By Elke Weesjes with Phil Nerges

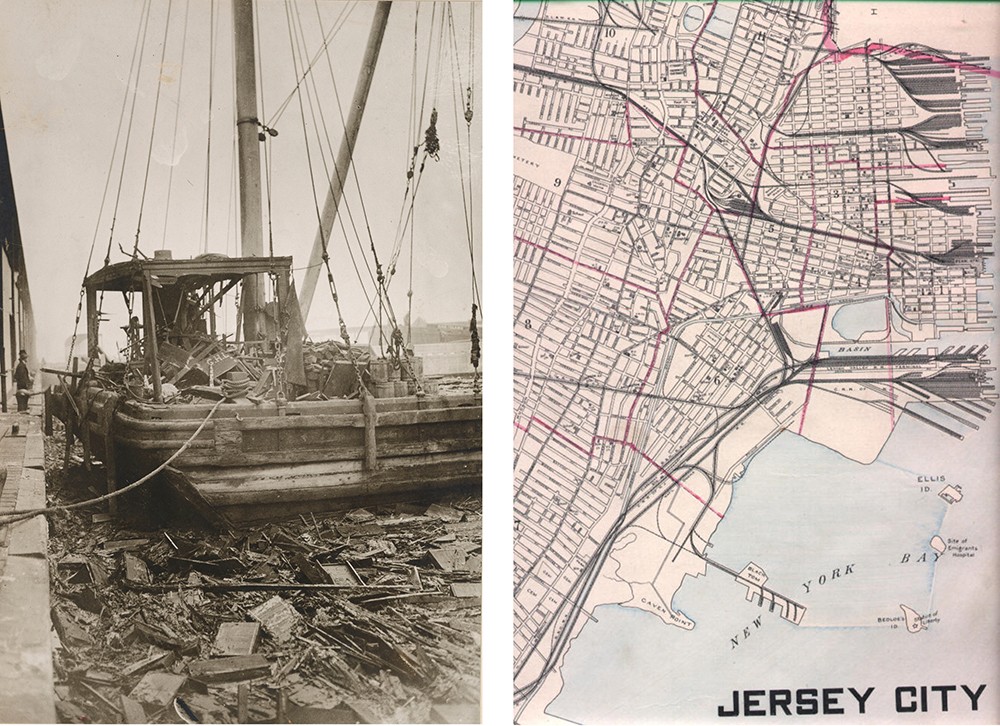

Wrecked munition barge and other ruins caused by explosion of munitions on Black Tom Island, New Jersey © National Archives.

JULY 30, 2016, marked the 100th anniversary of the Black Tom explosion in Jersey City, New Jersey. The violent blast, one of the largest explosions on U.S. soil, occurred on Black Tom Island, a peninsula jutting out into Upper New York Bay situated across from the Statue of Liberty. The explosion, which decimated nearby neighborhoods within a five-mile radius, was caused by a number of fires at the island’s munition depot, where barges and railroad freight cars were storing significant amounts of ammunition and dynamite to be sent to Entente powers in Europe.

The catastrophic incident was at first believed to be an accident. Local officials quickly blamed the Lehigh Valley Railroad, which owned the facility where the explosion occurred. However, three years later, after piecing together evidence that pointed at German sabotage, investigators concluded that that the explosion was not accidental after all (King 2011; Roberts 2016).

Some historians consider the explosion—measuring up to 5.5 on the Richter scale and, as such, 30 times more powerful than the collapse of the World Trade Center 85 years later—as the most destructive terrorist attack on U.S. soil until that fateful day in 2001 (King 2011; Roberts, 2016). Nevertheless, not many people have heard of the Black Tom explosion. Fewer events, however, have had a greater impact on the creation of federal agencies charged with national security.

L: Black Tom Explosion Jersey City © National Archives, 1916. R. Black Tom Island, lying off a Jersey City pier, Public Domain, 1912

At the time of the Black Tom blast, the United States was still officially neutral in World War I. There were no federal statutes that addressed peacetime spying or sabotage by foreign nations, nor were there any agencies that possessed the structure or resources to protect the country from attacks of that type. All of this changed after Black Tom. Laws related to spying and espionage were introduced; the most prominent being the Espionage Act of 1917. Furthermore, intelligence agencies, such as the Bureau of Investigation (later renamed Federal Bureau of Investigation) and the Secret Service, were restructured to combat the enemy within.

Today Americans—who live under the near-constant threat of terrorism—rely on these agencies and the laws implemented to stop foreign conspiracies.

