© Wiredforlego 2012

On October 23, 2006, a newly formed group of activists, local residents, and homeless individuals called Take Back the Land occupied a vacant lot in the Liberty City section of Miami, Florida. At that time, the plot of land had sat vacant for about eight years after low-income housing was demolished, yet not replaced with the affordable homes that the city had promised. Miami-Dade County had allocated $8.5 million that was wasted on architects, consultants and other overhead.

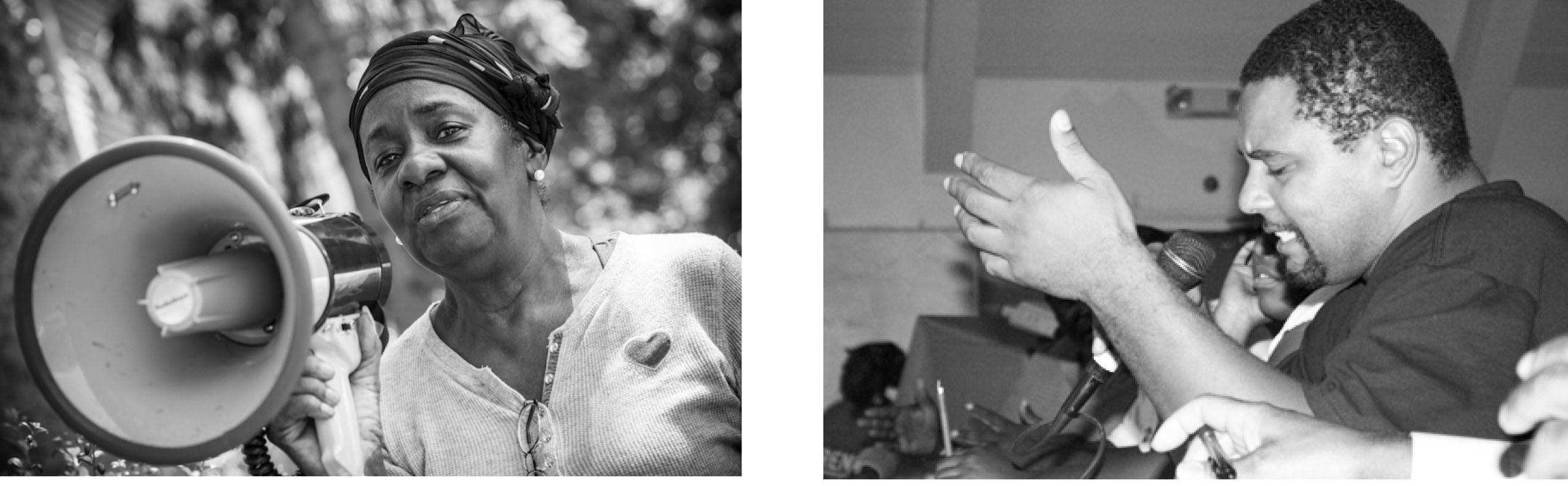

“The county is stealing, the city is not rebuilding, what are we supposed to do?” said Max Rameau, Take Back the Land co-founder in a 2007 interview with Times, “We wouldn’t be able to get away with this if the government wasn’t involved in corruption and there were viable alternatives”(Klarreich 2007).

Rameau and his peers, in response to the low-income housing crisis that gripped Miami in the early 2000s, built a fully functioning urban shanty town and called it Umoja Village, named after the Swahili word for unity. Over the following six months, more than 150 formerly homeless people found a place to sleep and to call home.

The Village was run like a well-oiled machine. Residents voted on the rules of their community and were part of its development and maintenance. They cooked and cleaned and built showers, a library, and a welcome center. Some used the physical safety and food security to recharge and save up money in order to secure permanent housing. While living on the land, several residents who struggled with alcohol and drug dependency became clean and returned to school or found employment.

(L) Victory on Barlett Street Rochester © Take Back the Land Rochester, (R) Max Rameau, US HUD Take Over Town Hall © Miami Workers Center

Police, the city of Miami, and Miami-Dade County officials were unable to evict the residents or organizers due to the landmark agreement Pottinger v. City of Miami, a lawsuit over police harassment of the homeless. The suit was filed in 1988 by the American Civil Liberties Union on behalf of all homeless people living in the Miami. The agreement, which was finally reached in 1998, placed limits on the power of Miami City police officers to arrest homeless individuals for committing certain life-sustaining conduct misdemeanors, such as cooking over an open fire or blocking a sidewalk. It also requires police and other city officials to respect homeless people’s property rights. Furthermore, the judge decided that homeless individuals who had been wrongly arrested between 1984 and 1998 would receive $1,500 in compensation.

