By Magdalena Schwarz & Elke Weesjes 1

Images: Refugees on Lesvos © Maaike

Last September, after the images of a drowned Syrian toddler named Alan Kurdi made global headlines, it seemed that the humanity of refugees was finally recognized, especially in Europe and the United States. The devastating photograph of Alan, his lifeless body on a beach in Turkey, incited public shock, sympathy and outrage.

Unfortunately, this widespread compassion was short lived. The Paris attacks in November set off a new round of fear-mongering based on false claims that one of the terrorists had a Syrian passport. Anti-refugee and dehumanizing rhetoric came back with a vengeance, both inside and beyond Europe.

Today, refugees have again been reduced to nameless and faceless numbers. When discussing the crisis, politicians, journalists, and experts tend to use pejorative words that reduce the struggle of a large number of individuals to a compressed and oversimplified event: “influx,” “occupation,” “flow,” or even “horde” or “swarm.” These words can make it easy to forget that refugees are not a single parasitic organism vexing Europe, but rather individual human beings trying to escape violence, persecution, as well as economic, political and social instability of war-torn countries.

Although we are constantly given information about the “refugee crisis,” we actually know very little about the refugees themselves who are in crisis—the challenges they face along the way, in transit camps, and even once permanently or temporarily settled in a host country.

A counter-narrative is sorely needed. With this intention, we spoke to 24 refugees and grassroots volunteers to gather informal and anecdotal knowledge.2

This evidence, combined with official primary sources (such as UNHCR statistics) newspaper articles, and other secondary sources, forms the basis of this article, which will correct crisis representations often seen in the media. We also want to highlight how refugees can be an asset to countries, not a burden.

On the move

In 2015 an astonishing 1,000,575 refugees arrived on European shores by boat. These refugees—men, women, and children—faced many dangers on their way to a safer destination. They arrived on old and overloaded inflatable boats, often driven by fellow refugees who lacked boating experience.3

Even in the depths of winter, desperate refugees continued to make this dangerous journey. The human toll was enormous. According to UNHCR statistics, 3,735 people perished at sea in 2015.

While photographs of refugees in overcrowded rubber dinghies have become ubiquitous in coverage of the refugee crisis, we shouldn’t forget that not everyone arrived via sea; in 2015, 34,000 refugees traveled through the Balkans and Central Europe to the European Union. They too, were exposed to danger, brutality, bad weather conditions and many other obstacles along the way.

During her missions in Central Europe and the Balkans, Aude, a volunteer with Migration Aid4 witnessed brutality against refugees firsthand.

“[At the train station of Tovarnik on the Croatian-Serbian border], a large group of a few thousand people, mostly Syrians, Iraqis and Afghanis was waiting for a train to take them to Hungary. The train came and a wave of people rushed into the train to get a chance to move on. People were crushed, babies handed out of the windows. Croatian police attempted to contain overcrowding but was not prepared to face such circumstances. Some started to get violent and beat up some of the people at the train cars’ doors. The train did not move the whole night. After a while these people in overcrowded rail cars were in poor shape. Some women fainted and were taken out of the train at the crying sound of their family members. I spent most of the night distributing water and food through the windows and ensuring most got fed, especially the children” (Aude 2015).

