From the Ashes: Mitigation Policy After Wildfire in California

Publication Date: 2022

Abstract

Wildfires that destroy whole communities are increasingly prevalent, yet few studies examine long-term recovery after wildfire. This is a pivotal time when communities can use rebuilding and restoration efforts to enhance fire adaptation measures. Recently, California communities have been impacted by wildfires that are unprecedented in scale. Human communities and ecosystems struggle to recover quickly and in ways that reduce future wildfire vulnerability. In the absence of federal wildfire risk governance standards, interactions between state and local policies are crucial to understanding how communities navigate this challenge. This study was designed to investigate policy and practice barriers to wildfire mitigation in three California communities. We asked stakeholders how recent wildfire experience affected housing recovery programs, land use planning, and requirements for household-level mitigation to explore tensions between post-disaster recovery and mitigation efforts. Despite a handful of local recovery successes, our findings reveal an environment in which wildfire risk reduction can be hindered by conflicts between state and local priorities, environmental concerns, competition among neighboring jurisdictions, and the collective nature of wildfire mitigation strategies.

Introduction

The post-disaster recovery period offers a distinct opportunity to promote wildfire mitigation at household and community levels using formal requirements and voluntary programs (Mockrin et al., 20181; Schumann et al., 20202). For households, this can include the use of fire-resistant building materials or the creation and maintenance of defensible space around structures. Community-level mitigation entails large-scale vegetation management programs that combine one or more strategies such as prescribed burns, mechanical removal, chipping, pile burns, and livestock grazing. Additionally, wildfire risk must be considered in community development, design, and permitting, since both the configuration and extent of development and open space can impact resident safety (Mowery et al., 2019).

Although a toolkit of wildfire mitigation strategies that addresses varying scales of risk is not new, wildfires that destroy whole communities are increasingly prevalent. Research points to a confluence of factors contributing to this trend, including a legacy of fire suppression, increased population growth and development in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), and a warming climate where frequent and prolonged droughts create dangerous fuel conditions (Abatzoglou and Williams, 20163; Radeloff et al., 20184). Given that more communities will face the need to recover from destructive fires, if losses are to be curbed, it is crucial to understand the extent to which affected jurisdictions integrate wildfire risk reduction into planning and regulatory strategies after fire.

Limited research exists on post-wildfire risk reduction and few studies consider the extent or effects of policy changes during recovery. Several studies suggest that state and local officials may inadvertently undermine long-term wildfire risk reduction efforts by championing expeditious housing recovery programs which have goals are at odds with mitigation principles (Mockrin et al., 2018; Paveglio and Edgeley, 20175). Nonprofit organizations, homeowners associations, and emergent citizen groups might also advance or impede progress toward mitigation depending on how they articulate their values and roles in recovery (Goldstein, 20086; Mockrin et al., 20167; Paveglio et al., 20168). While policymakers, practitioners, and community members increasingly recognize the need for coordinated risk governance in ecosystem management and community development (Moritz et al., 20149), the murkiness of how these actors interact and adjust after wildfire sets the stage for the current study.

This study asked how do recent wildfire experiences affect housing recovery programs, land use planning, and requirements for household-level mitigation? Grounding the study in the recent (2015-present) northern California wildfires, we investigated three California sites impacted by repetitive and highly destructive fires (Butte, Lake, and Sonoma Counties). The sites varied in population size and density, proportion of WUI housing, and level of affluence. Recovery is unfolding in these counties against a backdrop of worsening local and state wildfire trends, with record-setting wildfire activity leading to thousands of lost buildings and millions of acres burned. California’s growing wildfire loss profile and the depth of state-level efforts to reduce wildfire risk make the state a singular and worthwhile environment for study.

