Steps to a place where a home once stood in the Lower Ninth Ward. ©Lori Peek, 2013.

Steps to a place where a home once stood in the Lower Ninth Ward. ©Lori Peek, 2013.

By Kai Erikson

The hurricane that crashed into the Gulf Coast and the floodwaters that inundated most of New Orleans, both known as “Katrina,” were devastating events by any human standard, and it makes good sense to assume that they were the primary cause of the deep emotional suffering that followed. But it will be very important for those now trying to assess the amount of harm taking place in more recently damaged locations like Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico, to realize that this form of suffering is very likely to continue long after the winds subside and the waters recede. For many people, “recovery” will not be a steady climb out of misery as broken structures are repaired and broken spirits are attended to. It will be a long period of time during which new forms of traumatic reaction come to the surface. The initial strike, that is, transforms the social atmosphere in ways that bring about other sources of shock and anguish. Three examples:

First, it was a frequent finding in the years following Katrina that the recovery process itself became so frustrating and dispiriting for some survivors that it outranked the disaster itself as a source of real distress. When agencies like FEMA came to town to distribute funds to the urgently needy, for example, they often proceeded in a manner that simply bewildered the persons they had come to help. The ways of a federal bureaucracy came into contact with the ways of a severely damaged community, and each operated with a different sense of what constitutes reality, a different sense of how to relate to fellow human beings. The exchanges that followed could not reach across that wide abyss a good part of the time. Many thousands of desperate people simply gave up trying, and many thousand more had to settle for funds that did not even come close to reflecting what they had good reason to think they were entitled to. FEMA counted that as an inconvenience; survivors were more likely to count it as a grave source of traumatic injury.

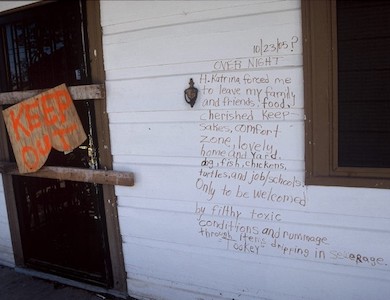

Second, it was a frequent finding in Katrina that survivors of the storm began to feel that they had lost a secure foothold in the setting they called home. That was obviously the case for people who were displaced by the storm and were not able to return home for long stretches of time, sometimes forever. But it was also the case for persons who did not move an inch from their original niche on the surface of the earth but came to feel that the land they occupied or the spaces surrounding it were no longer home-like. They, too, had become strangers in an unfamiliar landscape. That feeling can hurt to the very core, all the more so for persons who see themselves as belonging to – being an intimate part of – a particular place. In both cases, “uprooted” can be the right word for what happens in human life as it is in plant life: to be wrenched from one’s natural turf, in fact or in perception, is, almost literally, to wither.

Third, it was a frequent finding in Katrina that persons who encounter that kind of shock come to feel that they have been abandoned by the social order they thought they were members of. Their nation, their state, their city proved to be as indifferent and as heartless as the hurricane that attacked them without warning. That can be a truly terrifying realization: that they are now alone or part of a lonely cluster of people out on a barren plane where the supports they once thought they could count on – government, home town – no longer show any evidence of truly caring. This is a trauma that can continue for years, decades, lifetimes.

It does not help that what happens long after a storm event so often continues to be known by the code name assigned it by meteorologists long before the first hint of it even appears on the horizon: Katrina, Harvey, Irma, Jose, Maria. That familiar habit can hardly help but suggest that that the horrors inflicted by the storm itself are what really matter. Nor does it help that the clinical term we employ to identify the mental suffering that follows is PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The “Post” suggests that even the symptoms which appear long after the storm event itself are nonetheless a reaction to what happened then. And, in a way, it also suggests that recovery can be expected to begin as soon as the initial shock disappears. A number of psychiatrists, having learned that rates of PTSD remained as high years after Hurricane Katrina itself slipped back into history, described those symptoms “Delayed Onset Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.” Read carefully, that can only mean that reactions to the storm and the flooding had not really worked their way into human consciousness until a good deal later. But it makes far better sense to conclude that those symptoms are a product of the aftermaths rather than of the original blow.

House in the 8th Ward following Hurricane Katrina ©Steve Kroll-Smith, 2005.

And it is very important to keep in mind, too, that African-Americans as well as other minority populations are far more likely than their white compatriots to be susceptible to those forms of injury. The reasons for that are obvious on their face. Black persons – and we should probably add a “brown” to that color code so as to include the people of Puerto Rico – are more likely to live in poverty, to be more vulnerable to most of life’s misfortunes, to be dismissed by their white fellow citizens. But it has to be added to that cruel list that they are also far more likely to have been exposed to traumatic blows long before the appearance of a disaster – and for exactly those same reasons.

Footnote: Reports about the relative ineptness of FEMA and other federal agencies in the time of Katrina have been circulated widely and appear to have had some noticeable effect. Or so we must hope. But very little has been said about the process by which federal funds made their way through the market economy on their way to the persons they were meant to help. The evidence from Katrina, at least, strongly suggests that those funds passed from contractor to contractor to contractor – each station-stop on that journey taking a substantial share of the allocated funds. There are good reasons to suspect that the sums that actually reached the persons they were intended for were no more than a small portion of the original allocation. Several experienced observers who followed the siphoning-off of those rescue funds concluded that it was far and away the most egregious form of “looting” to result from Katrina. So individuals responsible for receiving federal funds in the damaged disaster sites and distributing them to the persons for whom they were intended should be advised to trace their path from Washington to Texas, Florida, and perhaps especially to Puerto Rico, with special care.

Kai Erikson is a William R. Kenan, Jr. professor emeritus of sociology and American studies at Yale University; former president of the American Sociological Association; chair of the Katrina Task Force, Social Science Research Council; series editor of "The Katrina Bookshelf," University of Texas Press; and fellow of the Natural Hazards Center.