Planning for Post-Disaster Needs of Women With Breast Cancer in Puerto Rico

Publication Date: 2022

Executive Summary

Overview

Women diagnosed with chronic illnesses are uniquely vulnerable to injury and death during a disaster. Among women 45 to 84 years old in Puerto Rico, breast cancer is the leading cause of death. It is estimated that 30% of the new cancer cases diagnosed in women in the island are breast cancer. Since 1987, the incidence rate of invasive breast cancer increased 1.5% per year, while in-situ breast cancer has increased 7.4% per year. The Southwestern part of the island had the highest rate of late-stage breast cancer in the island. Additionally, Southwest Puerto Rico is the poorest area in the island. For example, the municipality of Guánica had more than 60% of their population living under the poverty line and population decrease of 29% from 2010 to 2020. This had left the area with a fragile health care infrastructure and unable to meet the healthcare needs of its residents. The 2017 Hurricane Maria, the 2020 earthquakes, and the current COVID-19 pandemic led to the collapse of the healthcare system in Southwestern Puerto Rico. The collapse of the health care system due to the consecutive disasters interrupted cancer care for hundreds of women. The interruption of cancer care, unstable housing options, and unreliable transportation systems due to concurrent and consecutive disasters created immense stress on women. Addressing the psychosocial needs of breast cancer patients leads to a better quality of life. There is a need to understand the specific psychosocial needs of breast cancer patients in this region.

Research Questions and Design

This research examined the psychosocial needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer that received services by nonprofit organizations during concurrent and consecutive disasters in Southwest Puerto Rico. We asked the following research questions:

- What are the psychosocial needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer after concurrent and consecutive disasters in Southwest Puerto Rico?

- What strategies do organizations use to meet the psychosocial needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer after concurrent and consecutive disasters in Southwest Puerto Rico?

- How can community partners improve service delivery and promote resiliency?

Data collection is being done through a combination of in person and telephone surveys, interviews, and focus groups with women diagnosed with breast cancer that received services by nonprofit organizations during concurrent and consecutive disasters in Southwest Puerto Rico. Researchers from the University of Utah are collaborating closely with two leading nonprofit organizations in Southwest Puerto Rico: Connecting Paths and Esfuerzate y Se Valiente to conduct this study. A unique aspect of this study is that it includes women diagnosed with cancer who received services by nonprofit organizations during consecutive disasters as researchers.

Preliminary Findings

The research team has completed 23 surveys and 10 interviews. Study findings show that women diagnosed with breast cancer during concurrent and consecutive disasters in Southwest Puerto Rico have unique needs. These women experienced economic hardships due to their diagnosis and their experiences with disasters. They experienced damages to their homes, housing instability because of the disasters, limited access to transportation, and the interruption of their cancer treatment. This created significant phycological distress that resulted in high levels of depression and anxiety. Nonprofit organizations stepped in and provided cancer support groups, access to transportation, housing arrangements, and access to health and psychological care to women diagnosed with breast cancer during disasters. These interventions addressed issues of inequitable recovery and increased resiliency.

Public Health Implications

This study can improve the public health response after concurrent and consecutive disasters by shedding light on the psychosocial needs of breast cancer patients in Southwest Puerto Rico. As Hurricane Maria, the 2020 earthquakes, and the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the treatment for hundreds of breast cancer patients in the region, our survey, interviews, and focus groups captured topics of great importance such as barriers to transportation, unstable housing, and the need for psychological services. As nonprofit organizations are a vital component in disaster recovery in Puerto Rico, the information gathered will impact nonprofit organizations in three ways. First, understanding this will allow the organization to better understand the strategies that address the psychosocial needs of its participants. Second, it will shed light on how partnering and collaborating with other organizations or agencies improves service delivery and increases resiliency among breast cancer patients. And third, by understanding this there is an opportunity to engage the healthcare community in the island to better understand their disaster preparedness plans. The engagement of the healthcare community can create a framework for developing emergency preparedness plans to address access issues for women and others in the breast cancer community. This information is relevant to nonprofits and public or private healthcare agencies, public or private that aim to improve their services, build organizational capacity, and increase resource sharing.

Introduction

In Puerto Rico, cancer is the leading cause of death among adults (Rodriguez-Rabassa et al., 20201), and its detection rate is increasing at a rate of 1.5% per year (Castro et al., 20172). The most common types of cancer are breast cancer for women and prostate cancer for men (Torres-Cintrón et al., 20103). Hurricane Maria, the 2020 earthquakes, and COVID-19 led to the collapse of the healthcare system in the southern region of Puerto Rico, interrupting cancer care for thousands of patients (Sanabria-Leon et al., 20214). Interruptions in treatments due to disasters can dramatically impact the patients’ physical and psychological outcomes (Sahar et al., 20205). Disasters can interrupt cancer care delivery through loss of transportation, damage to infrastructure, and the loss of functionality of medical services needed for early detection and treatment (Gorji et al., 20186). Continuous care is essential for breast cancer patients, because evidence shows that delays of three months or more lowers the chance of survival five years later by 12% (Richards et al., 19997). Similar studies show that cancer survivors who had been exposed to disasters, such as hurricanes and earthquakes, had decreased chances for long-term survival (Man et al., 20188).

