Skid Row 2007 © Abhijit Patil

When I first moved to Los Angeles in 2011 to become a researcher with the Veterans Emergency Management Evaluation Center (VEMEC), little did I know, that I would be conducting field research in Skid Row, home to the nation’s largest concentration of unsheltered homeless.

Unsheltered homeless populations live outdoors and so are among one of the most at-risk groups during disasters and face imminent physical danger during storms, wildfires, and extreme temperature events. Adding to the problem is the fact that rates of mental and physical disabilities and substance dependency are high among the homeless, heightening the challenges they face during and after disasters. Despite these compounded risks, homeless individuals’ distinct needs are often overlooked in disaster planning, response, and recovery. And that’s not all—these vulnerable individuals have often been barred from accessing benefits intended for victims of disaster displacement, including disaster shelters.

Our research team at VEMEC first learned of the exclusion of homeless populations from disaster relief and recovery resources during a panel at our 2011 Department of Veterans Affairs’ Comprehensive Emergency Management Program Evaluation and Research Conference. We heard stories of emergency managers answering calls from homeless people stranded outdoors in Florida during Hurricane Jeanne in 2004 and being trapped in flooded encampments during flash flooding in Tennessee. Moved by these stories, the VEMEC team joined with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) to begin discussing solutions and approaches to address this issue with experts in the field of homelessness and emergency management. In the past four years, we have collected tools, best practices, guidelines, and resources to help providers of health care and social services collaborate effectively with emergency managers and disaster relief providers and ensure that homeless populations and their needs are included in disaster planning1

These efforts culminated in the creation of a Toolkit for Integrating Homeless Populations into Disaster Preparedness, Response, and Recovery, which will be released to the public in January 2016.

Faced with the reality of homelessness

While I could have learned about homelessness and its impact on disaster vulnerability anywhere in the United States, living in the city of Los Angeles—with its thousands of homeless individuals living in tents, cars, and makeshift shacks—has afforded me unique insights into the daily challenges homeless individuals face.

The harsh reality of homeless people’s daily lives became especially clear when I volunteered for the biannual 2013 Point-in-Time (PIT) homeless count2 on L.A.’s skid row, a 54-block area of downtown L.A. My research had already taken me to the area’s social service organizations, where I interviewed leaders and staff, so I wasn’t a stranger to the conditions in which people lived. I had seen the sidewalks covered with tents, tarps, and mattresses and the shopping carts filled with residents’ possessions. But I had yet to learn the lessons that the survey, which would bring me closer to my homeless neighbors than I’d ever been, would reveal.

From 8 p.m. to midnight on three nights in January, I joined several thousand of my fellow Angelinos in braving the cold (by California standards) temperatures to administer the PIT count survey. PIT count organizers had assigned us areas of homeless sidewalk encampments to survey. Our goal was documenting respondents’ names, taking photos, and examining their needs so that homeless service organizations could provide outreach and assistance to them in the future.

Volunteering for the PIT count was an amazing and humbling experience. Our team was headed by a veteran who worked as a drug counselor at a skid row organization. The desolate streets were lined with warehouses and abandoned buildings. Rats startled us as they scampered along the rough concrete while we walked the two blocks to our survey site. I realized there was no way I could survive sleeping on these streets for even a single night without being depressed or frightened.

Several of those surveyed were veterans—even some of my fellow surveyors were homeless veterans trying to help others. The first night, we met a veteran who has been sleeping on the skid row streets for more than 20 years. The second night he recognized us and came over. By then, we had VA outreach forms that enabled us to connect veterans with available services. We were also accompanied by Vet Hunters, a non-profit organization located in South El Monte, California, that helps homeless veterans obtain housing and other services.