Aware of these rights, Taking Back the Land was able to create Umoja. The creation of the Village was a protest as well as a solution to the housing shortage. The initiative enjoyed broad support in the community and was featured in national newspapers. Because of this widespread recognition and support, Umoja Village was able to withstand numerous attempts by government officials, who tried to find ways around the Pottinger agreement to evict its residents.

In April 2007, the Village celebrated its six-month anniversary by announcing several campaigns, including the replacement of the wood shanties with more durable structures; building a water well; engaging in local anti-gentrification and pro-housing campaigns; demanding legal rights to the land from the City of Miami; acquiring land and build low-income housing.

Just three days after its anniversary, an unexplained fire burned Umoja Village down to the ground. There were no casualties or injuries, although Miami police arrested 11 residents and activists for attempting to remain on the land. The city erected a barbed wire fence around the property that same day.

In response, Take Back the Land regrouped and initiated a bold campaign, which sparked a national movement that is still active today. The group “liberates” vacant government owned and foreclosed homes in Miami and moves homeless families into them. In addition, the organization wages so-called eviction defenses by physically blockading homes to prevent police from evicting families.

Rather than feeling defeated, Rameau felt encouraged to continue his fight against homelessness.

“Umoja Village challenged our sense of what was possible here,” he said in a 2011 interview with Miami New Times. “People realized you don’t have to ask the government to change—you can force it to change” (Elfrink 2011).

Rameau isn’t concerned about the fact that Take Back the Land is basically promoting illegal squatting. “Take Back the Land’s primary concern is not with what is legal or illegal, but what is moral and immoral,” Rameau said during an interview on PBS. “And we think it is immoral to have vacant homes on one side of the street and homeless people with nowhere to live on the other” (PBS 2009).

At the time of the Pottinger agreement there were roughly 8,000 sheltered and unsheltered homeless in Miami-Dade County. This number has decreased to 4,152 today, partially due to improved economic conditions but also to local efforts supported by the state. The county is making progress, but, as the numbers show, there is still a lot of work to be done.

Taking Back the Land activists promised not to back off from its campaigns until homelessness in the United States is eradicated.

References & Further Reading:

Elfrink, Tim. “Controversial Miami Activist Max Rameau Leaves Town” Miami New Times June 30, 2011. http://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/controversial-miami-activist-max-rameau-leaves-town-6381436 (accessed on November 20, 2015). Klarreich, Kathie. “The Battle Over Miami’s Shantytown” Times Thursday January 18, 2007 http://content.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1580473,00.html (accessed on November 20, 2015). PBS, “Homes for the Homeless” broadcast June 26, 2009 http://www.pbs.org/now/shows/526/ (accessed on November 20, 2015). Rameau, Max. 2012. Take Back the Land: Land Gentrification, and the Umoja Village Shantytown. AK Press, Edinburgh, Oakland, Baltimore.

Elke Weesjes Sabella is former editor of the Natural Hazards Observer. She joined the staff in December 2014 after a brief stint as a correspondent for a United Nations nonprofit. Under her leadership, the Observer was revamped to a more visual format and one that included national and international perspectives on threats facing the world. Weesjes was the editor of the peer-reviewed bimonthly publication United Academics Journal of Social Sciences from 2010 to 2013.

Weesjes Sabella also worked as a research associate for the Center for Disaster and Risk Analysis, formerly located at Colorado State University (although no longer active). In that role, she collected and analyzed data and translated research findings for a broader audience. She played a central role in finalizing the Disaster Preparedness among Childcare Providers in Colorado project, which examines all-hazards preparedness in daycares and in-home childcare across Colorado. She co-authored the report based on the first stage of the project, which was funded by Region VIII of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Weesjes Sabella specializes in cultural memory and neighborhood/community change in times of acute and chronic stress. She has published articles on the impact of drought on farming communities in Kansas, the effects of Superstorm Sandy in Far Rockaway, Queens, urban renewal in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, and health services for vulnerable populations in the South Bronx.

Weesjes Sabella received her PhD from the University of Sussex. Her dissertation, Children of the Red Flag: Growing up in a Communist Family During the Cold War (2012), as well as the majority of her publication record, share the common methodology of understanding culture and identity through oral history.