By: Donovan Finn

The Rockaway Peninsula was hit particularly hard during Sandy. The Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery has allocated up to $21.3 million in Federal Community Development Block Grant–Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) monies to fund eligible recovery and resiliency projects in the Rockaway West Community. © Elke Weesjes

Superstorm Sandy struck the East Coast of the United States in October of 2012, devastating large swaths of the New York and New Jersey metropolitan region. Some especially hard-hit communities have bounced back slowly. As a whole, however, the region rebounded quickly from the storm. Regional recovery was so swift, partially because recovery planners applied some of the hard lessons learned after Hurricane Katrina (Olshansky and Johnson 2014).

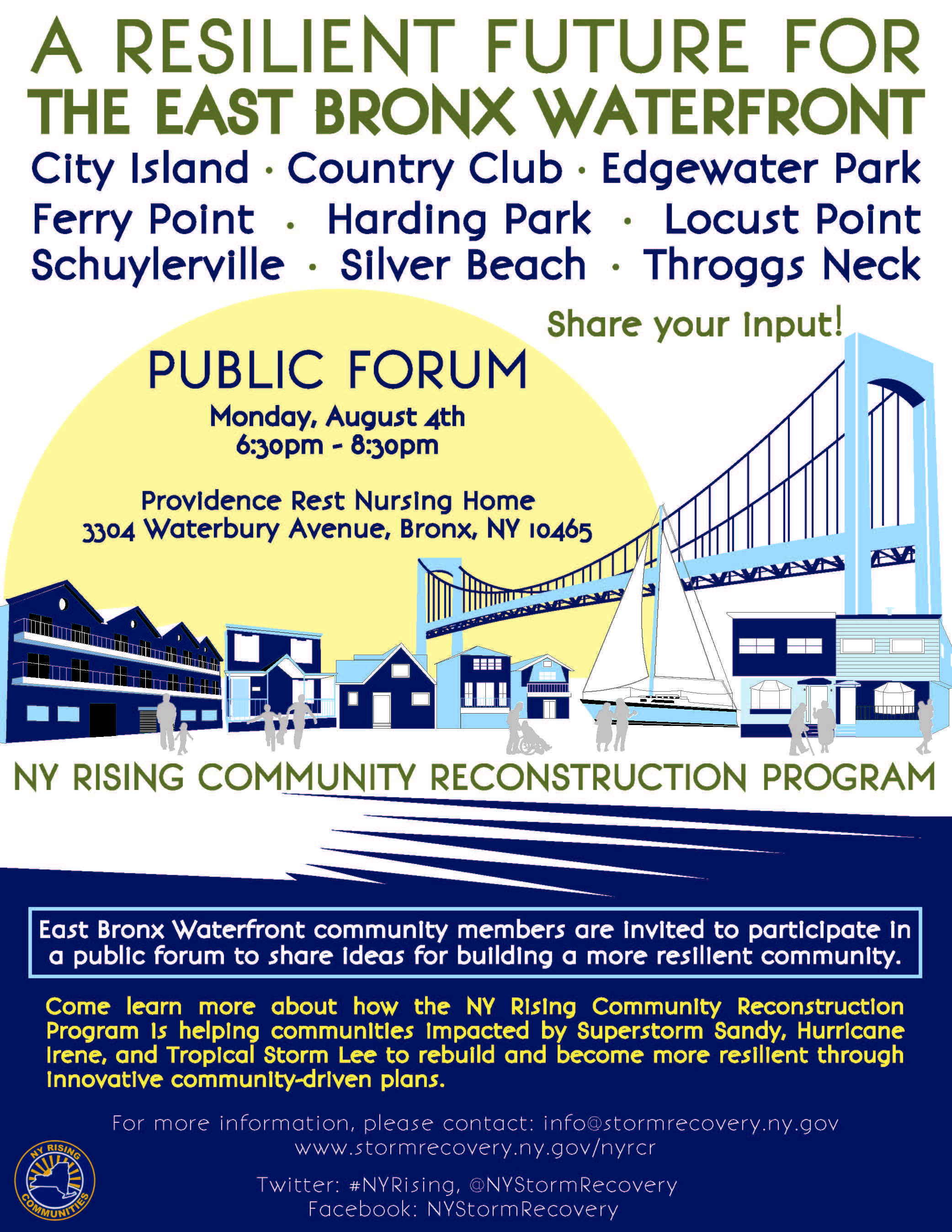

Among these post-Sandy innovations was the state-led New York Rising Community Reconstruction program, a $650 million effort to put rebuilding decisions and future resilience planning in the hands of residents of the hardest hit areas. This ambitious program was among the largest government-led participatory planning efforts ever attempted in the United States. In less than two years, thousands of residents in 66 communities around New York State took part in some 250 public workshops, deciding how to spend their communities’ shares of more than half a billion dollars in federal disaster recovery funds. Since federal rules for spending these relief dollars increasingly emphasize public involvement and resilient rebuilding, New York’s program, if successful, could be a model for future disaster recovery programs.

As an urban planner who studies community participation in the policy-making process, I’ve been closely following the Community Reconstruction program since its inception. Despite occasional hiccups that are inevitable in such an ambitious undertaking, it has so far done many things right in attempting to put real decision-making power in the hands of local residents. Communities were supplied with significant technical support. Project funding was identified before the process began, unlike the vast majority of participatory planning efforts, which typically focus on generating creative solutions and then chase funding after the fact. It filled an existing need in communities where participatory planning of any kind has been largely absent, and it attempted to address rebuilding and resilience in a holistic way. Planners like myself will find a lot to like about how the program was designed. But now it’s time to see where the rubber meets the road. Despite many great ideas and compelling rhetoric about empowered citizen-based decision-making, questions remain and some hard choices will have to be made as the state moves to implement these plans.

Recover from yesterday, plan for tomorrow

When Sandy struck in late 2012, many communities around New York State were still reeling from the effects of Tropical Storm Lee and Hurricane Irene, both of which occurred the previous year. To address the widespread recovery needs from all three disasters, the state developed new recovery and resiliency programs that focused on household, business, infrastructure, and community recovery. All of these were coordinated through the newly created Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery (GOSR). Using the slogan “Recover from yesterday, plan for tomorrow,” the Community Reconstruction program allocated $650 million for community-based planning from New York State’s $1.7 billion in Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) money received from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

