By Lisa Gibbs, Karen Block, Colin MacDougall, John Richardson, Alana Pirrone, and Louise Harms

Implications for Public Health

There are many different ways to help children and teenagers process and recover from disasters. Recovery services should include all different stages of childhood and should restore a sense of safety and stability.

The unpredictability of disasters and emergencies can often leave young people adrift in the terror, loss, and ongoing disruption caused by such events. Research has shown this can have short- and long-term effects on their learning, mental health, and well-being. Thankfully, this research also underpins a framework for planning and reviewing post-disaster programs that support positive outcomes for children and youth.

While research suggests that supportive environments can make a difference, evidence on how to create them is fragmented. It is difficult to conduct strong research in post-disaster environments, and those programs and interventions that have done so tend to address varying factors. This is hardly surprising given the complex interaction of influences on the lives of children and teenagers. It is perhaps, therefore, inevitable that programs to increase their resilience are diverse and difficult to compare.

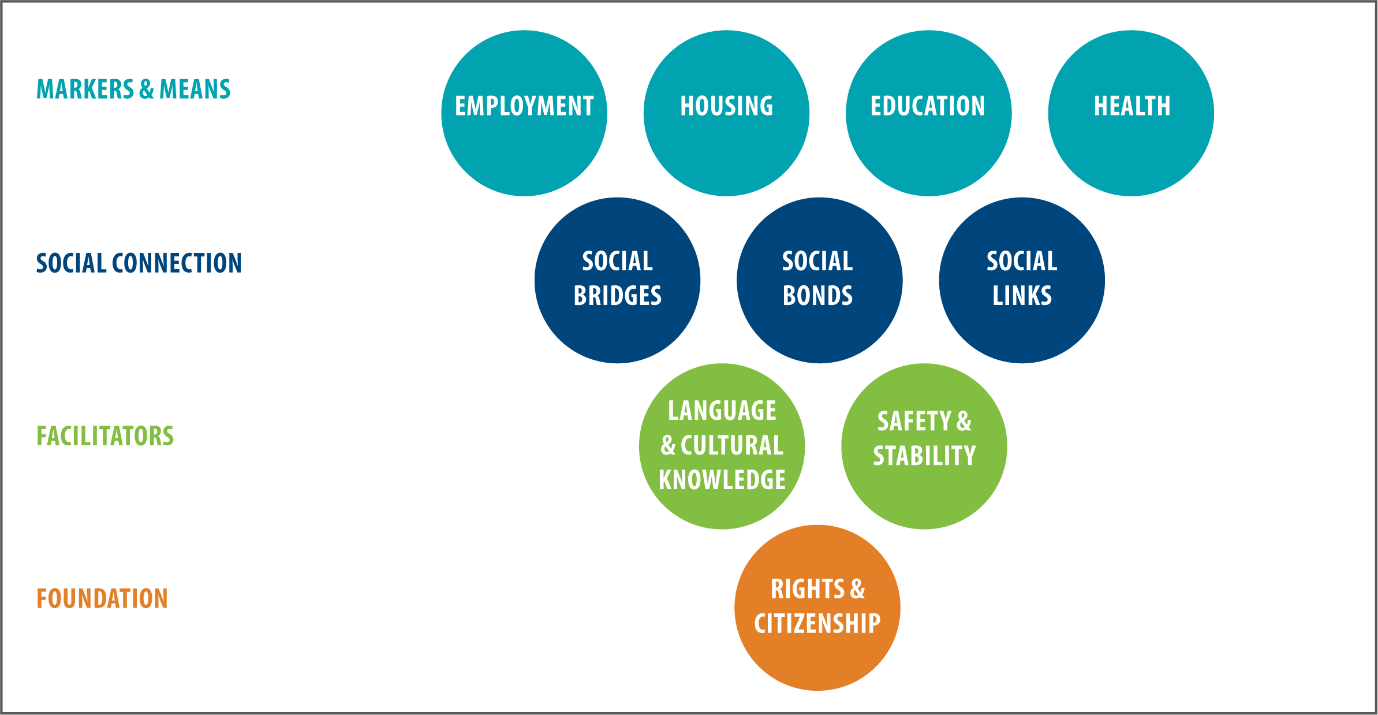

We found it helpful to use a conceptual framework to make sense of the programs and evidence available (see Figure 1) and were struck by how relevant Ager and Strang’s framework for understanding refugee integration was to the experiences of young people facing loss and disruption in the aftermath of a disaster—even though it was originally developed to define the core domains of integration for migrants and refugees resettling in a new country.