Using surveys, interviews, and focus groups this study examines the psychosocial needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer, the services they received from nonprofit organizations during concurrent and consecutive disasters in Southwestern Puerto Rico, the specific strategies nonprofits use to meet their needs, and how community partners could improve the delivery of these services. In collaboration with two nonprofits organizations, Connecting Paths and Esfuerzate y Se Valiente, the researchers (which included women who either worked with or received services from partner organizations) interviewed women from Southwestern Puerto Rico who were diagnosed with breast cancer during the last 5 years.

Literature Review

Patients that are diagnosed with chronic illnesses such as cancer often experience a worsening of the disease during disasters due to four reasons: First, disasters often break the continuity of cancer treatment for many patients. Second, people diagnosed with care experience an increase in disaster related stress due to disasters. Third, disasters often partially or completely disrupt emotional and psychological support systems such as family and community. And fourth, cancer patients are often not prioritized during disaster response efforts (Sahar et al., 2020). Some studies have suggested that the interruption on cancer care is devastating for cancer patients where a delay as short as two weeks can negatively impact the survival rate of certain patients (Sahar et al., 2020). The interruption of care by disaster has devastating psychological consequences for a population already susceptible to psychological adversities due to their diagnosis. Research studies suggest that psychological disorders, such as anxiety and depression tend to affect up to 20% of people with a cancer history, compared with 5% for the general population (Sahar et al., 2020). Breast cancer patients reported having one of the highest rates of depression and anxiety among cancer patients (Nikbakhsh et al., 20149). Disasters can aggravate these conditions, severely impacting the psychological state, and overall health, of breast cancer patients.

In Puerto Rico, during Hurricane Maria, the 2020 earthquakes, and the COVID-19 pandemic cancer survivors reported significantly high levels of psychological distress caused by lack of employment, a secure home, electricity services, reliable transportation, food, or access to health care (Rodriguez-Rabassa et al., 2020). Consecutive disasters such as the 2020 earthquakes and the COVID-19 pandemic aggravated the already limited access to essential oncological health care and services in Southwest Puerto Rico. Stress and cancer-related burden provoked by disasters seem to be gendered, as women report having two times higher stress than men (Castro et al., 2017). There has been significant debate in the literature as to whether the psychosocial needs of women in Puerto Rico are being addressed. Primarily, there is a need to understand better the specific psychosocial needs of breast cancer survivors in Puerto Rico (Castro et al., 2015b10).

According to Castro et al. (2017) one of the best ways to address psychological distress in breast cancer patients is to provide social support. This social support can involve such things as providing access to support groups, transportations resources, and education and information regarding cancer treatment. This is supported by other research that suggests that addressing the psychosocial needs of breast cancer patients through social support groups is crucial in overcoming several common barriers to treatment, leading to better adjustment to the cancer diagnosis (Salakari et al., 201711). Furthermore, it is paramount to identify factors that promote and influence resilience and well-being among women diagnosed with breast cancer during disasters (Rodriguez-Rabassa, 2020).

Previous research has identified that health care providers in southwestern Puerto Rico were greatly concerned about the psychosocial needs of cancer patients following the concurrent and consecutive disasters (Torres-Cintrón et al., 2010). These health care providers identified needs such as transportation, financial support, social support, education regarding cancer treatment and prevention, and the need to access professional psychosocial services (Castro et al., 2017). However, a study conducted by Castro et al., (2017) revealed a potential gap in integrating clinical cancer care services and supportive services for cancer patients and survivors in Puerto Rico. Castro et al., (2017) found that 84% of participants needed support groups, health education, and psychological treatment but doctors and health care providers were unable to connect patients to these services. The authors argue that the second most requested non-clinical services cancer patients requested in Puerto Rico was psychological services and social support aim to alleviate the mental health burden produced by a cancer diagnosis. There is a lack of integration between patients, nonprofit organizations, and the health care system in the island to provide coordinated physical and psychological cancer care (Castro et al., 2015a). Therefore, there is a need for comprehensive research studies that examine the availability and accessibility of mental health services that address psychosocial needs in the southwestern part of the island during concurrent and consecutive disasters (Castro et al., 2017). Addressing psychosocial factors, such as the development of support group-based interventions, along with clinical cancer care, has been shown to decrease anxiety and depression (Shen et al., 202012), increase resiliency, and improve their overall quality of life (Ristevska-Dimitrovska et al., 201513).

A previous mixed methods study conducted by authors of this report with healthcare and community nonprofits in Puerto Rico found that these organizations adapt in response to concurrent and consecutive disasters (García et al., 202114). This research also found that nonprofit organizations adapted by changing missions, programs, and target populations. They also became more efficient at facilitating information flows, filling resource gaps, and mediating between the government and residents in recovery planning efforts (García et al., 2021).

