PBS – The American Experience

PBS – The American Experience

Produced by: Amanda Pollak

Release Date: February 2015

Run Time: 60 min.

By Elke Weesjes

This fascinating documentary is loosely based on American author and journalist Timothy Egan’s acclaimed 2009 book The Big Burn – Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America and explores the history of the U.S. Forest Service and its response to the Great Fire of 1910.

The Great Fire, commonly referred to as the Big Burn, was a firestorm that burned more than three million acres of land in northeast Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana. It took the lives of 87 people, including 78 firefighters, incinerated seven towns in Idaho and Montana, and destroyed parts of ten National Forests.

Whether the Great Fire has sparked policies that benefit or further damage forest health has been the subject of intense debate. According to Egan, the fire did both. He argues, in his book and in the documentary, that the inferno strengthened the Forest Service (founded in 1905) and served as an impetus for the forest protection movement, which President Theodore Roosevelt started. In the long run, however, the policies introduced following the Great Fire of 1910 proved to be detrimental for forest ecology and caused bigger and more powerful fires. The Big Burn examines both the short-term as well as the long-term impacts of these policies.

The birth of the U.S. Forest Service

When President Theodore Roosevelt came into power in 1901 he was especially concerned with the conservation of the nation’s forests, a passion shared by his close friend Gifford Pinchot, a dedicated forester and politician. Until that moment the United States government had encouraged the development of open spaces, harvesting timber, industrial mining, and the creation of railroads. Unfortunately, all of this industrial progress had detrimental effects on the country’s forests. So much so that Roosevelt and Pinchot were worried that several species of trees would become extinct if they did not act quickly, according to environmental historian Steven Pyne.

“Timber was really a critical industrial product, and we were going to run out, much like an oil crisis in present times,” says Pyne in the PBS documentary. “So the solution was to regulate this unsettled land as a public domain that would then be governed by scientific informed bureaus, and this would allow us to conserve it. Not lock it up, but use it in some kind of rational regulated way.”

To this effect, the United States Forest Service was created in 1905 much to the discontent of timber and mining magnates, many of whom had seats in Congress and made it their personal mission to slash the agency’s budget and staff whenever possible.

Pinchot was named the Forest Service’s first Chief and was in charge of an astonishing 200 million acres of forestland divided between ten regions.1 He subsequently hired rangers for each of these regions. His first hire was William Greeley, who was asked to oversee the Northern Region; nearly 30 million acres, covering Montana, Northern Idaho, North Dakota, Northwestern South Dakota, Northeast Washington, and Northwest Wyoming. In turn, Greeley oversaw 160 rangers who would each be responsible for almost 300 square miles of National Forest.

Their duties were apparently more than just a job. “[These rangers] called what they were doing ‘The Great Crusade.’ In some ways, it was a religious crusade to them. They were doing God’s work to preserve the earth,” Egan notes in the documentary.

The Great Fire

These passionate and energetic rangers soon found out that the mission they felt so strongly about wasn’t very popular with the locals they encountered in their regions. After all, “forest rangers were standing in between the frontier mentality and the resource, standing in between what the frontier wants for the moment, and what Gifford Pinchot believes the country needs for the future,” says environmental historian Alfred Runte.

While the two camps did not agree on much, there was one common foe—fire.

Fire was particularly feared in those Western mining and ranching towns dotted along the transcontinental railroad. Steam locomotives passing through these wooden towns and surrounding timbered areas caused a significant number of fires each year.2

Considering the sheer size of the area they were responsible for, Forest Service rangers were not equipped to cope with these fires. Sometimes it would take days before they came across a wildfire and even then they would not know what to do. The art of firefighting was only in its infancy, says Pyne. “[In case of a fire] you were building what we would call a fire line now. You’re cutting a path clearing it of all debris. Some parts say three or four feet would be completely down to mineral soil so no fire could cross. This is just brutal grunt labor.”

When a violent electrical storm ignited hundreds of fires in a drought-stricken northern region in July 1910, desperate rangers under Greeley’s leadership applied this laborious method to control the inferno. Ed Pulaski, one of The Big Burn’s heroes, had joined the Forest Service in 1908. Together with another 159 rangers he was in charge of the disaster stricken region. Aware of their limited workforce, the Service quickly hired an army of mostly immigrants to help rangers fight the fire. Untrained, underpaid, and only equipped with some basic hand tools, many of these newcomers suffered terrible injuries. Others quit or mutinied, leaving the Service desperate for more manpower.

