Q & A with Kristina Peterson

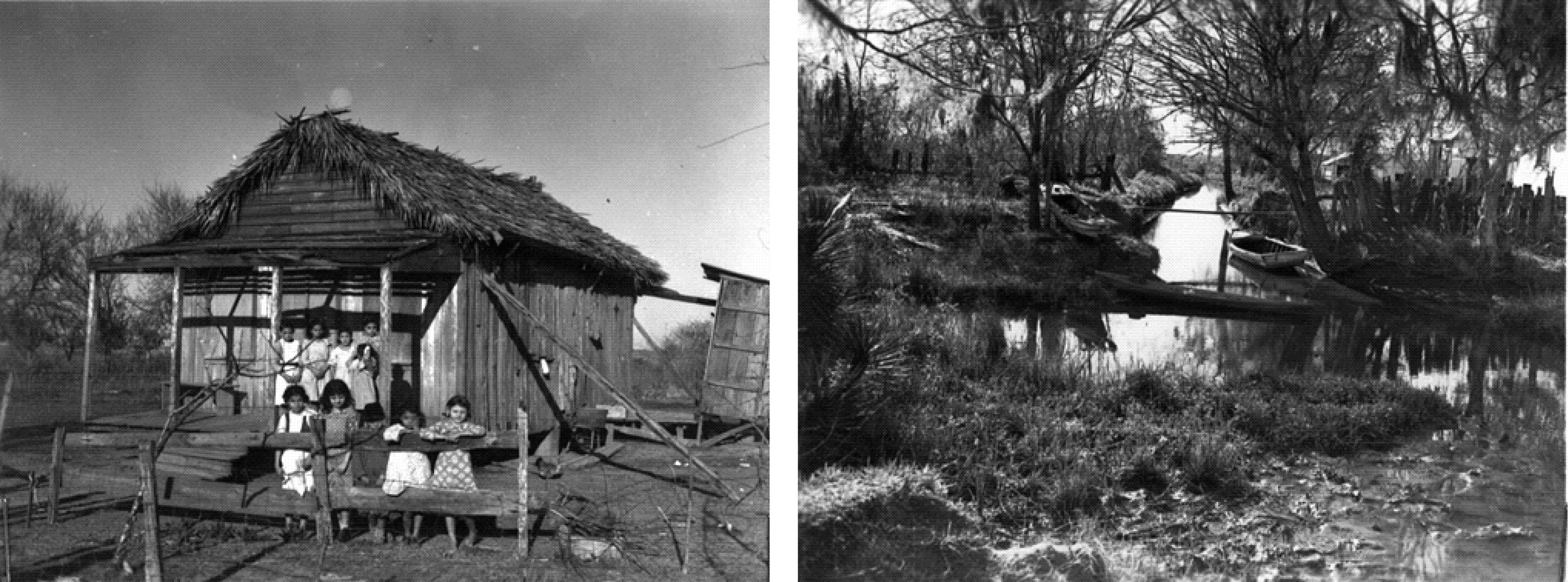

(L) Isle de Jean Charles. Island home with thatched roof (R) One of the many bayous that cleaves Isle de Jean Charles © New Deal Network 1938

KRISTINA PETERSON, former senior research associate with the Center for Hazards Assessment Response and Technology at the University of New Orleans (UNO-CHART), is the director facilitator of the Lowlander Center, a nonprofit that supports people living in Louisiana’s lowland region through education, research, and advocacy.

The Lowland Center has been closely involved with the resettlement of the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe. The tribe has been at the front lines of Louisiana’s coastal land loss—the land it has inhabited for generations is vanishing before their eyes. In the past century, Isle de Jean Charles has been shrinking and today only about two percent of the tribe’s ancestral home is left. The tribe recently received a $48 million award from the National Disaster Reduction Competition (NDRC) sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Rockefeller Foundation.

“This award will allow our tribe to design and develop a new, culturally appropriate and resilient site for our community, safely located further inland,” the Chief Albert Naquin was quoted as saying on the Lowlander Center website.

Together with a team of nationally recognized indigenous and non-indigenous professionals, the people of the Lowlander Center are assisting with the tribe’s relocation process farther inland, which they hope will become “a living model of community cultural resilience, disaster and climate change mitigation, green building practices, environmental stewardship, and sustainable economic development (Lowlander Center, 2016).

I recently spoke to Peterson by email about the center and its involvement in the tribe’s pioneering relocation efforts.

(L) Isle de Jean Charles after Hurricane Gustave 2008 © Karen Apricot

Q: The Lowlander Center is a nonprofit that was founded in 2012. How did the center come about?

A: The coast of Louisiana and its amazing people are challenged by the fastest disappearing delta in the world. This challenge is complex in that it impacts historied communities of place that have been stewards of the estuaries—their “life world.” The Lowlander Center was formed to team up with the various coastal communities, indigenous and non-indigenous, to support their efforts to continue to thrive in the face of the many challenges. Some communities are focusing their efforts on remaining in place, while others such as Isle de Jean Charles, have come to the difficult decision that moving further inland is their only option. The Lowlander Center and its board members have a long history of partnership with Isle de Jean Charles and have supported Chief Albert Naquin’s efforts to identify resources and partners for their resettlement effort.