We know from previous literature that networking can help nonprofits with new avenues of information and action and improve their capacities (Quarantelli, 198815; Smallman & Weir, 199916). However, few studies have systematically analyzed the benefits of inter-organizational communication and capacity building between community organizations to serve a specific target population despite these insights. In addition, while nonprofit organizations play critical roles in response to disasters and public health concerns, there is not substantial research about the impacts of concurrent and consecutive disasters on populations that already had chronic diseases and how nonprofits serve them.

Research Design

Study Site Description

Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, the largest breast cancer foundation in Puerto Rico, identified the Southwest region of Puerto Rico as a high priority for health interventions (Komen, 201517). This area has the highest rate of late-stage breast cancer detection in the island and receiving care and supportive services in the region is difficult because it lacks support groups and the nearest treatment centers are separated from its residents by the longest distances on the island (Komen, 2015). Moreover, its population is older than other parts of Puerto Rico and has high percentage of women over 35 (Komen, 2015). Lastly, Southwest Puerto Rico is the poorest area in the island and has had the highest rate of depopulation between 2010 and 2020. Guánica, the site of this study, is one of the poorest municipalities in Puerto Rico with over 60% of the population below the poverty line (Cortes Chico, 202118). This area has average annual household income of just $15,000, with women earning $3,000 less (Sanabria-Leon et al., 2021). Guánica has also been the fastest depopulating municipality in the island, losing 29% of their population in 10 years. These numbers are important to understand as poverty and economic inequality shape disaster recovery.

The southwestern area had a fragile health care infrastructure even before the multiple disasters struck. In 2020, Guánica was the epicenter of the 2020 earthquakes, where thousands of earthquakes were registered in just over two months. These earthquakes have coincided with an ongoing drought since 2015, Hurricane Maria, and the current COVID-19 pandemic. These consecutive disasters increased women’s vulnerability to illnesses and other adverse disaster outcomes. For these reasons, providing social and financial support to overcome barriers to treatment and address the psychosocial needs of breast cancer patients is crucial in helping women better adjust to cancer diagnosis (Salakari et al., 2017). There is a need to understand better the specific psychosocial needs of breast cancer survivors in southwestern Puerto Rico (Castro et al., 2015b).

Research Questions

As described in the literature review, there are research gaps when understanding the coordination and integration of physical and psychological care in Puerto Rico during concurrent and consecutive disasters. We continue to lack knowledge about the needs of breast cancer patients during concurrent and consecutive disasters; how patients, nonprofit organizations, and the health care system coordinates the delivery of services; and how these services can be improved. Therefore, this project seeks to answer the three research questions that have not been addressed in previous studies:

- What are the psychosocial needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer after concurrent and consecutive disasters in Southwest Puerto Rico?

- What strategies do organizations use to meet the psychosocial needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer after concurrent and consecutive disasters in Southwest Puerto Rico?

- How can community partners improve service delivery and promote resiliency?

Sampling and Participants

We started recruitment for the survey on January 27, 2022. As of March 30th, 23 women had participated in the survey. We plan to continue recruiting participants to reach our goal of 40 respondents. To recruit participants for surveys, interviews, and focus groups we developed a convenience sampling method. The target population are women 18 years or older that were diagnosed with breast cancer in the past five years and who have received services from nonprofit organizations during concurrent and consecutive disasters. These participants are being recruited by Mabel Lassalle from Connecting Paths and Carmen Pachecho from Esfuerzate y Se Valiente through an extensive database of phone numbers of women that have received services from their organizations. Researchers have been contacting women over the phone and inviting them to participate in the study. Our sampling approach facilitates the recruitment of participants and respects patient privacy. Consent forms were sent to individuals in advance via email and explained in-person. If the recruit expressed interest in joining in the study, they were asked to choose between meeting in person with our research team or doing the survey over the phone. At the end of the survey, they were asked if they would like to participate in a follow-up interview. If they agree, a researcher from our team called them and interviewed them over the phone. As part of the survey, participants were also asked if they knew someone that might be interested in participating in the study.

In the latter stages of our project, we will be reaching out to the same sample and ask them to participate in focus groups. This focus group is intended to corroborate data and themes that emerged in our project as well as communicating the results and providing information on where to access resources and services related to housing, transportation, and psychological services.