Methods

Study Sites

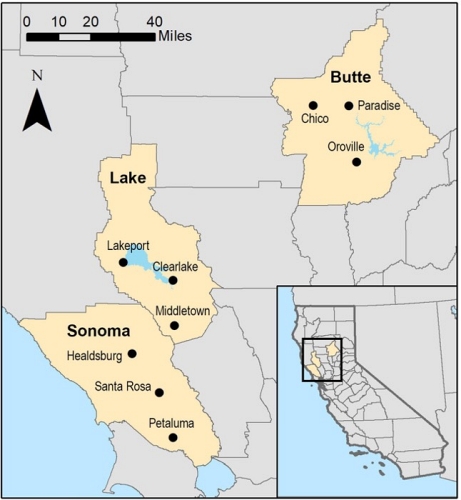

This study focused on Butte, Lake, and Sonoma Counties in northern California (Figure 1), all of which had experienced major destructive fires since 2015 (see Appendix, Table A1). Northern California is an important setting for studying post-fire mitigation and recovery, given its history of wildfires resulting in the loss of homes and lives. Five of the state’s seven largest recorded fires (all of which occurred since 2017) and five of the state’s ten most destructive fires were in this region (California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection [CAL FIRE] 2021a10). These recurrent fires and the chronic risk that fire poses makes the research topic salient for northern California residents and fire professionals.

Figure 1: Map of Study Area Counties and Primary Cities

Long-term recovery is ongoing in all three study communities and complicated by repeated fire events. Each community included a mix of households who relocated, rebuilt without mitigating, and rebuilt with mitigation measures. COVID-19 added another layer of difficulty to recovery by disrupting or slowing access to community services required to design, permit, and build replacement housing. The three communities are currently in different phases of recovery, with rebuilding proceeding most rapidly throughout Sonoma County. In 2021, Paradise, located in Butte County, became the fastest growing city in California (Saam and Matthey, 202111); however, rebuilding in rural areas of Butte County has lagged. Lake County experienced years of fire losses (60% of the county’s land area has burned in the past seven years) and its recovery from fires has been slow (only 25% of homes destroyed in the 2015 Valley fire had been rebuilt three years after the fire) (Hubert, 201812; County of Lake, 201813).

Beyond the variation in recent fire history and recovery statuses, these locations varied across several contextual factors that might have affected the ability or willingness to engage in wildfire prevention and risk reduction activities (see Appendix, Table A1). These factors included differing levels of affluence, housing density and housing needs, proportion of housing located in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), pace of WUI housing growth, and extent of previous wildfire damage (community core vs. periphery). Furthermore, differences in cause of ignition (arson, negligence, lightning), responsibility for fires (personal vs. corporate), and major disaster declaration status impacted the availability of recovery assistance for residents in the three counties. For instance, the first two rounds of financial resources from Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) settlements weren’t disbursed until November 2020 and March 2021) in Sonoma and Butte Counties (Kasler, 202114). Disbursement of federal disaster recovery funds through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) was uneven because of a mixture of factors including inaccessible aid, lack of local capacity to apply for and manage grants, and federal funding ineligibility due to low damage assessment totals.

Participants and Data Collection

We conducted 29 semi-structured interviews with 37 participants, including federal and state officials, wildfire professionals, local officials, and community leaders knowledgeable about ongoing wildfire recovery and/or risk reduction efforts (some interviews included two to three participants). Our original research plan included in-person interviews, tours of neighborhoods affected by wildfire, and local policy document review, however, due to COVID-19 travel restrictions and related logistical challenges, we collected data solely using remote interviews. The unprecedented 2020 fire season significantly also slowed the remote interview process. Early interviews revealed a much wider set of relevant policy documents than anticipated, so we decided to postpone the policy document review. Interviews were conducted via Zoom between July 2020 and October 2021 and lasted approximately one hour each.

Participants included 24 individuals affiliated with Butte, Lake, and Sonoma counties (we refer to these collectively as local participants) and 13 who worked at the state level or in roles that extended beyond our study area (we refer to these as non-local participants in Table 1).To begin data collection, we first interviewed university liaisons and a wildfire consultant who had birds-eye views of state-level policies, programs, and attitudes about wildfire risk, as well as local knowledge on these issues. We then used purposive, respondent-driven sampling to recruit state and federal officials to learn more about policy and practice priorities for wildfire recovery and mitigation. Next, we reached out to local stakeholders who could discuss the status of wildfire recovery and/or mitigation actions in their county. Local interviewees included city and county government officials in charge of recovery, land use planning, permitting, building, and code enforcement. They also included community leaders from nonprofit organizations; informal or emergent groups, such as neighborhood collaboratives; and citizen councils and elected bodies. In terms of gender demographics, participants were comprised of 17 males and 20 females.