Q: The team of Isle de Jean Charles and the Lowlander Center have created a new website about the resettlement of the Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indians. What do you hope to achieve with this website?

A: We would like to tell the story of the incredible work and history of the Isle de Jean Charles Tribe and their courageous work to step out in uncharted territory—climate resettlement. To do justice for a “to a seventh generation community”1 that serves the people of the tribe and the eco-system that supports them, a very holistic and integrated approach has to be taken. We are hoping that the site will help provide a platform for people to learn in real time what going on with the tribe’s work and to link this work with others who are being challenged, nationally and internationally, with resettlement.

Q: Isle de Jean Charles has lost the majority of its land and population to coastal erosion and rising sea levels in the past 100 years. In January, the tribe received $48 million for resettlement. How difficult was it to obtain this funding and what can other tribal communities—for example, those in Alaska—learn from the Isle de Jean Charles tribe?

A: The funds involve resettlement but are fundamentally geared towards developing an exemplary sustainable, resilient coastal community that will stand the test of time. This was the goal of HUD’s National Disaster Resiliency Competition that awarded the funds. The resettlement becomes a proof of concept in using best technologies, best practices, and the best knowledge of process for human dimensions in cultural retention and lifeway2 transfer. The community will be a teaching center for other communities that want to apply mitigation measures and to understand the complexities of resettling in context with changing eco-systems—and in some cases rapid social and lifeway threats. The team that led the application efforts partnered with the tribal council and the community to , engaged in an in-depth planning effort, compressed into a brief timeline in a short amount of time. Community engagement in the process is also an element of the best practices that are being implemented. There were many challenges associated with completing the application, particularly in a way that made it both competitive and culturally appropriate. When it comes to proposal development, small communities and non-profits are at a disadvantage compared to large consulting firms. However, we had the benefit of a wonderful team of local and national supporters who were willing to share their extensive expertise in support of the tribe. And the tribe contributed their commitment to participating in numerous meetings, often having to take time from their employment to do so.

(L) Isle de Jean Charles. Pirogue on the Bayou (R) Victor Naquin, Chief of Isle de Jean Charles, standing in the rear of a WPA classroom. In front are seated a number of the Islanders ready for a lesson in writing. © New Deal Network 1938

Q: What are the biggest challenges that lie ahead for the Isle de Jean Charles Tribe?

A: Although the grant has been awarded, the tribe has not yet received the grant nor do they know under what conditions they will be receiving the monies. The grant will be given to the State [of Louisiana] directly and the state’s negotiations with HUD regarding the details have not been transparent. The team that worked on the proposal for two years is a mixture of experts from both the tribe and from relevant disciplines. The trust that has been built during that time period is reflected in the quality of design that, in turn, reflects the cultural, economic, and continued growth of the tribe. The benefits are a projected, long-lived community that can re-gather a people who have been scattered by former storms and disasters. The re-gathering serves to strengthen traditional mutual aid, community self-sufficiency, and agency. At the same time, the process of leaving the island is a difficult and complicated emotional journey for community members who have slowly watched their land erode from under them for so long.

Q: $48 million for the resettlement of 400 tribe members doesn’t seem quite enough. Or is it?

A: The community will be learning through the evaluation process. They are the best folks to help interpret the work for others. Between the proof-of-concept design, the complex evaluation process for transferability and the need for a minimum of 100 homes, $48 million is not enough. Additionally, resettlement entails far more than building houses, as biodiversity must be returned to the new land, infrastructure installed, and economic livelihoods insured. It is important to remember that what is being created is a prototype that will explore various applied mitigation strategies that could be beneficial for a resilient coast. When developing prototypes or proof-of-concept pieces, some applications may be more expensive up front, but allow for the testing of new green, resilient building materials and building designs that could offer savings not only to the immediate location, but also can result in future savings that can be transferred to other communities and building standards. There is a need for a layered approach to evaluation methods that allow the team to understand the intersection of physical, social, and political forces so that appropriate measures can be formed to mediate obstacles.

(L) Isle de Jean Charles after Hurricane Gustave 2008 © Karen Apricot

Q: Twice before, in 2002 and 2009, the tribe voted in favor of relocation, yet it wasn’t realized. What happened?

The tribe has discussed the need for resettlement for 16 years. The first time this was discussed, the [U.S. Army] Corps of Engineers wanted the tribe to have 100 percent buy-inparticipation in order to give them the funds to resettle. The tribe had 85 percent buy-in at the time and could not meet those qualifications. The second attempt was met with not-in-my-backyard resistance by the neighbors in the proposed location. The surrounding community was able to prevent the sale of the property. This is the third attempt of the tribal council to resettle the community. It is imperative in that their homeland is quickly disappearing and the close family/community support systems are being strained by the dislocation of individual families.

Q: How will the Isle de Jean Charles tribe protect itself from future disasters in its new location in Terrebonne Parish, South Louisiana?