Data, Methods, and Procedures

We administered a survey and conducted interviews and focus groups. The purpose of conducting three different data gathering methods is to triangulate data, validate our research tools, and co-produce our project with community members and stakeholders. Allowing community members to gather data provides us with access to participants and data that researchers from outside the community would otherwise not be able to acquire. Furthermore, studies suggests that involving community partners in academic research increases the recruitment of medically underserved and underrepresented minorities (Greiner et al., 201419) while effectively facilitating communication across groups (Hebert et al., 201020). As of May 2022, 23 women had participated in the survey and 10 were interviewed. Prior to recruiting participants and administering the survey, the research team conducted extensive training of community members so that they would have the capacity and expertise to administer surveys and conduct interviews of their peers. Most of the participants in this study—including the trained community members and recruited participants—are currently receiving cancer treatment and, therefore immunocompromised and highly vulnerable to COVID-19. To mitigate risk to their health, our research team has implemented several COVID-19 precautions. Participants are compensated $20 for participating in the survey. The data gathered with the surveys was analyzed using descriptive statistics with the statistical software SPSS. The qualitative data was analyzed using thematic coding with the NVIVO software.

Ethical Considerations, Researcher Positionality, Reciprocity, and Other Considerations

The Institutional Review Board declared the study “exempt” on November 24, 2021. This proposal is interdisciplinary with a nonprofit founder (Mabel Lassalle, Founder of Connecting Paths), professor in urban planning (Ivis García), and a doctoral student in urban planning (Kevin Fagundo-Ojeda). Mabel Lassalle graduated with a degree in Human Resources from the University of Puerto Rico. In 2005, Lassalle worked as Regional Director at the Alliance for a New Humanity. Originally from Puerto Rico, Dr. García studies asset-based community development and institutional support to various community groups, including nonprofits and other community actors. Displaced by Hurricane Maria in 2017, Doctoral Student Fagundo-Ojeda’s dissertation examines migratory patterns and public health disparities after disasters in Puerto Rico. Fagundo-Ojeda traveled in 2021 to southwestern Puerto Rico and met personally with Lassalle. Fagundo-Ojeda interviewed cancer patients and participated in workshops administered by Lassalle. Through this experience, Fagundo-Ojeda gathered information and developed the current study. Fagundo-Ojeda, García, Lassalle are collaborating closely with a diverse network of local organizations in Puerto Rico whose focus ranges from health care delivery, economic development, and disaster management. By creating an advisory group from distinct fields (medicine, social work, psychology, among other fields), we are honoring the expertise of those deeply involved in this work already. In addition, we hired and trained three women researchers who also met the inclusion criteria to add their lived experience to this research. This research idea was born from the experience of Connecting Paths and their identification of the need to strengthen its community networks and work with other stakeholders to improve community services and disaster resilience in Puerto Rico.

Findings

The following section describes our survey and interview findings and is divided into five subheadings detailing key findings regarding respondent’s demographic profile, experience with disasters, housing impacts, transportation limitations, and psychological service delivery.

Respondents Profile

The median age of the survey respondents was 54 years old. The youngest of the survey respondents was 39 years old and the oldest was 71 years old. In terms of educational attainment, 4.3% of the respondents had a ninth- grade education or less, 8.7% didn’t have a high school diploma, 30.6% graduated high school, 43.4% had a bachelor's degree, and 13% had a graduate degree or higher. Regarding income, 56.5% of respondents reported an income of $10,000 or less, 13% reported an income between $10,001 and $14,000, 17.5% reported an income between $14,001 and $18,000, 8.7% reported an income between $18,001 and $24,000, and 4.3% reported an income higher than $24,001. Survey data indicate that 86% of the respondents are below the federal poverty line for Puerto Rico. All respondents reported living with family members, with an average of 2.8 persons per household. Regarding the geographic distribution of our respondents, 38% live in Yauco, 27% live in Ponce, 10% of live in Guayanilla, 10% live in San German, 5% live in Peñuelas, 5% in Coamo, and 5% live in Juana Diaz.

Consecutive Disasters

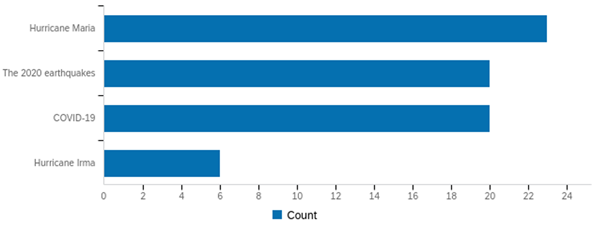

As reflected in Figure 1, all survey respondents were affected by Hurricane Maria. The earthquakes of 2020 and COVID-19 affected 87% of respondents (n=20) and Hurricane Irma affected 26% of respondents (n=6). During Hurricane Maria, 91% of respondents reported losing their electricity service, 65% of the participants reported losing water service, 30% reported that their cancer treatments were interrupted, and 21% were unable to attend cancer support groups. During the 2020 earthquakes 65% of respondents reported losing their electricity service, 34% lost their water service, 47% of respondents reported that their cancer treatments were interrupted, and 30% were not able to attend their cancer support groups.

Figure 1. Respondents Receiving Cancer Treatment and Affected by Disasters

During the COVID-19 pandemic, 34% of respondents reported having their cancer treatment temporarily interrupted. Due to tight lockdowns and intense isolation periods in the island, 50% of respondents reported that they were unable to attend cancer support groups during the COVID-19 pandemic.