Residents of the most severely damaged areas were understandably focused on getting their communities back to normal by rebuilding damaged schools, community centers, roads, and other critical infrastructure. However, by federal mandate, HUD funding also had to be spent protecting against future disasters and it had to include the public in making those spending decisions. To meet these needs, state officials created the Community Reconstruction program using FEMA’s Long Term Community Recovery Planning Process as a model. In total, 66 communities that were affected by Sandy, Lee or Irene each produced a Community Reconstruction Plan with technical help from teams of urban planning, engineering, and environmental consulting firms selected and paid for by the state at a cost of $25 million. Based on assessed damage to community resources, an additional $3 million to $25 million was earmarked for implementation of each plan. State officials anticipated that this money would fund small items in the plans, such as infrastructure repairs, pilot programs, and feasibility studies for larger projects. The GOSR would simultaneously work with communities to find funding for larger projects through grants and debt financing.

Each state-approved, citizen-led Reconstruction Plan contains 30 or so projects, and over half of the almost 2,000 projects across the 66 plans focus on physical infrastructure. New York City’s Red Hook neighborhood, for example, hopes to spend between $1 million and $10 million to repair the Van Brunt Street Pumping Station, which was damaged during Sandy. Ulster County in upstate New York proposes spending $1.2 million to protect its wastewater treatment plant against future flooding. The Long Island village of Bayville wants to build a $425,000 storm barrier to protect the village’s east end from flooding from the Long Island Sound.

However, most of the plans also contain many projects that go beyond rebuilding. Planning committees seized the opportunity to create plans that also addressed broader livability, economic development and sustainability goals such as community gardens, bike lanes, downtown revitalization plans and small business support. Most communities felt strongly that holistic recovery was only possible if such “social resilience” needs were addressed alongside more traditional disaster resilience.

The 66 reconstruction plans were completed with impressive speed, but the real test will now be finding ways to make the plans a reality. In May of 2014 the state hired Hunt, Guillot & Associates (HGA) of Ruston, Louisiana, to guide implementation of the plans based on the firm’s experience with similar work after Hurricane Katrina. HGA and the state will work with local municipalities, counties, non-profits, and other eligible sub-recipients to spend each community’s allotted portion of the implementation funding by the year 2020. But many challenges await. Paradoxically, it is the very aspects that were most laudable about the planning process that now complicate implementation.