Table 1: Participant Sample by Interviewee Role, and Location

| Interviewee Role | ||||

| University Liaison | ||||

| Wildfire Consultant | ||||

| Federal Government | ||||

| State Government | ||||

| Local Government | ||||

| Community Leader | ||||

| Totals |

The questions posed during the interviews revolved around agency/organization priorities in wildfire recovery and/or risk reduction, status and success of current efforts, policies or strategies proposed but not implemented, challenges in meeting recovery and mitigation goals, and the future of wildfire risk in the region. Interviews with non-local participants focused on state and federal policy agendas, while local interviews focused more on the implementation of these policies. Additionally, local interviewees were asked about their county’s wildfire history and to characterize losses from previous fires. For both groups, we continued to conduct interviews until theme saturation was reached.

Data Analysis

Interview data were first recorded, transcribed, and deidentified with the help of two research assistants. The research team reviewed non-local interviews first and conducted open coding to inductively identify themes. Team members took turns organizing these theme codes hierarchically into umbrella codes until a consensus was reached. Next, the team repeated this process with local interviews to identify contextual issues unique to each county. Ultimately, most themes transcended study sites, yet interviewees in each county tended to frame these issues in slightly different ways.

Preliminary Findings: Cross-cutting Local Themes

Several themes identified in local interviews cut across counties. These included concerns related to housing, vegetation management, and economic development. In the wake of recent fires, all three counties struggled to provide housing that is safe, sustainable, and affordable. Home hardening to prevent ember entry and structure ignition was seen as a key strategy in making the region’s housing more fire adapted, yet there was disagreement among participants over how to best facilitate these efforts, especially when it comes to retrofitting older housing stock unaffected by recent fires. Cost was also a significant concern, as all three counties were experiencing a housing shortage before this round of fires. Replacement housing—particularly replacement housing that incorporates fire-safe design features (e.g., fine mesh soffit vents, concrete composite roofing, noncombustible cladding and decking)—often exceeds the financial means of local residents.

In terms of vegetation management, there is growing acceptability of fuel treatments—especially prescribed fire—as necessary to reduce future wildfire risk, but all counties encountered difficulties in scaling these efforts to meet the challenge. Factors that limited sustainable, large-scale vegetation management efforts included state-level conservation policies such as the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) Review (1970, rev. 1983)15 that can slow projects, penalties or lack of fiscal incentives for landowners, high degrees of second/vacation home ownership, fragmented land ownership patternsEndnote 1, and parcels inaccessible due to rugged terrainEndnote 2. The mixture of stakeholders (public vs. nonprofit entities) engaging in vegetation management varied between the three counties.

Finally, economic development emerged as a universal theme, but it was threaded differently through discussions of housing and vegetation maintenance in each county. In Butte County, this discussion revolved around creating an economic use for biomass and facilitating agritourism as a way to grow the economy while maintaining park lands as defensible space. In Lake County, this theme focused on allocating new cannabis revenues for wildfire risk reduction projects while growing the tax base through a proposed luxury residential development project (with fire-adapted design features) located in the WUI. In Sonoma County, discussion of economic development was subsumed by discussions of affordable housing and rapid, creative rebuilding efforts (e.g., accessory dwelling units) to restore the pre-fire residential tax base.