Figure 1: Ager & Strang Conceptual Framework for Refugee Integration (reprinted with permission).

Figure 1: Ager & Strang Conceptual Framework for Refugee Integration (reprinted with permission).

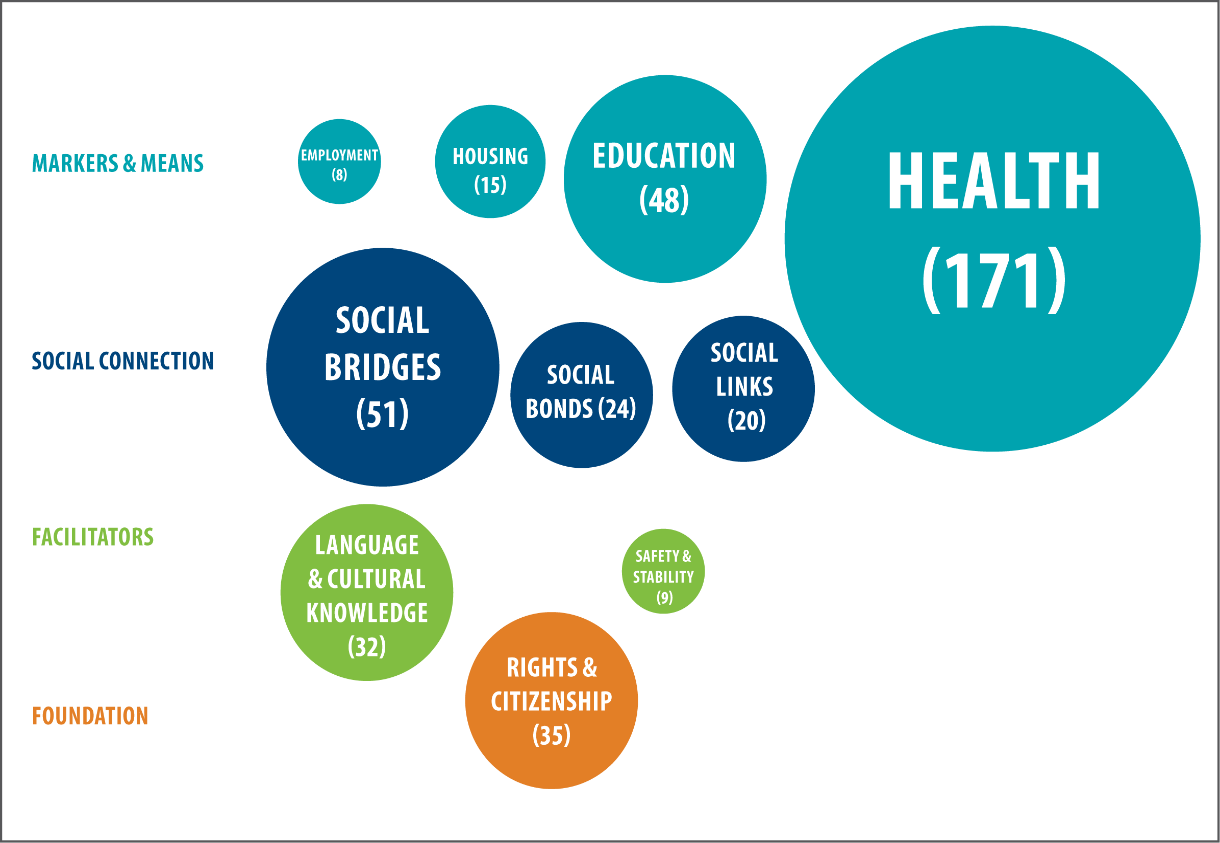

We used the framework to examine recovery-funded programs offered to youth in the four years after wildfires struck Victoria, Australia, in 2009—commonly known as the Black Saturday Bushfires (see Figure 2).

