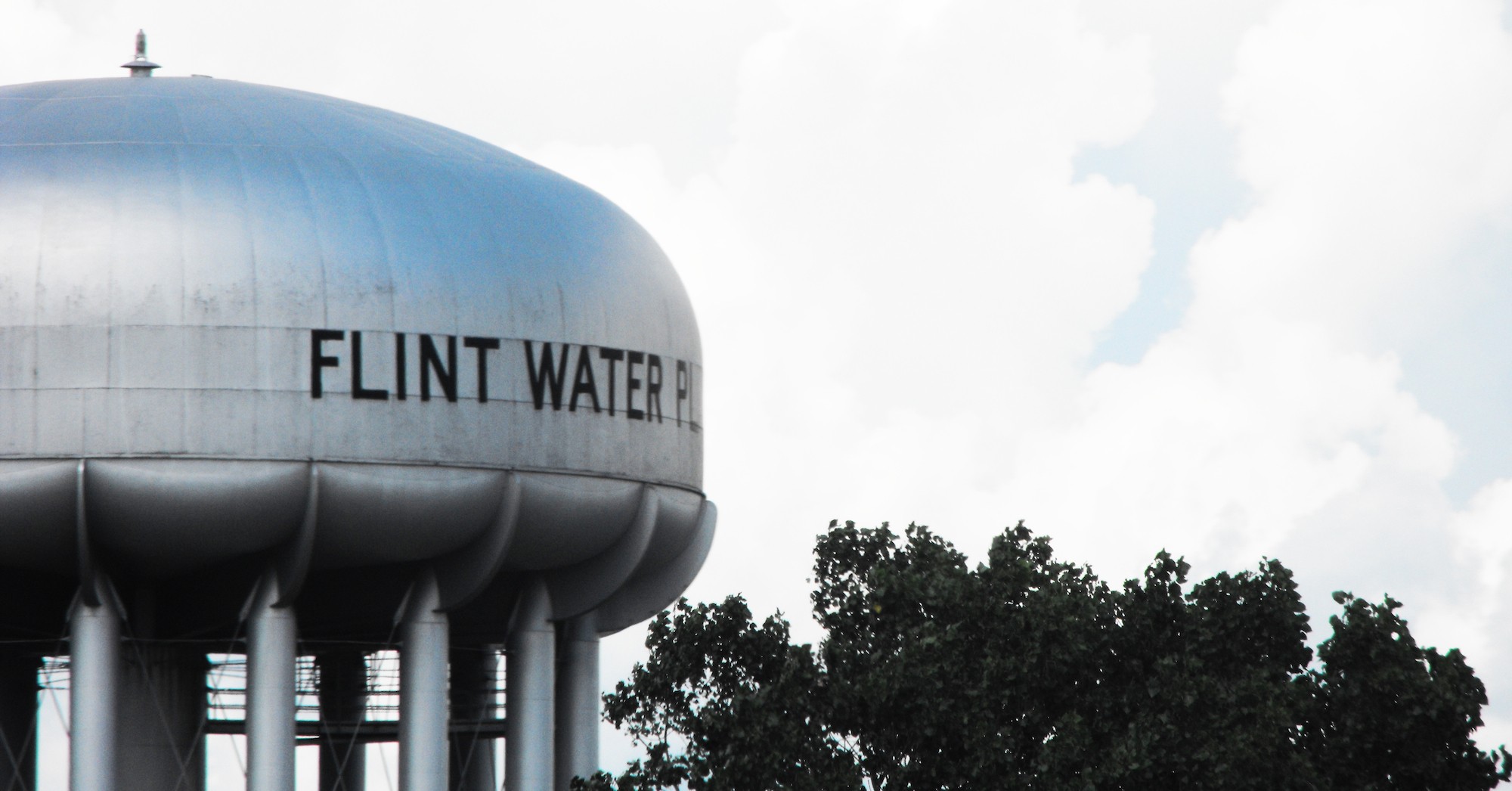

Flint Water Plant © Ben Gordon

THE TRAVESTY IN FLINT, Mich. has served as a flashpoint for highlighting failed government responses in the wake of disastrous circumstances. Former FEMA head Michael Brown harkened back to Katrina, suggesting the government should have applied lessons learned from that hurricane to the water-contamination crisis in Flint (Young, 2016). Michigan Governor Rick Snyder has even admitted that the mishandling of the crisis in Flint constitutes “his Katrina” (Fournier, 2016). The lack of ability to apply critical response lessons from Hurricane Katrina to the Flint crisis is troubling. The shocking mix of mishandlings and cover-ups that followed is also alarming, as citizens around the country must wonder if their community is the next Flint. Beyond that, the crisis highlights the extent to which disparate vulnerabilities to risk and disproportionate impacts of hazards can become issues of environmental injustice. In its wake, other incidents of technological accidents and environmental hazards have gained visibility. As such, questions about influences on government preparedness, accountability, and response become critical for redressing current crises and preventing similar ones in the future.

With all eyes on Flint, the disaster has revealed that poor infrastructure has resulted in lead contamination in water systems across the United States—Cleveland, Ohio, Sebring Ohio, Jackson, Miss, Newark, N.J., Estes Park, Colo. and 18 Pennsylvania cities. As pointed out by presidential candidate Hillary Clinton at a recent Democratic presidential debate, lead exposure in the U.S. is also problematic in the soil, and in households containing lead paint (The Washington Post, 2016; Weesjes, 2016).

What factors influence the attention and level of government response, accountability, and effectiveness in the wake of a community harmed by a technological disaster?

Beyond lead poisoning, other types of technological failures have dominated recent U.S. headlines, such as the Las Animas Gold King Mine spill and the natural gas leak in Porter Ranch, Calif. These instances point us toward a line of critical inquiry: What factors influence the attention and level of government response, accountability, and effectiveness in the wake of a community harmed by a technological disaster? One factor worthy of scrutiny is whether the culpable party is a private operator or a government entity. For example, the water contamination in Flint, Mich., was covered up and informing the public was drastically delayed. As a result, families in Flint suffered devastatingly. Not only are government officials at all levels to blame for the inept response, it was government entities—both the state of Michigan and the town of Flint are implicated—whose decisions and actions put contaminated water into Flint households in the first place.