Preliminary Findings by County

Butte County

Given the Camp Fire’s catastrophic impacts to Paradise, California, in 2018, it is perhaps unsurprising that discussions related to sense of place were most pronounced in Butte County interviews. Participants indicated that residents who lost their homes wanted to return to their community and rebuild housing similar to what was lost. These hopes were thwarted in many cases, however, by the daunting expense and logistical challenges of rebuilding. Participants described strong attachments to the area’s dense ponderosa pine forests, which are reflected in booster organization logos and citizen preferences for replanting efforts. Yet these are the same forests that fueled the destructive Camp Fire. Given that the Sierra Nevada foothills are transitioning to a warmer, drier climate, several participants questioned the wisdom of replanting forests in the same way instead of allowing a natural conversion to mixed oak woodland and grassland mosaic. In the long run, well managed oak woodlands would be more fire adapted and promote better defensible space in and around developed areas, although they would also disrupt residents’ sense of place. Notably, local agencies and community organizations are leveraging residents’ affinity for forests and recreational lands to further conversations about land use planning as a wildfire mitigation tool. The town of Paradise, in particular, is attempting to assemble a roughly continuous town-level buffer that will act as defensible space for future wildfire response and prevention.

Lake County

In Lake County, participant interviews reflected challenges underlying local government capacity, which shaped the nature of their wildfire recovery and mitigation work. In the wake of the 2015 Valley Fire, repeated disasters (the 2016 Clayton Fire, the 2017 Sulphur Fire, and two additional floods)—which were significant but did not reach the level of federally declared disasters—meant that county offices remained in crisis mode without the capacity to pursue clear priorities related to long-term recovery or mitigation. High employee turnover attributed to burnout and a local culture that community leaders described as leery of government intervention further complicated the county’s ability to be proactive in supporting mitigation efforts. In response, a complex system of hyperlocal community-based organizations (e.g., citizen councils, conservation organizations, tribal entities, and indigenous cooperatives) emerged to meet various community needs that have arisen since the Valley Fire. These organizations are led by either working or retired professionals (including many newcomers) who are repurposing their skills for community service. Although these community-based organizations and nonprofit entities garner trust and confidence among residents, they face a number of challenges in carrying out recovery and mitigation work. Challenges include inadequate staffing, training, and established fiscal mechanisms to effectively pursue and manage external grant funding.

Sonoma County

Relative to the other counties, Sonoma County had more capacity to streamline recovery operations after the 2017 Tubbs Fire and was able to facilitate numerous mitigation projects at multiple scales during the long-term recovery period. A more affluent and larger tax base may partially explain the increased capacity. Interviewees emphasized Sonoma’s adaptability in two respects. First, city and county offices adapted their recovery operations to streamline the rebuilding process for residents affected by the 2017 fires. This included outsourcing permitting functions to handle excess volume and making city departments visible to residents through frequent community meetings. High levels of trust between elected leaders and city and county staff also helped streamline operations. Staff were given significant leeway to make changes to permitting and planning processes that improved efficiency, as long as they maintained communication with elected leaders. Second, the county made its approach to mitigation more proactive. The county’s ability to secure funding through FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program allowed it to take an active role in research that examines the effectiveness of vegetation management strategies in different ecosystems. Sonoma County also invested heavily in public education through a state-funded program called Wildfire Adapted Sonoma that offered property owners free assessments and tailored recommendations to help harden their homes and create defensible space. Despite these adaptations, some participants still identified barriers to actualizing an expeditious and fire-adapted recovery. Barriers arose when contending with multiple hazards (e.g., wildfire and geohazard risksEndnote 3) or when faced with costly infrastructure upgrades (e.g., road widening, drainage improvements, septic/sewer conversion) to comply with safety requirements.

Discussion

Our interviews revealed four overarching themes central to understanding the post-fire environment: (1) conflicts between state and local priorities and perspectives, (2) environmental concerns that delay post-fire recovery and mitigation actions, (3) competition for resources among neighboring jurisdictions, and (4) challenges in fostering collective action to reduce wildfire losses. While these themes are distinct, they are not mutually exclusive. Reflective of the broader hazards literature on post-disaster policy making (Birkland, 199816; Kingdon, 198417), two of these themes (1 and 3) show evidence of tension between post-disaster recovery and mitigation efforts. We briefly explore each theme below, discussing the extent to which state-level perspectives on recovery and mitigation intersected with the local context in our study sites.

