Cascading Disasters, Gender, and Vulnerability in Southwestern Puerto Rico

Publication Date: 2021

Executive Summary

Overview

Puerto Ricans, especially those living in the southwestern region of the island, are disproportionately impacted by worsening natural hazards that lead to multiple compounding disasters. Since 2017 these events have proliferated, and their damages endure. In addition, disasters are overwhelming the already weakened Puerto Rican healthcare system, which has an inadequate workforce and is in debt. This, in turn, contributes to southwestern Puerto Ricans’ distrust of government and private sector disaster response and recovery. To understand the impact of these cascading disasters in the southwest region of Puerto Rico, this study used a gender and intersectional approach to disasters analyzing the idea that multiple oppressions of social identity co-occur among members of racial and gender minority groups, and that discrimination and inequality are compounded along geographies of class and disability status. We use a gender and intersectional lens on disaster to build on that scholarship, examining the effects of power relations and discriminatory conditions during worsening disaster conditions and in the conventional responses to them. In the case of the disaster-impacted residents in the southwestern part of Puerto Rico, this lens contributes to a better understanding of healthcare difficulties. By studying disasters using a gender and intersectional approach, we can deepen what is being learned about the ways disasters affect residents of southwestern Puerto Rico and provide recommendations about how to better prepare and respond.

Research design

This study employed a mixed methods sequential study that employed surveys, interviews, and participant observation site visits to collect primary data. Our mixed methods approach began with two surveys (individual/household and organization), incorporated in-depth interviews to contextualize and expand on the data gathered in the surveys, and concluded with two weeks of participant observation in key locations and communities. Mixed methods allowed the research team to best understand and contextualize narratives of individual and community experiences related to health care access in the context of cascading disasters. We conducted mixed methods data collection remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic from January to May 2021 and through an onsite field component in June 2021, after conditions for respondent and researcher safety permitted.

Research Questions

The research questions that guided the data analysis were: (a) how does the Puerto Rican healthcare system interact with disaster risk and recovery, and how are cascading disasters affecting that system? (b) how do disasters in Puerto Rico interact with the distrust between communities and institutions, and how does this affect access to healthcare services? (c) do gendered health challenges emerge because of interactions between the health system and disasters? and (d) what strategies do vulnerable communities develop to prepare for future compound natural hazards?

Implications and Conclusion

Our findings suggest differences in gender and disability status among southwestern Puerto Ricans that indicate that they are relatively more vulnerable to their region’s cascading disasters. Our preliminary analysis of the interviews found that public spaces such as hospitals, schools, offices, fields, churches, and marketplaces comprise a dynamic context where vulnerability and safety are exchanged through systematic response. Public health policy needs to consider, with gender-responsive planning, where people seek shelter or are compelled to remain. In addition, interviews identified challenges to healthcare access: (a) limited access to specialized and primary care; (b) travel time to the San Juan metropolitan area to attend medical appointments; (c) the uneven application of basic health and safety protocols; (d) absence of a continuously functioning communications infrastructure; and (e) absence of mental health supports that impact patients, healthcare personnel, and first responders.

Our household/individual survey showed that there was a significant concentration of household units with people with disabilities at the lowest income levels. Data from our in-depth interviews clarified that the impact on people with disabilities on the household is a constant demand on human and financial resources. The limitations on mobility and resources for households where people have disabilities need to be considered when devising pre- and post-disaster healthcare policy.

Our organizational representative survey found that federal funds are highly concentrated on the largest of healthcare organizations, which are located in urban centers. Importantly, interview data shows that access to health care immediately following a disaster was regularly sought and provided by small local organizations with strong emotive ties to the community.

Introduction

Cascading Disasters

Puerto Ricans, especially and disproportionately those living in the southwestern region of the island, experience cascading disasters. Cascading disasters might occur because of technical or resource issues or because of continuing and worsening socioeconomic inequalities and relative vulnerabilities (Pescaroli & Alexander, 20151). In Puerto Rico, these multiplying events cause and lead to other events, which relate both to natural hazards, including infectious diseases, and distrust of both governmental or private sector response and recovery efforts.

The distinct events that together form these cascading disasters are:

- Epidemiological alerts due to the increase in cases related to the transmission of vector viruses including dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika. The last is of grave concern for pregnant women and those seeking to become pregnant because of the likelihood of transmission to the fetus leading to microcephaly as a congenital disability.

- The ongoing economic crisis that began in 2015 (Cordero-Guzman et al., 20152).

- Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017.

- An earthquake swarm of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of quakes that began in December 2019 and continued through 2020 (De Dios Santos, 20203; U.S. Geological Survey [USGS], 20204).

- A political crisis in 2019, when gender-focused social movements combined with threats of impeachment and accusations of fraud regarding Hurricane Maria aid money led to the resignation of the governor, without any prearranged successor.

- The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of which is not yet adequately captured in scholarship but has gendered healthcare effects, including in Puerto Rico (Bárcena, 20215; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean [ECLAC], 20206, 20217).

