By Hanna Ruszczyk

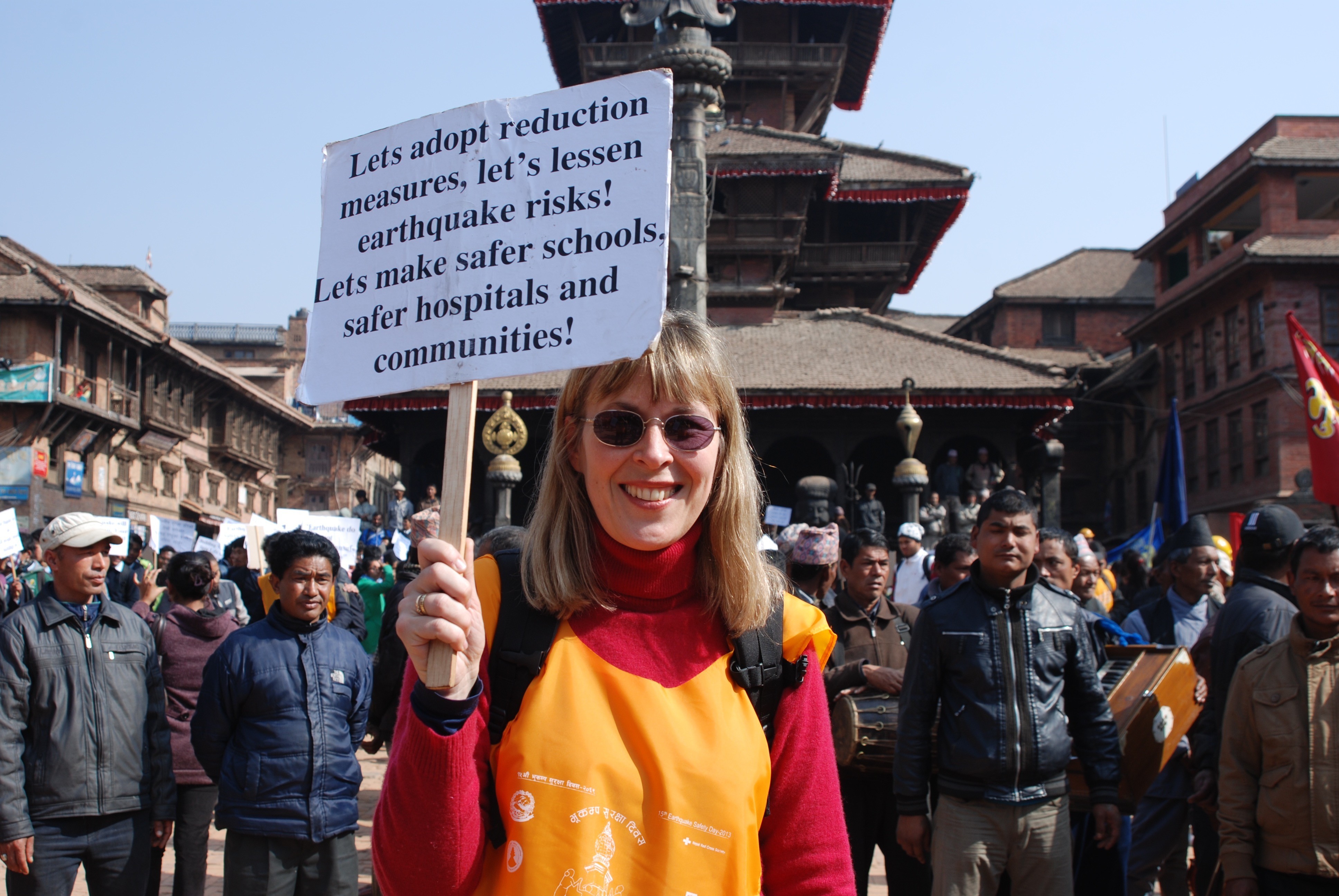

Ruszczyk on Bhaktapur Durbar Square in Kathmandu Valley before the Gorkha Earthquake © Hanna Ruszczyk

There is an ancient Indian fable that tells the story of six blind men who had often heard about elephants, but, being blind, had never actually seen one. Curious about the creature, the six blind men visit the Rajah’s palace where they touch an elephant with their hands, hoping to envision what the animal might look like. But because the animal is so big they all touch different body parts and they consequently have very different impressions of what an elephant looks like. When they discuss their findings with the Rajah, they are all adamant their view is correct. The Rajah, a very wise man, explains that they were all correct, albeit partially and tells the men that they can only get an accurate idea of what an elephant looks like when they step back and incorporate different views.

