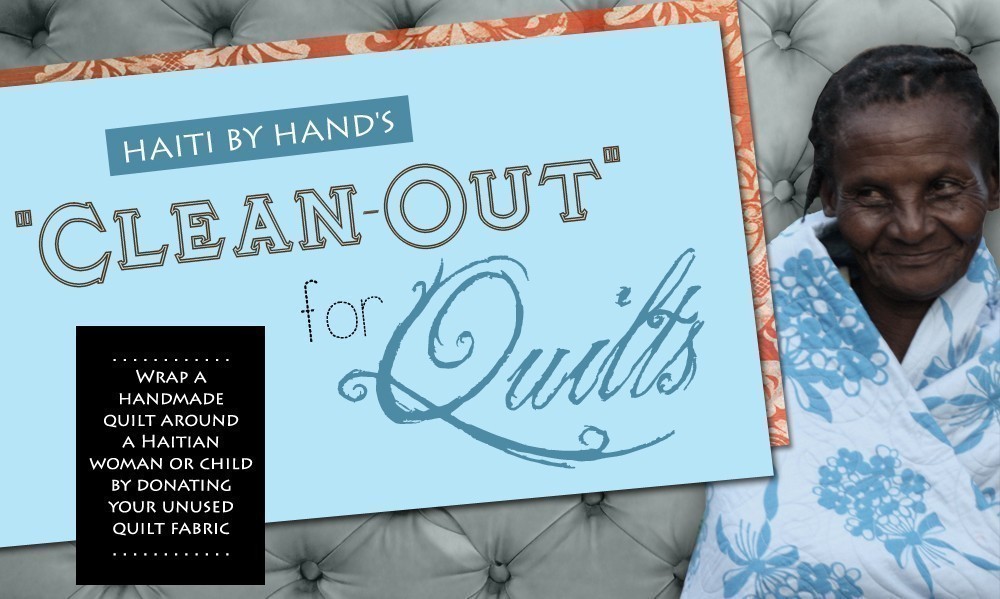

Quilting can also facilitate post-disaster economic recovery. Following Haiti’s 2010 earthquake, a quilting collective called Peace Quilts sought to encourage talented seamstresses by helping them to find a market for their completed quilts. As one of Peace Quilt’s founders emphasized: “We’re volunteers. We pay our own way down to Haiti. All the funds raised from the sale of quilts go back to the quilters. We have a touring exhibit and a catalog we publish ourselves.”19

Haiti By Hand’s Clean-Out for Quilts © Haiti By Hand 2011

Individual losses may also be recognized by disaster quilters. For example, when the 2012 earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand, destroyed one woman’s business, she created and sold a line of screen-printed tea towels with the logo Sure To Rise to earn some money to rebuild. Her neighbor and friend, wanting to acknowledge her strength, pieced these tea towels into a unique quilt as a way of “saying to one family, we acknowledge that things were truly awful for you, and we respect you for how you have carried on.”20

Sure to Rise shown against a wall mural in Christchurch © D. Robertson 2014

Quilter Susan Schrott speaks through quilting as an individual whose art was inspired by disaster volunteer work. Her quilt Shalom Y’All) commemorates a 2006 service trip to Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina, along with teenage volunteers from New York.21 With camera and notebook in hand, she set out to create this remembrance quilt. Schrott writes that her quilt was “inspired by the overwhelmingly hopeful reactions of the Katrina victims themselves.” Asked repeatedly to “Tell our story,” she built the quilt around the tree-of-life image to reflect a spirit of renewal, growth and strength. Now displayed at the United Jewish Appeal office in her hometown of Mount Kisco, New York, she says the quilt is still “helping to keep my promise to tell the story to as many people as possible.”

