Graphic recording of the wrap-up of the 48th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop. Image created by visual recorder Alece Birnbach of the Graphic Recording Studio.

Graphic recording of the wrap-up of the 48th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop. Image created by visual recorder Alece Birnbach of the Graphic Recording Studio.

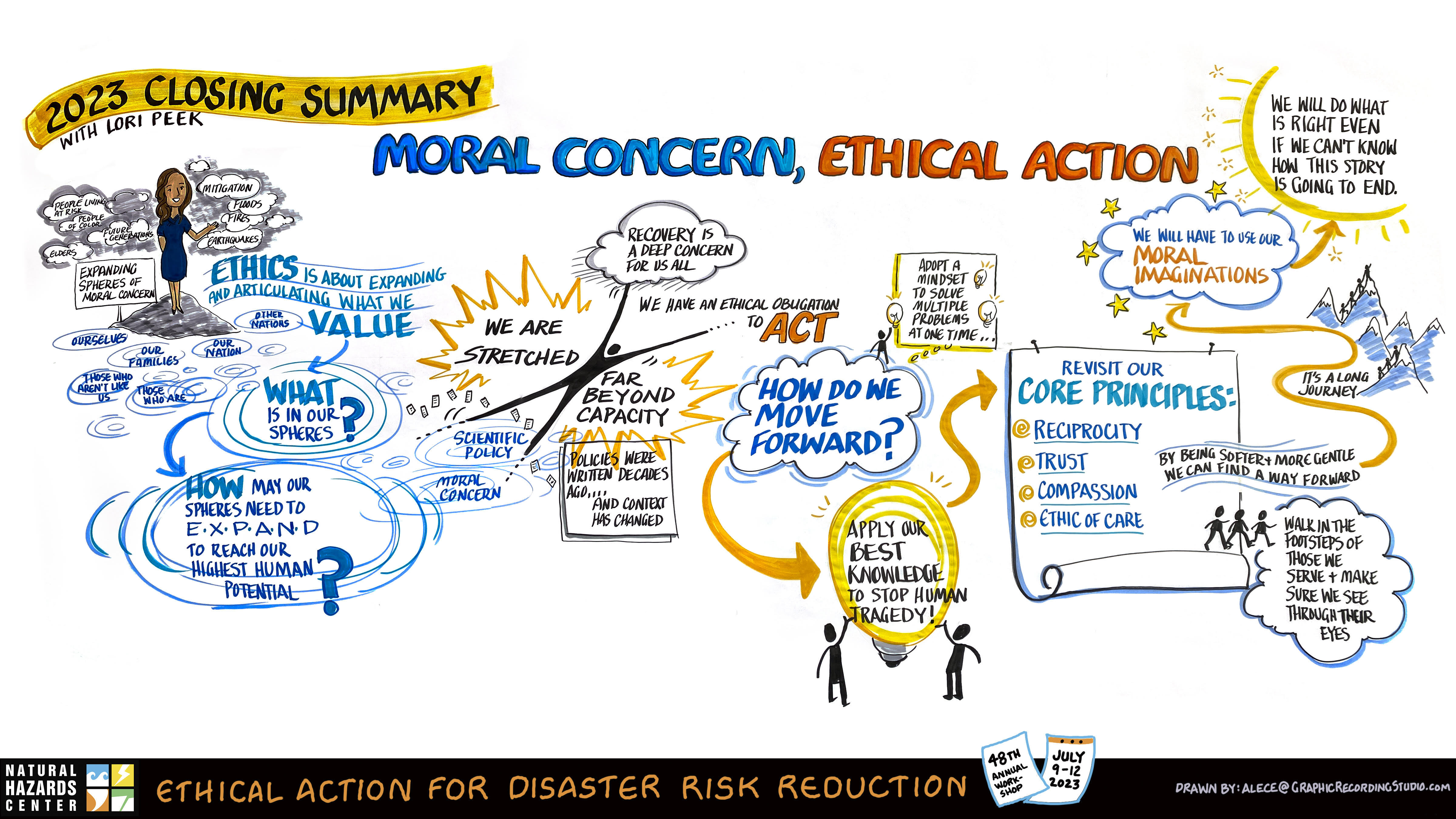

This year at the 48th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop, we centered our conversations around the theme of Ethical Action for Disaster Risk Reduction. During our time together, panelists and participants helped illuminate the intricacies of ethical action as we listened to each other share stories from the frontlines of disaster research and practice.

It has been a long time—1,454 days, to be precise—since we last gathered in Colorado for the annual Workshop. While we were grateful for the technology that allowed us to continue to convene the Workshop during a time of global pandemic, we were overjoyed to be able to welcome people back to Colorado this summer. Therefore, much of this year’s meeting was also dedicated to opening up space for people to reconnect and to build new bridges.

