Understanding Flood Mitigation Implementation Activities in Minnesota’s Red River Basin

Publication Date: 2024

Abstract

This study sought to better understand factors that facilitate or hinder flood mitigation implementation in rural settings. The Red River Basin in Minnesota—an area that encompasses all or part of 18 predominantly rural counties—provided a unique setting in which to study local implementation and adoption of mitigation strategies in a rural context. Flood mitigation efforts in this region have been managed for the past 25 years using a consensus-based framework that established a collaborative approach to flood damage reduction efforts. This approach has been marshaled by a Flood Damage Reduction Work Group (Work Group) made up of representatives from local watershed districts, the state Department of Natural Resources, environmental interest groups, citizens, and other federal and state partners. This study employed semi-structured interviews with Work Group members and key partners—as well as review of important documents related to the Work Group’s operations and observation of Work Group meetings—to learn more about this novel approach to flood mitigation and its influence on implementation. The results of this study showed that successfully completing a project—or not—hinged on three key components: landowners, permits, and funding. Seven overarching and related factors were identified that appeared to positively affect all three components and facilitate completion of projects. Theoretical and practical implications of these findings—for both rural and other settings—are discussed.

Introduction

Floods have historically been the most widespread, deadliest, and costliest natural hazard in the United States (Cigler, 20171). The combination of climate-driven increases in extreme precipitation events and demographic shifts suggests that the risks posed by flooding will only increase as the 21st century progresses (e.g., Swain et al., 20202; Wing et al., 20223). Rising impacts from floods and the growing number of people affected by them are evidence enough that mitigation efforts are presently insufficient, regardless of what happens in the future (Wing et al., 2022). It follows that a clear understanding of the factors that influence implementation of mitigation strategies—and how to manipulate those factors towards sustainable and positive outcomes—is more important than ever.

While the United States is becoming increasingly urbanized, 14% of the population (over 46 million people) are rural residents and 72% of U.S. landmass is classified as rural (Dobis et al., 20214), numbers that are not insignificant. Additionally, strategies leveraging rural land, such as those that reduce flood volume, create temporary storage, or increase conveyance capacity, have been increasingly recognized as important tools for managing flood risk at a catchment or basin scale (Gianotti et al., 20185; Rouillard et al., 20156). Yet little research has specifically examined flood implementation efforts in a rural setting, at least in the United States (Consoer & Milman, 20177; Gianotti et al., 2018; Mukherji et al., 20238; Seong et al., 20229). The Red River Basin in Minnesota—an area that encompasses all or part of 18 predominantly rural counties (Red River Basin Commission, 201110)—provides an intriguing setting in which to study local implementation and adoption of mitigation strategies in a rural context.

Background

The Red River of the North originates at the confluence of the Boise de Sioux and Ottertail Rivers between North Dakota and Minnesota, forming the border between the states as it flows northward towards Lake Winnipeg in Canada (North Dakota Department of Water Resources, n.d.11). But while the river and its watershed form a “vast and beautiful region on the eastern edge of the Great Plains” (Red River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Working Group, 2001, p. 312), it is an expanse prone to flooding. The geological youthfulness and geographic flatness of the region, combined with the perils of a northward flow—namely ice dams and synchrony of runoff with the spring thaw—all contribute to flood vulnerability in the Red River Basin (Schwert, 200313). Minor flooding happens most years (North Dakota State University, n.d.14), with major floods occurring most recently in 1979, 1997, 2006, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2019, and 2022 (Harbo, 202215; Red River Basin Commission, 2011).

In Minnesota, watershed districts, counties, cities, and townships can all play a role in local flood mitigation efforts (Minnesota Board of Soil and Water Resources, n.d.16). Within Minnesota’s portion of the Red River basin, the Red River Watershed Management Board—whose membership includes seven watershed districts—is a regional entity created in the late 1970s to promote a basin-wide perspective centered on flooding (Minnesota Board of Soil and Water Resources, n.d.). In response to a lawsuit brought by the Red River Watershed Management Board and its watershed districts against the United States Army Corps of Engineers and Minnesota Department of Natural Resources related to longstanding flood control disputes, the Minnesota Legislature mandated a “mediation” process to resolve these issues (Red River Basin Commission, 2011; Red River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Work Group, 199817). The result was the convening of a Flood Damage Reduction Work Group (from here on out referred to as the Work Group), comprised of representatives from the Department of Natural Resources, the Red River Watershed Management Board, environmental interest groups, citizens, and other federal and state partners. The Work Group created a consensus-based “framework for a new, collaborative approach to implementing both flood damage reduction and natural resource protection and enhancement in the Red River Basin in ways that will benefit all Minnesota’s citizens” (Red River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Work Group, 1998, p. 1).

The Work Group identified key elements to this approach as “clearly identified goals, comprehensive watershed planning, early consultation and collaboration on flood damage reduction projects among stakeholders, and a cooperative approach to permitting of those projects” (Red River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Work Group, 1998, p. 1). For the past 25 years, the Work Group has successfully continued to achieve the goals outlined in the framework, which came to be called the 1998 Mediation Agreement (Red River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Work Group, 202018). This legislated collaborative approach—an approach that the researcher found entirely unique to the Red River Basin—establishes a rich environment from which to gather data to better our understanding of what influences implementation of flood mitigation strategies at the local level in a rural context.

Literature Review

Mitigation can be defined as “sustained action taken to reduce or eliminate long-term risk to people and their property from hazards and their effects” (Congressional Research Service, 2022, p. 219). In the United States, flood mitigation has pivoted away from a flood protection approach—defined as a highly federalized and structural approach to mitigating flood risk—towards an approach of flood risk management (Galloway, 200820). This approach goes beyond federally backed engineering solutions to recognize the importance of non-structural approaches based on adjustment of human activities (Brody et al., 201021); the necessity of involvement at lower levels of government and non-governmental entities (Tyler et al., 201922); and the interdependence of physical, social, political, and ecological factors in the creation of flood risk (Brody et al., 2010).

This shift in approach has meant that responsibility for implementing flood mitigation has increasingly transferred to the local level, with state and federal entities intended to support and facilitate their efforts (e.g., Brody et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 202323; Mukherji et al., 2023). Yet, local level flood mitigation strategies—both structural and non-structural—have not been uniformly realized across jurisdictions, with some locales accomplishing more than others (e.g., Brody et al., 2010; Consoer & Milman, 2017; Mukherji et al., 2023; Reddy, 200024). A synthesis of literature across a variety of disciplines suggests several factors—oft interrelated—that may influence adoption and implementation of mitigation at the local level generally. It is important to note that, within the literature, only some studies have looked at flood mitigation specifically (e.g., Brody et al., 2010, Consoer & Milman, 2018) while others have looked at mitigation implementation more broadly (e.g., Prater & Lindell, 200025) and still others have considered other hazards (e.g., Alesch & Petak, 200126; Olson & Olson, 199327; Reddy, 2000). The extent to which all these factors then would influence flood mitigation specifically remains an open question.

Mitigation adoption can be influenced by the degree to which a community perceives itself at risk from a hazard, informed by its past experiences, vulnerabilities, and tractability of the hazard (Brody et al., 2010; Burby & Dalton, 199428; Burby & May, 1998; Prater & Lindell, 2000). The extent to which a community has the financial, technical, and human resources to implement mitigation strategies heavily sways its decision to do so (e.g., Alesch & Petak, 2001; Brody et al., 2010; Consoer & Milman, 2018; Mukherji et al., 2023). Community buy-in and commitment to mitigation (e.g., Berke et al., 199629; Brody et al., 2010; Burby & May, 1998; Dalton & Burby, 199430; Mileti, 198031); leadership and advocacy for mitigation (e.g., Alesch & Petak, 2001; Brody et al, 2010; Prater & Lindell, 2000; Reddy, 2000); linkage of hazard mitigation to other community activities or goals (e.g., Calil et al., 201532; Reddy, 2000); and the existence of a quality mitigation plan borne of a participatory process (e.g., Berke, 1996; Burby, 2003) can also affect mitigation adoption. External factors such as state policies and support (e.g., Berke & French, 199433; Berke et al., 201434; Consoer & Milman, 2018; Hughes et al., 2023; Smith et al., 201335); the structure of federal support and programs (e.g., Consoer & Milman, 2018; Mukherji et al., 2023; Seong et al., 2022); and environmental regulations (Consoer & Milman, 2018) can also influence mitigation efforts, as can the degree of interorganizational coordination and communication (e.g., Brody et al., 2010; Burby & May, 199836; Consoer & Milman, 2018; Mileti, 1980; Prater & Lindell, 2000). Finally, the cost of a strategy and its perceived benefit (e.g., Brody et al., 2010, Mileti, 1980; Olson & Olson, 1993); the timeline of implementation (Brody et al., 2010); and the degree to which a proposed project or policy adapts to stakeholder concerns (e.g., Brody, 200337; Alesch & Petak, 2004) may also shape mitigation decisions.

As noted in the introduction, research has highlighted the potential of various flood mitigation strategies in rural areas to manage flood risk, particularly at a catchment or basin scale (Gianotti et al., 2018; Rouillard et al., 2015). Yet, few studies have considered local flood mitigation implementation specifically within the rural context (Consoer & Milman, 2017; Gianotti et al., 2018; Mukherji et al., 2023; Seong et al., 2022). Conflicting perspectives suggest that on one hand, rural communities “are especially at risk and, due, to scarce local resources and chronic underinvestment, are less able to reduce vulnerability, adapt to climate change and recovery from disasters” (Mukherji et al, 2023, p. 4). On the other hand, rural communities exhibit strong social capital and sense of community, as well as a high level of self-reliance (Jerolleman, 202038, 202139; Mukherji et al., 2023). The former view might suggest rural communities’ limited ability to manage flood risk, while the latter might lead to a more optimistic interpretation. The limited work done to date has understandably not yielded a clear understanding of the effect of the rural context as it relates to the factors that influence mitigation implementation.

Research Questions

This research sought to address a gap in the literature to improve understanding of the factors that contribute to successful local flood mitigation implementation in rural settings. In studying the novel collaborative approach to flood disaster mitigation that has guided efforts in Minnesota’s Red River Basin for the past quarter century, this research examined the following questions:

What factors have facilitated positive progress towards floods mitigation implementation?

What barriers or challenges have been encountered while working towards flood mitigation efforts?

Research Design

The researcher determined a qualitative approach suitable for this study given the novelty of the approach instituted by the Mediation Agreement and the complexity and progressive nature of its implementation over time. The researcher further determined that the most applicable place to start a line of scholarly inquiry on this topic was immersion into detailed data offered by those with the most pertinent experiences—namely with current members of the Work Group and with representatives from organizations not part of the Work Group, but who were identified as partners or stakeholders in their work (e.g., engineering firms, non-profit organizations, county governments, etc.). The Red River Watershed Management Board and Work Group leadership supported this study by providing the list of Work Group representatives, allowing the researcher to give a short description of research at a regular meeting to solicit interview participants, being accessible for follow-up questions, and facilitating access to foundational documents.

This study relied primarily on in-depth, semi-structured interviews conducted with individuals in the roles identified above. A total of 19 individuals agreed to be interviewed for this study. To maintain confidentiality, an exact organizational breakdown cannot be provided. However, state-level agencies, the Red River Watershed Management Board, local watershed districts, and other Work Group partner/stakeholder agencies were well-represented, while no federal-level representatives chose to participate in this research. Table 1 shows a breakdown of the organizational placement of participants. Of note, one citizen representative had agreed to participate, but unfortunately was unable to do so for health reasons.

Table 1. Participants’ Organizational Placement

Data collection commenced following Institutional Review Board approval on January 9, 2024, and continued until July 3, 2024. Interviews followed Rubin and Rubin’s (2012)40 responsive interview model. All interviewees reviewed a study information sheet and signed an informed consent form prior to the interview. An interview guide aided the actual interview process and covered the following broad topics: background/experience/role within flood damage reduction in the Red River Basin; understanding of the Mediation Agreement and the Work Group; assessment of progress towards flood damage reduction goals; and perceptions of barriers to/facilitators of flood damage reduction efforts. Most interviews were conducted in person either at the participant’s office (n=13) or at the Red River Watershed Management Board office building (n=2). One interview was completed at a mutually convenient coffee shop and three interviews were completed virtually using Microsoft Teams due to time and geographic constraints. Interviews ranged in time from 20 minutes to 1.5 hours; length was determined by the participants’ availability and responses to questions.

Philips (2012) challenges disaster researchers using qualitative methods to incorporate data-gathering techniques beyond the interview. To that end, this study collected and reviewed over 30 key documents related to the Mediation Agreement, the Red River Watershed Management Board, and the Work Group, including addendums to the original agreement, mission statements, reports, budgetary information, and other documents (see Appendix A for a list of documents). The researcher also attended and observed two regular meetings of the Work Group, two regular meetings of the Red River Watershed Management Board, and the joint annual conference of the Work Group and the Red River Watershed Management Board. In addition, the researcher visited multiple project sites from the south to north end of the basin. Using these additional data collection strategies “allows the researcher to enhance the creditability and trustworthiness of the data and findings, permits that desirable thick, rich context to develop, and facilitates emergent questions and problems” (Philips, 2012, p. 20541).

Interview data was analyzed using Rubin and Rubin’s (2012) responsive interviewing model. Thus, data analysis began concurrently with the collection and transcription processes. Line-by-line, in vivo, and focused coding was used in conjunction with analytic memos and concept maps to identify emerging categories and conduct theoretical sorting. Documents and observation notes served to corroborate and triangulate findings (Yin, 200342). ATLAS.ti (v.24) software was used to facilitate the data analysis process.

Findings

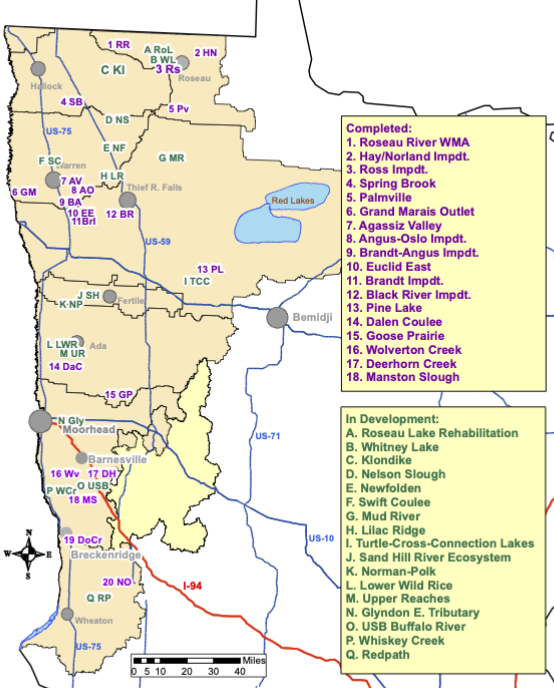

There have been 18 major flood mitigation projects completed in Minnesota’s Red River Basin since the inception of the Work Group in 1998, with an additional 17 projects in various stages of development at the time of this writing. Figure 1 shows the location of these projects.

Figure 1. Projects Completed or Under Development Since Establishing the Flood Damage Reduction Work Group Process in 1998

These projects have included a variety—and typically combination—of strategies, including building off-stream storage impoundments; restoring and rehabilitating stream channels and floodplains; creating or restoring wetland-like structures; developing setback levees; establishing riparian buffer strips; retiring agricultural land from production; and improving drainage and culvert sizing. Moving these projects from exploration through to finished construction has proven a complicated and lengthy process (see Appendix B for diagram of the process)—it regularly takes a project five to 10 years to reach fruition, with some even surpassing the decade mark. It has also proven expensive, with individual project costs ranging from just shy of $1 million to upwards of $60 million, depending on size and complexity. Participants coalesced around perceptions that successfully realizing a project—or not—hinged on three central components: landowners, permits, and funding.

Landowners

Constructing large-scale flood mitigation projects requires finding sufficient land to host said projects, land that is oftentimes privately owned. Convincing private landowners to give up their land—either through outright sale or easement—is not an easy feat and is certainly not guaranteed at project onset. As noted by one participant:

I think maybe the number one thing is land. If you’re going to build a project, certainly to store water, and especially, you know, if you want to store a lot of water, you need a bunch of land. Land, in northwestern Minnesota tends to be privately owned productive farmland. And if you store water on it, it’s not going to be productive farmland anymore. So, you would have to persuade landowners to sell their land to a government agency or watershed district or the state or whatever. And, they’re not very interested in doing that.

Land in northwestern Minnesota tends to be privately-owned productive agricultural land, and those who farm it are hesitant to sell it to a government agency or watershed district. Agricultural productivity alone is not the only hurdle to inducing private landowners to sacrifice their lands for the sake of flood mitigation efforts. Landowners reportedly express unwillingness to divest their holdings—productive and more marginal alike—for a variety of other reasons, including historical family ties, recreational pursuits, misunderstanding of mitigation benefits, perception that their land is targeted more than others, or general mistrust of government, among other reasons.

A variety of approaches may be needed to obtain the land necessary to complete a project. In some cases, “money talks,” meaning that adequately compensating landowners may be enough. For others, understanding landowner concerns and trying to address them specifically and individually may be required; for example, ensuring continued access to land for recreational pursuits or farming may be a suitable compromise. Being able to demonstrate a local benefit is also important when dealing with landowners. As one participant noted, “It can’t be that a landowner is sacrificing what they own just to benefit something way downstream; there has to be a local benefit, so you have to make sure you are making things better locally.” Importantly, the local benefits of a project do not necessarily have to be limited to flood reduction but can include other advantages like water quality improvements or increased recreational opportunities. In some cases, recognition of staunch landowner opposition might lead to a decision to pursue an alternative solution or even shelve a project, as no landowners equals no project. As one participant concluded, “And, so, if the project is not workable or acceptable to landowners, you have no project.”

Given the importance of landowners, including them early in project development to find mutually agreeable solutions and generate buy-in can be helpful. As one interviewee stated, “So that may be the most important part is making sure that you are working with landowners, not trying to force things on them or push things on landowners that just don’t work for them.” Inviting landowners to a meeting or conversation about a project should be multifaceted, using outreach such as newspapers, radio, social media, website posts, and mailers. However, the best way to reach landowners is personal contact through someone they know and, ideally, trust, such as a watershed district board member, neighbor, or other recognized member of the local community. When engaging with landowners, it is also necessary to provide information about the project in multiple formats and communicate with them in ways in which they are comfortable engaging; one-on-one conversations are especially useful. As one participant highlighted:

You also have to know your landowners. We have a lot of farmers who are not comfortable getting up at a presentation style meeting, raising their hands, and asking questions. Sure, they will go up to somebody at a map and talk in a small group or one on one with folks. So we when we set up a meeting, we try to provide a variety of options and timeframes so that people have many opportunities in many different formats to be heard and to ask questions. So we provide it in a presentation, we provide handouts, we provide maps so that people have various ways to intake that information.

Ultimately, convincing private landowners to part with their land or rights to their land means creating a two-way channel in which to discuss project alternatives, hear landowner concerns, work collaboratively to find ways to address those concerns, and discuss meaningful local benefits to landowners. Continued and robust communication with landowners throughout the project process—not just in the development stage—is necessary for their continued support.

For some projects, building on public land owned by either state or federal entities is an option that may prove a good alternative to working with private landowners. However, the current statutory basis of those lands—often relating to wildlife and other ecological benefits—means that the lands cannot be forfeited for water storage or other flood mitigation strategies. Additionally, depending on the project, a joint powers agreement might need to be settled between different levels of government. Thus, using public land for projects—while perhaps easier than negotiating with individual private landowners—is not a panacea to the land challenge. Collaboration, buy-in, and collective problem-solving are all necessary for public land arrangements to work.

Permits

Successfully navigating the regulatory framework—more colloquially discussed by participants as “getting the required permits”—is a compulsory, but challenging, part of completing large-scale flood mitigation projects. The underlying reasoning behind, and value in, permitting requirements is to ensure that environmental and other regulations are being followed. While the benefits of these processes are recognized by those working on flood mitigation projects, they lament the sheer number needed from different agencies across different levels of government. As one interviewee stated:

I will say permitting can still be a challenge. Some of these projects can or will take 10 to 15 permits. I think the most I’ve seen is 14 permits and it is primarily state and federal. But sometimes, townships can come into play with a culvert permit or county road authorities. But really, it’s the state and federal permitting.

Most of the required permits are at the state level with the Department of Natural Resources, the Board of Water and Soil Resources, or the Pollution Control Agency, as well as at the federal level with U.S. Army Corps of Engineers or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Working through the various permitting requirements of these assorted agencies requires time, money, and effort. A particular challenge is the complex and bureaucratic nature of permitting: comprehending the varying requirements associated with each agency’s regulations and navigating their diverse organizational arrangements is no easy feat. As summarized by one participant:

There’s still a lot involved in crossing all of those T’s and dotting all of those I’s. All the rules and cultural resources, and the wetland delineations and the minutia. Some of it can bog you down.

Given the length of time over which projects unfold, permitting can sometimes also feel like a “moving target” with amendments being made to current legislation or new legislation being passed. As environmental regulatory frameworks change at both the state and federal levels, so does what is permittable and what is not. Changing environmental laws translates to difficulty surmounting the bureaucratic particulars of the permitting process. As stated by one interviewee:

And at the federal level, we keep fiddling around with the wetland laws, waters of the U.S. and all that, and it doesn’t help. We just need consistency with what’s going on with permitting at all levels.

Those who must navigate these processes thus desire consistency in regulatory frameworks. Agency employees also play a role in obtaining permits: their interpretations of regulations, willingness to engage in early conversations without final plans and efficiency with the bureaucratic aspects of the permitting process were all mentioned as potentially influencing the ease of obtaining permits. As one interviewee stated:

A lot of that is just based on the individuals that you are working with. It’s like anything else, certain individuals can make small issues big deals and other people realize what’s important. And so that’s up to the agencies to make sure that they’re putting good people in these permit review positions that understand the big picture on the resource that they are trying to protect and what battles are important and what battles are not important.

As with legislation, changing agency personnel over the course of a project created, at times, a perceived “moving target” for permits given individual influence on the process.

Despite a complicated regulatory framework at both the state and federal level, creating an alternative project capable of receiving the necessary permits can generally be accomplished. Early coordination of permitting agencies in the project development process with knowledgeable, committed, and empowered agency personnel can aid in this positive outcome. However, successfully permitting a project requires tenacity and commitment at the local level because there is a lot of time involved to work through the intricacies of each agency’s regulations and bureaucracy, as well as funding needed to pay for the privilege.

Funding

Completing large-scale flood mitigation projects requires significant money—multiple millions of dollars in most cases. Costs include not just land acquisition and permitting, but also costs associated with study, design, coordination, and construction. Increased inflation in recent years has also led to increased costs. Local watershed districts can bring some money to the table through their levying authority, but this income alone is largely insufficient to complete one or more major capital projects.

The Red River Watershed Management Board, also with taxing authority within its member districts, is a unique funding source in that half of its levy proceeds return to each watershed district for their identified projects. The other half goes into the Board’s general fund and can be used to support the development, construction, and maintenance of projects across the basin. The Red River Watershed Management Board effectively pools tax monies from member districts and, using an established decision-making process, provides funding for projects that benefit the entire basin, such as data collection using remote sensing methods or hydrologic modeling. The Board also funds individual watershed projects that contribute to basin-wide water management goals. One local watershed district representative summed up the value of the Board from a funding perspective, saying, “The Red Board itself is really key with us in our specific district because they’re like our rich uncle. They’ll provide funding for the projects that we obviously cannot.”

The Flood Hazard Mitigation Grant Assistance Program administered by the state Department of Natural Resources has historically been a significant source of funding for large-scale mitigation projects. The program has been an especially attractive option because the standard 50/50 state-local cost share requirements—which can be met using a combination of local watershed district and the Red River Watershed Management Board funds—may be increased to 75/25 for projects planned and designed under the mediation agreement process. However, this funding, which had flowed freely into the Red River Basin for many years, has started to dry up in recent times. Funding initially started to slow as the percentage of overall financing from the Flood Hazard Mitigation program allocated to the Red River Basin decreased; however, as of this year, funding has essentially been halted statewide. As one participant said of the Flood Hazard Mitigation program:

In the past, I would say 10 years, there’s been a lot less funding available. The funding comes from Minnesota state bonds, which are approved and appropriated by the state legislature. Usually, every other year is considered a bonding year. And, in the last 10 years or so, the legislature has just chosen not to put very much money into state bonding program that supports the Flood Hazard Mitigation funding. So, there’s still funding there, but it’s not enough to fully meet the demand that the local watershed districts have in identified projects.

There is no singular or concrete answer to the reason for the state’s shift away from the Flood Hazard Mitigation program; speculation ranges from changing risk perceptions in the state capital spurred by the lack of recent major city flooding to perceived political maneuverings around bonding bills. Additional proposed factors include retirement of once influential state legislators, project fatigue, or perceptions that the state has already spent enough on flood protection in the region.

To continue to move forward on projects means going beyond the Flood Hazard Mitigation program for funding. Fortunately, though state funding is drying up through the program, money seems to be more readily available at both the state and federal level for addressing water quality and wildlife habitat concerns. To solve the funding challenge, projects have increasingly become more multifaceted, meaning that in addition to flood mitigation benefits, projects are incorporating water quality, natural resources, or recreation components. These elements can potentially open up new categories of funding from state sources such as Board of Water and Soil Resources clean water funds, Department of Natural Resources conservation partner legacy funds, or Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council funds, as well as federal funding through U.S. Fish and Wildlife or Natural Resource Conservation Service programs. As summarized by one local watershed district representative, “Our most successful projects are ones that are multipurpose. So, if we can bring in diverse funding partnerships, that’s where we are most successful.”

Developing multipurpose projects and assembling the corresponding funding streams—while seemingly necessary in the current funding climate—is not without challenges. Moving a project forward requires identifying, applying for, securing, and ultimately coordinating and managing these multiple different funding streams, which is time-consuming and difficult. As one watershed district representative stated:

So, I think those funding sources are a game changer, but they’re not easy to use. They’re not easy to coordinate, each one is different. But, we’re trying to supplement the flood damage reduction funds with those sort of habitat funds and trying to figure out how they fit together. And, it’s possible, but not easy. Like every state fund has its own computer system, its own application, its own timelines, its own deadlines, you know, and to put all those overlapping layers on one project can be a real nightmare.

These challenges appeared amplified when discussing federal programs. As summarized by one participant:

The most effective, the most efficient and easiest source of funding has always come from the states. And the least effective and least efficient has been the federal government. When it comes to water resource projects at the federal level, there’s so much red tape. It’s tied to permitting, it’s tied to benefit cost analyses, all of these roadblocks.

The impediments associated with federal programs—hurdles that seem to exist across federal agencies—often lead to determinations to not use federal options at all. The bureaucratic headaches simply outweigh the perceived program benefits.

While perhaps more difficult than in the past, it is still possible to fund large-scale mitigation projects. However, doing so requires more creative thinking to find solutions that incorporate multipurpose aims and corresponding funding sources. Coordinating with different agencies during the project development process can encourage this innovative thinking and amalgamated funding.

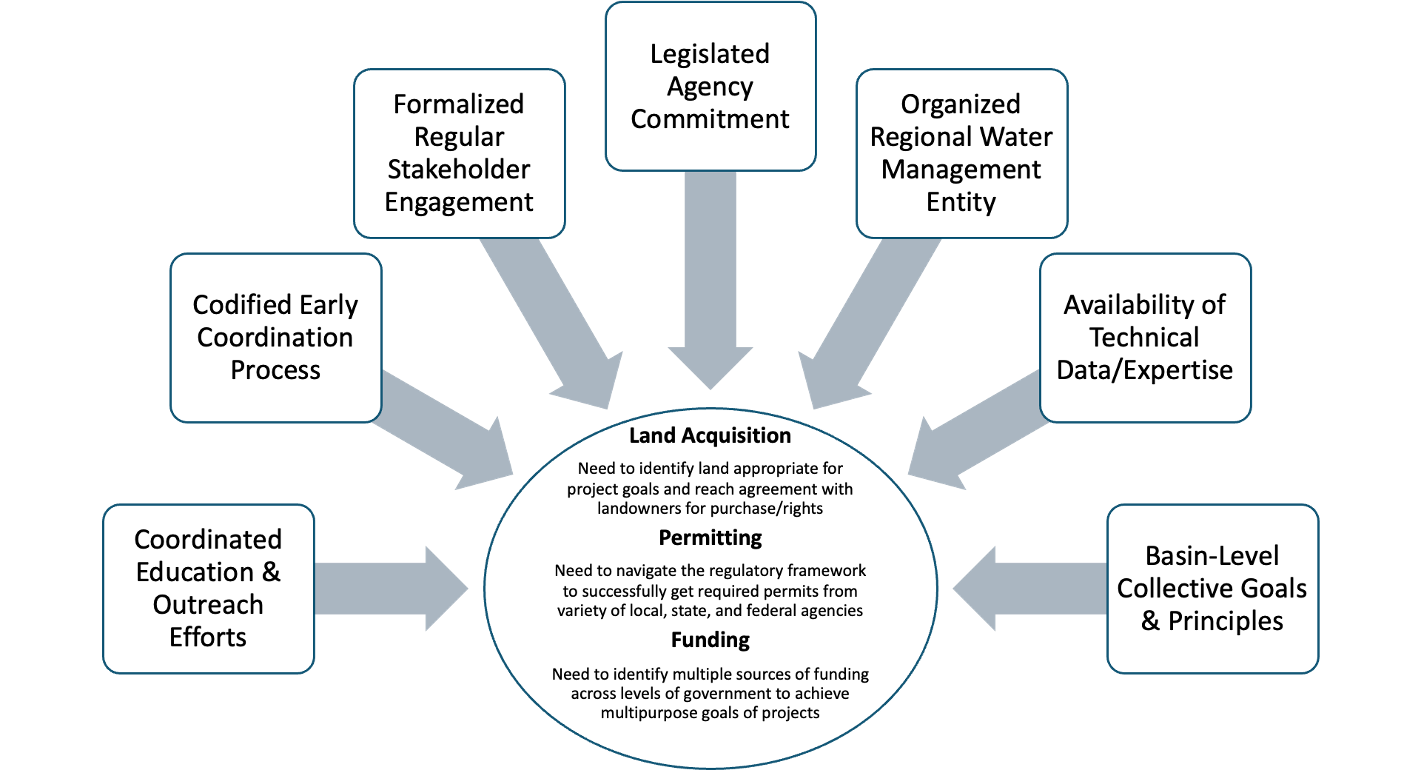

Overarching Factors

This research suggests that accomplishing a large-scale rural flood mitigation project requires successfully addressing land acquisition, permitting, and funding. While influences connected to each of these components were offered in the sections above, there were also seven overarching and interrelated factors stemming from the study context that appeared to positively affect all three and facilitate the completion of projects in Minnesota’s Red River Basin. The interrelated factors are portrayed in two figures below. Figure 2 describes each of these overarching factors and how they can influence mitigation efforts.

Figure 2. Description of Overarching Factors Influencing Flood Mitigation Projects (Click to Enlarge)

Figure 3 shows the overarching factors and how they relate to each other, as well as the three key components of project success. A shift to a graphic depiction in this section is intentional as it is hoped that such a representation of findings may be more useful than descriptive language for distribution to mitigation practitioners. However, to the extent that greater explanation is useful, an in-depth discussion of each of these factors and its influences is located in Appendix C.

Figure 3. Overarching Factors That Influence Rural Flood Mitigation Components (Click to Enlarge)

A key point to reiterate is that these factors are interrelated—one influences another and they work in concert to shape the project components. For example, the codified early coordination process—known as the Project Team process among stakeholders—is contingent on agency commitments to generate meaningful participation; relies on funding and guidance from the Work Group; and uses technical data and knowledge to ground its conversations on project options and alternatives. This process aids in determining how best to navigate land, permits, and funding for a given project. This research would suggest, however, that agency commitment strongly driven by state legislature influence is central to—and, in many ways, the foundation of—the other identified factors. To that end, it is shown at the topmost point of Figure 3.

Discussion

The findings presented above tell the story of the implementation of large-scale flood mitigation projects in Minnesota’s Red River Basin. In this setting, land, permits, and funding are the three critical components that are needed for a project to reach fruition. There are identifiable expediating and limiting influences on each, as well as seven overarching and interrelated factors that appear to also potentially foster the components’ individual achievement, but, perhaps more importantly, ensure their collective congruity. The decision to present the narrative in this way is intentional—it both aligns with how participants explained their mitigation efforts and describes the factors and influences in a way that is most relatable for translation to practice, the critical audience for this report.

The findings could, however, be parsed out differently. A closer look at the findings in the context of the mitigation literature suggests that those factors that influence mitigation in other settings—including urban environments and other hazardscapes—seem to also be present in the rural expanse of northwestern Minnesota. Some of these factors map directly onto the findings as organized. For example, financial resources and technical resources are two factors explicitly found in previous literature (e.g., Alesch & Petak, 2001; Brody et al., 2010; Consoer & Milman, 2018; Mukherji et al., 2023) that also rate their own similarly named heading in this study. Most others, however, find support dispersed in, among, and between the factors and influences described in this research. For example, evidence of the importance of state policies and support (e.g., Berke & French, 1994; Berke et al., 2014; Consoer & Milman, 2018; Hughes et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2012) clearly exists in the findings of this study, but is discussed related to what and how much the state funds, its contributions to the Work Group in terms and personnel and money, and the willingness of state agencies to sign commitment to agreements. That results from the rural context generally support what is already known about mitigation implementation is theoretically important—it suggests that a conceptual model of mitigation implementation could be proposed for testing across settings and hazards. While such model development and presentation are outside the scope of this report, using the data from this study to support that endeavor is a natural extension of this work appropriate for an academic publishing outlet.

Leaving the scholarly realm for the practical one, there are a variety of directions one could take the discussion. Certainly, the findings support at least a brief commentary targeted to state and federal agencies pointing out that there is a perceived need for a more consistent interpretation of regulatory frameworks, as well as a desire for more simplified and intuitive and less redundant systems and processes, both within and between the levels of government. In short, there is still room for improvement in state and federal systems and processes related to funding and permitting for mitigation projects to make them more “user friendly.”

Conclusions

Implications for Practice or Policy

The findings suggest two tangible strategies that those working in local mitigation—regardless of context—may find beneficial for moving projects towards implementation, as these strategies can influence several of the factors on which mitigation implementation relies. These strategies are:

Determine the critical components on which mitigation project success hinges. In the Red River Basin, land, permits, and funding are critical components. All or some of these factors might also play a key role in other, particularly rural, settings. However, in different contexts—especially those that might be more urban—city council approval or certain local ordinances may be the lynchpin to success. Recognizing these fundamental components can allow for identification of the important stakeholders who may control, regulate, or otherwise influence them, as well as an understanding of what additional factors may either positively or negatively affect them. Recognizing key stakeholders and significant influences on critical components can guide further actions toward implementation.

Create a written and formal agreement between key stakeholders. The 1998 Mediation Agreement formalized how citizens, local watersheds, the Red River Watershed Management Board, state agencies, and federal agencies would work together, with representative signatures indicating consent and endorsement. This has formed the basis for continued commitment to finding collaborative solutions to address flood issues for 25 years. Bringing the key identified stakeholders to the table, building consensus around how those stakeholders are going to work together, and codifying that agreement in a written document can serve as the foundation for mitigation implementation activities. Of note, this strategy seems best employed as a general agreement among mitigation stakeholders intended to direct how they approach all projects, but it could also be used on a project-by-project basis. Higher levels of government can influence the existence of such agreements through mandate, which may be necessary if certain partners do not want to come to the table. Ideally, though, higher levels of government can motivate entities to come together through incentives; providing seed funding and adjusting cost-share requirements for projects working under agreements are two examples of such enticements that have been used by the state of Minnesota. Having these agreements be living documents—meaning that they are regularly revisited and resigned—can potentially facilitate longer-term investment of time and resources by stakeholder entities. Depending on local aspirations and situational realities, agreements may inspire regular stakeholder engagement forums, early coordination mechanisms, technical committees, and other targeted structures that can move mitigation efforts forward.

It should be mentioned that determining critical influences and formally agreeing to how stakeholders will engage with mitigation projects could be standalone efforts, as in the present case. These actions could also potentially be incorporated as part of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) local hazard mitigation planning process. However, as currently outlined by FEMA, there seems to be a greater emphasis on identifying and prioritizing proposed mitigation strategies and less focus on determining how the different agencies and entities involved in strategy implementation across sectors and government levels will collaborate to navigate critical components and accomplish the work. Current guidance on implementation highlights assigning a responsible agency, identifying potential resources, estimating a timeframe, and communicating the plan (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 202343) Requirements that incorporate these critical component and collaboration pieces could be strengthened, calling for jurisdictions to outline the processes by which stakeholder entities will work together to address their identified critical components beyond funding. How this information is best incorporated into local mitigation plans—which are typically completed at a county level—at a basin-wide or regional scale would need to be considered.

An additional strategy may be useful in the rural context; specifically, the creation of a regional water management entity to address flood issues across a broader geographic area. Certainly not every locale is going to agree to additional taxation to provide the level of funding that the Red River Watershed Management Board enjoys in Minnesota’s Red River Basin. However, even a less robust and more loosely organized entity may prove beneficial in setting direction, providing leadership, offering a stronger collective voice, and coordinating efforts for the entities it represents. Such a regional organization could be particularly useful in those areas that are resource-strapped or politically limited. However, more research is needed to determine the extent to which a regional water management entity may be beneficial. Studying other river basins in Minnesota or the Red River Basin in North Dakota where no such entity exists could be a next step in answering that question, as could an examination of the local watershed districts in Minnesota’s Red River Basin who are not members of the Red River Watershed Management Board.

Limitations

The exploratory nature of this study combined with the purposive sampling strategy means that the findings in this study may not be generalizable to other settings. The absence of federal and citizen participants introduces the potential of non-response bias—it is possible that these non-respondents may systematically differ from those who did participate (Chambliss & Shutt, 200644). Further research is needed to determine if these findings extend to other rural settings.

Future Research Directions

This study examined the implementation of large-scale flood mitigation projects in the Red River Basin of Minnesota. It found that local watersheds in the basin have been able to successfully navigate land acquisition, permitting, and funding to complete projects. Ultimately, the factors that influence mitigation implementation in this rural setting are similar to those that the literature suggests influence mitigation in other contexts. Future research in other rural areas should confirm this finding; however, it implies that development of a conceptual model of local mitigation implementation is a prospective next step. This study also suggests that determining the critical components on which mitigation project success hinges and creating a written and formal agreement between key stakeholders are two strategies that can have a positive influence on a host of factors that facilitate mitigation implementation and can be executed regardless of context. Creating a regional water management entity may be another beneficial strategy specifically in the rural setting, but more research is needed to confirm this finding.

Acknowledgments. The researcher would like to recognize the participants who volunteered their time to be interviewed and to tour project sites. A special thanks also to Rob Sip from the Red River Watershed Management Board and Andrew Graham from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources who assisted the researcher with gathering key documents and graciously allowed the researcher to attend regular meetings and to announce interview opportunities.

References

-

Cigler, B. A. (2017). US floods: The necessity of mitigation. State and Local Government Review, 49(2), 127-139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X177318 ↩

-

Swain, D. L., Wing, O. E., Bates, P. D., Done, J. M., Johnson, K. A., & Cameron, D. R. (2020). Increased flood exposure due to climate change and population growth in the United States. Earth's Future, 8(11), e2020EF001778. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EF002778 ↩

-

Wing, O. E., Lehman, W., Bates, P. D., Sampson, C. C., Quinn, N., Smith, A. M., Neal, J.C., Porter, J.R., & Kousky, C. (2022). Inequitable patterns of US flood risk in the Anthropocene. Nature Climate Change, 12(2), 156-162. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01265-6 ↩

-

Dobis, E.A., Krumel, T.P., Cromartie, J., Conley, K.L., Sanders, A., & Ortiz, R. (2021). Rural America at a glance. U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102576/eib-230.pdf ↩

-

Gianotti, A. G. S., Warner, B., & Milman, A. (2018). Flood concerns and impacts on rural landowners: An empirical study of the Deerfield watershed, MA (USA). Environmental Science & Policy, 79, 94-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.10.007 ↩

-

Rouillard, J. J., Ball, T., Heal, K. V., & Reeves, A. D. (2015). Policy implementation of catchment-scale flood risk management: Learning from Scotland and England. Environmental Science & Policy, 50, 155-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.02.009 ↩

-

Consoer, M., & Milman, A. (2018). Opportunities, constraints, and choices for flood mitigation in rural areas: Perspectives of municipalities in Massachusetts. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 11(2), 141-151. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12302 ↩

-

Mukherji, A., Curtis, S., Helgeson, J., Kruse, J., & Ghosh, A. (2023). Mitigating compound coastal water hazards in Eastern North Carolina. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 67(8), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2023.2183112 ↩

-

Seong, K., Losey, C., & Gu, D. (2022). Naturally resilient to natural hazards? Urban–rural disparities in hazard mitigation grant program assistance. Housing Policy Debate, 32(1), 190-210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2021.1938172 ↩

-

Red River Basin Commission. (2011). Red River Basin Commission’s long term flood solutions for the Red River Basin. https://wrl.mnpals.net/islandora/object/WRLrepository%3A3790 ↩

-

North Dakota Department of Water Resources. (n.d.). Red River Basin. https://www.swc.nd.gov/basins/red_river/red_river.html ↩

-

Red River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Working Group. (2001). A user’s guide to natural resource efforts in the Red River Basin. https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/aboutdnr/reports/redriver_nrefforts_pdf4.pdf ↩

-

Schwert, D.P. (2003). A geologist’s perspective on the Red River of the North: History, geography, and planning/management issues. https://www.ndsu.edu/fargo_geology/documents/geologists_perspective_2003.pdf ↩

-

North Dakota State University. (n.d.). Geology of Fargo. https://www.ndsu.edu/fargo_geology/whyflood.htm ↩

-

Harbo, I. (2022, April 14). Since 1998, greater Grand Forks has had six more major floods. The Grand Forks Herald. https://www.grandforksherald.com/news/local/since-1997-greater-grand-forks-has-had-six-more-major-floods ↩

-

Minnesota Board of Soil and Water Resources. (n.d.). Partners. https://bwsr.state.mn.us/watershed-districts ↩

-

Red River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Working Group. (1998). Red River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Work Group agreement. http://sandhillwatershed.org/project%20team%20PDF%20minutes/Mediation%20Agreement%20[12_9_1998].pdf ↩

-

Red River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Working Group. (2020). Missions, principles, practice. https://mfiles.wildricewatershed.org/mfiles_rrwmb/#CC774983-AC09-4666-81D9-8B8AAA310342/views/V102/V107 ↩

-

Congressional Research Service (2022). FEMA hazard mitigation: A first step toward climate adaptation. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46989 ↩

-

Galloway, G. E. (2008). Flood risk management in the United States and the impact of Hurricane Katrina. International Journal of River Basin Management, 6(4), 301-306. https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2008.9635357 ↩

-

Brody, S. D., Kang, J. E., & Bernhardt, S. (2010). Identifying factors influencing flood mitigation at the local level in Texas and Florida: The role of organizational capacity. Natural Hazards, 52, 167-184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-009-9364-5 ↩

-

Tyler, J., Sadiq, A. A., & Noonan, D. S. (2019). A review of the community flood risk management literature in the USA: Lessons for improving community resilience to floods. Natural Hazards, 96, 1223-1248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-019-03606-3 ↩

-

Hughes, S., Resor, C., & Newberry, H. (2023). State policy and local resilience: Evaluating state policies for flood resilience in the Great Lakes region of the United States. Climate Policy, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2023.2242309 ↩

-

Reddy, S. D. (2000). Factors influencing the incorporation of hazard mitigation during recovery from disaster. Natural Hazards, 22, 185-201. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008189725287 ↩

-

Prater, C. S., & Lindell, M. K. (2000). Politics of hazard mitigation. Natural Hazards Review, 1(2), 73-82. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2000)1:2(73) ↩

-

Alesch, D. J., & Petak, W. J. (2001). Overcoming obstacles to implementing earthquake hazard mitigation policies: Stage 1 report. Buffalo, NY: Multidisciplinary Center for Earthquake Engineering Research. ↩

-

Olson, R. S., & Olson, R. A. (1993). “The rubble's standing up” in Oroville, California: The politics of building safety. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 11(2), 163-188. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072709301100 ↩

-

Burby, R. J., & Dalton, L. C. (1994). Plans can matter! The role of land use plans and state planning mandates in limiting the development of hazardous areas. Public Administration Review, 229-238. https://doi.org/10.2307/976725 ↩

-

Berke, P. R., Roenick, D. J., Kaiser, E. J., & Burby, R. (1996). Enhancing plan quality: Evaluating the role of state planning mandates for natural hazard mitigation. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 39(1), 79-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640569612688 ↩

-

Dalton, L. C., & Burby, R. J. (1994). Mandates, plans, and planners: Building local commitment to development management. Journal of the American Planning Association, 60(4), 444-461. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369408975604 ↩

-

Mileti, D. S. (1980). Human adjustment to the risk environmental extremes. Sociology and Social Research, 64(3), 327-347. ↩

-

Calil, J., Beck, M. W., Gleason, M., Merrifield, M., Klausmeyer, K., & Newkirk, S. (2015). Aligning natural resource conservation and flood hazard mitigation in California. PLoS One, 10(7), e0132651. ↩

-

Berke, P. R., & French, S. P. (1994). The influence of state planning mandates on local plan quality. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 13(4), 237-250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9401300401 ↩

-

Berke, P., Cooper, J., Aminto, M., Grabich, S., & Horney, J. (2014). Adaptive planning for disaster recovery and resiliency: An evaluation of 87 local recovery plans in eight states. Journal of the American Planning Association, 80(4), 310-323. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2014.976585 ↩

-

Smith, G., Lyles, W., & Berke, P. (2013). The role of the state in building local capacity and commitment for hazard mitigation planning. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 31(2), 178-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072701303100204 ↩

-

Burby, R. J., & May, P. J. (1998). Intergovernmental environmental planning: Addressing the commitment conundrum. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 41(1), 95-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640569811812 ↩

-

Brody, S. D. (2003). Implementing the principles of ecosystem management through local land use planning. Population and Environment, 24, 511-540. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025078715216 ↩

-

Jerolleman, A. (2020). Challenges of post-disaster recovery in rural areas. In S. Laska (Ed.), Louisiana's response to extreme weather: A coastal state's adaptation challenges and successes (pp. 285-310). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27205-0_11 ↩

-

Jerolleman, A. (2021). Building resilience in rural America. Eos, 102. ↩

-

Rubin, H.J. and Rubin, I.S. (2012). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (3rd Ed.). Sage Publications. ↩

-

Philips, B. (2012). Qualitative disaster research: Understanding qualitative research. Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Yin, R.K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2023). Local mitigation planning handbook. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_local-mitigation-planning-handbook_052023.pdf ↩

-

Chambliss, D., & Schutt, R. (2006). Making sense of the social world: Methods of investigation (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. ↩

Kirkpatrick, S. (2024). Understanding Flood Mitigation Implementation Activities in Minnesota’s Red River Basin. (Natural Hazards Center Mitigation Matters Research Report Series, Report 20). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/mitigation-matters-report/understanding-flood-mitigation-implementation-activities-in-minnesotas-red-river-basin