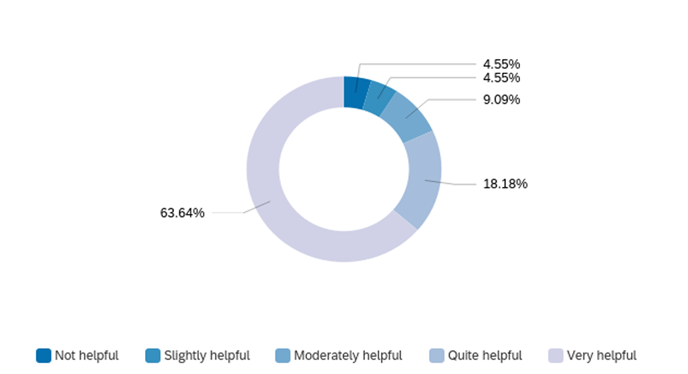

Even the temporary interruption of cancer treatments during these disasters was critical for the respondents as more than a half of participants reported being diagnosed with stage 3 breast cancer or higher. For these respondents, cancer support groups are essential when navigating their cancer diagnosis and treatment. When asked to rate how helpful cancer support groups were when navigating their diagnosis and treatment, 64% of the respondents reported that they were very helpful, 19% of respondents reported that cancer support groups were quite helpful, 8% reported support groups moderately helpful, 4.5% slightly helpful, and 4.5% reported cancer support groups were not helpful.

Housing

In terms of the structural damage that disaster caused to their homes, 60% of participants reported that their homes experienced partial structural damage during the 2020 earthquakes, compared with 26% that reported that their homes experienced partial structural damage during Hurricane Maria. Two of the respondents reported that their homes were destroyed during the 2020 earthquakes, while no respondent reported that their homes were destroyed by Hurricane Maria. Respondents were asked if they had trouble repairing their homes due financial constraints, 34% of respondents reported not having enough money to repair their homes after the 2020 earthquakes, compared to 17% that didn't have enough money for repairs during Hurricane Maria. Arguably, this might be attributed to the fact that the 2020 earthquakes and the COVID-19 pandemic occurred consecutively. People may have struggled to repair their homes due to the financial constraints caused by the destruction of the 2020 earthquakes which overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings were supported by one of our interviewees who shared the following: “Because I lost my entire home in the earthquakes I had to sleep in a shelter while receiving chemotherapy. Right after those things happened, the pandemic hit. It was a very difficult time for me.”

When asked about the impact of the disasters on their homes while receiving treatment, respondents reported that the COVID-19 pandemic had a more severe impact than Hurricane Maria. Survey data shows that 17% of respondents reported that the COVID-19 and the 2020 earthquakes had a more severe impact on their homes than Hurricane Maria. Only 1% of the respondents reported that Hurricane Maria had a severe impact on their home. We hypothesize that even though Hurricane Maria might have had an impact on the physical structure, the overlap of the 2020 earthquakes and the COVID-19 pandemic affected the social fabric of their homes, resulting in deeper and lasting impacts on members of the household and their ties to others, which, in turn their affected their access to health care and treatment. The constant tremors that lasted until March, the strict lockdowns imposed by the local governments, and the risk that COVID-19 represented for cancer patients resulted in extreme isolation for our respondents. This sentiment was echoed by one of the interviewees who said that “dealing with COVID was difficult because everyone had to be away from one another. I was all of a sudden alone in my home with an illness (cancer) and nobody to help me.”

Transportation

Survey respondents repeatedly identified transportation as one of their biggest needs they experienced while diagnosed with cancer in a disaster context. When participants were asked to rate the importance of transportation when accessing their treatment and recovering adequately from cancer in a disaster context, 91% reported it was very important for them. Transportation is particularly important in this context since Puerto Rico which lacks a reliable transportation system. In municipalities outside of San Juan, transportation systems are nonexistent, meaning that citizens rely entirely on their personal cars, or on friends and family members to move around. Most respondents reported that they depended on friends or family members to drive them to receive treatment after the disasters because they either didn’t have a car, or they were too physically impaired to drive after receiving treatment. When talking about disasters, close to 30% of the respondents reported that COVID-19 had a more severe impact on their access to transportation to receive their treatment, compared with 13% and 1% for 2020 earthquakes and Hurricane Maria respectively.