Shop on Warren Street guarded by two police men. This is one of hundred of shops in Lower New York City which had its windows shattered by the explosion of a carload of dynamite and 100 carloads of ammuniction and shrapnel for the entente Allies. Policemen were placed on guard to prevent looting. © National Archives, 1916

War profiteering and German retaliation

The British Royal Navy blockaded German ports soon after World War I erupted in August 1914, shutting off not only war supplies, but also much needed food supplies for Germany and Austria. Exports from the United States to Great Britain, France, and Russia continued in spite of Germany’s objections. The commerce swiftly transformed the United States from debtor nation status to creditor nation. The transport sector and the steel and chemical industries prospered creating an economic boom that lasted through the war’s end (Witcover 1989).

On February 4, 1915, locked in a fight-to-the-death battle with the Entente powers, Germany launched unrestricted submarine warfare against all allied-bound vessels to stem the flow of munitions. It also started sabotage efforts on American soil.1 German agents placed small cigar-shaped firebombs on Europe bound vessels, intended to ignite after the ship departed port. A series of accidents at sea occurred, damaging munitions and other cargoes. However, without a national intelligence service, these acts were investigated separately by federal, state, and local authorities. Initially, none of these authorities had the power or the resources to make connections between these sabotage efforts and the perpetrators got away unscathed. As such, the United States’ neutrality was maintained and the public refrained from taking sides in the conflict (Warner 2007).

Public opinion in the United States on the war changed almost overnight in May 1915, when a German U-Boat off the coast of Ireland torpedoed the British passenger liner Lusitania.2 Of the 1,962 passengers, 1,198, including 128 American citizens, lost their lives. The brutal attack turned the American public against Germany and angered President Woodrow Wilson. Still, he refused to declare war on Germany.3 Instead, Wilson immediately contacted Secretary of State Robert Lansing to have the Secret Service—which until then was only concerned with combatting counterfeiting and protecting the president—investigate espionage in the United States. A few months later, in 1916, Lansing founded the Bureau of Secret Intelligence. The aforementioned secret service agents, who were tasked with the surveillance of German diplomatic personnel at the Germany Embassy and the German consulate office in New York City, were transferred to this new bureau (United States Department of State, 2011).

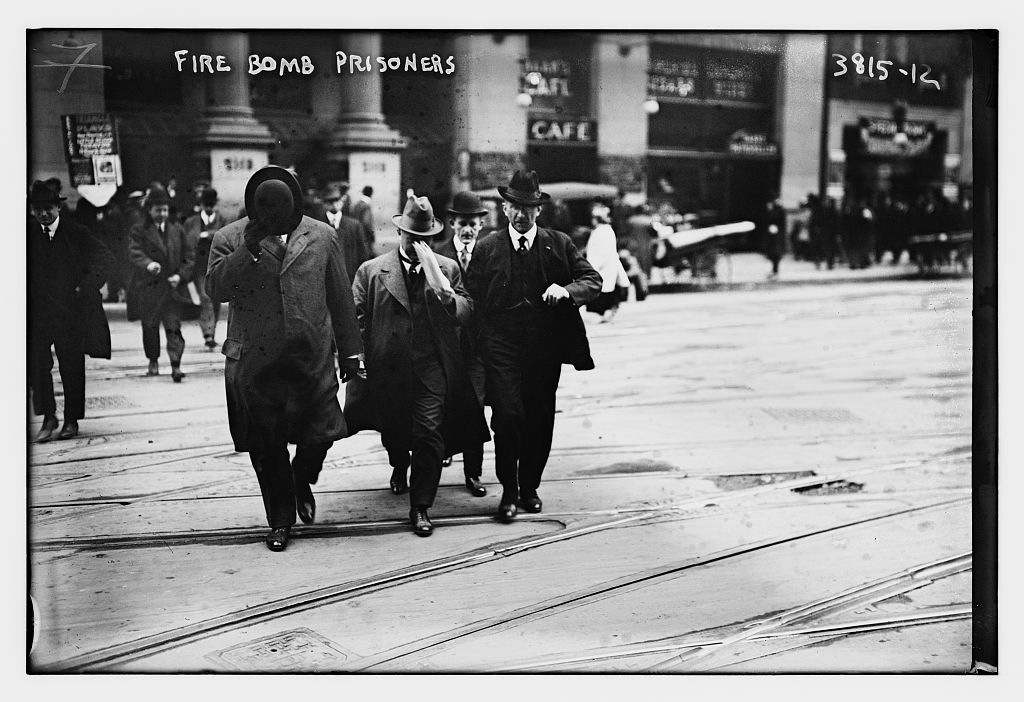

Bomb suspects indicted 1916 © National Archives, 1916

Furthermore, the New York Police Department Bomb Squad4, under leadership of New York City Police Department inspector Thomas J. Tunney, was also instructed to turn its focus on foreign agents. Not much later, in early 1916, the Squad rounded up a number of German saboteurs in New York and New Jersey. The arrest briefly halted the cigar bomb campaigns on ships, but the men in question were quickly replaced and the campaign restarted with vigor. In addition, a small team of German agents shifted their targets from ships carrying war materiel to munitions factories and storage depots.

