A Decision Framework for Equitable Use of Federal Funds in Buyout Programs

Publication Date: 2025

Abstract

Disaster losses are increasing rapidly in coastal regions, highlighting the pressing need for effective mitigation strategies. The voluntary buyout program is an effective approach to reducing risk from future flooding, often funded by federal grants after disasters. However, following a disaster, decision-making tends to be reactive, potentially leading to a haphazard selection of properties and households for program participation. It is crucial for local governments in charge of these programs to be informed about who may or may not benefit from program participation when deciding which properties to prioritize. Incorporating social equity in those decisions can help prevent unintended consequences for the program participants, such as financial constraints, long waiting time, or loss of social network upon relocation. With a mixed-methods research design involving interviews with buyout practitioners and experts, a comprehensive literature review and synthesis of past studies and policies on voluntary buyouts and relocation, and advanced hazard models, we develop and test a decision framework to support local practitioners in considering equity when selecting buyout properties. The findings from this study can ultimately lead to improved outcomes for households participating in the federal buyout program.

Introduction

Voluntary residential property acquisition (also referred to as buyouts) is an effective flood mitigation strategy as it offers a permanent solution to flooding risks by removing vulnerable structures from floodplains. Despite the benefits of buyouts, in practice, these programs are sometimes inadequately launched and administered, revealing disparities in both process and outcome. For example, the program often prioritizes properties in communities where the residents are predominantly people of color or low income, but it usually takes years for participating households to complete the program and they often pay considerable amounts out of pocket, particularly if they want to relocate to outside of flood plains (Mach et al., 20191; McGhee et al., 20192; Sanders, 20223; Siders, 20194; Siders & Gerber-Chavez, 20215; Weber & Moore, 20196). Together these factors lead to the potential for inequitable implementation of buyout projects.

A purposeful voluntary buyout program should align with principles of social justice and address concerns raised by researchers and practitioners about the program's potential inequitable outcomes (Horn, 20237; Siders, 2019). Buyout decisions made by local government practitioners play a pivotal role in shaping the social fabric of communities and have the potential to impact households psychologically, socially, and economically (Siders, 2019). There is a need for a robust framework that can inform decisions, facilitate equitable selection and implementation of buyouts, pursue policy adjustments, and exhibit flexibility and adaptability to the unique contexts of different communities. A decision framework is a structured approach with clear goals to synthesize information and facilitate decision-making processes. In this study, we employ a systematic, data-driven, and collaborative approach to develop such a decision framework for equitable use of federal funds for buyouts. Our study is mainly focused on buyout programs funded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Our framework aims to support local practitioners in identifying residential properties for the buyout program based on the community’s priorities. It also reveals the potential equity outcomes for buyout participants. We developed this framework by conducting a comprehensive literature review and synthesis of past studies and policies on voluntary buyouts and relocation, as well as interviewing experts in local and state government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and academia. Then, we tested the framework by applying it to the City of Galveston, TX, using the Interdependent Networked Community Resilience Modeling Environment (IN-CORE) platform, which is an open-source, interdisciplinary computational environment that models the impact of natural hazards on communities and allows the comparison of alternative resilience strategies. The decision framework can be applied to municipalities within the 18 coastal states of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico.

Literature Review

Voluntary Buyout Programs Funded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency

Voluntary buyout programs are an effective flood mitigation strategy as they are economically feasible and provide a permanent solution to flooding risks. These programs facilitate the removal of at-risk structures from floodplains and enable people to relocate and move out of flood-prone regions voluntarily. Once property owners agree to sell, the residents are relocated, and the local government may use the land for open space activities to restore floodplain functions (Mach et al., 2019).

Voluntary buyout programs are primarily funded by FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, but other Hazard Mitigation Assistance (HMA) programs (i.e., Flood Mitigation Assistance Program [FMA] and Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities [BRIC]) fund property acquisition projects as well (Peterson et al., 20208). Voluntary buyout programs usually receive funding for up to 75% of project costs from FEMA, but exceptions exist where FEMA may cover a higher cost-share, such as 90% for small, impoverished communities (i.e., those with 3,000 or fewer residents and an average income below 80% of the national per capita income) (Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], 20239).

Voluntary Buyout Programs and Systematic Equity Framework

Local governments often decide who can receive a purchase offer. Because these decisions play a critical role in shaping the social composition of the community (Siders, 2019), the selection and prioritization of properties for acquisition are among the most challenging tasks for local decision-makers (FEMA, 199810). Practitioners may prioritize specific properties depending on the local context and the community’s overall environmental, social, economic management, and resilience goals. For instance, they might select properties that have been flooded in the past, are located in the floodplain, are expected to be substantially damaged in the future, do not have flood insurance, or meet multiple criteria. In most cases, the program administrator’s personal sense of what is effective and fair tends to be the main factor influencing how they decide how many and which properties to select for buyouts (Siders & Gerber-Chavez, 2021). The ad hoc and subjective decision-making for selecting and prioritizing buyout program participants leads to concerns about the program’s potential to undermine systematic equity. Systematic equity in flood mitigation planning is achieved when distributive, procedural, and recognitional equities are considered (Bozeman et al., 202211).