First, we often observed conflicts between state and local priorities and perspectives. Both groups acknowledge that managing fires is a shared responsibility, and that wildfire risk reduction must be a priority. Differences were evident, however, in strategies for meeting mitigation goals and balancing mitigation efforts with basic community needs. For example, given that narrow, unpaved roads with untreated vegetation can hinder evacuation efforts and limit the ability of authorities to respond to fires, participants at state and local levels identified impassable roads as a common concern. Yet, while participants at the state level viewed widening roads as high priority, local participants described road widening as impractical given the high (often privately incurred) costs such efforts would require. Likewise, several conflicts between state and local perspectives arose at the intersection of housing and mitigation. Consistent with previous case studies (Mockrin et al. 2018; Paveglio and Edgeley 2017), participants noted a tension between resident desires to rapidly return (even with improvised housing) versus long-term goals to ensure houses were built with fire-resistant materials and that adjacent vegetation would be maintained to fire-safe standards. Efforts to update state building codes to reflect best mitigation practices clashed with a perceived need at the local level to rebuild quickly and affordably. Finally, the ability of local governments to meet Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) targets was at odds with the goal of preventing new housing development in the WUI. Local interviewees noted difficulties in satisfying multiple state-level directives at once. They tended to view the latter aim as counterproductive to economic growth.

A second theme focused on post-fire environmental concerns, where communities struggled to balance requirements set forth in state-level policies (e.g., CEQA) with their desire for an expedient recovery effort. For example, local participants reported needing to pause rebuilding efforts to address water contamination, disposal of dead trees, or other issues as required by state-level policies. Similarly, from a mitigation standpoint, the multiple layers of environmental review prescribed by CEQA and federal regulations added significant time and intricacy to executing large-scale, minimally invasive fuel treatments.

Third, given the scale of recent fires in California, local participants noted that nearby jurisdictions were competing for resources, thus negatively impacting their own post-fire recovery and mitigation. Competition for fire suppression capabilities and rebuilding resources were frequently mentioned. In each of our study counties, ongoing affordable housing shortages were complicated by regional wildfire housing losses. All else being equal, shared problems such as housing scarcity or fire risk can create opportunities for coordination across affected areas. In Butte and Lake Counties, however, low levels of affluence and capacity may have contributed to interviewees’ emphasis on competition for finite recovery resources. These two counties saw themselves at a comparative disadvantage to Sonoma County where residents’ financial assets helped garner adequate resources (e.g., building materials and contractors) to facilitate housing development and rebuilding. Certain aspects of this situation resemble but do not perfectly match the “recovery machine” model of post-disaster community change (Pais and Elliott, 200818). Additionally, Sonoma County’s established infrastructure (e.g., water and sewer systems) expedited rapid reconstruction, whereas reliance on well water and septic tanks complicated and lengthened rebuilding for many Butte and Lake County residents. Recovery studies following hurricanes similarly underscore the influence of critical infrastructure on the location and pace of rebuilding (Reddy, 200019; Cutter et al., 201420; Yabe et al., 202121).

Finally, there was a keen awareness that wildfire risk reduction poses collective action problems requiring broad buy-in from a diverse set of stakeholders. Like floods or other hazards, wildfires do not respect jurisdictional boundaries, so decisions made by neighboring communities affect wildfire exposure for the surrounding area. Efforts to mitigate wildfire risk, however, require a commitment to collective action that is often beyond what is required for other hazards. For example, an individual can elevate their home to reduce their exposure to flooding, but cannot effectively reduce their wildfire exposure without their neighbors also taking steps to mitigation risk on their properties. While previous research on a variety of hazards frequently cites stakeholder collaboration as an inhibitor of community-wide mitigation (e.g., Boda and Jerneck, 201922; Thaler and Seebauer, 201923; Charnley et al., 202024), the degree of cooperation and collective action required at very fine scales (i.e., between individuals and households) required to effectively reduce wildfire risk makes the process of mitigating this hazard especially vexing.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides insights on barriers to wildfire mitigation in California, there are a few limitations and areas for future research worth highlighting. First, this study explored a specific hazard in a particular context, limiting the transferability of its findings. Future studies could replicate this study and triangulate with other methods to see if findings apply in different settings. Second, given the history of wildfire in the area, asking about changes due to recent wildfires was often identified by participants as the “wrong question”. As seen in studies of other hazards (Olshansky et al., 201225), changes were the culmination of a history of wildfire exposure and experience. Future studies could explore how varying levels of community experience with a given hazard shapes policy response. Third, while this study noted issues with funding and governmental capacity in recovery and mitigation, we struggled to acquire federal interviewees. Future research should make it a priority to include federal representatives to better understand their funding priorities, interactions with local and state stakeholders, and their expectations for local capacity. Fourth, this study solely focused on policymakers. Future studies could explore household-level decisions about reconstruction in this post-fire environment. Finally, although our interviews revealed differences in social vulnerability across the communities, the positionalities of our interviewees did not match those of the most vulnerable residents. Without this balance of perspectives, it is premature to draw conclusions about the role of social vulnerability in the experiences and outcomes we observed. Future studies could use a mixture of exploratory qualitative methods and confirmatory surveys to research the post-fire journeys of residents from vulnerable subgroups.