Their attention focused on one of the largest ammunition stockpile outside of Europe, the National Dock and Storage facility on Black Tom Island. Surprisingly the site, a rail-to-ship terminal, was unfenced, easily accessible from land or water and virtually unguarded (Witcover 1989, Milman 2006).

The German agents tasked with infiltrating Black Tom recruited Michael Kristoff, a 23-year-old Austrian immigrant who worked for the Tidewater Oil Company in Bayonne, New Jersey, not far from Black Tom. Kristoff—a familiar face around Black Tom who would not have a problem walking past the guards—was described as slow-witted, gullible, and eager to stop the war. Because he could be easily controlled, along with his belief in the cause, Kristoff was exactly the person the agents needed for the job (Witcover 1989).

The night of the Black Tom explosion, nearly 70 railroad freight cars loaded with two million pounds of munitions were awaiting shipment to Europe. Nearby, a barge, the Johnson No. 17 contained 100,000 pounds of dynamite. Shortly after midnight, Kristoff, accompanied by two other more seasoned saboteurs named Kurt Jahnke and Lothar Witzke, placed explosives on the barge and freight cars. They then left the way they had arrived: Kristoff left by foot and the two other men by boat. It took about 20 minutes before the explosives went off and created a fire. By the time the Jersey City Fire Department pulled up at 1:20 a.m., the fire had developed into an inferno and the fire fighters were unable to get close enough to do anything. They stood by helplessly as more cars and vessels caught fire. At 2:08 a.m., the entire barge load of dynamite exploded and shook the surrounding area.

Canal boats amidst the wreckage caused by munitions explosion on Black Tom Island, New Jersey © National Archives, 1916

“The shock was so great that I was thrown off my chair into the hall and the broken glass fell in showers upon me as I lay on the floor,” Owen Fitzpatrick, a telephone operator who was working on Ellis Island that night, told The New York Times. “Four shells of three-inch caliber fell on the gravel path in front of the main door and another shell passed through the roof of the coals bunker attached to the power house” (The New York Times, July 31, 1916).

The first blast shattered windows of buildings in a five-mile radius, including nearly all buildings in Jersey City, and much of Brooklyn, Manhattan, Hoboken, and Bayonne. Another massive explosion followed at 2:40 a.m., raining shrapnel on the fire fighters who were still present at the site (Millman 2006). The explosions caused mayhem and panic throughout the New York City and Jersey City area.

Considering the sheer force of the blasts, fatalities were miraculously low: The official death toll held at five. However, according to Millman (2006), “there had been hundreds of people living on barges just northwest of Black Tom—immigrants, vagrants, and the poor—and that dozens of them surely should be counted among the dead.”

Property damage was catastrophic, totaling an estimated $20 million (Millman 2006), the equivalent of nearly $460 million today.

On September 2, 1916, Tunny, one of the few who suspected foul play, arrested Kristoff. Unfortunately he was unable to make the charges stick and was forced to let his main suspect go (The New York Times, July 6, 1921).

Accident or sabotage?

Just a few months before the Black Tom explosion, the NYC bomb squad arrested nine Germans who were charged with “conspiring to set on fire by means of incendiary bombs munitions ships playing between this port and Europe” (The New York Times, April 29, 1916). The subsequent trial made it clear that it was the group’s ingenious cylinder-shaped cigar bombs that were responsible for what had been—up to that point—considered mysterious fires and explosions that had occurred on merchant ships.5

In light of these developments, it might come as a surprise that only a few people thought the Black Tom explosion was an act of sabotage. Most thought it was just another accident. After all, it wasn’t the first time that human negligence caused a devastating blast.

In 1911, not far from Black Tom Island, a carelessly tossed cigarette caused a massive explosion while dockworkers were unloading explosives and detonating caps from a steamer at the Communipaw dock no. 7 in Jersey City Harbor. Ten people were killed and damages were estimated to be $250,000 (Report on Explosion at Communipaw, 1911).