Distributive Equity

In the context of flood mitigation planning and implementation, distributive equity ensures federal resources are distributed fairly and unbiasedly to a person, group, or society as a whole (Bozeman et al., 2022; Sovacool et al., 201912). By addressing distributive equity, people across various demographic groups can have full access to resources and opportunities (Markkanen & Anger-Kraavi, 201913; Rawls, 199914).

Procedural Equity

Procedural equity focuses on fair and unbiased decision-making processes while encouraging public participation in making those decisions (Meerow et al., 201915), especially from underrepresented groups (Romero-Lankao & Nobler, 202116). Procedural equity promotes transparency and representativeness.

Recognitional Equity

Recognitional equity entails recognizing different intersecting identities of individuals (e.g., race, gender, and class) and acknowledging that these identities may impact their access to resources, their capacity to participate in decision-making processes, and their ability to withstand or recover from floods (Meerow et al., 2019).

Research has shown that buyout programs may cause financial constraints for parties involved, especially renters (Dundon & Camp, 202117). Participation benefits and consequences can vary based on housing tenure status (i.e., the type of ownership of occupancy arrangement with one’s residence). Unlike owners, renters have a lower capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist, and recover from disasters due to physical, social, economic, and demographic factors (Lee & Van Zandt, 201918). For example, economic factors contribute to the renter-owner divide as renters gain relatively lower incomes. One study shows that 46% of renters in Galveston, TX faced housing affordability challenges three years before Hurricane Ike because they were paying more than 30% of their income for rent (Hamideh & Rongerude, 201819).

Given the higher social vulnerability of renters to floods, where to implement buyout programs has equity implications. Although participation in HMA-funded projects is usually voluntary for homeowners, this is often not the case for others. Residential and business tenants, as well as owners of mobile homes, are required to evacuate the property/land if the owner agrees to participate in the program (FEMA, 2023). Such mandatory requirements undermine procedural equity, as not everyone can take part in decisions that impact their livelihood.

An Overview of Decision Frameworks

A decision framework is a structured approach for organizing information to facilitate decision-making processes, especially those with an ad hoc nature (Tonn et al., 200020; Wyant et al., 199521). Frameworks provide a set of variables and components for planning, monitoring, evaluating, and researching a complex topic (McDermott et al., 201322). By establishing clear goals and addressing key decision questions, decision frameworks assist decision-makers to proceed from information to choices that inform outcomes (National Research Council, 201323).

In the context of voluntary buyout programs, developing a decision framework can ensure that the selection and prioritization of households for program participation are based on transparent criteria and considerations, ultimately leading to improved outcomes for participants.

Research Question

The main research question of this study is: How can local practitioners evaluate potential equity considerations of using federal grants for voluntary buyout programs?

Research Design

To answer the study’s research question, we developed a decision framework to support local government practitioners in identifying residential properties for the buyout program and evaluate the potential equity implications of their selection. We developed this framework by conducting a review of literature and policy documents and interviewing experts in local and state government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and academia. We tested the decision framework by applying it to the City of Galveston, TX, using the IN-CORE modeling software.

Document Review

We conducted a systematic document review of academic research articles and policy documents, identified through platforms such as Google Scholar and Google Search Engine. Using these platforms, we limited our search to the years between 1990 to 2024 and used a combination of the following keywords to find articles and policy documents: “buyout program,” “property acquisition,” “managed retreat,” “relocation,” “equity,” and “hazard mitigation assistance”. Once a number of relevant documents were identified, we employed snowball sampling—using the reference list of the reviewed articles—to find additional articles and reports. After carefully reviewing the resulting documents, we found 48 articles and policy documents relevant to our study. We synthesized our findings into a structured literature review matrix. This matrix contained key insights from the reviewed documents, including the studies’ utilized methodologies, variables (where applicable), any equity considerations associated with participating in or administering the buyout programs, challenges for administering the buyout programs, and points of intervention for improving the buyout programs.

Interviews

In addition to the review of literature and policy documents, we conducted semi-structured interviews with three groups of participants:

- Local government practitioners with expertise in voluntary buyout programs were interviewed because they are directly involved in applying for funding and implementing buyouts at the community-level. Their insights were crucial for understanding the practical challenges and considerations involved in participant selection, as well as how local context influences decision-making processes. The practitioners were based in different coastal municipalities and counties across the United States.

- State government practitioners in charge of voluntary buyout programs were interviewed to provide a broader perspective on how state-level policies shape the implementation of buyouts. Their insights were especially valuable for identifying selection criteria for buyout programs funded through non-federal sources. The interviewed practitioners were based on different coastal states across the United States.