Shalom Y’All © Susan Schrott 2006

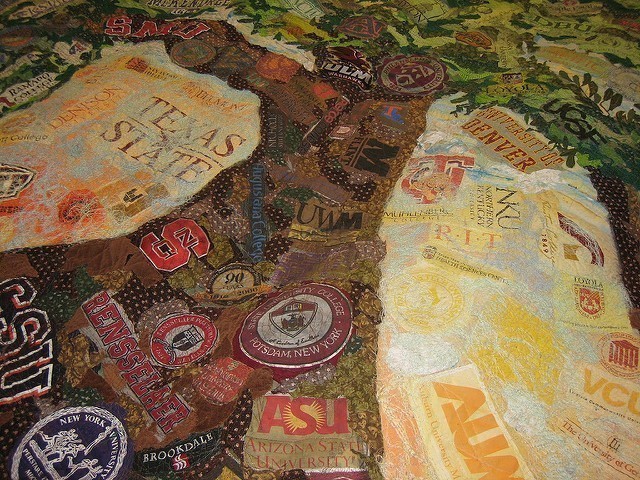

Live Oak by Gina Phillips, 2007. Tulane University displays this quilt in the faculty/staff dining room to recognize the many colleges and schools that hosted students after Hurricane Katrina © A. Levine

In the same spirit, Louisiana members of the Peaceful Quilters guild were commissioned to create a quilt about the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Five artists worked together to quilt Beyond the Horizon in order to make “a statement about the oil spill—don’t let it happen again.” Aiming for maximum exposure, they first displayed the quilt on Earth Day and then placed it on permanent display at the State Archives Building in Baton Rouge.22 Also addressing environmental concerns, Barbara Eisenstein’s quilt Wind to Enlighten is part of the Solar Sisters series launched by Quilters for Change, an international network depicting the gender dimensions of armed conflict, pandemics and natural disasters. Her wind power quilt highlights renewable energy and appeared with others in the high-profile Solar Sisters exhibit opening at UN headquarters in New York City.23

Beyond the Horizon by Peaceful Quilters Judy Holley, Sherry Herringshaw, Nina Delaune, Melanie West and Michael Young © T. Holley 2014

Wind to Enlighten by Barbara Eisenstein © C. Abramson 2015

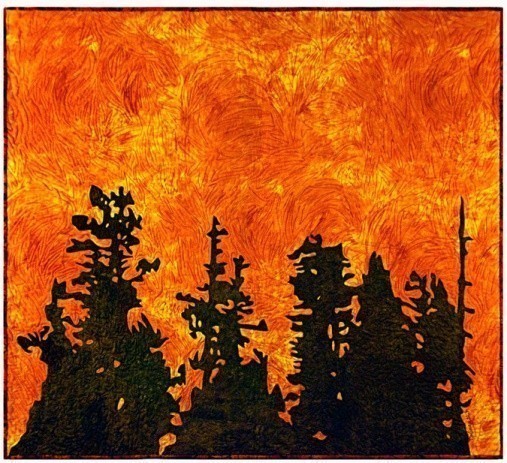

Yet another genre of artistic disaster quilting allows quilts to represent disasters, sometimes showing symbolic loss or unexpected beauty. Quilters often speak through their art about how forest fires, extreme storms or earthquakes reshape places and people, sometimes through commonly selected themes. In California, when the African American Quilt Guild of Oakland chose the theme “sense of place” for its members to consider, Guild member Marion Coleman created a quilt depicting her “sense of pride and possession about our place,” under assault from gentrification to wildfire.24 This was a story she knew well, working as a social worker when more than 3,000 residences were destroyed by wildfires sweeping through the Oakland-Berkeley hills in 1991, killing 25 people.

Firestorm by Marion Coleman © E. Murphy 2015

Using the ties that bind: Next steps

A world of opportunity exists for building on the strengths and common purposes of practitioners and quilters.25 Imagine if quilting guilds were asked to help design public education materials. What might this look like? Could disaster quilters and other fabric artists help spread the word about preparedness to those not inclined to download documents or visit government websites? What if quilters who have lived through a disaster shared disaster blocks about their experiences in community meetings with residents in similar communities also at risk? Could traveling disaster quilt exhibits, or virtual exhibits circulated by lead quilting organizations, liven up the conversation during Emergency Preparedness or Disaster Risk Reduction month? What groups in your community might enjoy a prevention or recovery presentation built around disaster quilts with photographs, stories and maybe a borrowed quilt or two? How about bringing quilters into emergency planning committees for a fresh take on risk communication or asking them to help children work with paper or fabric to quilt their own stories after a disaster?