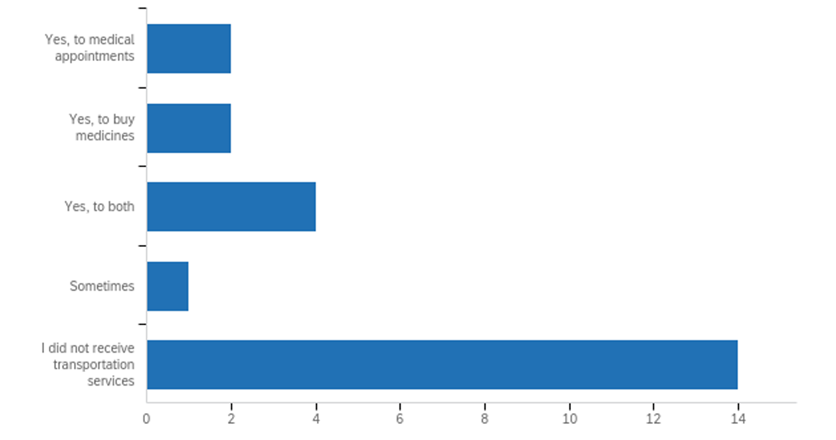

Participants who depended on friends or family members to receive cancer treatment lost access to transportation during the COVID-19 pandemic mostly due to fear of transmission and strict government policies. During the early stages of the COVID-19 lockdown, the local government enforced a policy that didn’t allow more than one person per car. Driving a person to a medical appointment meant they risked being fined or even jailed. One of the interviewees shared, “When I started chemotherapy, I couldn’t drive after receiving it because I was weak and confused. After the pandemic started it was very difficult for me to get a ride and go get treatment.” Respondents reported that most health insurances in the island included transportation in their policies. However, as reported in Figure 2, 60% of them didn’t receive transportation services from their health care insurance. Only 17% of respondents received partial transportation services from their health insurance.

Figure 2. Respondents Receiving Transportation Services From Health Insurance Providers Post-Disaster

Physiological and Psychosocial Services

Disasters can produce adverse psychological effects on people, especially on women diagnosed with a chronic illness such as cancer. In the survey data, 78% of the respondents reported that disasters made them feel anxious while they were on their cancer treatment, 65% of respondents reported having trouble sleeping, and 48% reported feeling sad or depressed. In that same vein, psychosocial services were identified by respondents as essential when diagnosed with cancer in a disaster context. As Figure 3 shows, when asked if support groups were helpful to women diagnosed with breast cancer during disasters, 63.6% responded that support groups were very helpful and 18.18% reported that support groups are quite helpful. Additionally, respondents were asked to rate the services more important to them while being on treatment after a disaster. Psychological services were chosen as the number one most important service by 44% of the respondents, followed by receiving more information about their diagnosis.

Figure 3. Respondents Who Find Cancer Support Groups Helpful

In the interviews, participants shared that these services would allow them to lower stress, feel less lonely, and provide coping mechanisms. When asked about their response to stressful situations, 52% of respondents reported that they usually have a difficult time managing stressful situations. This suggests that there is a great need for psychological services and social support during a cancer diagnosis in a disaster context. These services can increase resiliency among chronically ill patients. These findings were supported by one of our interviewees who shared the following:

Psychological help would have been the most important aspect at the beginning of the treatment for me. When I was diagnosed, I felt scared, lonely, and overwhelmed. Unfortunately, after I was diagnosed, I didn’t receive any psychological help or information on where to get it.

Conclusions

Public Health Implications

Nonprofits Play Key Role Coordinating Services

This study is concerned with the psychosocial needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer and how consecutive disasters affect their health, economic livelihoods, and overall quality of life. By doing this, our research has incorporated elements often studied separately, giving a more comprehensive picture of the needs of communities diagnosed with breast cancer. By having this information, nonprofit organizations and local governments across the island can prepare better when delivering essential services such as housing, transportation, and health care for future disaster events to chronically ill patients. In that vein, our study has investigated how chronically ill patients navigate a disaster context and the needs that accompany them. Our study indicates that the 2020 earthquakes and the COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on the housing and social ties of chronically ill patients. The 2020 earthquakes impacted the physical structure of their homes, while the COVID-19 pandemic affected their social fabric. The consecutiveness of these disasters overwhelmed their finances and complicated their recovery. As a result, almost half of the respondents reported feeling sad, depressed, or anxious after the disasters. Our research also dives into how nonprofits organizations were able to respond to these needs and provide services that improved their overall health. These gaps were filled by the collaborative efforts nonprofit organizations across the island. Respondents reported that the services provided by nonprofits were crucial to navigate their diagnosis and treatment. The most important services provided by nonprofits identified by respondents were psychological support and education regarding their cancer diagnosis and treatment. This study sheds light on the effectiveness of nonprofit services while suggesting ways to improve their delivery to chronically ill patients in future disaster contexts.