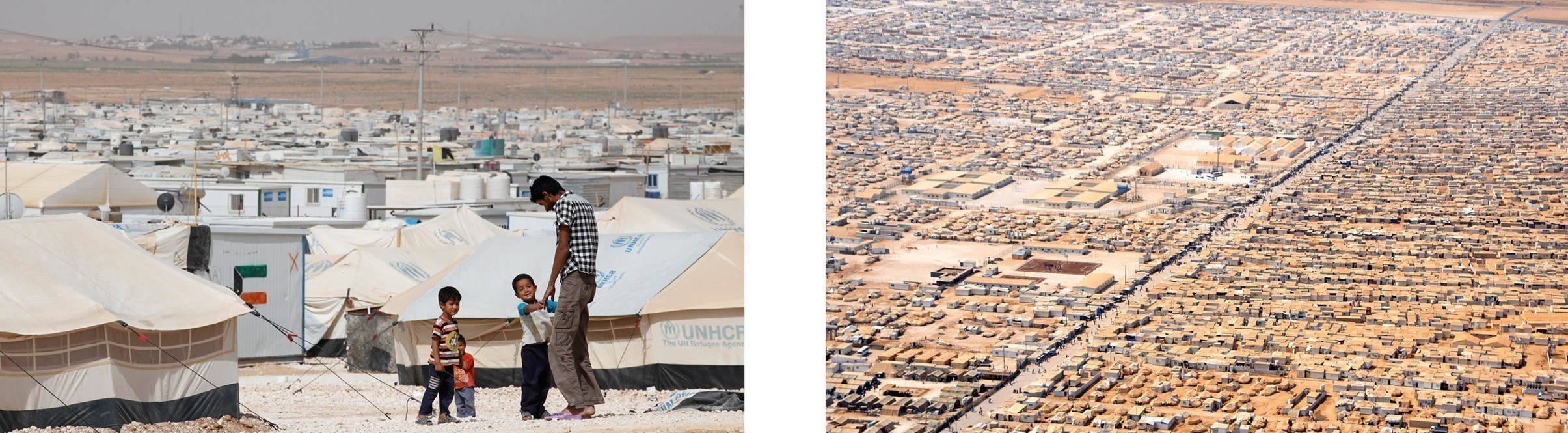

Images: (L) Daily Life in Zaatari Refugee Camp in Jordan © World Bank Photo Collection (R) A view of the Za'atri camp in Jordan for Syrian refugees as seen on July 18, 2013, from a helicopter carrying U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Jordanian Foreign Minister Nasser Judeh. © State Department photo/ Public Domain

On their long and treacherous journeys over land, refugees were shot, robbed, attacked by dogs, beaten and threatened by local authorities, gangs, and human trafficking rings (Dahlia 2015).

Our respondents reported similar abuses. Elisa, a volunteer with a British grassroots organization that provides medical aid in refugee camps in northern France, spoke to camp residents who had been physically attacked by angry local residents (Elisa 2015). Rawad, a volunteer interpreter in Vienna, met several refugees who had been beaten with truncheons by Hungarian police (Rawad 2015).

Even the most vulnerable weren’t spared from this kind of violent behavior. One night, while transporting refugees from the Serbian border to a UNHCR camp, Aude, the volunteer with Migration Aid, met a father from Afghanistan.

“He was carrying his daughter in his arms; she was about ten and had cerebral palsy. [After sitting in the backseat of the car] he started to tell me about his journey from Afghanistan three weeks before. I was trying to get him to share his story without pushing. But at some point, he stopped talking and I could hear him sobbing in the back. After a while, he told me that they were beaten up by the police in Serbia two days earlier, for no reason, just for the sake of order and control at the border” (Aude 2015).

That night Aude drove more than 125 miles, back and forth between the border and the camp, bringing people like this man and his disabled daughter to safety. She explained that, at the border, refugees were told that the UNHCR camp was a couple of miles up the road. In fact, the camp was more than 12 miles away. After watching exhausted refugees, including pregnant women, the elderly, disabled individuals, and small children, walk for hours in the night, she felt compelled to help.

Magdalena witnessed similar circumstances in Hungary, close to the Austrian border where transportation was interrupted for several miles on the route between Budapest and Vienna. Refugees had to walk towards the Austrian border as trains were overcrowded and timetables weren’t available.

“We drove by in our car full of goods and clothing as well as baby carriers. We handed out as much as we could (we had prepared ready-to-use packages of food and crayons and coloring books for children) and gave families warm jackets and shoes. I particularly remember Wallad, a not even 1-year-old Syrian boy, who was being carried by his mom. My sister gave them a baby carrier and they were just so happy to have a little remedy that would relieve their pain from walking for miles and miles” (Magdalena 2015).

Images: (L) Arrival on Lesvos (R) Tovarnik, Border Serbia/Croatia © Fotomovimiento

Respondents who volunteered on the Greek island of Lesvos reported a shortage of buses between border crossings, registration centers, and transit camps. Upon arrival, the majority of refugees—already exhausted and soaking wet from their arduous crossing—were forced to walk 44 miles from the shoreline to the nearest registration center. Until the end of January, when the Red Cross set up a transit center and minibus service, there were only four buses operating between the shore and the center (Amnesty, 2015; Haga, 2016).

Besides the irregular transportation and missing timetables, several other key problems affected refugees’ transit conditions. In the past year, borders along the land route have suddenly closed, leaving refugees stranded.5 The absence of clear communication between refugees, border authorities, and aid agencies has further worsened these bottlenecks. As a result, local authorities, who often lack the ability and experience to deal with the consequent chaotic situations, have regularly resorted to violence.