How do you think quilters and practitioners could collaborate? Share your ideas on the Disaster Quilting Project website.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to all quilters for sharing their work and to Naomi Weidner for her help building the Disaster Quilting Project.

References

Enarson, E. 2000. "We will make meaning out of this:’ Women’s cultural responses to the Red River Valley flood" International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 8 (3), 39-62. Retrieved from http://www.ijmed.org/articles/169/ (accessed June 1, 2016).

Weesjes, E. ,. (Ed.) 2015. Art and disaster, [Special issue] Natural Hazards Observer, 39 (6). Retrieved from https://hazards.colorado.edu/uploads/observer/2015/jul15_observerweb.pdf (accessed on May 23, 2016).

Roach, S. and Westbrook, L. n.d.) Quilts as women's documents: The Louisiana Quilt Documentation Project. Retrieved from http://www.louisianafolklife.org/LT/Articles_Essays/main_Quilts_women_doc.html (accessed May 31, 2016).

Webb, G. (2007). "The popular culture of disaster: exploring a new dimension of disaster research" In Rodriguez, H., Quarantelli, E.L.,Dynes, R. (eds.). Handbook of Disaster Research (pp. 430-440). NY: Springer.

UNFPA. 2012. Women are the fabric, quilts reflect their strength. Retrieved from http://www.unfpa.org/news/women-are-fabric-quilts-reflect-their-strength (accessed June 1, 2016).

-

Among others, Richard Voigt prints out canvas quilt block sections of computerized quilt images based on scanned images, including his digital Katrina quilt Eye of the Hurricane, “inspired by a TV screen shot of Hurricane Katrina. While it ravaged a section of our country, the symbolic weave kept was intended to show our nation's resilience to disaster.” Visit his site here: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/533958099544670078/(accessed June 2, 2016). ↩

-

The AIDS Memorial Quilt Project is one example: http://www.aidsquilt.org/about/the-aids-memorial-quilt (accessed June 1, 2016). ↩

-

"The Alice Williams Quilt "We are all crying—a quilt for 1992" illustrates this. Working from the Curved Lake First Nation Reservation in Ontario, Canada, Williams depicts the “destruction, exploitation, hate and carelessness” brought by Christopher Columbus centuries ago and still affecting everyday life. Read more here: http://disasterquiltingproject.com/essential_grid/we-are-all-crying-a-quilt-for-1992/ (accessed June 1, 2016) Though debate continues, U.S. quilters may have embedded codes in individual block patterns to help guide enslaved African Americans to relative safety along the Underground Railway. For a positive account, see the classic Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad by J. Tobin and R. Dobard, 2000, or one of many YouTube videos on the question of coded escape routes embedded in quilt blocks. ↩

-

See, among others, the 9/11 Memorial Quilt Project: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/09/0909_030910_911quilt.html; America’s 9/11 Memorial Quilts Project: https://www.911memorial.org/tribute/america-911-memorial-quilts-project; and the innovative 9/11 Bead Quilt: http://www.beadcave.com/beadquilt/index.html (accessed June 2, 2016). ↩

-

Visit the website here: www.disasterquiltingproject.com. ↩

-

Explained here: http://www.craftsy.com/blog/2014/08/crazy-quilting-embroidery/ (accessed June 13, 2016) ↩

-

The on-line quilting store E-Quilter, for example, frequently partners with Mission of Love or other relief groups to collect and deliver relief quilts: http://www.equilter.com/ (accessed June 13, 2016) ↩

-

For one example: http://quiltforchange.org/2016/05/water-line-phyllis-stephens/ (accessed June 1, 2016) ↩

-

For more on the Mudgegonga Quilt Project: https://mudgegonga.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/mudgegona-quilt-book2.pdf (accessed June 13, 2016) ↩

