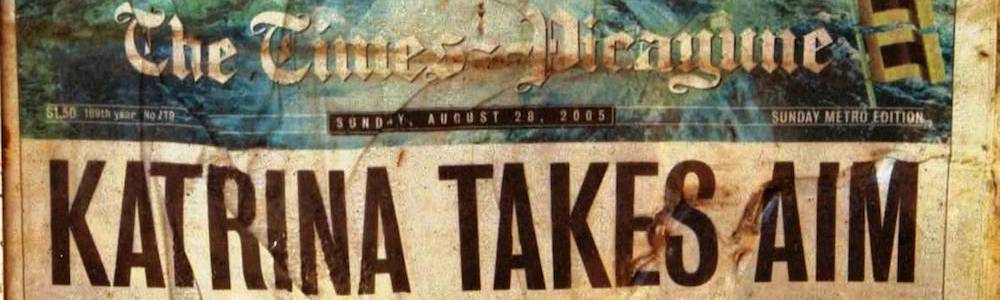

A pre-hurricane headline survived in a vending machine that floated to higher ground. ©Steve Kroll-Smith, 2005.

A pre-hurricane headline survived in a vending machine that floated to higher ground. ©Steve Kroll-Smith, 2005.

By Steve Kroll-Smith, Pamela Jenkins, and Vern Baxter

Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Jose, and Maria smashed records for rainfall, wind speed, storm diameter, and more. Given all the devastation wrought, we will surely continue to hear a good deal in the weeks and months to come about recovery. This is how it typically goes, as the word disaster almost always conjures up the word recovery. Its past tense—recovered—is, after all, disaster’s coda. The prefix re- signals a going back, as in return or revert. To become, in short, as we were before.

The word itself, has about it the scent of a final vocabulary. In 1848, John Stuart Mill wrote a joyful ode to recovery:

...what has so often excited wonder, the great rapidity with which countries recover from a state of devastation; the disappearance, in a short time, of all traces of the mischiefs done by earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, and the ravages of war… a few years after, everything is much as it was before.

Mill focuses on infrastructure recovery, as does the recent New York Times piece on Harvey. But restoring a power grid or rebuilding a house is not the same as refashioning a sense of self; a more or less coherent idea about who and what I am as a survivor of catastrophe.

In Pontchartrain Park, a flood-stained communion dress is salvaged from the wreckage of Hurricane Katrina. ©Pamela Jenkins, 2005.

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey, New York Times Reporter Benedict Carey visited New Orleans to interview a few people, now in their 20s, who lived through Hurricane Katrina. Each person he spoke to conveyed a struggle to find something or someone to hang on to as the years went by; an anchor, a shelter from a storm inside them that will not abate. Each returned to New Orleans, not to home as they knew it, but, in Carey’s telling, “to a permutation of it, one with an existential uncertainty that is no abstraction.”

We too found this “existential uncertainty” in our interviews with Katrina survivors. Four years after the storm, we spoke to Jesse Gray, a life-long resident of New Orleans. He and his wife Denise were once again living in Hollygrove, a modest neighborhood in the heart of the city. Their house rehabbed, we sat looking out on their trimmed yard and asked Jesse how he was doing. Gazing up, as if talking to the ceiling, he told us: “About a year ago I started having nightmares. I couldn’t get rid of my nightmares. I’d wake up at night soaking wet… I’ve been trying to wake up right, but you can’t wake up right.”

A year later, we spoke with Jesse again. It had now been close to five years since Katrina swamped the city. Jesse’s nightmares had continued, but now they were filled with shadows of a tragedy no parent should endure. In May of 2010, Jesse’s son was murdered; the victim of a neighborhood robbery.

“Since Katrina and then my son got killed, I’ve been taking time to see a psychiatrist once a month,” he recounted. “I go to a PTSD group twice a month. I sing in the choir on weekends.” We watched and listened over the years as Jesse weathered the mayhem of an historic flood only to face a parent’s true nightmare. How much of the variance in Jesse’s experience is explained by the word recovery?

Jolinda, another participant in our study, lived in Pontchartrain Park when the city flooded. She evacuated. She returned and restored her flooded house. Five years later, in 2010, she found herself sitting in church connecting to what she said matters most in her life, her relationship with God. But Jolinda could not help noticing “a pain on my left side. And I felt dizzy. I began to perspire.” She left church and called 911. “An ambulance picked me up.” Jolinda paused at this point in the interview, took a breath, and noted methodically, “Miss Katrina is not finished with me.”

In her turn of phrase, Jolinda reminds us of the overreach of this ubiquitous word recovery. Years after a catastrophe enters the history books, it continues, in its morphing ways—perchance blending with other losses—to bend and shape lives.

Jesse, Jolinda, and the many other people we spoke with years after the city flooded forced us to acknowledge the often unbridgeable gap between their misery and our analytic vernacular. As we think about how best to deploy our research skills and collective wisdom to make some viable sense of the miseries in the wake of these storms of 2017, perhaps some of us will look for words that reach beyond the finality of recovery to offer something that better captures the complex ways disasters continue to reverberate through people’s lives. For the many people who talked with us years after the flood, Katrina is not something they lived through, but rather, something they live with. A lesson worth remembering.