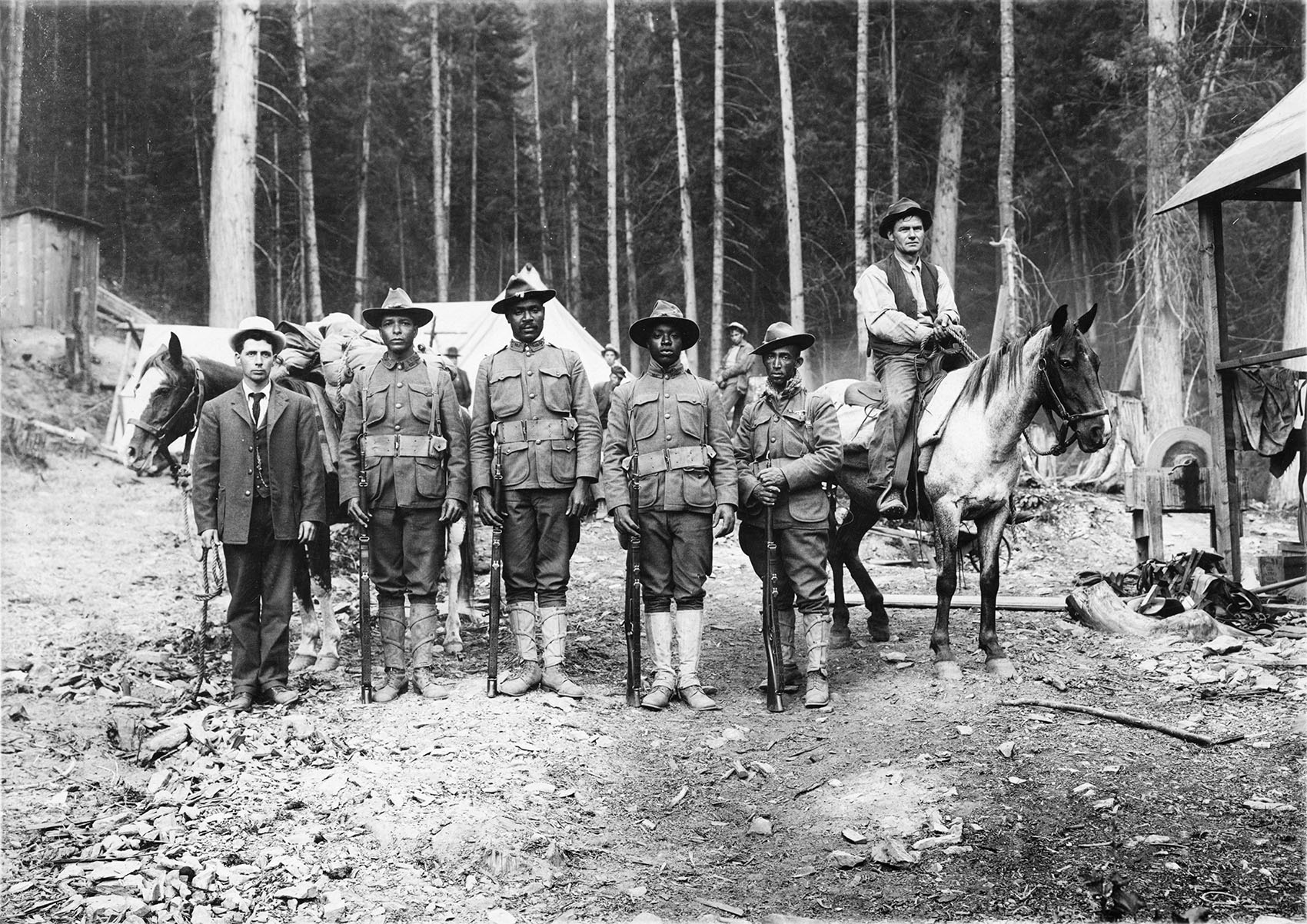

Seven companies of Buffalo Soldiers, the first African-Americans to serve as peacetime soldiers, heroically tackled and helped contain the Big Burn. © The Museum of North Idaho

By early August the fire was still spreading. President Taft who succeeded Roosevelt in 1908, sent 4,000 troops to the Rockies, including the 25th Infantry Regiment, also known as the Buffalo Soldiers—the first peacetime all-black regiments in the regular U.S. Army. Although there to help, these black soldiers were initially met with hostility in Idaho, according to Egan. “This is the first time they were ever sent to fight a fire. And they are sent to a very white area, almost doubling the black population of the state of Idaho. And so when this all black platoon comes and sets up camp, people scoff at ‘em, people say racist things about them. The newspapers say they play cards and drink all night. They say, ‘What can a black man know about possibly fighting a fire?’”

As it turned out, they knew a lot. While sudden hurricane-force winds of 70 miles an hour merged the flames of thousands of fires into one Big Burn, the Buffalo Soldiers evacuated Wallace, Idaho, a town that was encircled by fire.3 Some 30 miles up the road, in Avery, these brave soldiers started a number of backfires that saved the town from being burned.

While the Buffalo soldiers were evacuating Wallace, Pulaski, accompanied by 44 men, found himself face to face with a firestorm in the hills surrounding Wallace. He kept his cool and led his men to an old mining shaft where they sat out storm. Horribly disfigured but still alive Pulaski was able to bring 39 of his men to safety.

Other firefighters weren’t as lucky. In total, 79 firefighters lost their lives.