International aid organizations have also fallen short. For instance, Aude felt disappointed with the UNHCR and the Red Cross for not responding adequately or efficiently. She is hardly alone. Other respondents reported a lack of international NGO and UNHCR presence in the camps and at the borders. Maaike, a volunteer with a Dutch grassroots organization on Lesvos, accused officials from large aid organizations of using the situation in the refugee camp where she worked as a photo-op. She described how representatives would come in with a selfie-stick, take some photographs, but leave most of the work to volunteers like her.

Maaike also was concerned that donations made to large aid organization often did not reach those who most need the aid.

Although we could not confirm her suspicions, we do know that humanitarian aid that is spent on refugees is often distributed unevenly among nationalities. Last November, Dutch volunteer Kaatje worked for Because We Carry, an organization that hands out baby carriers, clothes, blankets, and food to refugees who arrive by boat in Greece. The first thing she noticed when she arrived in Camp Moria—Lesvos’ main refugee camp—was the division between Syrian and Afghani refugees. While aid organizations were active on the Syrian side, the Afghan side of the camp received virtually no support. This motivated Kaatje and her fellow volunteers to focus primarily on Afghan refugees who are increasingly labeled as economic migrants.6

“I met a family from Afghanistan. A father, mother, and their four children. They arrived at Camp Moria at night; their clothes and shoes were soaking wet. The mother had a large wound on her shin and the father had a two-month-old baby wrapped in a heat blanket. […] I wanted to send them to a medical post, but at that time there was only a medical post on the Syrian side and they didn’t treat this family. It was dark and I didn’t know what to do, so I ran to [our] bus and tried to find dry clothes for all of them. This family really got to me. If it was up to me I would have taken them home. Offer them a hot shower, a good bed, and a warm blanket” (Kaatje 2015).

Images: (L) Macedonian border September, 2015 (R) Refugees at Gevgelija train station in Macedonia, close to the border with Greece July 30, 2015. Public Domain: Freedom House Syrian Refugees

Both the volunteers and the refugees we interviewed said they had witnessed or experienced similar examples of unequal treatment. This stemmed from a number of factors: ethnicity, gender and age (women and children are seen as less threatening and more vulnerable than single males), and the perceived status of “economic migrant” versus “war refugee.”

For example, Schero, a 23-year-old Kurd from Kobane, Syria, explained to us that Kurds in his home country and in neighboring countries historically have been subjected to systematic discrimination and harassment by the government. In Turkey, where tens of thousands of Syrian Kurds from Kobane found refuge, Kurds have been the victims of persistent assaults on their ethnic, cultural, religious identity and economic and political status by successive governments.7 The prevalence of this deep-rooted aversion against the Kurds, an aversion that hasn’t seized since the outbreak of the conflict in Syria, formed an added obstacle for Kurdish refugees in Turkey. For example, Schero was treated disrespectfully by Turkish police after they saw his ethnicity on his passport. The attitude of border officials and locals towards refugees varied along Schero’s route from Kobane to southern Austria, he said. While he had negative experiences in Turkey and Macedonia, he was warmly welcomed in Austria.

Welcoming environments such as the one Schero described in Austria are often created by numerous volunteers, among them many ex-refugees, who try to help and assist in different ways. They distribute food and warm clothing, provide medical care, and act as translators. In Lesvos a group of lifeguards from Spain has been working around the clock to save refugees whose boats have capsized. And in Calais, France, a large group of medical professionals have been volunteering their time and resources to help refugees in desperate need of medical attention. These volunteers would not be able to do their jobs without all the donations made by ordinary citizens. In Austria, for example, the first distribution centers for food and clothes sprung up as soon as the first trains with refugees came in from Hungary. Within days, a vibrant network of shelters and services for refugees was operating, and Austrians from all walks of life were donating their time and goods.

These people, an army of unsung heroes, have filled a void in humanitarian aid. Financed by charities, crowdfunding platforms, and personal savings, grassroots organizations and small NGOs have proven to be especially effective. Where big humanitarian aid organizations and local authorities have been mired in red tape and shirking responsibility, small organizations and individual volunteers have been flexible and efficient. They have adapted adequately to the quickly changing nature of the refugee crisis, and have successfully raised awareness about the plight of refugees. In some cases they have influenced or inspired local governments.

Final destination?