- Experts in nonprofit organizations and academia were interviewed to offer an external, research-based perspective on voluntary buyout programs. Their experience working directly with diverse groups and communities offered valuable insights into the on-the-ground realities and needs of participants.

We identified potential interviewees through a combination of Google searches using specific keywords related to voluntary buyout programs, and referrals provided by colleagues and experts in the field, who recommended individuals with relevant expertise. To ensure a structured approach in data collection, we developed an interview guide that encompassed questions on three topics: the process of applying for funding for buyout programs; decisive factors for selecting and prioritizing households for program participation, and; long-term evaluation and success of buyout programs. Overall, we interviewed 10 experts. The interviews were conducted via Zoom and lasted approximately 60 minutes each. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using the Atlas.ti (Version 25.0.1) qualitative data analysis software.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

Our research was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Stony Brook University, NY, with the approval date of February 2024. For the interviews, we recruited local practitioners from lower-capacity coastal municipalities to ensure their valuable insights were included and unique conditions of their communities are captured. Moreover, we ensured interviews were scheduled at convenient times for participants and maintained their confidentiality and anonymity throughout the process.

The Voluntary Buyout Program Decision Framework

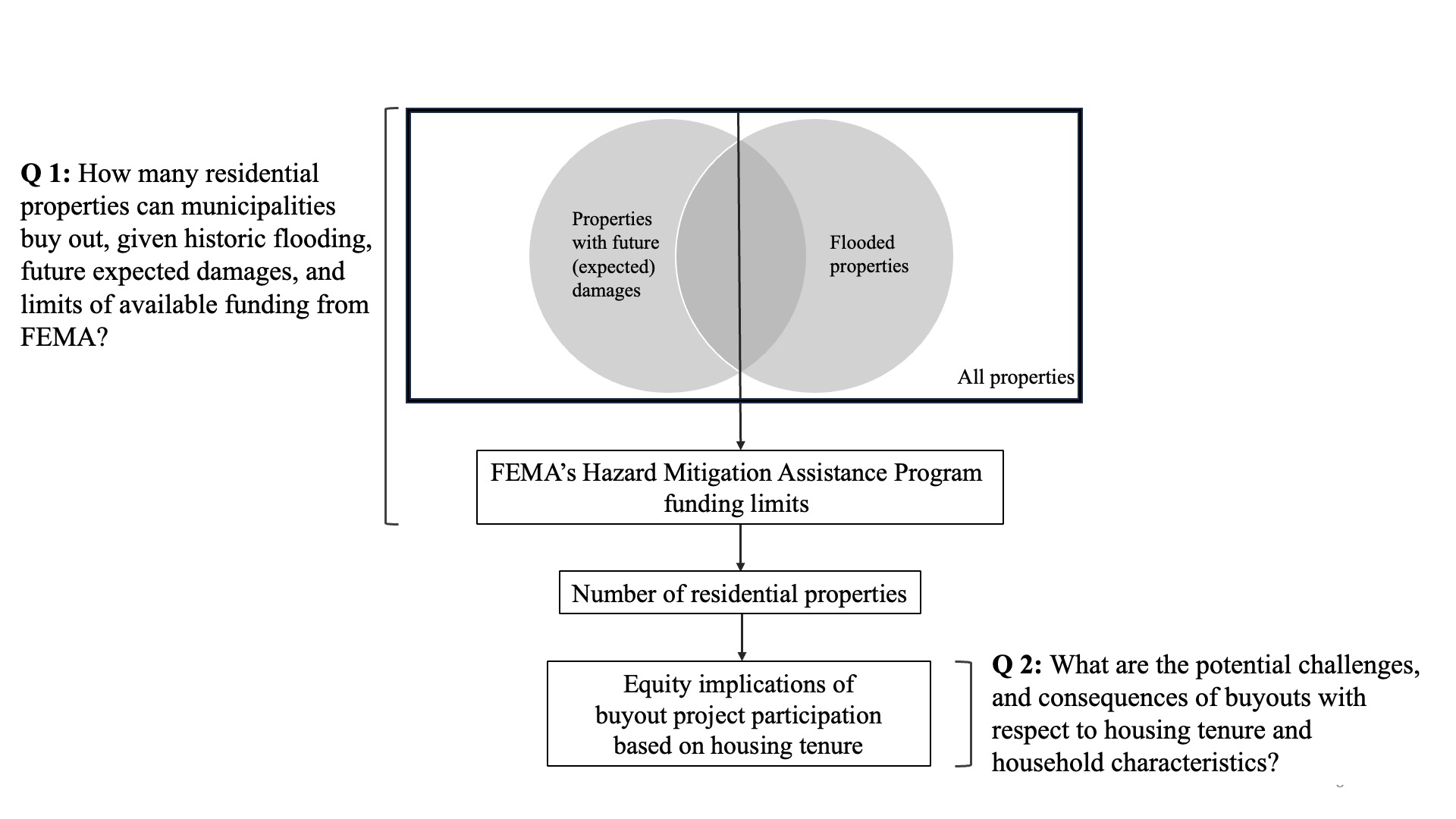

Figure 1 shows the decision framework diagram. As outlined in the subsection “An Overview of Decision Frameworks,” identifying key decision questions is crucial for developing the decision framework and to enhance clarity and transparency in decision-making processes. Therefore, two decision questions are the basis of this framework:

- How many residential properties can municipalities buy out, given three criteria of historic flooding, future expected damages, and limits of available funding from FEMA?