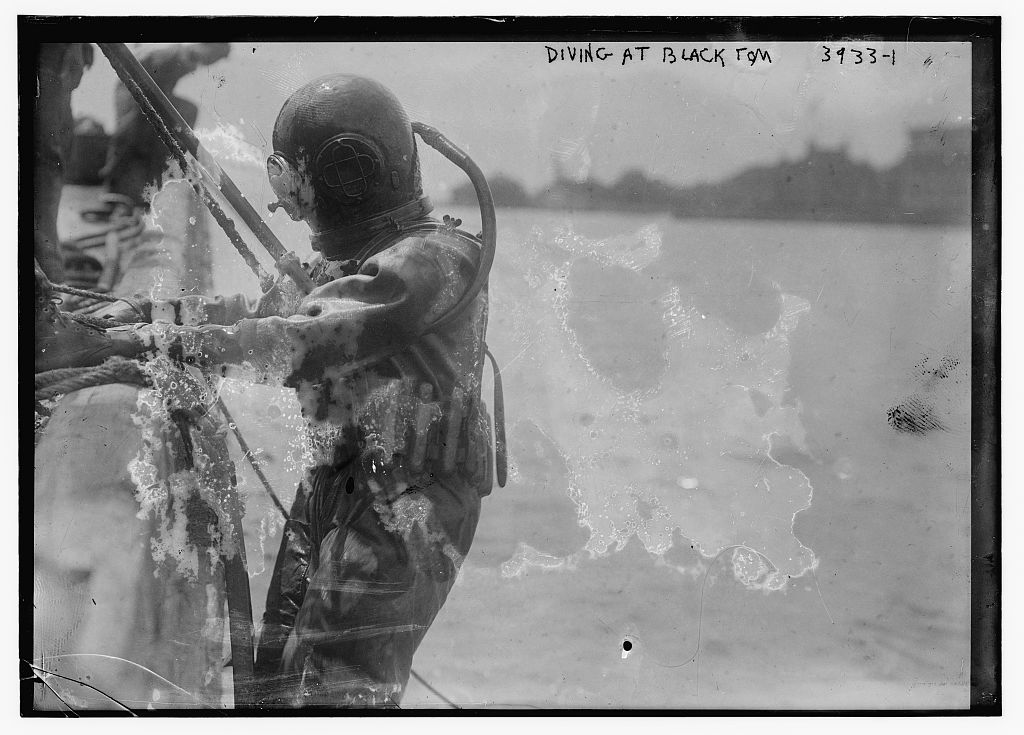

Diving for shells after the Black Tom explosion © National Archives, 1916

Assuming a similar act of carelessness led to the Black Tom explosion, local officials and the newspapers generally assigned responsibility to the Lehigh Valley Railroad, the National Dock and Storage Company, and the Interstate Commerce Commission, the governmental branch charged with the formulation of regulations for the safe transportation of explosives and other dangerous materials by land.6

After the Black Tom explosion journalists and residents questioned if these regulations could actually protect the public from catastrophe. Only days after the incident, a concerned President Wilson sent commissioner Edgar E. Clark of the Interstate Commerce Commission to New Jersey to conduct further investigations. In the subsequent report to the president, Clark declared that no evidence had been found of violation of Federal laws (The New York Times, August 5, 2016).