Schero, the young Kurd from Kobane, described how relieved he felt when, in February 2015, he was able to move into an asylum home in Fuerstenfeld, a small town in southern Austria. The psychological trauma of suffering violence and harassment in Syria and while en route to Austria eased for a brief moment when he settled into his new home, his first stable accommodation since leaving his homeland. However, Schero soon realized that the asylum process posed new uncertainties and challenges.

Schero and thousands of other refugees have been living in limbo as they are waiting for their asylum claims to be processed. With the crisis deepening, more refugees have been applying for asylum. Years can go by before an applicant knows if he or she can stay or has to return. Schero, eager to start planning for his future, has returned to the application bureau four times in the past six months, hoping to learn more about his status, but at the time of our interview he was still in the dark. He said he finds it is especially difficult to sit around all day, day in day out, with nothing to do.

Images: (L) Volunteer at train station in Vienna (R) This poster was made by refugees as a “thank you” to all the volunteers and professional responders who have been working at the train station in Vienna. It contains messages, hand prints, names of the children, and some statements about children’s aspirations and feelings. For example, Maha Kasha later wants to study architecture, Bayan wants to become a painter and 12-year-old Nur who arrived without her parents, completely on her own, loves and misses her mother a lot. October 2015 © Magdalena Schwarz

In her 2010 study of children in Danish asylum centers sociologist Kathrine Vitus links the open-ended waiting time—characterized by boredom, powerlessness, restlessness, fatigue and despair—to desubjectification of these children, who are living without a home, and without an identity (Vitus 2010). Based on our interviews, the same rings true for adolescent and adult refugees, who also feel they live neither in the present nor in the future.

Loneliness makes matters worse. Many refugees have been separated from their families. Hamza, a father of four in his mid-forties, fled from his birthplace, Kobane, via Turkey to Austria. His wife and children are still in Istanbul. Hamza told us that he hasn’t seen them in 18 months. Since his arrival in Austria, he has worked hard to get all the paperwork in order, but he isn’t sure when he will be reunited with his family. For refugee families, like Hamza’s, torn apart by war and persecution, the heartache of separation is a daily pain, exacerbated by toughening immigration policies and increasing hostility towards refugees in host countries.

Bert, a volunteer with Vluchtenlingenwerk Oost-Nederland (Refugee Work East Netherlands) in Ulft, works with people who have obtained temporary asylum. He has witnessed firsthand how loneliness and waiting in limbo affect former refugees’ mental health.

“[Refugees with temporary asylum] need psychological support. For example, a man from Syria has been living in Ulft [town in East Netherlands] for the past six months. He has been trying to get his wife and four children to the Netherlands, but unfortunately he has failed to do so—his paper work isn’t in order. He is so disappointed. He smokes more than a pack of cigarettes a day and doesn’t leave the house. In the meantime, a second attempt to reunite with his family has also failed. The house coach [a social worker] is helping him deal with these setbacks and tries to get him to go outside and do things” (Bert 2015).

Fortunately, this Syrian’s house coach monitored his behavior and helped him deal with these setbacks. Other refugees, however, have not been as fortunate. They have to endure family separation, social isolation, post-traumatic stress, and existential fears, such as loss of job and home, without any professional support or guidance.

Uncertain future

It is easy to forget that refugees once had jobs, careers and aspirations for the future. Many of them lived regular lives not so different from most of us—whether in Austria, Germany, or the United States. While war abruptly ended their normal lives, their desire to work and make a living has not stopped.

Still, many have to downgrade their career and their expectations. For instance, Khaled, a 50-year-old Palestinian lawyer, spent most of his adult life in Damascus where he lived with his wife and children. When their house was bombed during the war, the family decided that they couldn’t stay in Syria. Khaled couldn’t afford to bring his whole family, so he painfully resigned to come alone. He hoped to find a job, start a new life and arrange for his family to join him in the nearby future. Even though he loved his work, Khaled said that he already has accepted that he’ll probably never work as a lawyer again.

Sarah, who has worked as a volunteer with Afghan refugees in Afghanistan and Pakistan, was involved in a research project that looked at the experiences of long-term refugee youth. She explained that adult refugees, like Khaled, tend to focus on the next generation.

“In my research, while there were hopes and aspirations, there was also a clear trend that refugee life involved a large economic downturn and lowered quality of life (not knowing the language, no way of having a livelihood using the skills and networks they have back home), and that adults would essentially be a ‘burnt generation’ that would pave the way for the generation afterwards. So for example a famous politically-minded journalist would hope at best to be a taxi driver or cook, working essentially at the bottom and eschewing their chosen career path, in order to support their families” (Sarah 2015).