Conclusion

This project investigated how recent wildfire experiences affected housing recovery programming, land use planning, and requirements for household-level mitigation in three Northern California communities. Although the communities varied in population size and density, level of affluence, and fire history, we found several cross-cutting themes, including concerns about providing adequate safe, sustainable, and affordable housing, vegetation management, and economic development. Tradeoffs in balancing these goals were common. We also found evidence of tension between post-disaster recovery and mitigation efforts, which manifested as conflicts between state and local actors on priorities in recovery and mitigation, as well as competition between jurisdictions for limited post-fire resources. Finally, while we found many similarities to recovery and mitigation processes in other hazard contexts (e.g., floods, hurricanes), our findings suggest that the high degree of coordination required at very fine scales may distinguish wildfire from other hazards. This study sets the stage for future research, including exploration of resident decision-making processes in housing recovery, systematic analysis of wildfire mitigation and recovery policy, and evaluation of post-fire mitigation programs that intend to reduce wildfire vulnerability. Findings from this and subsequent studies can help to design policies that better address local stakeholder concerns following fire and incentivize rebuilding practices that ultimately reduce hazard exposure.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Johanna Ostling and Cara Caruolo, who served as research assistants for the project.

Endnotes

Endnote 1: Two patterns of fragmented land ownership inhibited large-scale vegetation management: instances where multiple private landowners owned small parcels adjacent to each other and instances where private land abutted public land. In the latter case, interviewees most often identified federal lands as problematic.↩

Endnote 2: So-called “paper lots,” parcels platted without regard for underlying topography, were identified as contributing to this problem in Lake and Butte County.↩

Endnote 3: We learned of a handful of homeowners were located in designated geohazard zones where the amount of observed ground movement was considered too great for the county to permit post-fire reconstruction.↩

References

-

Mockrin, M. H., Fishler, H. K., & Stewart, S. I. (2018). Does wildfire open a policy window? Local government and community adaptation after fire in the United States. Environmental Management, 62(2), 210-228. ↩

-

Schumann, R. L., III, Mockrin, M., Syphard, A. D., Whittaker, J., Price, O., Gaither, C. J., Emrich, C. T., & Butsic, V. (2020). Wildfire recovery as a “hot moment” for creating fire-adapted communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 42, 101354. ↩

-

Abatzoglou, J. T., & Williams, A. P. (2016). Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(42), 11770-11775. ↩

-

Radeloff, V. C., Helmers, D. P., Kramer, H. A., Mockrin, M. H., Alexandre, P. M., Bar-Massada, A., Butsic, V., Hawbaker, T. J., Martinuzzi, S., Syphard, A. D., & Stewart, S. I. (2018). Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(13), 3314-3319. ↩

-

Paveglio, T., & Edgeley, C. (2017). Community diversity and hazard events: understanding the evolution of local approaches to wildfire. Natural Hazards, 87(2), 1083-1108. ↩

-

Goldstein, B. E. (2008). Skunkworks in the embers of the cedar fire: enhancing resilience in the aftermath of disaster. Human Ecology, 36(1), 15-28. ↩