A: The first facility the community would like to build when they are able to acquire land is a community facility that can serve as a hurricane and tornado shelter. The [Federal Emergency Management Agency]-rated shelter will serve the Tribe in the next storm, as well as a neighboring tribe, the Pointe au Chien, thus keeping family and community together in a safe spot. The tribe, using a permeable playfield surface design that can double for campers, will be able to house families that would potentially be displaced during the next storms and keep them in the context of the community until their homes are built in the new location. There is a potential disconnect between now and when homes can be built and the possibility of a devastating storm.

The over-all design of the community brings together all the best practices in water usage, mitigation measures, energy and self-sustainability. The tribe, once an extremely self-sufficient people, will be able to regain a new level of self-sufficiency with indigenuity (indigenous ingenuity) that can serve as a new coastal standard.

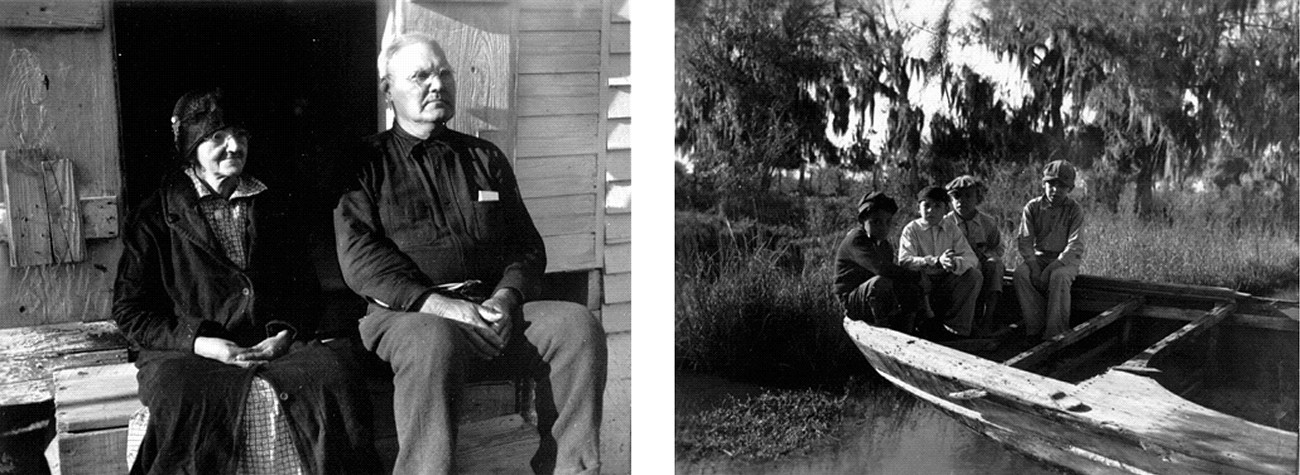

(L) Island Chief Victor Naquin and Wife (parents of Chief Albert Naquin (R) Island Children © New Deal Network 1938

Q: What is next for the Lowlander Center and for you personally?

A: We would like to see this come to fruition, learn from what we did with the tribe, and enjoy the outcome with our friends. We also want to continue the work with other communities that are imagining their resilience or adaptation a bit differently than Isle de Jean Charles and learn from their efforts. For me personally, I want to continue to explore the need for designated, set-aside lands held for future community relocations. Just as national forests are used for economic and resource protection by protecting natural areas, we may need to explore policies that will develop “green lands.” These lands could be used for environmental or green services that counter negative climate impacts, while keeping them open for future community development.

-

Seventh Generation is a indigenous concept that understands that all of creation has to be stewards of the resources for seven generations in the future or in perpetuity. ↩

-

Lifeway is a word that Kyle Whyte is using in lieu of culture in that many people understand culture as very limited whereas lifeway encompasses all of what we do as a people. ↩

Elke Weesjes Sabella is former editor of the Natural Hazards Observer. She joined the staff in December 2014 after a brief stint as a correspondent for a United Nations nonprofit. Under her leadership, the Observer was revamped to a more visual format and one that included national and international perspectives on threats facing the world. Weesjes was the editor of the peer-reviewed bimonthly publication United Academics Journal of Social Sciences from 2010 to 2013.

Weesjes Sabella also worked as a research associate for the Center for Disaster and Risk Analysis, formerly located at Colorado State University (although no longer active). In that role, she collected and analyzed data and translated research findings for a broader audience. She played a central role in finalizing the Disaster Preparedness among Childcare Providers in Colorado project, which examines all-hazards preparedness in daycares and in-home childcare across Colorado. She co-authored the report based on the first stage of the project, which was funded by Region VIII of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Weesjes Sabella specializes in cultural memory and neighborhood/community change in times of acute and chronic stress. She has published articles on the impact of drought on farming communities in Kansas, the effects of Superstorm Sandy in Far Rockaway, Queens, urban renewal in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, and health services for vulnerable populations in the South Bronx.

Weesjes Sabella received her PhD from the University of Sussex. Her dissertation, Children of the Red Flag: Growing up in a Communist Family During the Cold War (2012), as well as the majority of her publication record, share the common methodology of understanding culture and identity through oral history.