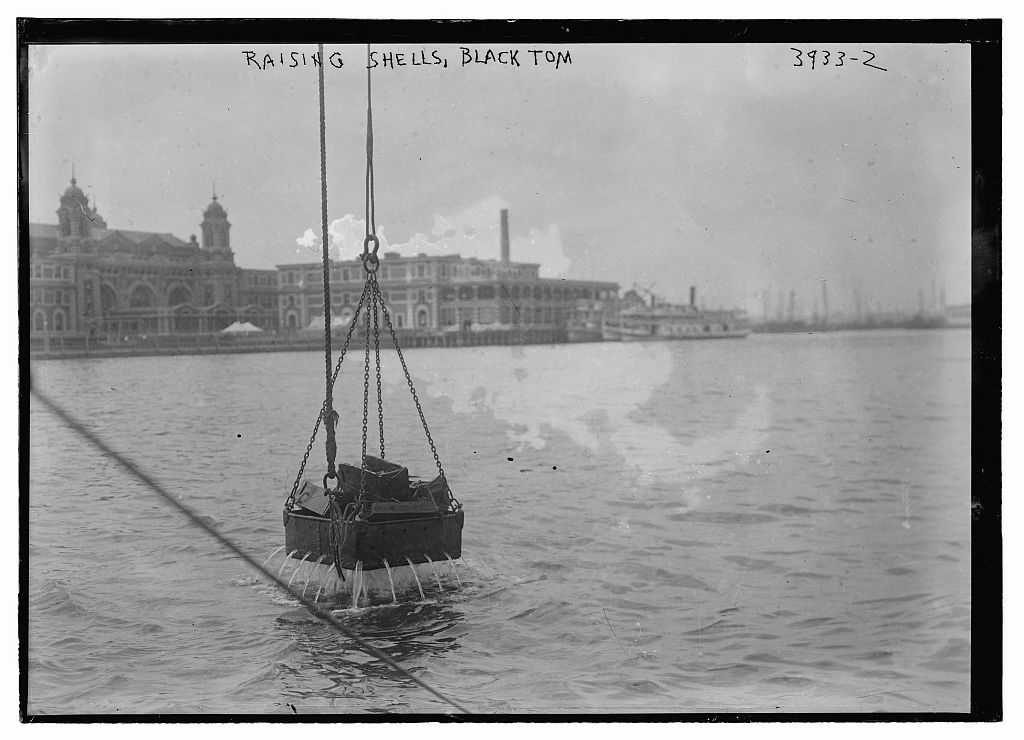

Raising shells after the Black Tom explosion © National Archive, 1916

In this context, it is important to recognize that the Interstate Commerce regulations only apply to the packing and safe transportation of explosives. Storage facilities, railroad yards and freight terminals had to follow state regulations7 (The New York Times, August 1, 1916). In the case of Black Tom, storage facility owners violated several regulations. For example, on the night of the explosion, loaded freight cars were in the railroad yard when they weren’t supposed to be.

Witcover (1989) writes that the workload was so backed up that it took up to a week before cargo was loaded from cars onto barges that in turn transferred their loads onto ships waiting offshore in the harbor.8 The parties in charge of the Johnson No. 17 barge also violated safety regulations. According to a 1922 report by the Atlantic Reporter9, “the barge had been moored to the pier for the purpose of taking on a load of explosives.” However, “before it was entirely loaded the workday had ended and the barge was left there until the following morning for the purpose of having the loading completed” (Atlantic Reporter, 1922). It was against the law to keep a loaded barge docked overnight (Witcover 1989).

Recovered shells after the Black Tom explosion © National Archives, 1916

Debating public safety

The Black Tom explosion ignited a short-lived public safety debate.10 Jersey City made a particularly bold move and attempted to stop all shipments of explosives in or from Jersey City (The Commercial and Financial Chronicle, August 5, 1916). The embargo, which was enacted on August 3, 1916, was lifted only a week later. The judge ruled that there can’t be two sources of power to regulate the same thing, according to The New York Times. He said that control of interstate commerce is vested exclusively in the Federal Government through its proper agent, the Interstate Commerce Commission.

In response, the Jersey City Public Safety Department agreed to obey the injunction and would not interfere in the passage of explosives through the city. However, Jersey City would prevent the storage of explosives in the city and would make sure that any shipments hauled into Jersey City were immediately transferred to ships in the harbor or to points outside the city limits (The New York Times, August 11, 1916).

While efforts like Jersey City’s are admirable, a fire at the Canadian Car and Foundry Company plant in Kingsland, a town located only a few miles northwest of Black Tom Island, showed that more systematic action was needed to keep the public safe.

After the outbreak of World War I, the Canadian Car and Foundry Company had secured major contracts with Russia and England for delivery of munitions, in particular artillery shells. To fulfill these contracts, the Montreal-based company built a large factory in New Jersey.

Kingsland, N.J. Munitions Plant Explosion. Photo shows the hill which is said to have been the only thing that saved the N.J. towns of Kinsland and Rutherford from probable destruction by exploding munitions from the ammunition factory which blew up. © National Archives 1917

Following the Black Tom Island explosion (while most thought it was an accident, there were some rumors the incident was caused by arson), the plant owners tightened security and constructed large fences. Unfortunately, these measures did not protect the plant from an inside sabotage job. The same German agents that recruited Kristoff ensured that Theodore Wozniak—a Pole from Austria who sympathized with the German cause—got a job on the factory line. On January 11, 1917, Wozniak started a fire while at work. The impact of his actions was disastrous: An estimated half-million artillery shells burst into the air as the fire swiftly spread through the plant. Fortunately the shells were not yet fitted with detonators, if they had, the shells would have exploded as soon as they hit the ground. Perhaps because of this, not one of the 1,400 workers was killed or seriously injured (Witcover 1989). The damage, however, was severe—estimated at $17 million (the equivalent of $320 million today). In addition, about 1,000 people in the town of Kingsland were forced to evacuate (The New York Times, January 12, 1917).