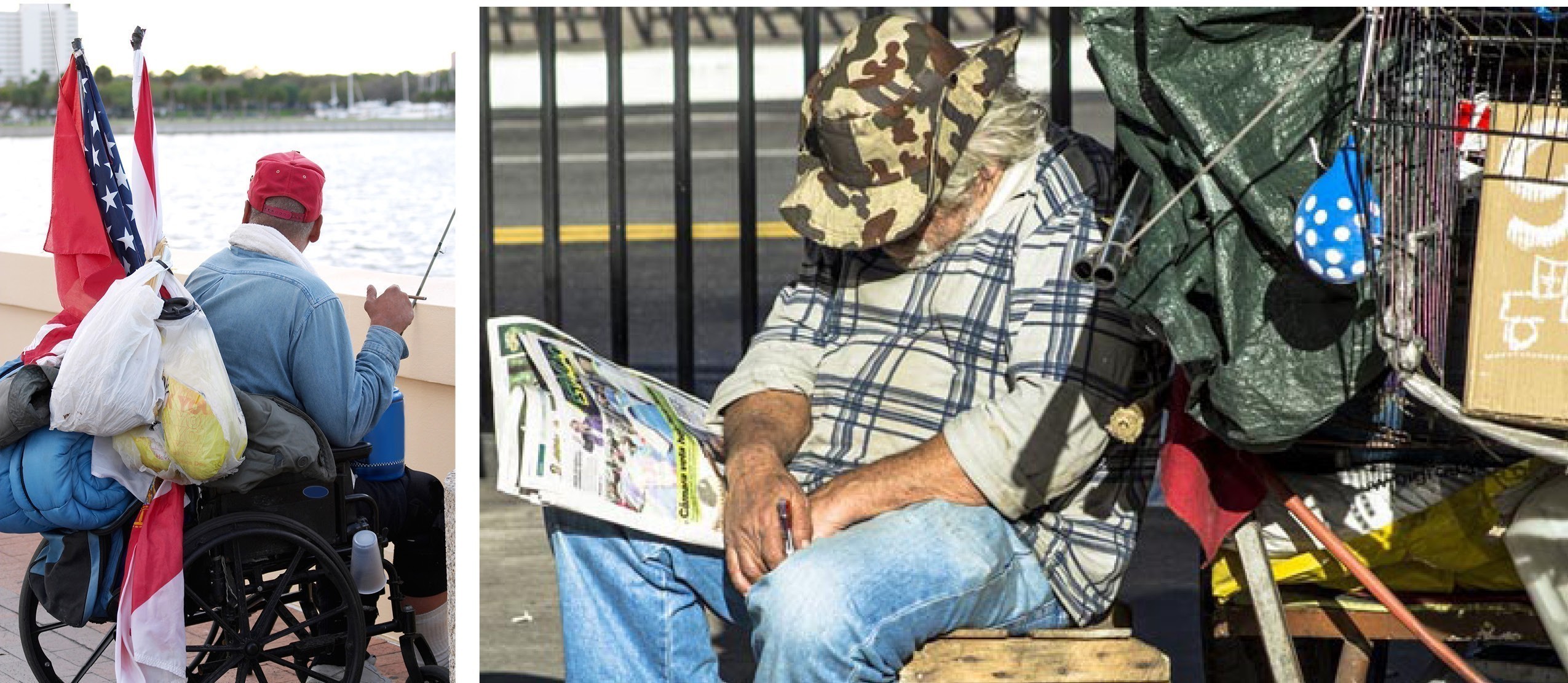

Homeless Veterans © VEMEC

The founder of Vet Hunters, Joe Leal, was part of our team that night. Leal showed the veteran the VA form and asked him about his situation: “How long have you been homeless?” Leal asked. The veteran let out an audible sigh in response and said nothing else. Leal repeated the sigh, saying, “When I hear that, that tells me you’ve been out here for years.” “I’ve been out here half my life,” the veteran responded.

Leal gave him shoes and socks—a much appreciated gift—and asked him whether he had ever gone to the VA for health care or housing assistance. The veteran explained that the last time he was at the VA was five years ago and hadn’t heard of their housing programs. We tried to get him to fill out the VA form, but he said, “I don’t have time. I’ve got to get back to my spot before someone else takes it.”

Things that we take for granted—shoes and socks—are items vital for survival for individuals experiencing homelessness.

As he departed, Leal said, “That’s okay. At least we’ve got his name. We’ll come back on our own time and look for him again. And we got him some shoes and socks.” As a disaster researcher, I thought of the lessons I learned from that brief conversation. First, things that we take for granted—shoes and socks—are items vital for survival for individuals experiencing homelessness. Second, since he had previously made use of the VA we knew he was eligible for VA health care, and possibly for VA housing assistance and other benefits that could help economically disadvantaged veterans recover from disaster. This led me to realize that in a disaster, it would be valuable for a case manager to ask about veteran status. Third, outreach to homeless individuals is a tougher job than it appears because of the everyday challenges they face on the streets. Although we would like to think of it as a simple matter of filling out a form that only takes a few minutes, the homeless veteran engaged in a cost-benefit analysis of weighing the risk of losing his bed or tent spot for the night—a loss that could have devastating consequences to his health, safety, and survival. It’s important to remember this perspective. In disaster planning, similar oversights can easily occur if we don’t include those who are familiar with the daily routines of homeless people when key decisions are made.

Besides gaining insights into the reality of homelessness, I also volunteered for the PIT count because I wanted to help collect the data that decision makers use to create policies concerning the homeless. This data helps identify trends that cause planners to think more specifically about the needs of the homeless. In turn, while developing the Toolkit, knowing the trends in homelessness helped us identify subpopulations of homeless individuals—for instance, people with disabilities, or people with who might not evacuate without their pets—and consider their needs as we developed guidance for emergency planners.