The same cannot be said for the Porter Ranch leak. In this case, Southern California Gas Company delayed informing the government and the community about the spill from its pipes. However, when the state was made aware of the company’s leak public officials swiftly began to address and redress the situation. The differences in government responses in Porter Ranch and Flint provoke the question: Do government reactions depend on their conceivable level of responsibility in the wake of disastrous events? That is, what role does self-preservation play in the way governments respond to disasters caused internally instead of at the hands of a private entity? Furthermore, the differences between government responses in Porter Ranch, Exide, and Flint suggest that the location of an incident and the community impacted might influence how a government responds to a hazards event.

Who suffers? Unequal risks and unequal responses to environmental hazards

Across communities government responses are not uniform. Recent articles, for example, demonstrate that the Navajo Nation has battled issues of water contamination for decades (Morales, 2016), most recently dealing with last year’s Gold King mine spill which contaminated the San Juan River—the Nation’s primary irrigation source—with arsenic, cadmium, and lead (Duara 2015). Yet very little media coverage of the spill discusses the economic impacts it has had on roughly 550 Navajo nation farmers who had to choose whether or not to continue watering their crops, either from the river or from EPA-provided barrels that were previously used for oil storage.

Furthermore, unlike the situation in Flint, no criminal investigation has been launched regarding these damages. Just west in California’s rural Central Valley, water quality has been a major concern for migrant farm workers for decades. Genoveva Isla, program director at Cultiva la Salud, points out that unlike Governor Snyder’s actions to set aside money for children impacted by lead, the state of California has not set money aside for impoverished Central Valley children who face similar long-term health issues (Sager, 2016). Meanwhile, Silicon Valley’s growing population and wealth have prompted major infrastructural investments in producing clean water for residents—something declining cities and impoverished communities aren’t able to afford (Semuels, 2016).