We reviewed the websites of relevant government departments and recovery agencies, as well as publicly available records of initiatives that target children, young people up to the age of 18, or parents and teachers. Our work showed that most of the programs were delivered one to two years after the fires and tended to focus on high school students, with a moderate amount for elementary school students, and very few for preschoolers.

To test the usefulness of the framework, we reviewed the relevance of each of the domains to post-disaster recovery for children and teenagers:

Change in employment options after disaster can alter family circumstances by influencing parent employment and directly affect teenagers seeking casual employment or entering the workforce. Loss of housing, temporary housing, and separate living arrangements for families (to enable one of the parents to maintain an income) are all common post-disaster and are likely important influences on youth development and well-being. However, neither employment nor housing were central in the delivery of services for children and youth after Black Saturday.

The role of education in disaster recovery was clear. Our recent research showed reduced academic progress for elementary school children attending bushfire-affected schools in Victoria. A separate review of recovery services showed that although many addressed education, they weren’t usually related to classroom activities but instead were out-of-school programs such as homework clubs and mobile libraries.

Physical injuries and ongoing mental health problems are key characteristics of post-disaster environments. Our review of children and youth services post-Black Saturday showed that the majority of services targeted health, predominantly consisting of individual mental health counseling.

The domains relating to social capital recognize the different relationships that are important in the lives of children and youth including the social bonds of family and close friends, the social bridges provided through wider social networks, and the social links with organizations that provide resources. Social bridges were strongly supported after Black Saturday, mainly through youth group activities.

Domains involving a sense of belonging and connection to culture are key to child and youth resilience. In a post-disaster context, we interpreted language as opportunities for creative expression to help children to process their emotional responses to the disaster experience. This was well-supported after Black Saturday with many youth art and music initiatives.

The loss of a sense of safety and stability was such a pervasive finding in our post-disaster research that we were pleased to see this domain in the framework. Unfortunately, very few of the recovery programs were specifically addressing safety and stability—a potentially critical oversight. There is developing evidence allowing children and youth to exercise their rights and citizenship by showing leadership and contributing to disaster recovery can have positive effects on their self-confidence, resilience, and independence. We were encouraged to see a relatively strong focus on opportunities for youth to demonstrate leadership and citizenship after Black Saturday. It is possible that these opportunities will contribute to a sense of safety and stability by increasing children’s competence and confidence in their ability to live in a risk environment. However, these mainly involved older youth.

Figure 2: Analysis of Post-Bushfire Recovery-Funded Services for Children and Teenagers Using the Ager & Strang Conceptual Framework (each circle is proportional to the number of programs—in parentheses—that address that domain).

Figure 2: Analysis of Post-Bushfire Recovery-Funded Services for Children and Teenagers Using the Ager & Strang Conceptual Framework (each circle is proportional to the number of programs—in parentheses—that address that domain).

So what does this tell us? First, that there are many different ways we can help children and teenagers to process and recover from disaster experiences. The Ager and Strang Framework is a helpful guide to identifying key areas of influence that might otherwise be overlooked. Second, we need to consider and accommodate all of the different ages and stages of childhood and youth when planning recovery services and, in particular, we should make sure the youngest ones have opportunities to support their recovery. And finally, there needs to be a focus on restoring a sense of safety and stability. This may be supported by teaching young people how to live in risky environments and giving them opportunities to contribute to resilience and recovery initiatives for themselves and their community.

We would like to acknowledge our co-authors of the original research article on which this piece is based—Elyse Baker (nee Snowdon), Hugh Colin Gallagher, Greg Ireton, David Forbes, and Elizabeth Waters.

Suggested Tools

Community Trauma Toolkit

Emerging Minds

Interactive toolkit of 166 different resources to support the social and emotional well-being of children who have experienced traumatic events.

For a list of all the tools included in this special collection, visit the Children and Disasters Tool Index.

Lisa Gibbs is director of the Jack Brockhoff Child Health & Wellbeing Program at the University of Melbourne and academic lead for Community Resilience and Public Health within the Centre for Disaster Management and Public Safety.