Disaster risk

The increasing homeless population in LA County is an especially worrying trend. Driven by soaring rents, low wages, and high unemployment, the number of homeless grew 12 percent from 39,463 to 44,359 in the past two years. The unsheltered segment of this population (31,018) has increased an astounding 23 percent since the 2013 PIT Count (LAHSA 2015). This trend underscores the urgency and importance of creating local disaster response plans that include the needs and circumstances of the homeless. Planners, should consider, for example, that unsheltered individuals (like the veteran I met on skid row) might be reluctant to evacuate because they risk of losing a sleeping space or possessions. It should be recognized that they have a more difficult time being prepared, because they might not be able to stockpile supplies or take other measures to protect themselves during disaster. Nor do they always have access to computers, newspapers, and televisions where they can get disaster warnings (Edgington 2014). Trust can also be an issue—individuals who are undocumented, who struggle with addiction or mental health problems, or who have a history of incarceration might not trust the authorities who deliver disaster information.

Gin with her group at the Skid Row Homeless Count © June Gin

Even those individuals who actively seek help often don’t receive it, or receive it too late. There are many examples of homeless individuals being denied access to disaster resources. The Federal Emergency Management Agency declared homeless people ineligible for disaster relief and housing assistance (Tierney 2007; Phillips 1989) during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake in California. There are multiple examples of the homeless being turned away from disaster shelters—in the Loma Prieta quake, during Hurricane Andrew in 1992, and most recently during Superstorm Sandy in 2012. Instead, these individuals are steered toward existing homeless shelters, even though the disaster-specific shelters provide more comprehensive services (i.e. remaining open around the clock and offering three meals a day).

Similarly, the pre-disaster homeless individuals were denied entry to American Red Cross disaster shelters during the 2013 Colorado Floods until Red Cross officials instructed volunteers not to deny entry to anyone based on housing status (Vickery 2014). During severe storms in 2014 in Pensacola, Florida, Red Cross and FEMA damage assessments initially overlooked the damage that homeless encampments had sustained. It wasn’t until two weeks later that encampment residents found their way to FEMA officials and received much needed aid (Adamo 2014).

Simply living outdoors poses a separate set of physical risks in disasters. The unsheltered homeless are especially susceptible to extreme weather events, such as temperature extremes, storms, floods, and wildfires, which are likely to become more frequent with climate change (Brodie and Svoboda 2009). Homeless encampments frequently flood because they tend to be located in low-lying areas where the land is less desirable land and more likely to be vacant. For example, in December 2014, LA firefighters rescued a homeless couple who lived on the banks of the LA river when unexpected rainstorms caused the water to swell and surge. It took an elite swift water rescue team two hours to bring the husband and wife to safety (Klein and Klemack 2014).

Given that these factors increase disaster vulnerability, homeless individuals need extra assistance from community-based organizations, disaster relief providers, and government agencies. Communities, however, are not always well prepared to address their needs. The homeless are often excluded from relief efforts after disasters, thanks at least in part to poor pre-event planning and a lack of coordination and resources.

But there is hope. Awareness is growing, and more and more communities around the country are developing initiatives to address disaster needs of people experiencing homelessness. Solutions include improving coordination and communication between community organizations, local emergency management agencies, disaster relief organizations, and healthcare providers. In L.A., homeless service providers worked with the Los Angeles Police Department to create the Skid Row Interagency Disaster Plan that ensures organizations providing shelter, housing, and meals are able to work together and communicate with city emergency responders during an event.

The Toolkit

Since 2011, VEMEC team has worked with federal partners to identify successful local initiatives and launch a national conversation about how to ensure that other communities will follow suit. Together we identified three areas with the greatest need for improvement:

- Coordination and Communications

- Technical Assistance and Training for CBOs

- Guidance for Health Care Providers

We invited experts to speak about solutions and next steps at a 2013 Workshop to Integrate Homeless Populations into Disaster Preparedness, Planning and Response. Based on their feedback, ASPR and VEMEC decided to develop a Toolkit aimed at practitioners—emergency managers, disaster professionals, community-based service providers, and healthcare providers—to help them plan, prepare, and work together to care for homeless populations during disasters.

We formed workgroups around the three priority areas. ASPR led the workgroup that developed guidance for health care providers, and the HUD SNAPS office, along with VEMEC, wrote guidelines and recommendations to improve coordination and communication between sectors, including public health departments, CBOs, and local emergency managers who all have a stake in caring for homeless populations during disasters. I worked with partners to identify existing best practices in technical assistance and training aimed at helping CBOs prepare and develop Continuity of Operations3 plans.