-

Mockrin, M. H., Stewart, S. I., Radeloff, V. C., & Hammer, R. B. (2016). Recovery and adaptation after wildfire on the Colorado Front Range (2010–12). International Journal of Wildland Fire, 25(11), 1144-1155. ↩

-

Paveglio, T. B., Abrams, J., & Ellison, A. (2016). Developing fire adapted communities: The importance of interactions among elements of local context. Society & natural resources, 29(10), 1246-1261. ↩

-

Moritz, M. A., Batllori, E., Bradstock, R. A., Gill, A. M., Handmer, J., Hessburg, P. F., Leonard, J., McCaffery, S., Odion, D. C., Schoennagel, T., & Syphard, A. D. (2014). Learning to coexist with wildfire. Nature, 515(7525), 58-66. Mowery, M., Read, A., Johnston, K., & Wafaie, T. (2019). Planning the wildland-urban interface (PAS Report 594). American Planning Association. https://www.planning.org/publications/report/9174069/ ↩

-

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. (2021a). Stats and Events. https://www.fire.ca.gov/stats-events/ ↩

-

Saam, K., & Matthey, R. (2021). Paradise is fastest growing city in California, according to new data. KRCR TV News. https://krcrtv.com/news/local/paradise-is-the-fastest-growing-city-in-california ↩

-

Hubert, C. (2018, August 4). Rising from the ashes: It can be long, painful road back – Cobb Mountain family’s rebuild offers idea of what to expect. Sacramento Bee, p. 1A. ↩

-

County of Lake, California. (2018). Long-Term Recovery Priorities. http://www.lakecountyca.gov/Government/Directory/Administration/Visioning/Challenges.htm ↩

-

Kasler, D. (2021, March 15). Wildfire victims to get ‘hundreds of millions’ in PG&E payments. Sacramento Bee, p. 3A. ↩

-

California Environmental Quality Act of 1970. (1970 & rev. 1983). 14 California Code of Regulations §15000 et seq. ↩

-

Birkland, T. A. (1998). Focusing events, mobilization, and agenda setting. Journal of public policy, 18(1), 53-74. ↩

-

Kingdon, J. W., & Stano, E. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (Vol. 45, pp. 165-169). Boston: Little, Brown. ↩

-

Pais, J. F., & Elliott, J. R. (2008). Places as recovery machines: Vulnerability and neighborhood change after major hurricanes. Social forces, 86(4), 1415-1453. ↩

-

Reddy, S. D. (2000). Factors influencing the incorporation of hazard mitigation during recovery from disaster. Natural Hazards, 22(2), 185-201. ↩

-

Cutter, S. L., Emrich, C. T., Mitchell, J. T., Piegorsch, W. W., Smith, M. M., & Weber, L. (2014). Hurricane Katrina and the forgotten coast of Mississippi. Cambridge University Press. ↩

-

Yabe, T., Rao, P. S. C., and Ukkusuri, S. V. (2021). Regional differences in resilience of social and physical systems: Case study of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 48(5), 1042-1057. ↩

-

Boda, C. S., & Jerneck, A. (2019). Enabling local adaptation to climate change: towards collective action in Flagler Beach, Florida, USA. Climatic Change, 157(3), 631-649. ↩

-

Thaler, T., & Seebauer, S. (2019). Bottom‑up citizen initiatives in natural hazard management: Why they appear and what they can do?. Environmental Science & Policy, 94, 101-111. ↩

-

Charnley, S., Kelly, E. C., & Fischer, A. P. (2020). Fostering collective action to reduce wildfire risk across property boundaries in the American West. Environmental Research Letters, 15(2), 025007. ↩

-

Olshansky, R. B., Hopkins, L. D., & Johnson, L. A. (2012). Disaster and recovery: Processes compressed in time. Natural Hazards Review, 13(3), 173-178. ↩

Schumann, R., Mockrin, M. H., Brokopp Binder, S., & Greer, A. (2022). From the Ashes: Mitigation Policy After Wildfire in California (Natural Hazards Center Mitigation Matters Research Report Series, Report 13). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/mitigation-matters-report/from-the-ashes