- What are the potential challenges, and consequences of buyouts with respect to housing tenure and household characteristics?

Figure 1. The Decision Framework Diagram

Initially, the decision questions were informed by identified gaps in the literature, then were verified through the interviews with local and state government experts to ensure they addressed community needs. The first criterion outlined in decision question 1 emphasizes the importance of considering past events for identifying candidate properties and households for program participation, as relocation decisions are often derived by severe flooding and damages following a disaster (Hotard & Ross, 202324; Siders, 2019). Yet, it is also necessary to consider and combine past analysis with prediction to inform adaptation strategies (Nelson & Camp, 202025), as highlighted in the second criterion of decision question 1. Proactive disaster planning, while understanding how future hazards could unfold, provides a unique opportunity to assess the potential flaws in adaptation strategies and their social impacts. For the last criterion in decision question 1, it is important to ensure that the value of candidate properties for buyouts are realistic and consistent with FEMA’s previously funded buyout projects. This approach guarantees that the selected properties reflect real-world financial constraints.

Study Site and Access

The City of Galveston is a barrier Island located in southeast Texas within the Galveston County. Galveston is home to a racially and ethnically diverse population. As of 2020, the City’s population of 53,695 residents includes approximately 55% non-Hispanic White, 17% non-Hispanic Black, and 29% Hispanic or Latino individuals (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.26).

Besides the City’s diverse population characteristics, we selected Galveston for applying the proposed decision framework due to its extensive hazard history and high exposure to coastal hazards. Since 2000, Galveston County has experienced 17 federal disaster declarations, highlighting the limitations of local response and recovery capabilities in the face of these frequent and severe events (FEMA, 2024a27).

Addressing Decision Question 1: Galveston Case Study

To address the first decision question and apply the framework to the City of Galveston, we leveraged a research-based decision-support platform called IN-CORE (Center of Excellence for Risk-Based Community Resilience Planning, 202428). IN-CORE is open-source modeling software that estimates the impacts of natural hazards on a community, assesses community disaster resilience, and supports policies and decisions to advance community resilience goals. The platform incorporates a risk-informed approach to decision-making that enables quantitative comparisons of alternative resilience strategies.

We first utilized IN-CORE’s building inventory of 29,541 residential and non-residential structures across the island (Nofal et al., 202329). Next, to identify candidate properties that have been flooded in the past and are projected to be destroyed due to a hurricane event in the future, we used IN-CORE’s building damage model. The building damage model was developed from fragility analysis to estimate the probability of damage resulting from hurricanes including surge, wind, and waves, based on the building attributes and occupancy status (Nofal et al., 2023). After removing the non-residential buildings, we utilized the hindcast model of Hurricane Ike’s water level and wave conditions to identify residential buildings destroyed in the past. Then, to select properties predicted to be destroyed due to a future event, we used the future hurricane scenario with 100-year return period.

To ensure that the value of identified properties was realistic and aligned with FEMA’s HMA financial limitations, the framework utilized the OpenFEMA's HMA Mitigated Properties Dataset (FEMA, 2024b30) to compare property values with the maximum amount paid to the property owners for buyout participation. We used Python Programming Language to filter the original HMA Mitigated Properties Dataset and included 18 coastal states of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico from 2000 to 2020.We excluded potential data entry errors and obtained entries labeled as acquisition/demolition. Moreover, the amounts paid to homeowners were adjusted for inflation, using 2020 as the base year. To answer the first decision question, we excluded any residential properties with appraised value above $321,292, which is the maximum funding amount allocated to homeowners for acquiring properties within the State of Texas.

Addressing Decision Question 2: Galveston Case Study

To answer the second decision question with application to the City of Galveston, we used IN-CORE’s Housing Unit Allocation (HUA) model to determine the selected household characteristics and tenure status, necessary for understanding the equity implications of buyout participation. The goal of this model was to connect social units (e.g., individuals and households) to infrastructure systems using probabilistic allocation model (Rosenheim et al., 202131). The Housing Unit Allocation model linked housing unit characteristics (e.g., size and vacancy status) to household characteristics (e.g., race and income) utilizing the 2010 Census Bureau's socioeconomic and demographic data.

After identifying the potential buyout program participant’s tenure status, we used the data collected through the semi-structured interviews and the literature review matrix to discuss the potential equity implications of participating in the buyout programs using three dimensions of systematic equity (i.e., distributive, procedural, and recognitional).