Younger refugees appear to have greater confidence in the future, especially when they find themselves in a country where people actively try to help refugees integrate. Khaled, a 23-year old Syrian student, fled Damascus three years ago after his university was bombed by the army. His journey led him via the United States to Germany where he now studies computer engineering a university in Berlin. He was reunited with part of his family in Berlin, but unfortunately his father, as well as some other relatives, remain in Syria.

Image: In Fuerstenfeld (Austria), locals and refugees spent an afternoon learning each other´s traditional dances, while sharing thoughts and experiences. A group of local volunteers organize afternoons and excursions like these to welcome refugees from nearby asylum centers/homes. November 2015 © Magdalena Schwarz

When Khaled arrived, he couldn’t speak a word of German, but he learned quickly. He obtained his German language certificate (foreign students can’t enroll in university without this certificate) and he now takes classes taught in German. He said professors and fellow students have been very welcoming, but he still feels apart from them, in that they, understandingly, don’t really grasp how difficult it is to be a foreigner and a former refugee.

“Not many people understand [that I come from a war torn country]…I have difficulties with the language and it is not so easy. I also have problems with my family and they cannot understand that. This is why it is harder for me. But now I am okay with this situation, I am in the second semester now. The first semester was harder but now I have finished the exams with 2.2 grades and I passed all modules and courses. There are a lot of colleagues at my university that were born here and they did not pass those modules and I passed them. This was very good for me, this was positive for me and it is much easier now” (Khaled 2015)

His success story doesn’t end there. Khaled proudly told us he also secured his first job as a junior web developer, with help from a recently launched website that helps refugees find jobs in Germany.

In fact, eager to return the generosity others have expressed towards him, Khaled has been volunteering as an interpreter for a nonprofit in Berlin. In addition, with a team of developers he has created an online platform for refugees where refugees can find landlords who are willing or even eager to rent to refugees.

These landlords may not fully grasp the significance of providing safe, affordable homes to people whose journeys to safety are characterized by hunger, dehydration, exhaustion, hypothermia, heat stroke, violence and hostility. Through our respondents, we have learned that many of these life-threatening challenges are caused by a lack of real-time information, overarching coordinated response, and clear communication between border authorities, aid organizations and refugees themselves.

Uncertainty caused by red tape and a lack of information continue to plague refugees upon arrival in host countries. Many suffer from post-traumatic stress, which is exacerbated by open-ended waiting periods, constantly changing asylum policies, social isolation caused by family separation, a loss of identity and social roles, and increasing hostility towards refugees.

Local and national governments and international humanitarian aid agencies have been preoccupied with numbers, caps on these numbers and questions of who is responsible for refugees’ wellbeing (i.e. passing the buck), there are thousands of passionate people who have stepped up and filled the void in international response by volunteering their time and expertise. They have raised money, resources and awareness about the plight of the refugees. In fact, while politicians have tended to dehumanize the refugee crisis, these volunteers have given the crisis a human face.

The fact that many of these volunteers include former refugees who are eager to help in any way possible underscores the notion that refugees are not just vulnerable or needy people; they are also proud, resilient and capable. With a little bit of assistance, as we’ve seen in the case of 23-year-old Khaled, refugees can be assets to a country instead of a burden.

We would like to thank all of the men and women who participated in this project. We are grateful for their willingness to share their experiences with us.

For donations and further information:

Because We Carry: http://becausewecarry.org

Hummingbird Project: https://www.facebook.com/Hummingbirduk/ and https://chuffed.org/project/thehummingbirdprojectbrighton

Migration Aid: http://www.migrationaid.net/english/

Vluchtelingenwerk: https://www.vluchtelingenwerk.nl/doneren/geef-voor-vluchtelingen

References:

Amnesty International, (2015), Greece: Chaos and squalid conditions face record number of refugees on Lesvos, August 24, 2015 https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2015/08/chaos-and-squalid-conditions-face-record-number-of-refugees-on-lesvos/ (accessed on January 2, 2016).

Dahlia, (2015), Addressing Information and Communications Needs within the Refugee Crisis in the Balkans, http://dahlianet.org/projects/addressing-information-and-communications-needs-within-the-refugee-crisis-in-the-balkans/ (accessed on January, 25 2016).