Similar to the Black Tom explosion, there was little speculation that the Kingsland fire might be the work of saboteurs. The New York Times reported it as an accident. Its headline read “No Hint of a Plot – Fire Believed to Have Started from a Spark.” The investigation that followed quickly pointed at Wozniak, but he claimed it was an accident11 and it was difficult to prove otherwise.

While the public didn’t seem too concerned about the cause of the two incidents, the NYC Bomb Squad continued its own investigation. Kristoff was arrested in relation to Black Tom but like Wozniak subsequently released because of a lack of evidence. Tunney, who led the Squad, was convinced that Black Tom and Kingsland were more than just accidents, and he was determined to find more evidence to prove sabotage (Millman 2006).

Kingsland was not the only munition plant destroyed by a mysterious fire. According to Warner (2007), between early 1915 and spring 1917, 43 U.S. munition factories suffered explosions or fires of mysterious origins, including the Hercules Powder Plant in Eddystone Pennsylvania. The plant went up in flames just three months after the Kingsland fire, killing more than 100 workers, mostly women and children.

Kingsland, New Jersey, Explosion. Wretched kitchen of the Lackawanna Hotel, Kingsland, N.J. The havoc was caused by the great explosion which occured at the Canadian Car and Foundry plant at Kingsland. The photo shows a hole made by a shell in the wall of the kitchen.© National Archives, 1917

Wilson gives in

The intensified U-boat campaign had already poised U.S. public opinion against Germany, but the final straw that even Wilson the champion of neutrality could not ignore came in the form of a telegram that was sent by Foreign Secretary of the German Empire Arthur Zimmermann on January 11, 1917. The so-called Zimmerman Telegram—in which the German Foreign Office promised Mexico its lost territory in Texas and the Southwest if it would attack America —was intercepted and decoded by British Intelligence (Witcover 1989).

Unable to maintain his neutral stance any longer, President Wilson instructed Congress to declare war on Germany on April 2, 1917. This decision accelerated the organization of the country’s counterintelligence agencies. Immediately after the declaration of war, the Attorney General instructed the roughly 400 agents within the Bureau of Investigation12 to focus on espionage and acts of sabotage. The U.S. army followed suit by increasing its small Military Intelligence Division; it hired detectives from the NYPD Bomb Squad (Warner 2006).

Only weeks later, on June 15, a major piece of legislation that remains the basis of modern espionage statutes was passed--the Espionage Act. This act made it a federal crime, punishable by death or life imprisonment, to “convey information with the intent to interfere with the operation or success of the armed forces of the United States or to promote the success.” The Sedition Act, a set of amendments to the Espionage Act, was passed in May 1918. The latter act made it a federal crime to “willfully urge, incite, or advocate any curtailment of the production of materials necessary for the war effort” (Dixon 2016).

The passage of these two acts seems to have abruptly quelled debate over public safety that followed the Black Tom explosion. A plausible explanation is that under these acts protests, such as obstructing freight trains containing munitions from running through a city, became a federal crime. Also, patriotism most likely trumped public safety. Rather than worrying about the safety of residents living in the vicinity of munition plants and storage facilities, Americans shifted their focus to their boys and brothers fighting in Europe.

Justice served (eventually)

After the war, the investigation into Black Tom and Kingsland continued. The NYPD and local New Jersey Police departments assisted by federal agents, focused primarily on Michael Kristoff, who had told two witnesses that he was involved in the Black Tom explosion. As mentioned before, Kristoff was arrested but released for lack of evidence. He disappeared and reappeared twice. In both cases he resurfaced because he was arrested for larceny. Police officers attempted to get more answers out of him about Black Tom, but Kristoff would not talk. He eventually died of tuberculosis and was buried in a local potter’s field. Similarly detectives were unsuccessful gathering other evidence that would attest Lothar Witzke and Kurt Jahnke’s involvement. In fact, they had a hard time proving anything: All they had were testimonies by unreliable witnesses and circumstantial evidence (Witcover 1989).

In the aftermath of World War I, a peace treaty between the U.S. and German governments was signed in Berlin on August 25, 1921.13 One of the treaty’s provisions was the creation of a bilateral commission governing claims of the United States and its nationals against Germany arising out of the war. This so-called Mixed Claims Commission blew new life into the unsolved cases of Black Tom and Kingsland. Unfortunately, whereas most other claims were quickly resolved, the ones related to Black Tom and Kingsland remained open because they warranted evidence that could prove the allegations of sabotage and German complicity.