(L) Las Animas Gold King Mine Spill © Riverhugger (R) Southern California Gas Company's Aliso Canyon facility © Scott L.

A January Los Angeles Times editorial argues even more pointedly about divergent government responses to technological hazards (LA Times, 2016). The article compares Governor Jerry Brown’s administrative response to the Aliso Canyon gas leak in Porter Ranch to lead and arsenic contamination from the now-closed Exide battery recycling plant in Vernon. The editorial board notes that in response to the situation in affluent Porter Ranch, Governor Brown “has declared a state of emergency, ordered public health reviews, and visited residents,” while remaining absent in working class communities affected by the Exide disaster. Whereas thousands of Porter Ranch residents were relocated, no families impacted by the Exide disaster have been relocated. Further, only 191 of more than 10,000 potentially affected homes have been cleaned up, although warnings were first issued to residents nearly two years ago. I would argue that differences in community socioeconomic status and racial composition are in part why we see disparate reactions, and media coverage, in Porter Ranch, Exide, and Flint.

The question of who constitutes a responsible party also resurfaces in the comparison of Porter Ranch and Exide. The Porter Ranch gas leak represented a private sector failure. In the case of Exide’s contamination, California allowed the company to operate for 30 years on a temporary permit and with out-of-date air pollution standards, even after multiple environmental violations (LA Times, 2016). In the wake of contamination exposure, the government dismissed community claims and has continued to act with less of a sense of urgency than it did to the Porter Ranch leak.

Government accountability and the dominant collective identity of a community have the capacity to shape government responses to industrial and technological failures

While no two crises are exactly the same, the critical point is that government accountability and the dominant collective identity of a community have the capacity to shape government responses to industrial and technological failures. A community’s economic well-being and average income, predominant racial makeup, average age, geographic location, and political clout—what I would refer to as a community’s intersectional identity—can influence the level of responsibility, accountability, and standards that governments and industries are held to during such crises.

Through the lens of color and class

This is, in fact, not new. Findings in environmental justice research demonstrate the extent to which low-income communities and communities of color are burdened with uneven levels of exposure to environmental harms (Bullard 2005; Pellow 2000; Crowder and Downey 2010). Bullard (2005) demonstrates this by tracing the efforts of five African American communities working to tie social justice and environmental issues together to highlight cases of environmental injustices. Brugge et. al. (2006) compare incidents of uranium release: the 1979 United Nuclear Corporation’s Church Rock, N.M. uranium mill, the 1986 Sequoyah Fuels Corporation near Gore, Okla., and the 1979 nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island in Dauphin County, Pa. The researchers suggest that Church Rock and Sequoyah received far less attention because they occurred in rural, low-income native communities, whereas Three Mile Island was a wealthier community. Furthermore, neither Church Rock nor Sequoyah led to major policy reform for better protection (Brugge et al. 2006). These disparate patterns persist. Following a 2008 coal ash spill near the predominantly white community of Kingston, Tenn., the coal ash was transported and dumped in the predominantly black and lower-income community of Uniontown, Ala. In 2013, Uniontown residents filed a civil rights complaint with the EPA against the Alabama Department of Environmental Management for the department’s permitting actions that they contend resulted in racial disparity in public health risks (Rushing, 2016).

Such disparity appears not only in the aftermath of these tragic events. We know that disaster events often magnify vulnerabilities and inequalities that exist in communities before the onset of disaster. There are disparities in community preparedness, regulations and regulatory enforcement, and prevention and mitigation efforts. And from environmental justice research we know that some community members are more equipped with the resources, political clout, and cultural capital to resist exposure to environmental harm (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman 1995, Morrison and Dunlap 1986, Parker and McDonough 1999). Sociologist Annette Lareau’s work on concerted cultivation underscores how class and race lines influence our ability to successfully navigate the world of authority and bureaucracy, which likely play a role in a community’s ability to successfully resist proposed locations for industrial activities (McKenna, 2012). In her Uniontown testimony, Esther Calhoun makes this point clear: "Why did Uniontown become the dumping ground for the eastern half of the country, and then why did it become the dumping ground for coal ash? No one thought that the members of this poor community would fight back or that anyone would listen to us" (Calhoun, 2016).

