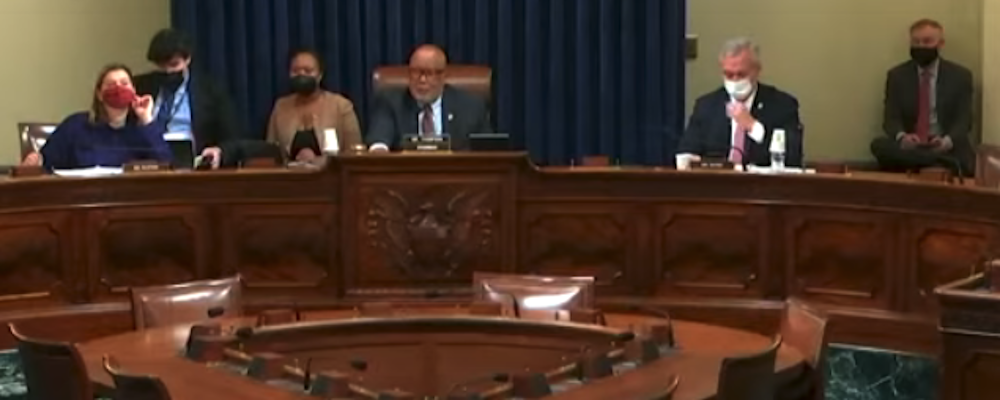

Subcommittee Chairman Rep. Bennie Thompson calls the hearing on ensuring equity in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery to order.

Subcommittee Chairman Rep. Bennie Thompson calls the hearing on ensuring equity in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery to order.

Disaster researchers and professionals have long realized that certain populations bear disproportionate disaster impacts and are less able to access resources to prepare for and recover from extreme events. Recently, lawmakers had an opportunity to hear more about what contributes to this cycle and how federal agencies might begin to address inequities in U.S. disaster management.

Four disaster experts, including Natural Hazards Center Director Lori Peek, testified in front of the U.S. House Subcommittee on Homeland Security about known biases in disaster-related programs, the work being done to address them, and future directions to promote equity.

The experts—which also included Chauncia Willis of the Institute for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Management, Christopher Currie of the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), and James Joseph of Tidal Basin—covered a range of issues during the two-and-half-hour hearing, but several main themes stood out.

Disproportionate Impacts Are Real. Witness and congressional statements pointed again and again to the fact that race, poverty, and other social vulnerabilities often leave individuals and whole communities at a disadvantage in disasters—and that many of the drivers of those disadvantages are built into our U.S. disaster management systems.

Peek presented evidence that showed that current federal programs are not only underserving many populations, but that in some cases they can actually deepen preexisting inequalities. Willis spoke about biases in the Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act that allow politics and bureaucratic processes to stand in the way of providing timely disaster assistance to low-income households and communities of color.

Hearing participants also noted that built-in barriers to receiving aid, especially those that tie property values to assistance disbursements, need to change. Currie’s testimony summarized forthcoming GAO findings on “access barriers and disparate outcomes” in the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Individual Assistance Program and the National Flood Insurance Program, as well as in programs administrated by the Small Business Administration and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Joseph, a former FEMA Region V administrator, submitted testimony that outlined numerous obstacles to program participation, including cost-match considerations, complicated applications for aid, and a lack of equity awareness at the state and local level.

We Still Need More Data. Although federal agencies are working to incorporate equity throughout programs and practices, it was clear from the expert testimonies that there hasn’t been enough agency-level data collected and publicly shared to adequately assess when barriers to access and disparities exist. For instance, Currie stated that, in the GAO’s examination of major disaster programs within FEMA, SBA, and HUD, none of the organizations had demographic information that would help outline disparate outcomes or the impacts on vulnerable communities.

“You can’t fix what you can’t identify or measure,” he said. “Getting the right information and using it effectively will be a critical first step in this to ensuring more equitable outcomes for all disaster survivors.”

Currie went on to say that at least some of these measures have been purposefully left out of studies on how programs affect racial issues because statutes have been interpreted to mean that such data should not be collected.

The missing data has created issues in distributing assistance and determining who needs it the most, however. All of the witnesses pointed out that definitions of vulnerability and equity need to be adjusted so that aid can be tailored to communities and to specific population groups, rather than distributed in a one-size-fits-all manner. Before that can happen, though, agencies and their research partners need the information to understand where funding is uneven.

The Road Ahead is Long. Currently, agencies have begun comprehensive investigations into how to advance equity in response to a recent presidential declaration requiring them to do so.

Even with such a directive in place, however, it is likely to be quite some time before the deeply embedded systemic inequities can be addressed across the federal government. Along with data needs, witnesses cited the need for more equity and inclusion training, more cultural competency among disaster professionals, and a workforce that is representative of the communities that they serve. Policies, processes, and doctrines will also need be revised with equity in mind to achieve just outcomes. Finally, the financial investment to support these changes will be key.

Peek stated that while there is much work to be done, some of the steps now being taken by federal agencies could lead to an entirely new path for those who have historically been denied or overlooked in disaster planning, response, and recovery.

“We know that federal aid doesn’t always reach those most in need,” she said. “This vital process could lead to a fundamental reimagining of disaster aid whereby the vulnerable people who are hit first and worst in disasters are prioritized.”

Jolie Breeden is the lead editor and science communicator for Natural Hazards Center publications. She writes and edits for Research Counts; the Quick Response, Mitigation Matters, Public Health, and Weather Ready Research Award report series; as well as for special projects and publications. Breeden graduated summa cum laude from the University of Colorado Boulder with a bachelor’s degree in journalism.