This fable, which teaches us—among other things—about the importance of being open-minded, sprang to mind when I was reading and watching news reports about the earthquake in Nepal in the days, weeks, and months after the earth’s upheaval. These reports seemed to focus primarily on the dire circumstances in the Kathmandu Valley and Mount Everest, on death and destruction, on bureaucratic red tape delaying disaster aid, as well as on uncooperative and underprepared officials. The international news reports were not necessarily wrong, however. They seemed limited in scope and did not match my personal experiences in Bharatpur, Nepal’s fifth largest city located about 38 miles south of the earthquake’s epicenter in Gorkha. It felt as if I were reading about the elephant’s ear, while I had touched its tail.

In this article I’d like to provide an additional or different viewpoint of the earthquake and its immediate aftermath and briefly discuss the current situation in Nepal. Rather than discussing death, destruction and national incompetence to respond adequately, I want to highlight local disaster preparedness, resilience, and the impact of ongoing initiatives that empowered people to respond quickly during the earthquake and its aftershock sequence. Five months after this catastrophe, we can begin to reflect on the effectiveness of national and international relief efforts and earthquake-awareness programs.

A terrifying experience

On Saturday, April 25, the day of the earthquake, I was in Bharatpur, conducting fieldwork for my ongoing PhD project. My research focuses on the concept of resilience and examines how people in two very different parts of the city understand their sources of resilience. Ultimately, I want to understand if and how community resilience can be enhanced in a changing urban landscape.

Bharatpur is located in the Chitwan district in the Tarai, a belt of marshy grasslands and forests south of the foothill of the Himalayas. In the past 20 years, the city has seen migrants arrive from many different parts of the country. Bharatpur reflects many characteristics associated with urbanizing Nepal. It is a dynamic and heterogeneous city; at its core it harbors long-time residents, but it also teems with new affluent migrants who built their own homes, migrants who are escaping conflict, economic migrants from Bihar, India, as well as new residents from nearby villages that are being amalgamated into the municipality. All of these residents have very different connections to the government, to each other and to their urban physical environment.

Bharatpur is in the process of implementing the national building code and has made provisions for earthquake-resistant construction with the support of the National Society for Earthquake Technology (NSET) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). This, together with the city’s rapid urbanization made Bharatpur an excellent field site for my research.

Post-quake damage in Chautara in Sindhupalchok District district, Nepal. © IOM 2015

I had arrived in Nepal in the beginning of April. This was my second trip to Bharatpur and my fifth to Nepal, and I expected to stay until the end of May. The massive 7.8-magnitude earthquake cut my visit short; I stayed until I was able to leave the country via India a week after the disaster struck. I kept a daily journal to document the earthquake, its aftermath, and my departure through India. The following is an excerpt from my journal describing the day of the earthquake:

“The earthquake started at 11:56 a.m. on the day of rest (Saturday), therefore there were few vehicles traveling, the shops were still closed and few people were out in Bharatpur. My research assistant and I were walking on New Road in the industrial area of town where the India bound trucks get serviced, where buses are made etc. It is a wide unpaved road near the river. I heard thunder. Metal was shaking on the commercial building to my left… People were looking at the sky. I asked R. what he thought was going on. He said: ‘earthquake’…I felt faint and not stable on the ground. There was a yellow haze and it appeared as if waves were coming from the ground and the ground was shaking horizontally. It lasted around a minute-and-a-half. I swayed but did not fall.”

According to projections (USGS PAGER) for Bharatpur, an earthquake could result in as many as 60,000 (30 percent of city’s population) fatalities. There were, however, no deaths. The city’s infrastructure was intact and only a few buildings were damaged. It is unclear why Bharatpur was spared devastation. In the first 72 hours, we experienced 68 aftershocks. It was, quite simply, terrifying. The 6.7-magnitude aftershock on Sunday, April 26, was especially grim and felt almost as powerful as the Saturday earthquake.