Beyond Flint: lessons learned and directions forward

What we can take away from the host of environmental harms illustrated above is that attempts to address them are failing in a few critical ways. First, there is a lack of appropriate investment in rebuilding and retrofitting infrastructure, coupled with lax regulatory oversight and enforcement to help prevent these environmental crises. Second, where government investment in infrastructure and well-enforced industrial regulations exists, they exists selectively and unevenly. Finally, when a disaster does occur, government culpability and the predominant makeup of a community, among other things, contribute to disparate disaster response.

Social scientists need more systematic, detailed comparative case studies of technological failures to explore the relationship between community identity and government responsibility and accountability from preparedness to response and recovery. More attention should be paid to the environmental justice roots that precede technological failures, the disproportionate impacts of these failures, and the unequal responses to them by both the media and government entities. Public officials and their staff need to incorporate the well-established literature on the disparity of environmental harms and disaster vulnerability into policies that generate equitable government responses in all communities, but particularly in communities that have faced decades of environmental injustices. There are Congressional efforts to create equal funding opportunities for states with water quality issues to improve infrastructure, but the problem is that funding eligibility is contingent upon the declaration of a public drinking water state of emergency, not simply the first sign of failing infrastructure or water contamination (Semuels, 2016). It is irresponsible to delay fund for infrastructural repair until the situation digresses to a point of a state of emergency.

This proposed plan for water contamination may benefit communities that are currently suffering, but the focus on post-emergency response in the bill is still problematic. To address these environmental harms and inequalities, scholars, industrial operators, public servants, and citizens must work together to identify potential harms and injustices pre-emergency, and address them through preventative, precautionary regulations that are effectively enforced to mitigate risk, as opposed to post-disaster reactionary policies.

If Americans are committed to the notion that all lives matter, that all communities matter, the nation cannot value the health and well-being of one community at the expense of another

Finally, governments must remain committed to policies that redress these issues, seeing them all the way through. Unlike the withering commitment to reducing lead contamination, we can’t allow responsible parties—public or private—to say “good enough” and then walk away until the number of people suffering environmental harm from an incident is reduced to zero. This is particularly critical when those who suffer are disproportionately affected on the basis of age, gender, race, income, and status.

If Americans are committed to the notion that all lives matter, that all communities matter, the nation cannot value the health and well-being of one community at the expense of another. We must strive to reduce environmental harms, but the central focus must be to do so equitably.

References

Brady, Henry E., Sidney Verba, and Kay Lehman Schlozman. 1995. “Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation” American Political Science Review 89 (2): 24.

Brugge, Doug, Jamie L. delemos, and Cat Bui. "The Sequoyah Corporation fuels release and the Church Rock spill: unpublicized nuclear releases in American Indian communities" American Journal of Public Health 97.9 (2007): 1595-1600.

Bullard, Robert. 2005. “Environmental Justice in the 21st Century” The Quest for Environmental Justice: Human Rights and the Politics of Pollution, edited by Robert J. Bullard. Sierra Club Books.

Bullard, Robert. 2000. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality, 3rd Edition. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Calhoun, Esther, “An Alabama Town’s Toxic Crisis – Over Coal Ash” Savannah Now, February 14, 2016. http://savannahnow.com/column/2016-02-14/esther-calhoun-alabama-towns-toxic-crisis-over-coal-ash# (accessed April 15, 2016).

Crowder, Kyle and Liam Downey. 2010. “Inter-Neighborhood Migration, Race, and Environmental Hazards: Modeling Micro-Level Processes of Environmental Inequality” American Journal of Sociology 115(4): 1110-1149.