Findings

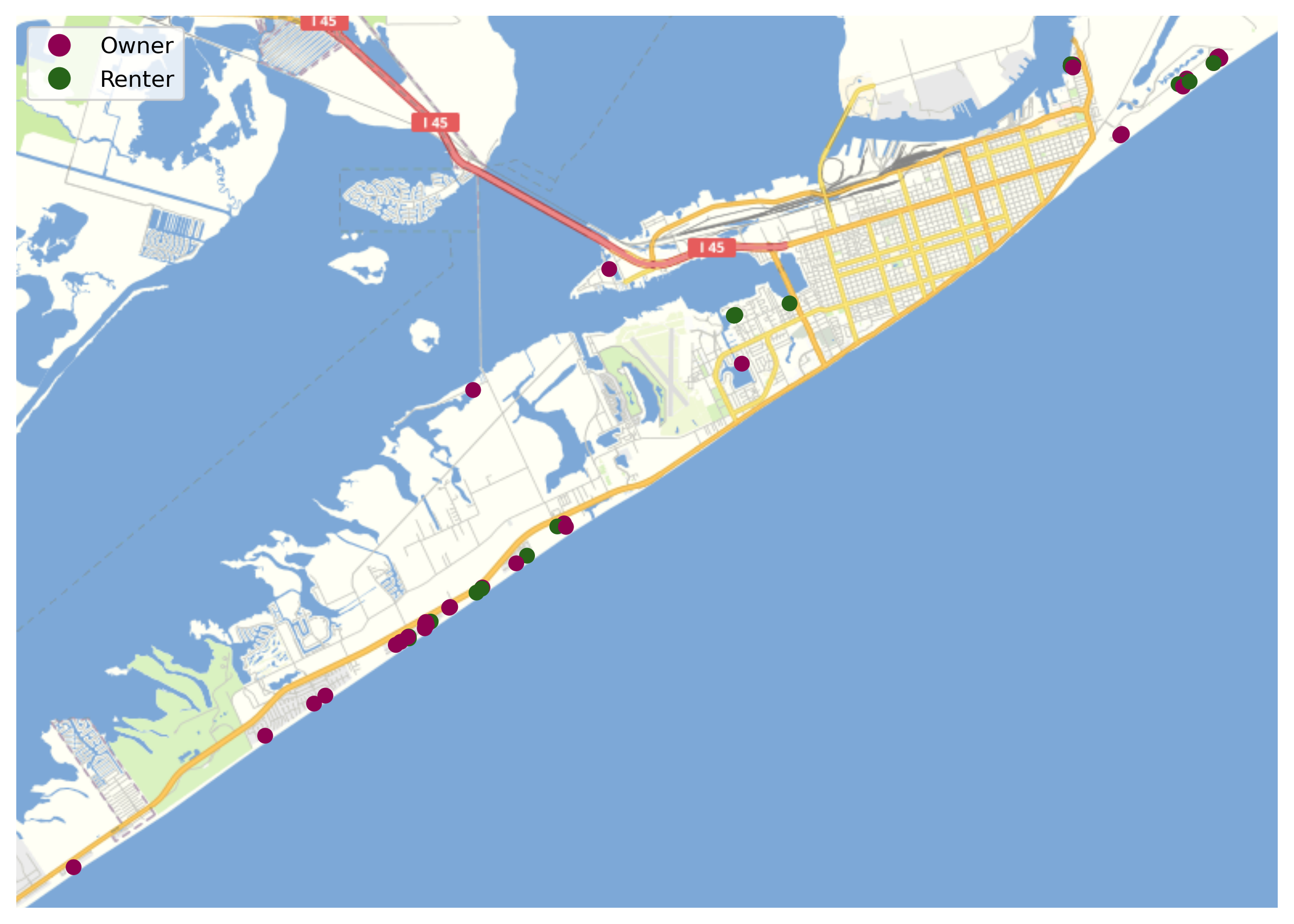

The preliminary findings in this section are based on applying the decision framework to the City of Galveston. Out of 29,541 buildings in Galveston, we selected 52 candidate occupied residential buildings that met our defined three criteria for buyout selection (i.e., historic flooding, future expected damages, and limits of available funding from FEMA). The 52 selected buildings contained 68 housing units, occupied by 44 homeowner households and 24 renter households. The location of buyout candidate buildings in Galveston according to the household tenure status is shown in Figure 2. This figure highlights that most of the candidate properties for buyouts are near Galveston’s southern shore, indicating the area's high exposure to both past and future hazards.

Figure 2. Location of Candidate Properties for Buyout by Tenure Status

Table 1 shows the summary of potential challenges that inhibits households from participating in the buyout program and potential consequences that they face after participation in the buyout program. We categorized the challenges and consequences based on the dimensions of systematic equity (i.e., distributive, procedural, and recognitional). This summary, along with the criteria identified to select candidate properties for buyout programs draw from a comprehensive literature review, policy synthesis on social justice implications of voluntary buyout programs, and insights from ten expert interviews with nonprofit leaders, academics, and government officials. From this work, we identified two key insights: First, there is a clear need for proactive voluntary buyout programs. Second, potential beneficiaries, especially those with tenure status disadvantages, face challenges participating in the program.

