2011, 73 min.

2011, 73 min.

Director: Steven Suderman

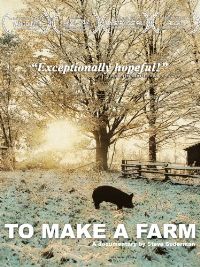

IN THIS 2011 documentary, Director Steven Sunderman follows five young, first-time farmers in Ontario and Manitoba, Canada. The beautifully shot To Make a Farm documents their experiences as they embark on making agriculture dreams reality. Starting from scratch, they meet the risks and challenges of this demanding profession with passion and sacrifice.

This new crop of farmers—who belong to a generation that grew up in the digital age, but favors old-school things such as farmer’s markets, microbreweries, and artisan foods—have a common traits: a concern for social justice and the environment, coupled with doubt that mainstream political structures can address these issues.

At first sight, these farmers resemble the back-to-the-landers of the 1970s. Back then, millions of people in North America alone—mostly young, educated, white, and middle-class—tried homesteading on farms and in communes. These back-to-the-landers were repulsed by the value system of western society, the rat race, consumerism, and the destruction of the environment. They wanted to invent a new and better civilization in the country—self sufficient, close to nature, and far from pollution. Many, if not most, were unrealistic about what it would take to make the transition from the city to the country life. They learned the hard way that the life of a farmer is physically and financially difficult and that it is almost impossible to become independent from the mainstream economy. They underestimated the amount of money and technological knowledge necessary to set up shop in rural areas. By the 1980s, the back-to-the-land movement had disintegrated, communes and marriages had buckled under financial pressure and other hardships, and many back-to-the-landers returned to their previous lives.

The North American agrarian community has been graying ever since. The average age of a farmer in Canada and the United States is 54 and 58 years old, respectively. Feeling dissatisfied with rural livelihoods, young adults have been moving to more populated areas for decades. But in some places in North America, that trend is reversing. Small-scale sustainable agriculture is on the rise and there is a new crop of young idealistic farmers to thank for it. Sunderman shows that, unlike the majority of their 1970s predecessors, his protagonists could have what it takes to survive on the farm—or at least survive a little longer.

Small-scale sustainable agriculture is on the rise and there is a new crop of young idealistic farmers to thank for it

Sunderman’s subjects are two couples and a single man who don’t have generations of agricultural knowledge to tap into. They have to learn by doing. Making money is definitely a concern for these farmers and to do so, they use the strategy of cutting out the middleman and selling directly to the customers.

We first meet Leslie Moskovitz and Jeff Boesch, owners of the 100-acre Cedar Down Farm in Hanover, who have a challenging business model. Their customers pre-order and pay for their produce even before the couple start planting in the beginning of the agricultural year. This puts them under a lot of pressure, not only to deliver fresh and delicious fruits and vegetables, but also in the right quantity. The pressure only increases when they find out that their soil is deficient in potassium.

Tarrah Young and Nathan Carey of Green Being Farm—a 50-acre organic operation in Neustadt—have a less precarious business model. They raise farm animals such as pigs, sheep, turkeys, and chickens and grow organic vegetables, which they sell to their online customers and directly to people in their neighborhood. Young, the driving force behind the operation, has a personal connection to the land and her animals. She treats her pigs and sheep like pets and confesses that she finds it hard to send them to the slaughterhouse.

In her last semester at college, Young took an introduction to organic agriculture class and was instantly sold. She explains that what attracted her most is the fact that farmers can make a real difference on environmental issues, something that isn’t always possible for people in other professions. She enjoys being an active participant in treating the planet well while bringing people nutritious and sustainable food.

Wes Huyghe, the last farmer in the film, experiences firsthand that growing food isn’t as easy as some might imagine. He just bought two acres of land and tries to figure out how to grow vegetables with almost no equipment at all. He lives all by himself in a tent next to his land. Even the most basic tasks, like irrigating his crops, are a huge challenge. When his savings are depleted, Wes is forced to find a second job to generate some income. Just before his dream of living off the land is about to die, he finds a water well nearby that he can substitute more expensive water sources. With his irrigation problems solved, he successfully grows his first crops. His produce is a big hit with the locals who, curious to see what this bearded, long-haired man is all about, flock to his farm stand.