Duara, Nigel, “How the Gold King Mine spill continues to affect Navajo life” Los Angeles Times, November 25, 2015. http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-ff-navajo-qa-20151125-story.html (accessed on April 15, 2016).

Fournier, Ron., “Snyder Concedes Flint His “Katrina,” a Failure of Leadership” The Atlantic, January 18, 2016 http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/01/snyder-concedes-flint-is-his-katrina-a-failure-of-leadership/463068/ (accessed on April 15, 2016).

LA Times. 2016. “Why does affluent Porter Ranch get more urgent environmental relief than working-class Boyle Heights?” Los Angeles Times, January 29, 2016. http://www.latimes.com/opinion/editorials/la-ed-exide-20160131-story.html (accessed on April 15, 2016).

McKenna, Laura. 2012. “Explaining Annette Lareau, or, Why Parenting Style Ensures Inequality” The Atlantic, February 16, 2012. http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2012/02/explaining-annette-lareau-or-why-parenting-style-ensures-inequality/253156/ (accessed on April 15, 2016).

Morales, Laurel. 2016. “For the Navajo Nation, Uranium Mining’s Deadly Legacy Lingers” NPR, April 10, 2016 http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/04/10/473547227/for-the-navajo-nation-uranium-minings-deadly-legacy-lingers (accessed on April 15, 2016).

Morrison, Denton E., and Riley Dunlap. 1986. “Environmentalism and Elitism: A Conceptual and Empirical Analysis” Environmental Management 10 (5): 581-89

Parker, Julia Dawn, and Maureen H. McDonough. 1999. “Environmentalism of African Americans: An Analysis of the Subculture and Barriers Theories” Environment and Behavior 31 (2): 155-77.

Pellow, David N. 2000. “Environmental Inequality Formation: Toward a Theory of Environmental Injustice” American Behavioral Scientist 43(4): 581-601.

The Washington Post. 2016. “Transcript: The Democrats’ debate in Flint, annotated” The Washington Post, March 6, 2016 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/03/06/the-democrats-debate-in-flint-mich-annotated/ (accessed on April 15, 2016)

Young Molly, 2016. “Ex-FEMA head says Flint water crisis should have used lessons from Katrina” MLive, January 20, 2016 http://www.mlive.com/news/flint/index.ssf/2016/01/government_didnt_learn_from_hu.html (accessed on April 15, 2016).

Rushing, Keith., 2016 “Coal Ash Dump in Alabama’s Black Belt — Another Symbol of Racism’s Staying Power” Huffington Post, February 12, 2016 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/keith-rushing/coal-ash-dump-in-alabamas_b_9220854.html (accessed on April 15, 2016).

Semuels, Alana, 2016. “A Tale of Two Water Systems” The Atlantic, February 29, 2016 http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/02/a-tale-of-two-water-systems/471207/ (accessed on April 15, 2016).

Sager, Rebekah, 2016. “Like Flint, water in California’s Center Valley unsafe, causing health problems” Fox News Latino, March 8, 2016 http://latino.foxnews.com/latino/health/2016/03/08/like-flint-water-in-california-central-valley-unsafe-causing-health-problems/ (accessed on April 15, 2016).

Weesjes, Elke, 2016. “Weakened Resolve – Flint Crisis Hasn’t Steeled the Nation Against the Health Risks of Lead” Disaster Research, March 11, 2016 https://hazards.colorado.edu/article/weakened-resolve-flint-crisis-hasn-t-steeled-the-nation-against-the-health-risks-of-lead (accessed on April 15, 2016).

Stacia Ryder is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at Utah State University. She received her PhD in sociology in 2019 from Colorado State University and worked as a postdoctoral research in the Department of Geography at the University of Exeter from 2019-2023. Stacia uses a critical approach to examine how power dynamics create justice issues in environmental, energy and climate contexts. She has authored several publications on such subjects. Stacia aims to create concrete social change by working with communities to center just and equitable transitions as essential components of climate planning and policy.