From fire suppression to fire management

The inferno was finally extinguished late August by an early season snowstorm. Once the atmosphere cleared, the scope of the devastation became apparent. Three million acres were burned and an estimated one billion dollars worth of timber had been lost.

The stories of the Big Burn’s heroes, the firefighters, the forest rangers, and the Buffalo Soldiers, were published in all the national newspapers, galvanizing support for the Forest Service and National Forests. Even a previously reluctant Congress changed its tune and gave the Forest Service the resources it needed. It doubled its budget and eventually created National Forests in the East.

Thoroughly shocked by the destruction of the fire, Pinchot and his successor, William Greeley (1911), after him became obsessed with putting out fires. They made it the Forest Service’s number one priority. This focus on fire suppression was further cemented when the so-called 10 AM Policy. Introduced in 1935, the policy t stipulated that fires must be contained and controlled by 10 o’clock the next morning.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that scientists began to realize that fires are needed to maintain a healthy forest ecology. Fires are a natural way for a forest to rid itself of dead or dying plant matter. It replenishes the soil and opens up space for new plants and trees to grow. In addition, there are many plant species in fire-affected environments that need fire in order to germinate or reproduce. Fire suppression eliminates these species and the animals that depend on them. These findings encouraged the Forest Service to abandon its 10 AM policy in 1978 and shift its focus from fire suppression to fire management. Rangers began to use fire to thin out potential fuel sources to prevent another Great Fire.

However, the ecological effects of the policies implemented after the Great Fire of 1910 couldn’t be undone. More than half a century of fire obstruction has left the country’s national forests more vulnerable to wildfire. Indeed, the Forest Service’s fire-suppression policies allowed a fuel buildup that renders today’s fires more powerful and difficult to control.

Yet without the Service there might not have been a forest at all, Egan argues.

“By putting out every fire . . . , they created indirectly, what are now some of the greatest wildfires. But imagine now, if this fire had not happened. They might have killed the Forest Service. And with it would’ve gone the idea that’s so embraced by a majority of Americans today, that we have more than 500 million acres that is all of ours, that belongs to each of us. By saving the fledgling idea of conservation, then only a few years old, this fire did save a larger part of America.”

A firefighter’s or U.S. Forest Ranger’s perspective could have enriched this documentary

The documentary, part of the PBS series American Experience, makes great use of archival images and footage. Like the book, the documentary focuses primarily on heroes: the dedicated rangers who risked their own lives to protect others. It also shines a light on the crucial role Buffalo Soldiers played in fighting the fire. The result is an exciting, educational, yet somewhat one-sided account of the Great Fire of 1910. The story is told by environmental historians, authors and journalists. While these are knowledgeable experts, a practitioner’s point of view is sorely missed. A firefighter’s or U.S. Forest Ranger’s perspective could have enriched this documentary.

References:

Gonzales, Ralph H. “An Introduction to Spark Arrestors” USDA Forest Service (http://www.fs.fed.us/eng/pubs/html/03511304/03511304.htm)

-

Today there are only 9 regions. Region 7 was eliminated in 1965 when the current Eastern Region was created from the former Eastern and North Central regions. ↩

-

Sparks, released by the engines, caused fires. To address this fire hazard legislation requiring spark arresters (mechanical device that traps or destroys hot exhaust particles expelled from an internal combustion engine) was passed in 1905 and applied to engines and boilers operated in, through, or near forest-, brush-, or grass-covered lands (Gonzales 2003). ↩

-

A third of Wallace was burned to the ground with an estimated $1 million (about $25 million today) in damage. ↩

Elke Weesjes Sabella is former editor of the Natural Hazards Observer. She joined the staff in December 2014 after a brief stint as a correspondent for a United Nations nonprofit. Under her leadership, the Observer was revamped to a more visual format and one that included national and international perspectives on threats facing the world. Weesjes was the editor of the peer-reviewed bimonthly publication United Academics Journal of Social Sciences from 2010 to 2013.

Weesjes Sabella also worked as a research associate for the Center for Disaster and Risk Analysis, formerly located at Colorado State University (although no longer active). In that role, she collected and analyzed data and translated research findings for a broader audience. She played a central role in finalizing the Disaster Preparedness among Childcare Providers in Colorado project, which examines all-hazards preparedness in daycares and in-home childcare across Colorado. She co-authored the report based on the first stage of the project, which was funded by Region VIII of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Weesjes Sabella specializes in cultural memory and neighborhood/community change in times of acute and chronic stress. She has published articles on the impact of drought on farming communities in Kansas, the effects of Superstorm Sandy in Far Rockaway, Queens, urban renewal in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, and health services for vulnerable populations in the South Bronx.

Weesjes Sabella received her PhD from the University of Sussex. Her dissertation, Children of the Red Flag: Growing up in a Communist Family During the Cold War (2012), as well as the majority of her publication record, share the common methodology of understanding culture and identity through oral history.