The Gorkha Earthquake—felt in Nepal, India, China, and Bangladesh—and the aftershocks that followed killed more than 9,000 people and injured another 23,000. Nepal, which incurred 8,857 deaths and 22,304 injuries (OCHA 2015), bore the brunt of the earthquake— the worst natural hazards to strike the country since the 1934 Nepal-Bihar Earthquake.

Earthquake awareness programs

In the Chitwan district, many of the earthquake-awareness programs were initiated by the Nepali government, the National Society for Earthquake Technology, the Nepal Red Cross, and other organizations. Those programs were in place before the Gorhka Earthquake struck the region, and they have been effective; a cross section of Bharatpur’s society was well informed and knew how to respond during the earthquake. People were taught to “duck, cover and hold,” and they knew to calmly walk outside and gather in open spaces. Some people had planned evacuation routes.

After the earthquake I spent much of the following days walking through the streets of Bharatpur, asking residents where they were at the time of the earthquake and how they responded during the tremors. From these impromptu interviews it became clear that people had learned from the media what actions to take in case of an earthquake—particularly from the radio and the government TV channel—as well as from their children (who had learned basic disaster preparedness at school). The notable exception was those individuals who lived in the slums of the city. They explained to my research assistant and I that they did not know the tremor was a full-on earthquake. Even once they realized what was actually happening they still didn’t know how to respond to the earthquake. Subsequently, we explained to these people what to expect in the ensuing days, and we shared possible coping strategies to deal with the anticipated aftershocks.

My overall impression was that people were calm yet scared. The situation in Kathmandu, as we learned through countless news reports in the international media, was very different; parts of the city were devastated, including the city’s heritage sites, people were buried under rubble, and the situation was chaotic and confusing.

Students practice earthquake drill. Jana Bikash Secondary School, Matatirtha, is in the process of being redeveloped to make the school more earthquake proof. As part of this process children are taught how to take shelter beneath their desks in case of an earthquake. Kathmandu, Nepal. © Jim Holmes for AusAID

Students practice earthquake drill. Jana Bikash Secondary School, Matatirtha, is in the process of being redeveloped to make the school more earthquake proof. As part of this process children are taught how to take shelter beneath their desks in case of an earthquake. Kathmandu, Nepal. Photo by Jim Holmes for AusAID.

Key factors supporting response and relief efforts

It might be hard to imagine, but the impact of the earthquake in Nepal could have been much worse. In the initial aftermath, three factors supported the relief efforts: Firstly, the telecommunication systems did not collapse and people were able to mobilize social capital and humanitarian assistance. The mobile phone system was overloaded but did not fail (phone calls were limited to three minutes for the first days). Overall, people were able to connect with support systems outside of the disaster-stricken area. Internet functioned intermittently, but sufficiently to access information. Social media, such as Facebook, Whatsapp, and to a lesser extent Twitter, were used by Nepali people not only to contact loved ones but also to mobilize resources and share information about the evolving situation in the Kathmandu Valley and beyond. Prime Minister Sushil Koirala of Nepal, who was in Thailand on the day of the earthquake, reportedly found out about the catastrophic disaster that had hit his country, through a Tweet by Indian prime minister Narendra Modi.

Secondly, critical physical infrastructure did not collapse. The Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu was not damaged and international relief was able to reach much of the disaster-stricken area. The road network surrounding the Kathmandu Valley wasn’t damaged either and facilitated the departure of hundreds of thousands of people from the Valley in the days following the earthquake, thus easing the demand on resources in the Valley. And finally, national collective action was mobilized. By day three, informally and through Nepali organizations, Nepali people began to mobilize resources; organize fundraising events; and gather food, clothing, and shelter to be sent to the devastated hill communities. The international media did not highlight these critical local first response efforts. Instead, they largely focused on international aid and bureaucratic bottlenecks.