Partnerships are Essential to Address the Needs of Chronically Ill Women

This study can improve public health response after consecutive disasters by shedding light on the psychosocial needs of breast cancer patients in Southwest Puerto Rico. As Hurricane Maria, the 2020 earthquakes, and the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the treatment for hundreds of breast cancer patients in the region, our survey, interviews, and focus groups have captured topics such as psychological needs, transportation limitations, housing instability, and the economic impacts of disasters. Our findings suggest that nonprofits such as Connecting Path and Esfuerzate y Se Valiente could further build support groups into their post-disaster service delivery to breast cancer patients. The objectives of this attending breast cancer support groups should be twofold. First, to provide emotional support so that women can manage feelings of anxiety and depression related to their diagnosis and connect with others receiving cancer treatment and survivors. Second, to provide information and assistance on some of the opportunities identified in this study, such as transportation provided by medical insurance, assistance programs to repair homes damaged by disasters, and psychosocial options, among other topics. Through continuous interaction, supportive groups can also identify further reasons for temporary interruptions during disasters and figure out how to satisfy the needs of women. Connecting Path and Esfuerzate y Se Valiente already partner with organizations such as Mujer Latina Emprende, la Sociedad del Cáncer del Seno, the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation and the University of Puerto Rico Comprehensive Cancer Center, among others that provide integrated services, including mobile breast cancer screenings and workshops on emotional resilience and economic development. However, they could benefit from creating new partnerships with other nonprofits, churches, and trusted physicians, to coordinate services.

Limitations and Strengths

One of the limitations of the findings reported here is that they are based on a relatively small survey (n=23) and interviews (n=10) samples. As mentioned above, our community-based methods for developing the survey with input from community partners and training residents to conduct the survey and interviews took more time than we expected. However, we have learned from this process that one of the primary strengths of this project is that it was born from a community-based research partnership in which researchers and partners are co-producing questions. We have designed this project using an advisory group and training women to conduct community-based research (Israel et al., 200521). The advisory group was consulted to inform the creation of the survey and interview questions, the participant recruitment, data collection, and analysis. This study also engages residents as researchers to build their capacity to conduct other research projects in the future. Women researchers and community members with lived experience of being cancer patients and receiving services during disaster events were trained in surveys, interviewing, and other techniques.

Future Research Directions

We aim to complete our survey by July 2022 and conduct statistical analysis of the survey data in the following months. We will complete the additional interviews during the same time period. Women currently completing the surveys and interviews will be asked to participate in future focus groups which will investigate their views of how to improve service delivery.

Dissemination Plan

We will present findings from our investigation to staff and clients at Connecting Paths and its partner organizations Esfuerzate Y Se Valiente, Mujer Latina Emprende, la Sociedad del Cáncer del Seno, and the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. To disseminate data among academics, we will rely on various conferences, including those sponsored by the Natural Hazards Center, the Association Collegiate Schools of Planning (ACSP), and the American Planning Association. In addition, we will also conduct a bilingual webinar on August 4, 2022, and advertise via Planners for Puerto Rico, Caribbean Preparedness and Reponse Inc., Planners of Color Interest Group, Puerto Rican Agenda, Planners Network, ACSP Climate, Sociedad de Planificadores, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, among other organizations. We will record these webinars, post them on YouTube, and promote them on social media. As part of our research study, we have collected emails from more than 250 nonprofit organizations in Puerto Rico that might be interested in this topic; we will create a special webinar for them (only in Spanish). The presenters will be the community partners and women researchers. Furthermore, we will provide some funds for to our co-researchers and community partners to use to disseminate the findings as they see needed. Finally, we will publish the survey and interviews on DesignSafe, a web-based research platform of the Natural Hazards Engineering Research Infrastructure (NHERI) Network, so that other researchers can access it.

References

-

Rodriguez-Rabassa, M., Hernandez, R., Rodriguez, Z., Colon-Echevarria, C. B., Maldonado, L., Tollinchi, N., Torres-Marrero, E., Mulero, A., Albors, D., Perez-Morales, J., Flores, I., Dutil, J., Jim, H., Castro, E. M., & Armaiz-Pena, G. N. (2020). Impact of a natural disaster on access to care and biopsychosocial outcomes among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 10376. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66628-z ↩

-

Castro, E. M., Asencio, G., Quinn, G. P., Brandon, T., Gwede, C. K., Vadaparampil, S., Simmons, V., McIntyre, J., & Jiménez, J. (2017). Importance of and Satisfaction with Psychosocial Support among Cancer Patients and Survivors in Puerto Rico: Gender, Health Status, and Quality of Life Associations. Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal, 36(4), 205–211. ↩

-

Torres-Cintrón, M., Ortiz, A. P., Pérez-Irizarry, J., Soto-Salgado, M., Figueroa-Vallés, N. R., De La Torre-Feliciano, T., Ortiz-Ortiz, K. J., Calo, W. A., & Suárez-Pérez, E. (2010). Incidence and mortality of the leading cancer types in Puerto Rico: 1987-2004. Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal, 29(3), 317–329. ↩

-

Sanabria-Leon, W., Henrici, J., Torres, M. G., Cardona, A., Fairbairn, A., & Eaton, E. (2021). Cascading Disasters, Gender, and Vulnerability in Southwestern Puerto Rico. Natural Hazards Center Public Health Grant Report Series, 13. Boulder, CO: Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/cascading-disasters-gender-and-vulnerability-in-southwestern-puerto-rico ↩