Table 1. Equity Implications of Buyout Programs Considering Household’s Tenure Status

| Distributive Equity | Renter households only: Renter-occupied homes are less likely to undergo buyouts Homeowner households only: Homeowners are less likely to participate if they have a mortgage Lower chance of accepting an offer if cost sharing is required |

Renter and homeowner households: Possibility of unaffordable housing options upon relocation Financial constraints Possibility of relocating to areas with high flood exposure and social vulnerability |

| Procedural Equity | Homeowner household only: Program participation depends on financial standing, place-based attachments, risk perception, flood exposure, family composition, and community ties |

Renter and homeowner households: Financial constraints Renter households only: Mandatory relocation |

| Recognitional Equity | Renter household only: Foreign national renters are ineligible for federal relocation benefits and post-buyout assistance, which makes it more challenging for local governments to provide assistance to this group |

Renter and homeowner households: Losing social network if relocated outside their community |

The Need for Proactive Voluntary Buyout Programs

Voluntary buyout programs are mostly reactive, following damages and flooding caused by a recent disaster (criterion 1 in the buyout decision framework), as explained by an expert interviewee:

Residents who are experiencing flooding, particularly repeated flooding, find out that it's possible to get a government financed buyout and then they get their act together, and they go to their local community and say: Hey, we need you to apply for these funds and get us the hell out of here. […] That is often the very first step. It's not the local government proactively going out and saying we would like to help you get somewhere else. It often is the community members organizing themselves and then, having to advocate to their local community to help them.

Though buyout programs are often implemented in reaction to past flooding, we found the importance of considering future predictions to inform adaptation strategies (criterion 2 in the buyout decision framework). One buyout program expert confirmed:

Communities increasingly need to think about what parts of their community are unsafe today and will be increasingly unsafe in the future. As sea levels rise and flood risks increase, we need to identify vulnerable areas and consider what we can do to make them safer 20 or 30 years from now. […] We should start working on that now, not waiting for 50 years. […] We could proactively encourage people to leave and do voluntary buyouts.

A changing climate, more frequent nuisance flooding, sea-level rise, increased high tide flooding, storm surges, and other coastal hazards, combined with development and demographic concentration in coastal regions urgently requires implementing adaptation strategies (Griggs & Reguero, 202132). Proactive planning for buyout programs, while understanding how future hazards could unfold, provides a unique opportunity to assess the potential flaws in adaptation strategies and their social impacts. We found that expert interviewees agree that a decision framework could facilitate proactive planning of buyouts. As one expert noted:

I think a framework like this is actually pretty useful. Most communities aren't doing this proactively in any way, shape or form. It's all reactive. But I think if communities, especially in coastal areas, can look and see: Okay, we've got some areas that are going to be underwater, and they could use a tool like this to prioritize. Where should we start to target our resources? […] I think 50 or 75 years from now, when we look back, the communities that have been most successful and are the most prosperous are going to be the ones that had the courage to actually talk to their residents about these problems decades before the problem arrives.

Similarly, another expert interviewee mentioned:

A tool like this, I think, is an opportunity to try and capture some of the knowledge from the people that you're speaking to, that an individual program manager somewhere who's thinking about buyouts for the first time has no access to talk to that person. But you can capture some of their lessons and sort of integrate it into the tool […] What can be said is: These are the things you need to consider, and these are some things that are often prioritized, and these are the reasons why and why not. I think that kind of thing would be really helpful.

These insights reveal a critical gap in proactive planning for buyout programs, as many communities continue to rely on reactive approaches. Using a structured approach to implement buyout programs can enable practitioners to engage in proactive planning more effectively.

Household Tenure and Challenges of Program Participation

Table 1 highlights the varying participation challenges faced by homeowner and renter households. For example, our review of policy documents shows that while United States citizens can apply for federal government relocation assistance if they participate in buyout programs, non-citizen renter households are inhibited from applying to such benefits. This exclusion not only exacerbates existing inequalities but also imposes additional financial constraints on ineligible households.

Moreover, participation in the program for homeowner households depends on various factors. For instance, households with a mortgage may choose not to participate (Seong et al., 202133) or may not be selected for participation, as noted by one expert interviewee:

[…] In some cases, the state is a pretty good negotiator [to make arrangements with the banks]. […] But, if you're a community that doesn't have the capacity to deal with those kinds of situations, and you're choosing who is gonna get the limited amount of buyout funding you have, you're probably gonna go with the people who don't have this complicated mortgage situation.