It would take another 18 years of exhaustive investigations by more than 40 insurance companies, countless detectives, and a small army of lawyers before the Mixed Claims Commission was finally convinced that the incidents on Black Tom Island and at Kingsland were indeed caused by acts of German sabotage. On October 30, 1939, the Commission decided that Germany had to pay up. But that was not the end of it (Witcover 1989). As World War II raged through Europe, the court fight about the awards money dragged on. It wasn’t until February 1953, after Kristoff, Jahnke, and Witzke were long dead, when, during a postwar conference in London, the United States and Germany reached an agreement that the German government would pay $97,500,00 in awards to the victims of acts of sabotage. This number included $50 million to plaintiffs in the Black Tom explosion. The final installment was completed in 1979 (The New York Times, February 27, 1953).

Legacy

The attack on Black Tom Island and other acts of German sabotage, such as the Kingsland fire, were devastating. But they also left a positive legacy. Notably, they informed the much-needed creation of domestic intelligence agencies. By the time World War II started, the United States had a well-trained corps of agents to fight the enemy within, the Secret Service was a major intelligence force, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation was the lead agency for investigating and preventing acts of domestic and international terrorism.

The impact of Black Tom on public safety legislation was less apparent, but still a factor. Without the public safety concerns raised by the incident, much of the work of untangling overlapping laws and jurisdictions—and determining exactly which governments are responsible for American's wellbeing—would have been delayed.

The recent terrorist attacks in the United States are a good opportunity to pause and remember the Black Tom explosion and its legacy. Today more than ever, terrorists are testing the national security framework that was created in the explosion’s aftermath. The United States has gotten safer in the past 100 years, yet some issues—such as the tension between national security, public safety, freedom of speech, and the rights of citizens to question government and industry activities—remain relevant as ever. The United States continues to be trapped in a vicious cycle of terrorism and heavy handed counter terrorism.

Acknowledgement: The author would like to thank Phil Nerges a self-taught historian and author, who has done some of the preliminary research this article is based on. His insights and comments throughout the writing process were particularly appreciated.

References

Dixon, Pam (ed) 2016. Surveillance in America: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, and the Law, vol 1. ABC-CLIO.

King, Gilbert, 2011. “Sabotage in New York Harbor” Smithsonian, November 1, 2011. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/sabotage-in-new-york-harbor-123968672/?no-ist (accessed on October 26, 2016).

Millman, Chad. 2006. The Detonators: The Secret Ploy to Destroy America and an Epic Hunt for Justice. Little, Brown and Company, New York.

Report on Explosion at Communipaw, N.J., February 1, 1911, Bureau for the Safe Transportation of Explosives.

Roberts, Sam, “An Attack That Turned Out to Be German Terrorism Has a Modest Legacy 100 Years Later” The New York Times, July 24, 2016.

The Atlantic Reporter, Volume 117, Permanent Edition. June 15-September 14, 1922. St. Paul West Publishing Company, St. Paul, Minnesota.

The Commercial and Financial Chronicle, “The Munition Explosion In New York Bay” Volume 103, August 5, 1916, Page 451.

The New York Times, “German Debt Pacts To Be Signed Today” February 27, 1953.

The New York Times, “Seized as Suspect in Black Tom Case” July 6, 1921.

The New York Times, "Many Explosions Since War Began" July 31, 1916.

The New York Times, “Exploding Shells Rain Four Hours” January 12, 1917.

The New York Times, “Clark to Fix Blame for Big Explosion; Wilson Sends Commerce Commissioner Here to Continue Investigation” August 5, 1916.

The New York Times, “Explosives Laws Need Untangling” August 1, 1916.

The New York Times, “Ellis Island Like War-Swept Town; Damage Estimated at $75,000” July 31, 1916.

The New York Times, “A Railroad Car of Explosives Every 50 Miles,” July 2, 1916.

The New York Times, “Nine are Indicted in Ship Bomb Plots,” April, 1916.

U.S. Interstate Commerce Commission, Regulations for the Transportation of Explosives and Other Dangerous Aticles by Freight, prescribed under act of March 4, 1909. Revision formulated and published Jan. 1, 1912. Washington, D.C.

United States Department of State. 2011. History of Diplomatic Security of the United States Department of State. www.state.gov/documents/organizations/176705.pdf. (accessed on September 16, 2016).

Warner, Michael. 2007. “The Kaiser Sows Destruction – Protecting the Homeland the First Time Around” Central Intelligence Agency, April 14, 2007.