-

Sahar, L., Nogueira, L. M., Ashkenazi, I., Jemal, A., Yabroff, K. R., & Lichtenfeld, J. L. (2020). When disaster strikes: The role of disaster planning and management in cancer care delivery. Cancer, 126(15), 3388–3392. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32920 ↩

-

Gorji, H. A., Jafari, H., Heidari, M., & Seifi, B. (2018). Cancer Patients During and after Natural and Man-Made Disasters: A Systematic Review. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 19(10), 2695–2700. https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.10.2695 ↩

-

Richards, M. A., Westcombe, A. M., Love, S. B., Littlejohns, P., & Ramirez, A. J. (1999). Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review. Lancet (London, England), 353(9159), 1119–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02143-1 ↩

-

Man, R. X.-G., Lack, D. A., Wyatt, C. E., & Murray, V. (2018). The effect of natural disasters on cancer care: A systematic review. The Lancet Oncology, 19(9), e482–e499. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30412-1 ↩

-

Nikbakhsh, N., Moudi, S., Abbasian, S., & Khafri, S. (2014). Prevalence of depression and anxiety among cancer patients. Caspian Journal of Internal Medicine, 5(3), 167–170. ↩

-

Castro, E. M., Jiménez, J. C., Quinn, G., García, M., Colón, Y., Ramos, A., Brandon, T., Simmons, V., Gwede, C., Vadaparampil, S., & Nazario, C. M. (2015b). Identifying clinical and support service resources and network practices for cancer patients and survivors in southern Puerto Rico. Supportive Care in Cancer, 23(4), 967–975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2451-5 ↩

-

Salakari, M., Pylkkänen, L., Sillanmäki, L., Nurminen, R., Rautava, P., Koskenvuo, M., & Suominen, S. (2017). Social support and breast cancer: A comparatory study of breast cancer survivors, women with mental depression, women with hypertension and healthy female controls. The Breast, 35, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2017.06.017 ↩

-

Shen, A., Qiang, W., Wang, Y., & Chen, Y. (2020). Quality of life among breast cancer survivors with triple negative breast cancer—Role of hope, self-efficacy and social support. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 46, 101771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101771 ↩

-

Ristevska-Dimitrovska, G., Filov, I., Rajchanovska, D., Stefanovski, P., & Dejanova, B. (2015). Resilience and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 3(4), 727–731. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2015.128 ↩

-

García, I., Chandrasekhar, D., Ganapati, N. E., Fagundo-Ojeda, K., Velazquez-Diaz, J., Witkowski, K., & Rivera-Miranda, P. (2021). Nonprofit Response to Concurrent and Consecutive Disaster Events in Puerto Rico. Natural Hazards Center Public Health Grant Report Series, 9. Boulder, CO: Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/nonprofit-response-to-concurrent-and-consecutive-disaster-events-in-puerto-rico ↩

-

Quarantelli, E. (1988). Disaster crisis management: A summary of research findings. Journal of Management Studies, 25. ↩

-

Smallman, C., & Weir, D. (1999). Communication and cultural distortion during crises. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 8(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653569910258219 ↩

-

Susan G. Komen. (2015). Community Profile Report. https://www.komen.org/breast-cancer/facts-statistics/breast-cancer-statistics/ ↩

-

Cortes Chico, R. (2021, September 5). La despoblación es más intensa en el sur de Puerto Rico. El Nuevo Dia. https://www.elnuevodia.com/noticias/locales/notas/la-despoblacion-es-mas-intensa-en-el-sur-de-puerto-rico/ ↩

-

Greiner, K. A., Friedman, D. B., Adams, S. A., Gwede, C. K., Cupertino, P., Engelman, K. K., Meade, C. D., & Hébert, J. R. (2014). Effective Recruitment Strategies and Community-Based Participatory Research: Community Networks Program Centers’ Recruitment in Cancer Prevention Studies. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 23(3), 416–423. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0760 ↩

-

Hebert, J. R., Brandt, H. M., Armstead, C. A., Adams, S. A., & Steck, S. E. (2010). Interdisciplinary, Translational, and Community-Based Participatory Research: Finding a Common Language to Improve Cancer Research: Figure 1. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 18(4), 1213–1217. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1166 ↩

-

Israel, B. A., Parker, E. A., Rowe, Z., Salvatore, A., Minkler, M., López, J., Butz, A., Mosley, A., Coates, L., Lambert, G., Potito, P. A., Brenner, B., Rivera, M., Romero, H., Thompson, B., Coronado, G., & Halstead, S. (2005). Community-Based Participatory Research: Lessons Learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environmental Health Perspectives, 113(10), 1463–1471. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.7675 ↩

Fagundo-Ojeda, K, García, I., & Lassalle, M. (2022). Planning for Post-Disaster Needs of Women With Breast Cancer in Puerto Rico (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 24). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/planning-for-post-disaster-needs-of-women-with-breast-cancer-in-puerto-rico