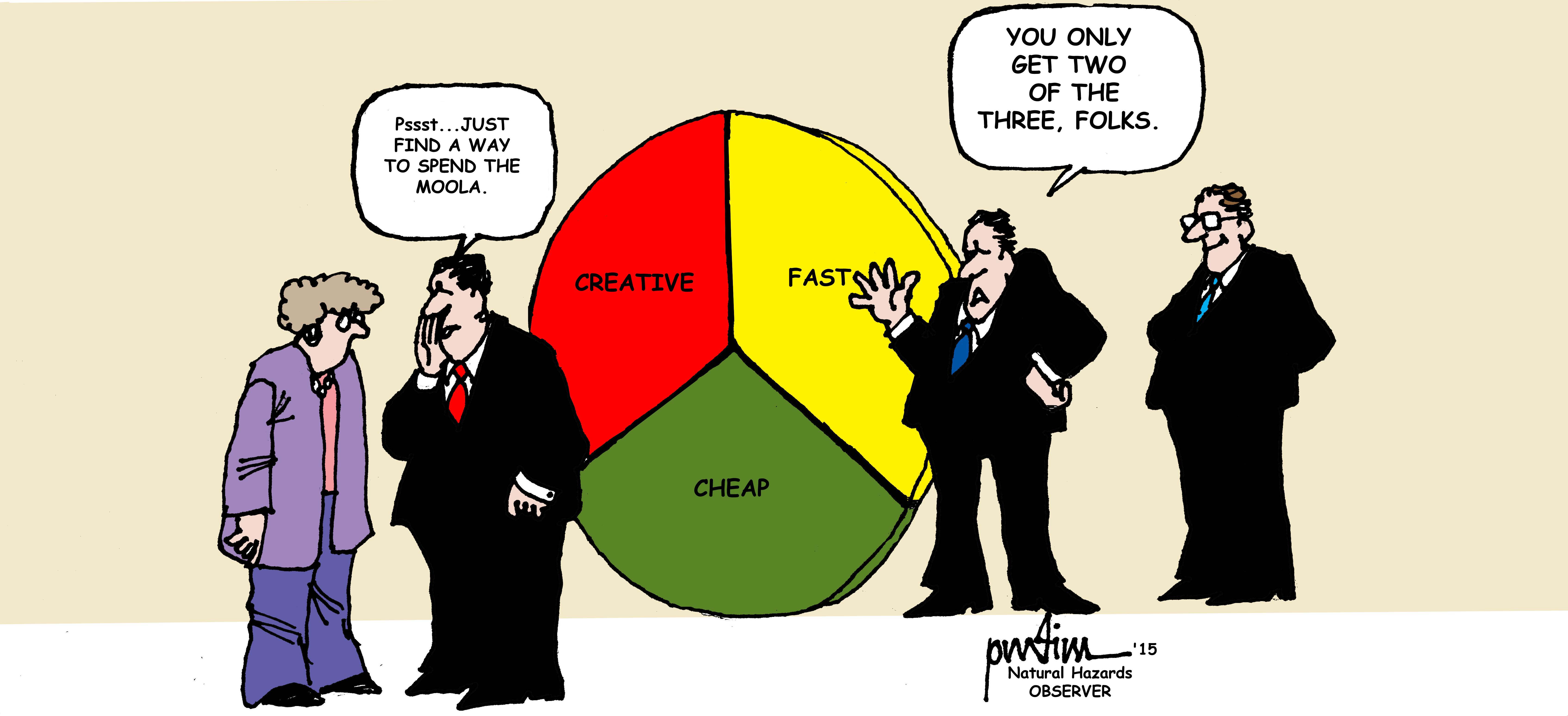

This program attempted to give regular citizens real decision-making power about recovery spending, but time constraints and a focus on grassroots participation may have actually limited the possibility of thinking outside the box about what those solutions could be. While the public, including Planning Committee members, are experts on their local communities, they are not necessarily experts on disaster recovery. As one committee member from Long Island explained to me, this shortfall made it difficult to develop innovative projects because the committee simply lacked the technical skills to come up with or evaluate creative resilience strategies. In the end, he said, their consultant suggested that creative problem-solving would take more time than the state was allotting, and instead counseled a more pragmatic approach: “Just find a way to spend the money.” This tension between innovation and speed is not unique to New York. It is common in post-disaster situations. Creativity takes time and entails risk. It means communities must change. Rebuilding exactly as before is faster and feels safely familiar. Yet, if the Community Reconstruction process mostly ends up just replicating pre-storm conditions, it risks failing to address looming resiliency needs of vulnerable communities.