This Director’s Corner offers a lightly edited summary of the 2023 Workshop that I shared at the close of the meeting. It captures some of the key themes that I heard as I moved through each session, listening to the participants share their trials and triumphs as they work toward our shared vision of a world where natural hazards do not become human tragedies. Thank you for taking the time to read this and for the work you do.

Please take care of yourself and others.

Lori Peek, Director

Natural Hazards Center

Closing Comments

What are we concerned with in this community?

Floods. Fires. Earthquakes. Hurricanes. Landslides.

Mitigation, preparedness, response, recovery.

The list goes on.

Who are we concerned with in this community?

All people living at risk. Current and future generations. People of color. Those living in poverty. People with disabilities. Our elders. Children.

The list goes on.

Philosophers have long argued that the history of the moral development of the human race emanates from expanding spheres of moral concern. Think of this like water rippling ever further outward, where we progressively and more carefully consider our duties to ourselves; our families; to those who are similar to us and those who are not; to those of our nation and all other nations; to all living things. As we develop intellectually and morally, we are increasingly able to identify our commonalities, our interconnections, and our ethical obligations to one another and this one beautiful but volatile place we all call home.

On Monday morning, our keynote speaker, Michael Nelson, underscored that “ethics is about examining and articulating what we value.” Moreover, it is about understanding what is in our sphere of moral concern and how that sphere may need to expand if we are to reach our highest human potential. And dare I add, perhaps, if we are to survive.

At this year’s Natural Hazards Workshop, we witnessed how our spheres of scientific and policy and moral concern are all rapidly expanding, stretching the boundaries of our field.

Consider our Tuesday morning plenary session where we heard from four extraordinary Big City Emergency Managers. They identified a truly breathtaking number of interlocking crises that they are increasingly being called to respond to—homelessness, mass shootings, migrant resettlement, cyberattacks, infrastructure collapse, air quality issues, toxic water contamination, and threats of violence against LGBTQ and other marginalized communities.

It should tell us something that the emergency manager for one of our most earthquake-prone cities in the United States, only listed “earthquake” as the seventh most pressing priority on her list.

The rising number of threats and seemingly unending stream of disasters has left members of the hazards and disaster workforce stretched far beyond capacity. As Katie Arrington of Boulder County shared with us, over the past 13 years—as the county has moved from wildfire, to flood, to pandemic, to mass shooting, to wildfire again—there have only been about 60 days in those 13 years where the county has not been in a state of emergency or active recovery.

Boulder is certainly not alone—the number of cities and rural communities and tribal lands locked in these cycles of disaster loss is clearly of moral concern to us all. Not simply because of the damage being wrought to the built and natural environment, but also because of the rising number of people who live forever with the internal wreckage of disaster.

Sometimes policy can help to address these harms. But in other cases, as we well know, even well-intentioned policies can have adverse unintended consequences. As Eric Letvin of the Federal Emergency Management Agency observed, “FEMA is paying attention to the research that shows that dollars aren’t reaching those in distress. The fact is, though, that many of the policies were written decades ago, and our context has changed.”

As that context continues to rapidly shift, and as our spheres of moral concern grow, how do we move forward? David Applegate of the U.S. Geological Survey put it clearly: “We cannot respond our way out of disasters. Therefore, we have an ethical obligation to act.”

How do we find a path forward when everything feels so complicated, so polarized, so urgent, so extreme?

I think a first step will involve returning to the core principles and values that sit at the root of this community. From its inception, the hazards and disaster field has always been dedicated to generating and taking the best knowledge and applying it to reduce disaster risk. That is who we are and what we are about. That is our moral commitment.

In order to achieve our highest potential, it will be vital that we revisit the core principles and values that guide this work. Katherine Browne of Colorado State University named them clearly: reciprocity, trust, compassion, an ethic of care. And as Elizabeth Marino of Oregon State University-Cascades said, “It isn’t that we all agree or see the world the same way. But by being a little bit softer, a little bit more gentle, we might be able to hear one another better and envision a new way forward.”

Revisiting these core principles and recommitting to them is key, but we cannot stop there.

Anne Miller of the Colorado Department of Local Affairs put it this way: “We need to adopt a mindset where we are solving multiple problems at the same time. That is what can help us to ensure we are measuring what matters and effect systemic change.” In order to know—to really know—which problems we need to solve, Carol Parks of the City of Los Angeles, recommends that we “walk in the shoes of those who we serve, and see through their eyes.”

We have a long road ahead of us. This journey is going to require that we exercise our moral imaginations as we continue with our research and our practice. There are going to be peaks and valleys that will sometimes feel insurmountable. But we must always remember that we do this work because we are people of conscience who will do what is right, even if we cannot know how this story is going to end.

As you go forth with the vital work that you do, please remember to take care of yourself and others.

With that, I declare your 48th Annual Natural Hazards Workshop adjourned.