By Harri Raisio, Alisa Puustinen, and Vesa Valtonen

As disaster responses become more complex, there is a greater need to coordinate the activities of public authorities with business operators, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and citizen volunteers. To achieve the goal of improving disaster response, we recommend a process of “co-creation” where each of these groups is involved in planning disaster responses and the roles of each group are clearly defined. This approach allows public authorities to take advantage of the experiences, resources, and ideas of these diverse groups. In turn, it allows groups outside of traditional government response structures the opportunity to contribute.

The approach described here is being taken in Finland where it has been used to develop a comprehensive Security Strategy for Society. In response to this new approach, we organized eight regional forums involving a total of 188 people from the public sector and NGOs to discuss how co-creation occurs in planning safety and security functions and to discover what challenges are not being met.

Taking Steps Toward Security and Safety

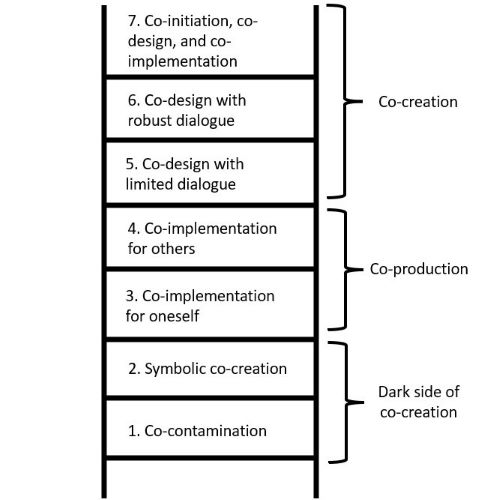

The Ladder of Co-Creation, adapted based on work by Torfing, Sørensen, and Røiseland

The Ladder of Co-Creation, adapted based on work by Torfing, Sørensen, and Røiseland

We use a model developed by Torfing, Sørensen, and Røiseland called the Ladder of Co-Creation to provide a framework for our findings. This is a highly useful model, but Torfing and colleagues’ ladder does not address the negative aspects of co-creation. Therefore, we added a rung to the beginning of the ladder to account for what we refer to as co-contamination, which is anything that is added to the co-creation process that is harmful or undesirable. Co-contamination can occur, for example, between spontaneous volunteers and established professional emergency management agencies. These different groups may have competing priorities or conflicting ideologies that stymie collaborative processes. We added a second rung for co-creation processes that are symbolic and do not actually consider the input of citizen groups.

We next turn to the widely used concept of co-production, which is understood as a limited case of co-creation, highlighting the aspect of co-implementation. Thus, the third step on the ladder involves empowering citizens to enhance their own capacities to respond to disasters. Enhancing one’s capacity to respond to disaster simultaneously encourages co-implementation for oneself. This can take the form of developing family emergency plans, having a home emergency supply kit, and individuals taking part in training programs such as first aid courses. Of course, these “individual action” can have strong co-benefits for families and even entire communities.

This leads to the fourth rung of the ladder, co-implementation for others, which entails creating value for others by performing volunteer work carried out in cooperation with public authorities. Some examples of this are volunteer firefighter organizations or the Red Cross and Red Crescent organizations.

The fifth rung occurs when these groups or individuals provide input in designing new tasks and solutions. This takes place in co-design processes with limited dialogue. Examples include: focus groups, interviews, written consultations, and public hearings.

While the fifth level is limited in its dialogue, being at its worst only one-way communication—public actors wanting to obtain feedback from citizens and other stakeholders—the highest rungs on the ladder aim for genuine two-way communication where joint solutions are sought. Co-creation begins with co-design processes with limited dialogue before evolving into co-design with robust dialogue, like deliberation. Examples include service design and deliberative security cafés.

On the final rung of the ladder, the approach is most comprehensive and can extend as far as joint agenda-setting and problem definition. In the spirit of collaborative innovation, variety of societal actors are then taking part in co-initiation, co-design, and co-implementation of safety and security services. An example of this stage is comprehensive safety and security clusters.

Issues with Co-Creating a Safer Society

Some problems revealed by our interviews were as simple as members of the public sector scheduling meetings and exercises at times when volunteers were at work making it difficult for them to participate in planning and training. Another problem is that public authorities are concentrated in urban population centers, which leaves people living in rural areas with a greater need for self-sufficiency. A third problem was that the bureaucracy and level of qualification needed to become a volunteer for some organizations may discourage people from participating.

The latter issue emerged with the Finnish Lifeboat Institution, a volunteer organization that has had a long-standing cooperative relationship with the Finnish Coast Guard. Volunteer qualifications were seen as being nearly that of a professional, which led to concern that people would not commit themselves to action in the long term. It is worth noting, though, that in other ways, the Finnish Lifeboat Institution provides a good model of how public authorities should interact with NGOs. The Coast Guard conducts regular training exercises and audits of the volunteers so that they know exactly what their capabilities are and how to use them in an emergency. Such training and working together was mentioned as the best way to create effective partnerships between public authorities, the volunteer sector, and the private sector.

The rise of social media also presented problems according to our research participants. “Pop-up volunteering” poses a logistical challenge for public authorities and NGOs. In some crises that received considerable media attention, groups of untrained volunteers would organize themselves on Facebook or another platform and show up to places where search operations were underway to form their own unofficial search parties. These volunteers’ goals sometimes ran counter to what emergency managers were trying to accomplish, and they ended up wasting time by searching areas that had already been covered or searching in a non-systematic fashion. This problem could be addressed by creating a “bridge” between spontaneous volunteers and emergency service agencies. This bridge would ideally provide a clear set of responsibilities that could be handled by spontaneous volunteers and a way to organize them to accomplish those tasks.

Moving Forward in Finland and Beyond

Further research is needed to understand the best way to make use of spontaneous volunteers. It would be worthwhile to investigate the options to include spontaneous volunteers in the co-creation process, preserving their innovation potential and adaptability, while also reducing their susceptibility to risk. The role of business operators was not part of this study, and more research is needed to fully understand how they may use their knowledge and resources to assist in emergency situations. We also suggest more research into the downsides of collaboration and co-creation, such as how co-contamination occurs and how that can be stopped or controlled. In the end, we are stronger when we work together, but we also must be smarter to achieve the best outcomes.

About the Special Collection

This special collection of Research Counts grew out of a longstanding collaboration between the International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters (IJMED) and the Natural Hazards Center. Our commitment in this special collection is to bring key findings and ideas from recent IJMED articles to a broader audience of emergency managers, disaster risk reduction professionals, and policy makers in the hazards and disaster field.

This Research Counts article was written by freelance science journalist and editor, Zach Zorich. It is based upon the following publication:

Raisio, Harri, Alisa Puustinen, and Vesa Valtonen. 2021. “Co-Creating Safety and Security?: Analyzing the Multifaceted Field of Co-Creation in Finland.” International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 39(2): 263-291.

Harri Raisio, PhD, is a university lecturer in social and health Management at the University of Vaasa and an adjunct professor at the University of Eastern Finland. His research has focused on complexity sciences, deliberative democracy, informal volunteerism, and crisis and disaster management.