Haga, Caroline, (2016) “Lesvos: New shoreline transit centre helps migrants upon arrival” 26 January 2016 International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies http://www.ifrc.org/en/news-and-media/news-stories/europe-central-asia/greece/lesvos-new-shoreline-transit-centre-helps-migrants-upon-arrival-71873/ (accessed on Jan. 30 2016).

Robinson, (2016) “Women and children refugee numbers crossing into Europe surge” Financial Times January 20, 2016 - http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/dff3b5ea-bf99-11e5-9fdb-87b8d15baec2.html#axzz3yXxkdMdp

Vitus, Kathrine, (2010) “Waiting time, the de-subjectification of children in Danish asylum centres” Childhood February 2010 vol. 17 no. 1, 26-42.

-

Magdalena Schwarz and Elke Weesjes contributed equally to this article. ↩

-

We spoke with 16 refugees (all male), including one refugee who also volunteered as an interpreter, and seven volunteers (two males and five females) who have worked for a variety of grass roots organizations over the course of 2015, the year the refugee problem became a full-blown global crisis. Although much of the challenges discussed are ongoing, the focus of this article will be on the events of this past year. At the time of the interviews (conducted between October and December 2015 in Dutch, German, and in English), the majority of refugees were living in an asylum center near Fuerstenfeld, a small town in Southern Austria. This asylum center is home to some 50 male refugees from Syria and Iraq. Although our interview project was not meant to be a systematic or large-scale study—we set out to gather preliminary evidence to help understand some of the challenges refugees faced—we acknowledge that our evidence is limited because we couldn’t speak to female refugees. We do not want to reinforce the idea that all refugees are able-bodied men. According to the latest figures, released by the UNHCR, 45 percent of refugees who make the sea crossing into Europe from Turkey are male adults, 21 percent are female adults, and the remaining 34 percent are children. (Robinson, 2016) ↩

-

One of our respondents, Maaike, explained that Turkish smugglers tend to pretend to accompany refugees on their journey, but jump off after a few meters, leaving inexperienced refugees in charge of driving the boat to the Greek coast. ↩

-

Migration Aid is a civil initiative that helps refugees arriving in Central Europe reach their assigned refugee camps or travel onwards. ↩

-

Some temporary or permanent border closings have occurred in years prior to 2015 but the number of countries that tightened their border security or shut their frontiers altogether increased significantly in the past year. ↩

-

Even though Afghans, who represent the second largest group of refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea, also escaped a country torn by fighting, they have received a different welcome than their Syrian counterparts. Germany for example has labeled them as economic migrants because fighting in Afghanistan is not widespread and the country has received large amounts of development aid. Human right groups have expressed concerns that countries such as Germany, but also other European countries, are moving towards a double standard asylum system that is based on nationality and not on an individual’s right to asylum. Because of this shift there is also less financial aid for Afghan refugees. (http://qz.com/568717/afghan-refugees-receive-a-cold-welcome-in-europe/) ↩

-

In July 2015, the UNHCR reported that 25,000 Kurds were living in Suruc (a camp in Turkey) alone. ↩

Elke Weesjes Sabella is former editor of the Natural Hazards Observer. She joined the staff in December 2014 after a brief stint as a correspondent for a United Nations nonprofit. Under her leadership, the Observer was revamped to a more visual format and one that included national and international perspectives on threats facing the world. Weesjes was the editor of the peer-reviewed bimonthly publication United Academics Journal of Social Sciences from 2010 to 2013.

Weesjes Sabella also worked as a research associate for the Center for Disaster and Risk Analysis, formerly located at Colorado State University (although no longer active). In that role, she collected and analyzed data and translated research findings for a broader audience. She played a central role in finalizing the Disaster Preparedness among Childcare Providers in Colorado project, which examines all-hazards preparedness in daycares and in-home childcare across Colorado. She co-authored the report based on the first stage of the project, which was funded by Region VIII of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Weesjes Sabella specializes in cultural memory and neighborhood/community change in times of acute and chronic stress. She has published articles on the impact of drought on farming communities in Kansas, the effects of Superstorm Sandy in Far Rockaway, Queens, urban renewal in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, and health services for vulnerable populations in the South Bronx.

Weesjes Sabella received her PhD from the University of Sussex. Her dissertation, Children of the Red Flag: Growing up in a Communist Family During the Cold War (2012), as well as the majority of her publication record, share the common methodology of understanding culture and identity through oral history.