Our three workgroups began with a literature review, but quickly found a lack of written material when we looked for recommendations about how disaster-care for homeless populations could be improved. Undeterred, we turned to experts for further guidance. The ASPR team collaborated with a group of experts that included health care providers, researchers, federal grants administrators, emergency managers, and pubic health officials. The SNAPS and VEMEC teams interviewed more than 30 state and local emergency managers, executive directors and staff at CBO providers, and members of the Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters (VOAD). We spoke to founders of innovative community initiatives including L.A.’s Skid Row Interagency Disaster Collaborative.

The Toolkit will be released to the public in January 2016. As we disseminate this living document to emergency managers, service providers, and healthcare providers nationwide, we hope to hear about and incorporate other ways communities have integrated homeless populations in disaster planning. We invite practitioners, policymakers, and researchers to share their experiences and contribute their knowledge to this emerging field. Next, we intend to translate the Toolkit into a web-based training program. We believe the Toolkit will offer communities across the country a menu of ideas for including the homeless in their own disaster preparedness, response, and recovery plans.

Conclusion

When I heard about homeless people having to be rescued from the raging floodwaters of the L.A. River, I think of the homeless veteran that night on skid row who couldn’t afford to stay another minute to complete paperwork that might lead to housing after two decades on the streets. People like him will continue to make choices shaped by the reality of daily survival—choices that may increase their disaster vulnerability or delay their disaster recovery. These individuals will continue to be vulnerable to disasters until we are able to end homelessness.

Until then, the Toolkit builds these lessons. As one emergency manager framed it: “The population you don’t plan for before a disaster is the population that will exhaust 90 percent of your resources during a disaster.” This lesson was not lost on the team of firefighters who risked their own lives rescuing the homeless couple from the river. The Toolkit, which outlines ways that emergency managers can improve risk communication to homeless individuals and work closely with homeless service agencies, offers ideas to help communities avert such harrowing events and future tragedies. Until we are able to end homelessness in the US, communities will need these and other lessons to help their homeless neighbors weather the dangers of disasters and rebuild their lives afterwards.

References

Adamo, Alessa (American Red Cross Florida volunteer), unpublished written communication, 2014.

Edgington, Sabrina, September 2014, “Integrating Homeless Service Providers and Clients in Disaster Preparedness, Response, and Recovery.” Issue Brief for National Health Care for the Homeless Council. HUD Exchange Website, 2014. https://www.hudexchange.info/hdx/guides/pit-hic/ (Accessed on November 25, 2015)

Klein, Asher, and John Cadiz Klemack, December 2, 2014, “Homeless couple rescued from raging LA River” NBC4 News http://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/Rescuer-Dives-Into-Swollen-LA-River-Searching-for-Men-Reported-Clinging-to-Trees-285634601.html#comments (Accessed on November 25, 2015).

Brenda Phillips, 1989. “Shelter and housing of low-income minority groups in Santa Cruz after the Loma Prieta Earthquake.” The Loma

Prieta, California, Earthquake of October 17, 1989—Recovery, Mitigation, and Reconstruction, Joanne M. Nigg, Editor. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1553-D.

Ramin, Brodie and Tomislav Svoboda (2009). “Health of the Homeless and Climate Change”, Journal of Urban Health. 86(4): p. 654-664.

Kathleen Tierney, 2007. “From the Margins to the Mainstream?: Disaster Research at the Crossroads.” American Behavioral Scientist. LAHSA 2015 http://www.lahsa.org/homelesscount_results (Accessed on November 25, 2015)

Jamie Vickery, presentation at the 2014 American Sociological Association annual meeting.

-

In creating the toolkit, the VEMEC team has worked with ASPR’s At-Risk Populations, Behavioral Health and Community Resilience Division (ABC) and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Special Needs Assistance Program (SNAPS) Office ↩

-

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) requires all Continuums of Care—local planning bodies that coordinate all homelessness services in a community—to conduct a Point-in-Time (PIT) count of unsheltered homeless persons every other year (odd numbered years) ↩

-

A Continuity of Operations Plan (COOP) is a document that an agency or organization uses to ensure that its most critical functions can continue to be performed during emergencies, and resume after disruption. While it is often a government document, disaster planners note that non-profit organizations should also have COOPs. ↩

June Gin is a research health scientist at the Veterans Emergency Management Evaluation Center. She works to create evidence-based tools and resources to improve disaster preparedness in community-based organizations serving homeless veterans and leads projects to strengthen the preparedness of safety net organizations serving individuals experiencing homelessness.