Another factor influencing homeowners' decisions to participate is the out-of-pocket expenses they must cover, such as the 25% match requirement for FEMA-funded buyout programs. As one of our expert interviewees from a nonprofit explained:

Federal grants involve a non-federal match. […] Anecdotally, every once in a while, you do hear about homeowners needing to come up with the match. The way that it shakes out typically is, if there's a 25% match requirement, they just get 25% less. Which is obviously a big problem, right? And has really big equity implications. And it's something that I hope that anyone who's administering a buyout program tries to avoid as much as possible.

Though uncommon in most municipalities, one local government practitioner expert from a coastal municipality confirmed that in their jurisdiction, they often pass the cost-sharing burden onto homeowners:

Typically, what happens, at least in our case, is that buyout program or the HMGP [Hazard Mitigation Grant Program] is 75% federal funding and 25% local match. So, the city would not be wanting to come to the table with 25% of the city's money. So, the city has to get the buy in from the homeowner, you know, they're gonna get 25% less than the project cost. But if their property is not any good, if it’s on the beach front, if they don't buy it out, then, you know, they're gonna take a 100% loss. So, most of the time they'd rather get the 75% in their pocket, than lose the whole 100% value of their property.

The findings indicate the importance of considering equity in decision-making processes related to voluntary buyout programs. While experiences of past disasters and anticipated future conditions are key factors in identifying potential participants, it is essential to evaluate who may face challenges if they choose to participate in the program. Insights from interviewees reveal that financial complexities, such as existing mortgages and the capacity of local governments to negotiate favorable terms for households, can create barriers to participation. Additionally, out-of-pocket expenses present another challenge, limiting the participation of households. Even when some households choose to participate despite these costs, they may face challenges in finding comparable housing for relocation due to financial constraints. This highlights the necessity of proactively planning for voluntary buyout programs while considering equity in making decisions.

Conclusions

Implications for Practice or Policy

Local governments often decide who can receive a buyout offer, which makes the selection and prioritization of properties and households among the most challenging tasks of local decision-makers (FEMA, 1998). We addressed this complexity by offering a systematic framework for supporting local practitioners in the equitable use of federal funds for buyouts. This framework simplifies a complex decision-making process by providing a structured approach, making it easier for practitioners—particularly those unfamiliar with buyout programs—to implement the program more equitably. For this purpose, the framework’s steps, Python codes, interactive maps, and implementation details are available for free at https://incore.ncsa.illinois.edu/doc/incore/analyses/buyout_decision.html. This resource enables researchers and practitioners to replicate, recreate, or adapt the framework to align with their resilience goals and priorities.

Limitations

The decision framework does not incorporate two criteria identified by expert interviewees for selecting and prioritizing buyout program participants: whether households have flood insurance policies through the National Flood Insurance Program and whether properties were repeatedly flooded. This limitation is due to privacy concerns, as such detailed information is only publicly available at an approximate location level to protect individual privacy. Consequently, the framework may not fully capture all relevant considerations in prioritizing buyout program participants.

Future Research Directions

Local governments sometimes fail to plan for the use of land acquired through buyouts, leading to missed opportunities for transforming these areas into green open spaces that could alleviate flooding. Future research should incorporate post-buyout land use management into the decision framework to ensure these spaces are utilized strategically and do not become a financial or administrative burden for communities.

References

-

Mach, K. J., Kraan, C. M., Hino, M., Siders, A. R., Johnston, E. M., & Field, C. B. (2019). Managed retreat through voluntary buyouts of flood-prone properties. Science advances, 5(10), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax8995 ↩

-

Mcghee, D. J., Brokopp Binder, S., & Albright, E. A. (2019). First, do no harm: Evaluating the vulnerability reduction of post-disaster home buyout programs. Natural hazards review, 21(1), 05019002. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000337 ↩

-

Sanders, M. (2022, April 1). Property buyouts can be an effective solution for flood-prone communities. Pew Charitable Trusts. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2022/04/property-buyouts-can-be-an-effective-solution-for-flood-prone-communities ↩

-

Siders, A. R. (2019). Social justice implications of US managed retreat buyout programs. Climatic change, 152(2), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2272-5 ↩

-

Siders, A. R., & Gerber-Chavez, L. (2021, August). Floodplain buyouts: Challenges, practices, and lessons learned. Disaster Research Center, University of Delaware. https://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/30164 ↩

-

Weber, A., & Moore, R. (2019). Going under: Long wait times for post-flood buyouts leave homeowners underwater. The Natural Resources Defense Council. https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/going-under-post-flood-buyouts-report.pdf ↩

-

Horn, D. P. (2023). Flood buyouts: Federal funding for property acquisition. Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11911 ↩

-

Peterson, K., Apadula, E., Salvesen, D., Hino, M., Kihslinger, R., & Bendor, T. K. (2020). A review of funding mechanisms for US floodplain buyouts. Sustainability 12(23), Article 10112. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU122310112 ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). (2023). Hazard mitigation assistance program and policy guide. https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/learn/hazard-mitigation-assistance-guidance ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). (1998). Property acquisition handbook for local communities. https://www.fema.gov/pdf/government/grant/resources/hbfullpak.pdf ↩