Of course, many communities have proposed projects that go beyond a narrow vision of rebuilding, encompassing a broad range of social and economic issues. These tactics face their own challenges. For instance, the Community Reconstruction program is run by the state, but it still relies on federal money. That money has strict limits on the kinds of disaster-specific recovery projects it can be used for, and it favors replacement over innovation, and hard infrastructure projects over economic and social resiliency programs. So, while many Community Reconstruction Plans do contain innovative projects addressing holistic recovery and resilience, those will likely need to be funded by other sources, which have not yet been identified and have been slow to emerge.

In attempting to give autonomy to local residents, the program also did not articulate a clear strategy for how plan goals would be achieved. The plans are merely advisory, relying mostly on governmental agencies for actual implementation, from the Army Corps of Engineers to local land use planning departments. As one planning consultant told a Planning Committee in a New York City neighborhood during a discussion of development restrictions along the waterfront, “That’s zoning. Don’t go there.” But sadly, plans will only be successful if they do “go there” and are able to influence local, state and federal spending and policy. Otherwise, they are merely good ideas wasting space on a bureaucrat’s shelf.

There is just not enough funding available today to achieve the ambitious visions the plans represent

Finally, and probably most critically, there is just not enough funding available today to achieve the ambitious visions the plans represent. The $650 million allotted to the program is approximately one-third of New York State’s first tranche of federal recovery funding. It sounds like a lot of money, but it doesn’t go very far in such a large state so heavily impacted by these three major storms. Infrastructure projects alone–building bulkheads, hardening utilities, strengthening storm-water management–dwarf the $650 million available, not to mention the social and economic resilience projects for which funding sources are not even identified. Filling these gaps is now the main task of the Office of Storm Recovery.

Those challenges were perhaps best summed up by Aldean Moore, co-chair of the program’s Rockaway East planning committee. In April of 2014, New York held its second annual Reconstruction Conference at which Moore, in front of hundreds of state and local officials, recounted his community’s Sandy experiences and praised New York Governor Andrew Cuomo for developing the Community Reconstruction program. Moore concluded his comments to the governor with a joke that drew uproarious laughter but was sobering: “And just in case you don’t get a chance to ask us if we need more money…we need more money.”

From Opportunity to Action

Disaster recovery is an emotional process. The Community Reconstruction program was certainly a way for community members to channel those emotions productively. I saw one planning committee member–a stoic, middle-aged professional–cry openly when saying goodbye to his committee’s planning consultant at their final meeting. Other committee members have become more engaged in their communities as a result of their role in the process, running for elected office or forming new advocacy groups. Many of the consultants involved are quick to heap praise on community members for their passion, commitment and creativity. Clearly the process served a sort of cathartic function, at the very least.

But such processes must be more than a Band-Aid. They have to provide real fixes. New York City Council member Donovan Richards represents a mostly low-income part of the Rockaway peninsula that was heavily damaged by the storm. He explained to me that in his opinion, the responsibility of government after a traumatic event like Sandy is to channel the pain felt by communities into something productive, or as he put it, “To find opportunity through chaos.” Certainly, in the Rockaways and statewide, the Community Reconstruction program has shown that the state can do just that. In two years substantial progress has been made on paper. The opportunities are real and the commitment seems genuine. Now the final challenge remains: to move from opportunity to action.

Acknowledgement

Research for this article was supported in part by the National Science Foundation (award # CMMI-1335109). All opinions, findings, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.

References

Olshansky, R. B., L.A. Johnson. 2014 “The Evolution of the Federal Role in Supporting Community Recovery After U.S. Disasters.” Journal of the American Planning Association. Volume 80, Issue 4.

Donovan Finn is an associate professor in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University where he directs the undergraduate program in environmental design, policy, and planning. His research focuses on urban climate adaptation, long term disaster recovery, and climate justice. He received his PhD and master's degrees in urban planning from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and his undergraduate degree from the University of Kansas. He has been an early career faculty innovator at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the Science and Resilience Institute at Jamaica Bay.