Witcover, Jules. 1989. Sabotage at Black Tom: Imperial Germany's Secret in America, 1914-1917, Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

-

In 1914, the German government gave Count von Bernstorff, the German ambassador in Washington, $150 million to limit the shipment of munitions to the British and the French. Since munitions couldn’t be transported safely to German ports, this money was largely invested in sabotage operations. Hiding behind his diplomatic role, Von Bernstorff became Germany’s chief of espionage and sabotage in the Western Hemisphere (Witcover 1989). ↩

-

In 1915, the British (much to the United States’ discontent) put foodstuffs on its contraband list and subsequently seized the cargo of the S.S. Wilhelmina, an American ship carrying a cargo of foodstuffs to Hamburg. In retaliation, the German admiralty declared a “war zone” around the British Isles in which “any enemy merchant vessel found would be sunk by the new and terrible weapon, the armed submarine” (Witcover 1989). The Lusitania, on her way from New York to Liverpool, was torpedoed on the day she was scheduled to arrive. ↩

-

President Wilson was adamant to maintain neutrality. Even when the public opinion turned against Germany after the attack on the Lusitania, Wilson continued to see nonintervention and nonbelligerency as essential to his role as the world’s peacemaker. This stance is underlined by the slogan he used during the 1916 elections, “He Kept Us Out of the War.”(Witcover 1989). The New York City Bomb Squad was created in 1905 to deal with anarchist and immigrant crime groups that operated in New York (Witcover 1989). ↩

-

The New York City Bomb Squad was created in 1905 to deal with anarchist and immigrant crime groups that operated in New York (Witcover 1989). ↩

-

The biggest breakthrough in the investigation of the mysterious fires on merchant vessels came when a British Captain of the S.S. Kirk Oswald, found the unexploded bombs on board after traveling from Brooklyn, NY to Marseille. Because the route of the ship was changed last minute, it had arrived at its destination before the devices could explode (Witcover 1989). ↩

-

On May 30, 1908, a federal law entitled An Act to Promote the Safe Transportation in Interstate Commerce of Explosives and other Dangerous Articles and to Provide Penalties for its Violation went into effect. The regulations that were formulated by the Interstate Commerce Commission became effective in October of that same year (U.S. Interstate Commerce Commission, 1909). The Bureau of Explosives was employed by the Commission to make regular inspections, conduct investigations, and confer with manufacturers and shippers to ensure these regulations weren’t violated (The New York Times, July 2, 1916). ↩

-

During the safety debate that followed the Black Tom explosion the New York Times revealed that down to the shore line the regulations were “many and minute” designed to cover every phase of the movement of explosives. Yet once this dangerous freight is loaded from the pier on lighters, the authority of the Interstate Commission and the State comes to an end (The New York Times, August 1, 1916). ↩

-

The intensification of the German U-boat campaign had slowed down the actual transport, but the demand for munitions was greater than ever. As a result freight bottlenecks such as the one at Black Tom occurred. ↩

-

The Atlantic Reporter is a regional case law reporter. ↩

-

Several initiatives addressed improving public safety, however, it is unclear which were successful. While newspaper articles discuss short-term embargoes, the introduction of tighter laws, and other efforts, long-term analysis is lacking and more research is required. ↩

-

German agents had paid two Italian factory workers to testify sparks came off the machine Wozniak was operating (Millman 2006). ↩

-

The Bureau of Investigation was established in 1908. At the time there were few federal crimes and it focused primarily on violations of laws involving national banking, bankruptcy, naturalization, and land fraud (FBI 2016). ↩

-

The reason for this separate peace treaty was the fact that the U.S. Senate did not ratify the treaty of Versailles. ↩

Elke Weesjes Sabella is former editor of the Natural Hazards Observer. She joined the staff in December 2014 after a brief stint as a correspondent for a United Nations nonprofit. Under her leadership, the Observer was revamped to a more visual format and one that included national and international perspectives on threats facing the world. Weesjes was the editor of the peer-reviewed bimonthly publication United Academics Journal of Social Sciences from 2010 to 2013.

Weesjes Sabella also worked as a research associate for the Center for Disaster and Risk Analysis, formerly located at Colorado State University (although no longer active). In that role, she collected and analyzed data and translated research findings for a broader audience. She played a central role in finalizing the Disaster Preparedness among Childcare Providers in Colorado project, which examines all-hazards preparedness in daycares and in-home childcare across Colorado. She co-authored the report based on the first stage of the project, which was funded by Region VIII of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Weesjes Sabella specializes in cultural memory and neighborhood/community change in times of acute and chronic stress. She has published articles on the impact of drought on farming communities in Kansas, the effects of Superstorm Sandy in Far Rockaway, Queens, urban renewal in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, and health services for vulnerable populations in the South Bronx.

Weesjes Sabella received her PhD from the University of Sussex. Her dissertation, Children of the Red Flag: Growing up in a Communist Family During the Cold War (2012), as well as the majority of her publication record, share the common methodology of understanding culture and identity through oral history.