-

Bozeman, J. F., Nobler, E., & Nock, D. (2022). A path toward systemic equity in life cycle assessment and decision-making: Standardizing sociodemographic data practices. Environmental engineering science, 39(9), 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1089/EES.2021.0375 ↩

-

Sovacool, B. K., Martiskainen, M., Hook, A., & Baker, L. (2019). Decarbonization and its discontents: a critical energy justice perspective on four low-carbon transitions. Climatic change, 155(4), 581–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02521-7 ↩

-

Markkanen, S., & Anger-Kraavi, A. (2019). Social impacts of climate change mitigation policies and their implications for inequality. Climate policy, 19(7), 827–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1596873 ↩

-

Rawls, J. (1999). A theory of justice (Revised ed.). Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Meerow, S., Pajouhesh, P., & Miller, T. R. (2019). Social equity in urban resilience planning. International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 24(9), 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2019.1645103 ↩

-

Romero-Lankao, P., & Nobler, E. (2021). Energy justice: Key concepts and metrics relevant to EERE transportation projects [NREL/MP-5400-80206]. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/80206.pdf ↩

-

Dundon, L. A., & Camp, J. S. (2021). Climate justice and home-buyout programs: Renters as a forgotten population in managed retreat actions. Journal of environmental studies and sciences, 11(3), 420–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-021-00691-4 ↩

-

Lee, J. Y., & Van Zandt, S. (2019). Housing tenure and social vulnerability to disasters: A review of the evidence. Journal of planning literature, 34(2), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412218812080 ↩

-

Hamideh, S., & Rongerude, J. (2018). Social vulnerability and participation in disaster recovery decisions: public housing in Galveston after Hurricane Ike. Natural hazards, 93(3), 1629–1648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3371-3 ↩

-

Tonn, B., English, M., & Travis, C. (2000). A framework for understanding and improving environmental decision making. Journal of environmental planning and management, 43(2), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560010658 ↩

-

Wyant, J. G., Meganck, R. A., & Ham, S. H. (1995). A planning and decision-making framework for ecological restoration. Environmental management, 19(6), 789–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02471932 ↩

-

McDermott, M., Mahanty, S., & Schreckenberg, K. (2013). Examining equity: A multidimensional framework for assessing equity in payments for ecosystem services. Environmental science & policy, 33, 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2012.10.006 ↩

-

National Research Council. (2013). Sustainability for the nation: Resource connections and governance linkages. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13471 ↩

-

Hotard, A. E., & Ross, A. D. (2023). Home buyout without relocation: An examination of dissonant hazard mitigation perceptions among Gulf Coast residents. Risk, hazards & crisis in public policy. https://doi.org/10.1002/RHC3.12284 ↩

-

Nelson, K. S., & Camp, J. (2020). Quantifying the benefits of home buyouts for mitigating flood damages. Anthropocene, 31, Article 100246. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANCENE.2020.100246 ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). Populations and People, Galveston city, Texas, Census Bureau profile. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://data.census.gov/profile/Galveston_city,_Texas?g=160XX00US4828068#populations-and-people ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). (2024a). Disaster declarations for states and counties. https://www.fema.gov/data-visualization/disaster-declarations-states-and-counties ↩

-

Center of Excellence for Risk-Based Community Resilience Planning. (2024). Interdependent networked community resilience modeling environment (IN-CORE). https://incore.ncsa.illinois.edu/ ↩

-

Nofal, O. M., Amini, K., Padgett, J. E., van de Lindt, J. W., Rosenheim, N., Darestani, Y. M., Enderami, A., Sutley, E. J., Hamideh, S., & Duenas-Osorio, L. (2023). Multi-hazard socio-physical resilience assessment of hurricane-induced hazards on coastal communities. Resilient cities and structures, 2(2), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RCNS.2023.07.003 ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). (2024b). Hazard Mitigation Assistance Mitigated Properties. https://www.fema.gov/about/openfema/data-sets#hazard ↩

-

Rosenheim, N., Guidotti, R., Gardoni, P., & Peacock, W. G. (2021). Integration of detailed household and housing unit characteristic data with critical infrastructure for post-hazard resilience modeling. Sustainable and resilient infrastructure, 6(6), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/23789689.2019.1681821 ↩

-

Griggs, G., & Reguero, B. G. (2021). Coastal Adaptation to Climate Change and Sea-Level Rise. Water 13, 13(16), Article 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/W13162151 ↩

-

Seong, K., Losey, C., Zandt, S. Van, Heinzlef, C., Laffrechine, K., & Barroca, B. (2021). To Rebuild or Relocate? Long-Term Mobility Decisions of Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) Recipients. Sustainability 13(16), Article 8754. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU13168754 ↩

Motlagh, F., & Hamideh, S. (2025). A Decision Framework for Equitable Use of Federal Funds in Buyout Programs. (Natural Hazards Center Mitigation Matters Research Report Series, Report 23). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder.