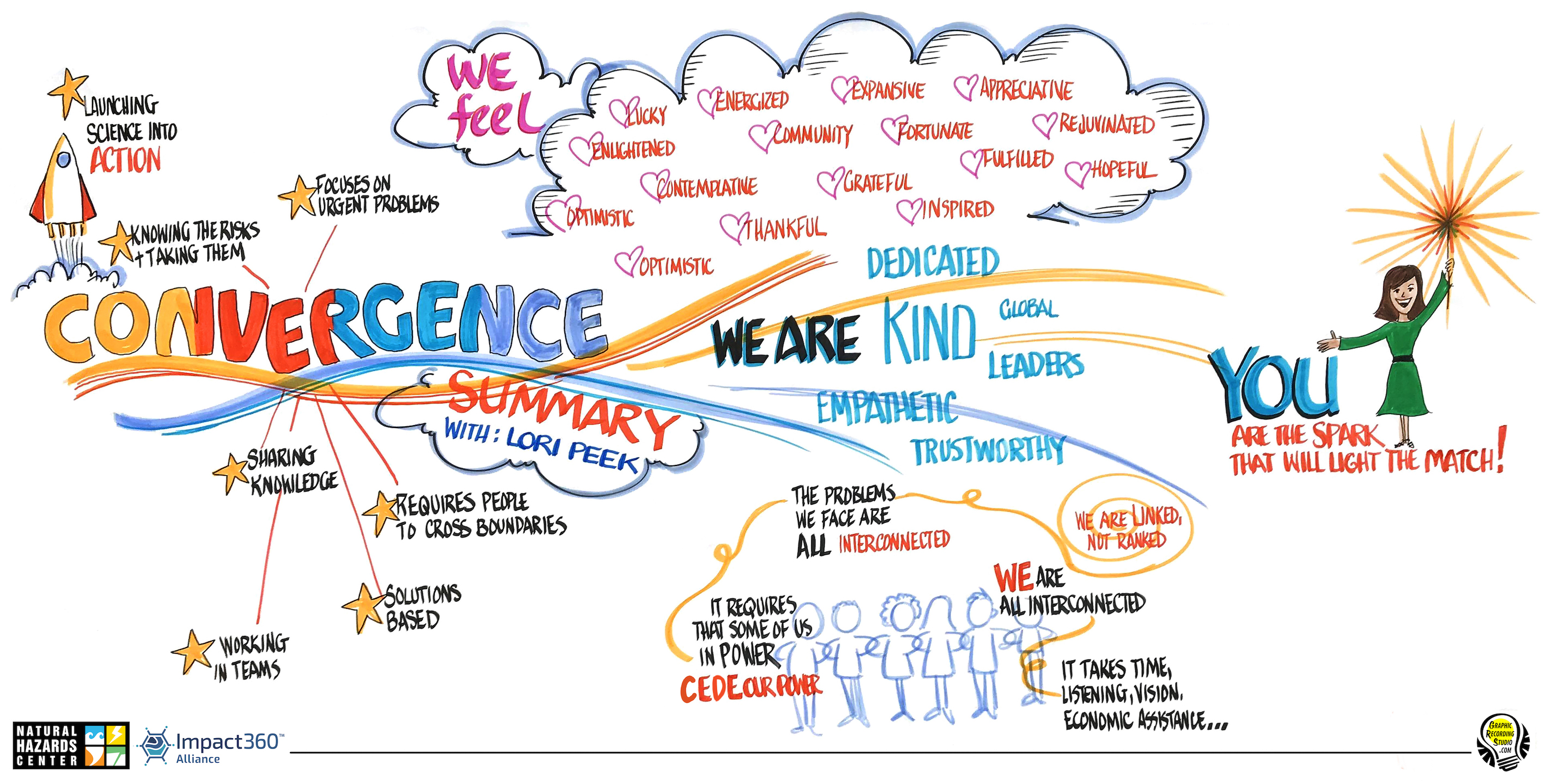

Graphic recording of the wrap-up of the 44th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop. Image created by visual recorder Alece Birnbach, with the generous support of Impact360 Alliance.

Graphic recording of the wrap-up of the 44th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop. Image created by visual recorder Alece Birnbach, with the generous support of Impact360 Alliance.

At each of the annual Natural Hazards Research and Applications Workshops, the Natural Hazards Center Director has issued a closing summary. Gilbert White, our first director and a lifelong Quaker, began this tradition, which he referred to as “offering a sense of the meeting.”

To be able to offer you a sense of this 44th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop, I attended each of the sessions, went to the add-on events, and circulated through the long breaks and lunches, so I could listen to and learn from as many participants as possible. Then, after the Tuesday evening barbeque, I began to synthesize the rich and meaningful conversations that took place during our four days together. I shared the results of that process in my remarks on Wednesday at the close of this year’s Workshop, which was focused on the theme of Convergence: Coming Together to Improve Hazards and Disaster Research, Practice, and Policy.

Attendees at the opening session of the 44th Natural Hazards Workshop. ©Brazos Valley Image, 2019.

Attendees at the opening session of the 44th Natural Hazards Workshop. ©Brazos Valley Image, 2019.

Now, in a more recent tradition started a few years ago, I will use this July edition of the Director’s Corner to share this summary of the meeting, and also as a call to action. A call to converge.

On behalf of the entire Natural Hazards Center team, please know how much we appreciate all of those who dedicated time and resources to attend the Workshop this year. To those who were not able to be there, we hope to welcome you in the future.

Please save the date for the 45th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop, which will be held July 12-15, 2020, at the Omni Interlocken Hotel in Broomfield, Colorado. As usual, the Workshop will be immediately followed by the Researchers Meeting on July 15-16, 2020.

Thank you for the work that you do to reduce the harm and suffering from disasters and advance justice and equity. Your efforts fill me with hope, and I wish you the best in the year ahead.

Lori Peek, Director

Natural Hazards Center

Closing Comments

Coming together.

This is what we have been doing for 44 years in Colorado with this hazards and disaster community.

This year, we have gathered to engage around the idea of convergence. What it is, what it isn’t, and ultimately, why and how we do it.

What is convergence?

Convergence is teams working together toward a common goal and in novel ways—crossing borders and boundaries—to solve vexing social, environmental, and technical challenges.

What is convergence?

Convergence is when some of the world’s most talented scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey shared their data and information with emergency managers and city and regional planners so that they could work together to ensure that hundreds of people—many of whom were living off the grid—could be safely evacuated from a lava flow zone in the face of Hawaii’s Kīlauea volcano eruption.

What is convergence?

Convergence is when students and faculty from the Texas Target Communities initiative are invited into rural and urban communities. When they are asked to lend scientific knowledge and expertise to develop hazards mitigation plans and other solutions alongside and in full partnership with those who know their risks, know their resource limits, and recognize the infinite capacity in their communities.

What is convergence?

John Cooper of Texas A&M University answered that question like this: “I’m not concerned with what it’s called, as long as it helps.”

How is convergence different than interdisciplinary research or simply collaboration?

First, convergence focuses on urgent problems that are so big and so complex and so deeply rooted in our histories, systems, and structures that no one person, discipline, or organization could possibly characterize the full scope of the issue in isolation. Convergence, by its very definition, requires people to cross borders and boundaries.

On Tuesday at the Workshop, Juan Parras—who is one of our greatest living environmental justice advocates and a leader at t.e.j.a.s—spoke of a school in Houston that is surrounded by petrochemical plants. He said that “Every single day those kids in that school face the very real risk of death, injury, and bodily harm.”

It has taken environmental justice advocates, epidemiologists, community scientists, and others to fully characterize that risk. But as Juan also noted, “we know what the problem is, but we have no solution.”

That leads me to the second way that convergence differs from collaboration or interdisciplinary research. Convergence is solutions based. You can have interdisciplinary research without offering a solution. You can collaborate for all kinds of purposes without working toward a solution. But you are not doing convergence, if you are not working together with others to try to develop a solution.

Social scientists and engineers in this community have long studied evacuation dynamics in the context of natural hazards. They have asked, and answered, questions along these lines: Who leaves and who stays in a hurricane? Where do people go? How do available transportation routes affect evacuation decision making? How does damage to the built environment influence long-term displacement?

Some of these questions require an interdisciplinary approach. But they don’t necessarily add up to a solution.

It is when we move into a space of convergence that we can launch our science into action.

During the 2017 hurricane season, Matthew Marchetti and the team at Crowdsource Rescue saved tens of thousands of stranded people. Then in 2018, Matthew started working with and learning from social scientists like Tricia Wachtendorf, James Kendra, Michelle Meyer, and many others about the social and economic drivers of hazard evacuation dynamics. Crowdsource Rescue then brought some of the best technology to bear so that they could continue to mobilize thousands of spontaneous volunteers with vehicles, boats, and other resources to work alongside grassroots organizations to move tens of thousands of elderly, low income, and those otherwise left behind out of harm’s way when the flood waters come.

That is convergence because it entails teams working together toward a common goal to address an urgent and complex problem and to develop a solution in response to that problem.

How do we actually do convergence?

During the 44th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop, participants shared vital lessons about this. Here is what I learned from all of you.

First, we must know that the problems we are confronting are all interconnected.

Shaila Shahid joined us this year from Bangladesh. She immediately recognized that the risks that those school children in Houston face are deeply tied to the flooding that her entire nation is threatened with. Both are about, in part, climate change, natural resource extraction, economic injustice, histories of colonialism, and environmental racism.

Second, we must recognize not only that the problems we face are all interconnected, but we are all interconnected. The actions of one of us can and do affect all of us.

Tiffany Cousins from Virginia Tech summed up that interconnection up by saying, “We all matter to each other, what we do matters, and it is going to take all hands on deck to reduce disaster risk.” Alexis Cordova from Liberty County, Texas, said that interconnection means “we are not at liberty to give up.”

Third, to recognize the full potential and power of that interconnection, it is going to require those in positions of power to cede some of that power.

Nickea Bradley, who is with the Washington, D.C., Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, shared during one of the sessions about how her organization has integrated equity circles into their hazard mitigation work.

Envision that in your mind’s eye for a minute. Envision a circle.

When we stop thinking in a hierarchical, linear fashion, and start thinking and working in circles, we can better see that we are linked—not ranked. That can also help us to recognize that no one person is going to save us from the myriad threats we face. We are going to save us.

Fourth, we must approach this convergence work with a sense of urgency and also the utmost compassion.

David Maurstad from the Federal Emergency Management Agency implored us on Monday morning to never forget how many millions of people are suffering—really suffering—from all of the large-scale disaster events we have experienced in this nation.

On Monday evening, Norman Bert, one of the talented playwrights for After the Storm, said that “every number, every statistic, should have a name by it” to help us to remember the human reality of that suffering.

Fifth, to engage in true convergence work, it is also going to take time, humility, empathy, commitment, scientific rigor, authenticity, listening (like you are a potted plant), patience, recognition, resources, transparency, openness, the capacity to share data and knowledge, democratic governance structures, vision.

Those are your words that I heard you speak this week.

But as Alessandra Jerolleman of Jacksonville State University wisely observed, “there are real costs to this type of convergent engagement, and we don’t always talk about those costs.” She continued, “We also don’t always fully recognize that those who are doing the engaging are often not the ones who have the power to make the change.”

Convergence is difficult. It takes time and serious commitment. And there are real risks.

Erica Kuligowski, of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, asked us to consider, though, “In the absence of convergence, what are the consequences?”

Sara Hamideh, of Iowa State University responded to that question by underscoring that if we do not shift toward this kind of problem-oriented, but also solutions-based, approach—if we do not “do convergence” in a way that is purposeful, goal-oriented, and methodical, then the outcome is predictable.

Sara said this: “We will continue to see rising hazards losses. And we will also see more unjust approaches that only deepen social and economic inequality.”

There is no time to waste. I am looking out right now at a room full of people with infinite potential. I am looking at a room of what I have come to think of as convergence catalysts. You are the sparks on the match that can light the fire. You are cultivating all the seeds in the ground that months or even years from now may blossom into something unbelievably beautiful.

There is much work to be done. We are facing a climate crisis and unprecedented social and economic inequality. There is no time to waste.

As we set out to do this work together, please know I stand before you and beside you with an immense sense of gratitude and respect. As you set off to do this work, I ask, as I always do, that you please take care of yourself and others.

With that, I declare your 44th Annual Natural Hazards Research and Applications Workshop, adjourned.