Five months later

Among disaster risk-reduction professionals, Nepal was immediately compared with Haiti. In Haiti, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake that hit on January 12, 2010, killed approximately 220,000 people, displaced 1.5 million, and destroyed or damaged 300,000 buildings. The death toll from the Nepal disaster is considerably lower, yet a greater number—eight million people—have been badly affected. Over 600,000 houses were destroyed and an additional 285,000 were damaged (OCHA 2015).

The international aid community has learned valuable lessons from the Haiti experience and other events since 2010, including the need for aid agencies to unite in their efforts and work together with the national government, rather than skirting around it; the recognition that the urban areas struggle with very different problems than rural areas; the need to consider long-term economic development alongside humanitarian issues; and the inclusion of those affected in key decisions over how aid money is spent. As such, many mistakes made in Haiti were not repeated in Nepal.

The Haitian diaspora has contributed more than $10 billion to the post-earthquake recovery since 2010 (Multilateral Investment Fund, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014 and Raymond 2015). The Nepali diaspora has been, and continues to be, equally active, not only by sending remittances but also by organizing fundraisers in the United States, in the United Kingdom and other countries, and by providing relief through non-governmental channels. Besides the efforts of the Nepali diaspora and the international aid community, recovery initiatives by the Nepalese must be noted. Specifically, Nepali youths have mobilized and are volunteering their time and other resources to help rebuild their country.

Nepalese people collectively demonstrated tremendous solidarity and support for each other and individuals proved themselves to be extremely resilient and effective in mitigating disaster

Although media reports didn’t necessarily reflect this reality, Nepalese people collectively demonstrated tremendous solidarity and support for each other and individuals proved themselves to be extremely resilient and effective in mitigating disaster.

Lessons learned

Five months have passed since the Gorkha earthquake. Now the focus is not only on providing humanitarian assistance to hundreds of thousands of people who are still in need, but also on recovering form the disaster and understanding what happened and why. Overall, there is much to be learned in the following months and years about the earthquake and its long-term impact on Nepal and the region.

Just as the blind men in the Indian fable, my personal perspective is also partial, but I hope it nevertheless offers some useful insight and a more nuanced image of the earthquake in Nepal and the Nepali response to this tragedy.

After a disaster of such magnitude, the task of reconstruction is never easy. Full recovery takes time; after the photographers, film crews, and aid agencies have moved on, the region will continue to recover. But when we look at Bharatpur, maybe the future for Nepal is more hopeful than we think and perhaps the city will serve as a beacon of hope, or even a yardstick.

Hanna Ruszczyk will return to Bharatpur in late September to continue her fieldwork. She is looking forward to learn how people integrate the earthquake experience into their lives and the effects of this tragedy on the future of Nepal. She intends to contribute another article about the situation in Nepal early next year. You can contact her via email h.a.ruszczyk@durham.ac.uk.

References

Prospery Raymond, 2015. “Building a new Nepal: why the world must heed the lessons of Haiti, The Guardian (Wednesday 6 May 2015) http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/may/06/earthquake-building-a-new-nepal-why-the-world-must-heed-the-lessons-of-haiti (accessed on September 27, 2015).

Multilateral Investment Fund, Remittances to Latin America and the Carribean, 2010, New York/Washington.

Multilateral Investment Fund, Remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean 2011, New York/Washington.

Multilateral Investment Fund, Remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean 2012, New York/Washington

Multilateral Investment Fund, Remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean in 2013, New York/Washington.

Multilateral Investment Fund, Remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean 2014, New York/Washington.

OCHA. 2015. Nepal Earthquake: Humanitarian Snapshot August 10, 2015 http://reliefweb.int/report/nepal/nepal-earthquake-humanitarian-snapshot-10-august-2015 (accessed August 14, 2015).

USGS PAGER (Prompt Assessment of Global Earthquakes for Response) http://earthquake.usgs.gov/research/pager/.

Hanna wrote daily summaries of her earthquake experience and her eventual departure via India. They can be found at: http://www.dogweb.dur.ac.uk/GeoPaD/nepal-earthquake-day-1/ & http://www.dogweb.dur.ac.uk/GeoPaD/returning-home-from-nepal-by-hanna-ruszczyk/