To Make a Farm, which was released in the United States late 2015, carefully balances these small victories with the many struggles and hardships young farmers face. Suderman makes it clear that life on the land is not for the fainthearted—money is tight, the hours are long, there’s barely time to socialize, and the work is labor-intensive. Additionally these farmers struggle with devastating weather events, such as hail, severe rainfall, drought, and snow.

Spending time with these young farmers encouraged Suderman, who himself grew up on a farm in western Canada, to reflect on his own childhood. He admits that, when he was growing up, it never occurred to him that his parents were producing food. They did not have the option to care much beyond making a profit and were forced to mass-produce standardized products that “barely nourished our bodies, never mind our souls.” His parents’ story didn’t end well. After five generations, they were forced off the family farm by corporate competitors.

According to their respective websites, Suderman’s farmers are all still going strong. There are a number of reasons why they have fared better—so far—than their hippy forebears. Unlike back-to-the-landers that eschewed technology, today’s young small farmers are tech savvy and business wise. They have websites and social media accounts, which helps them increase their customer base and stay in touch with people from their past lives. This is a stark contrast to the experiences of the back-to-the-landers, who relied on word-of-mouth business and were completely cut off from mainstream society.

Today, organic farming is big business and organic food is everywhere from supermarkets to corner stores

Another important difference between young first-time famers then and now is the today’s organic-friendly consumers. Today, organic farming is big business and organic food is everywhere from supermarkets to corner stores. Back then, hippy farmers only had a counterculture movement to market to.

While it is true that small-scale sustainable farming has changed significantly and is more likely to be a successful venture—even for first-time farmers—than it was 40 years ago, the farmer’s Suderman followed are still among the fortunate few. Most small farmers, organic or otherwise, struggle financially. Many are unable to survive without off-farm income. In fact, according to 2012 U.S. Department of Agriculture data, intermediate-size farms (farms that gross more than $10,000 but less than $250,000) obtain about 10 percent of their household income from the farm and 90 percent from an off-farm source. The situation in Canada is similar.

Small organic farms like those featured in the film are almost always not financially sustainable. They may be certified organic, the owners might manage soil fertility through crop rotation and avoid synthetic pesticides, and they conserve water. But these farms rely on uncompensated labor and self-exploitation. Until these farmers can get things like government funding and healthcare, their businesses can’t be called sustainable and their future is uncertain.

Further reading:

Eleanor Agnew. 2005. Back from the Land: How Young Americans Went to Nature in the 1970s, and Why They Came Back. Ivan R. Dee Publisher, Chicago.

Elke Weesjes Sabella is former editor of the Natural Hazards Observer. She joined the staff in December 2014 after a brief stint as a correspondent for a United Nations nonprofit. Under her leadership, the Observer was revamped to a more visual format and one that included national and international perspectives on threats facing the world. Weesjes was the editor of the peer-reviewed bimonthly publication United Academics Journal of Social Sciences from 2010 to 2013.

Weesjes Sabella also worked as a research associate for the Center for Disaster and Risk Analysis, formerly located at Colorado State University (although no longer active). In that role, she collected and analyzed data and translated research findings for a broader audience. She played a central role in finalizing the Disaster Preparedness among Childcare Providers in Colorado project, which examines all-hazards preparedness in daycares and in-home childcare across Colorado. She co-authored the report based on the first stage of the project, which was funded by Region VIII of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Weesjes Sabella specializes in cultural memory and neighborhood/community change in times of acute and chronic stress. She has published articles on the impact of drought on farming communities in Kansas, the effects of Superstorm Sandy in Far Rockaway, Queens, urban renewal in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, and health services for vulnerable populations in the South Bronx.

Weesjes Sabella received her PhD from the University of Sussex. Her dissertation, Children of the Red Flag: Growing up in a Communist Family During the Cold War (2012), as well as the majority of her publication record, share the common methodology of understanding culture and identity through oral history.