-

E-Quilter tornado quilts: https://www.flickr.com/photos/luanarubin/9278193193/in/album-72157634238654411/ (accessed June 1, 2016). ↩

-

Sue Roach, The Quilting Queens: Responding to Katrina: www.quiltindex.org/essay.php?kid=3-98-26 (accessed May 27, 2016). ↩

-

Longmont Times-Call, Sept. 7, 2014: http://www.timescall.com/longmont-local-news/ci_26483312/flood-quilt-commemorates-anniversary-honors-boulder-county-survivors (accessed May 27, 2016). ↩ ↩

-

To see more of her work, visit Jennifer Day’s gallery: http://www.jdaydesign.com/ (accessed June 2, 2016). ↩

-

Karen McAulay, Quilts for Nepal: http://www.pechakucha.org/presentations/quilts-for-nepal (accessed May 27, 2016). ↩

-

https://www.facebook.com/Quilts-For-Fort-McMurray-1732100640402657/ (accessed June 2, 2016). ↩

-

http://www.cherylarkison.com/naptimequilter/2015/06/flood-texas-with-love.html (accessed June 2, 2016). ↩

-

The Housewarmer Project: https://mennonitewomenusa.org/housewarmer/ (accessed May 27, 2016). ↩

-

Tewassa presentation ceremony: http://www.tewassa.org/jp/news/1416 (accessed May 27, 2016). ↩

-

Lisa Paravaseni, Handmade quilts a lifeline for Haiti. Repeating Islands, 2011: https://repeatingislands.com/2011/08/27/handmade-quilts-a-lifeline-for-haiti/ (accessed May 27, 2016) Disaster quilting is not without its critics. For a dissenting view, see “Quilts for Haiti? I don’t think so” by Kathleen Loomis: http://artwithaneedle.blogspot.com/2010/01/quilts-for-haiti-i-dont-think-so.html (accessed June 1, 2016) ↩

-

Deb Robertson: http://deb-robertson.blogspot.com/search?q=tea+towels(accessed May 27, 2016). ↩

-

For a complete account of this quilt by Susan Schrott: http://katrina.jwa.org/content/vault/Shalom%20Yall%20Quilt%20and%20UJA%20Trip%20Description_f9069fd57b.pdf (accessed June 2, 2016). ↩

-

Laura Marcus Green, “Stitching Community: Fiber Arts and Service” forthcoming for Folklife in Louisiana : http://www.louisianafolklife.org/LT/Articles_Essays/brfiber1.html (accessed June 1, 2016). ↩

-

Learn more about environmental hazard quilts from Quilt for Change here: http://quiltforchange.org/light-hope-opportunity-empowering-women-through-clean-energy/solar-sister/ (accessed June 1, 2016) ↩

-

Patricia Brown, Feb 2, 2016, Quilts With a Sense of Place, Stitched in Oakland: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/03/arts/design/quilts-with-a-sense-of-place-stitched-in-oakland.html (accessed May 27, 2016) ↩

-

The Disaster Quilting Project website includes Bridging Gaps: Ten Steps for Engaging Quilters and Practitioners: http://disasterquiltingproject.com/contact/bridging-gaps-ten-steps-toward-collaboration/ (accessed June 1, 2016) ↩

Elaine Enarsson is an independent educator, public speaker, international consultant and qualitative researcher with a focus on community-based disaster prevention and gender equality in disaster contexts.

Through academic field studies and consulting, she has explored gender violence, gender-responsive recovery, women’s work and political mobilization in disasters and related topics in the United States, Canada, Australia, India and Indonesia.

In addition to academic publications and training and practice guides, Enarsson has co-edited three international readers on gender and disaster and published the U.S.-focused book Women Confronting Natural Disaster: From Vulnerability to Resilience. Her latest work is the co-edited volume Men, Masculinities and Disaster. These activities inform her interest in climate change, on-line teaching in disaster and emergency management graduate programs and her community work.

A co-founder of the Gender and Disaster Network and founder of the U.S. Gender and Disaster Resilience Alliance, Enarsson recently initiated the Disaster Quilting Project. She is happily based in Hygiene, Colorado.