Impact of Cascading Disasters on the Puerto Rican Healthcare System

Puerto Rico health services have been worn down by these disasters that have increased in quantity, type, and intensity during the six years since 2015 across the island, in particular its southwestern region, and have become part of the mistrusted response and recovery efforts. As other researchers have noted (Niles & Contrera, 20198; Roman, 20159), Puerto Rico’s healthcare system is collapsing in on itself both financially and through a drain of qualified health professionals in large part because of the unequal relationship Puerto Rico has as a Territory of the United States.

These conditions are due to (a) a higher than average percentage of no- and low-income residents; (b) a relatively high cost of living on the island in part due to U.S. federal trade requirements; (c) persistent nutrition and health-related problems that have been inadequately addressed; (d) reduced facilities and staffing of health services over the past decades across Puerto Rico as part of healthcare privatization (known as La Reforma); and (e) the increased use of managed care resulting in part from limitations in the population’s access to Medicare program coverage. In addition, the massive debts accruing in Puerto Rico, in large part to cover healthcare costs and related inadequate supply of medical resources and personnel, worsen islanders’ vulnerability to future disasters (Perreira et al., 201710).

According to Benavides, the U.S. healthcare system is predominately privatized yet heavily subsidized, is the most expensive system in the world per person, and within it, “health care is a privilege, not a right, available to those who overcome economic inequalities and significant asymmetrical information” (2020, p. 187). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are six key components of a functioning health system: leadership and governance; health information systems; health financing; human resources for health; essential medical products and technologies; and service delivery (WHO, 201011). As disasters proliferate in Puerto Rico, all these components are impacted, and individuals suffer.

Puerto Ricans pay into the U.S. public programs of Social Security (an employment-paid trust fund paid out as retiree income and support for those with documented disabilities) and Medicare (the U.S. system of health coverage for those 65 years and older and younger people with specific and documented health conditions) (Benavides, 202012; Mach, 201613).

While U.S. federal eligibility regulations differ somewhat from those of the Puerto Rican government (Mach, 2016), Puerto Ricans nevertheless disproportionately qualify for these federal health programs as well as those for the extreme poor, Medicaid and the Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP). This disproportionate qualification is due to (a) the percentage of no- and low-income residents, affected further by the relatively high cost of living on the island, in part, due to U.S. federal trade requirements, and the related nutrition and health-related problems, particularly among children and youth; (b) the island’s aging population—the majority of whom are older women; and (c) the relatively high percentage of Puerto Ricans with a diagnosed disability (Benavides, 2020; Perreira et al., 2017).

However, while Puerto Ricans, as U.S. citizens, contribute their share in the form of tax withholdings to the U.S. healthcare infrastructure, in return, they receive less of a share per person than do any of the 50 states or the District of Columbia (Roman, 2015). As a result, these means-tested subsidized programs are grossly insufficient to meet the needs of Puerto Ricans. In recent decades, funding has decreased for healthcare facilities and staffing across Puerto Rico as part of privatization trends (La Reforma) and the rise toward managed care municipal diagnostic and treatment centers. Many of these centers were defunded across Puerto Rico, although some were converted to nonprofits and of those some remain eligible for public funding while others remain private—if charitable—in operation (Perreira et al., 2017, p. 8). As a result, the Puerto Rican healthcare system itself has become a disaster and one that worsens others. Even as they share with other islanders ongoing high poverty rates and chronic health problems, those living in Puerto Rico’s southwestern communities that are being hit hardest by earthquake swarms, infectious diseases, and multiple hurricanes, must also struggle to obtain health services.

Importantly, communities in southwestern Puerto Rico nevertheless have a well-developed autogestion defined as self-assembly networks has been used to fill gaps in the healthcare system. The network has firm roots in the environmental justice movements in which women have played pivotal leadership roles in the municipalities of Ponce, Adjuntas, and Guayanilla (García-López, 201814). These networks of self-assembly are robust political movements aimed at making substantial changes in a “politics of survival” to fill in areas vacated by the state (Tormos-Aponte, 201815). Moreover, given the perception in the region of abandonment by the government in the wake of disasters (García López, 202016), self-assembly movements have become central to the provision of essential services, including the healthcare system infrastructure (Lloréns & Stanchich, 201917).

Using a Gender and Intersectional Approach to Disaster

Analysis for this project takes a gender and intersectional approach to disaster (Bradshaw, 201318, 201419; Enarson et al., 201820; Erman et al., 202121; Henrici, 201022, 201523; Henrici & Helmuth, 201024; Henrici et al.,201225; Neumayer & Plümper, 200726; Yadav & Kelman, 201927. Intersectionality expanded as a concept among antiracist Black feminist scholars and activists during the 1980s through the work of legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (198928; 199129) among others (Carastathis, 201630; Collins, 201131). A gender and intersectional approach to disaster is built on the idea that multiple oppressions of social identity co-occur so that, for those who are both members of racial and sexual minority groups, and identify or present as women, discrimination and inequality are compounded along geographies of class and disability status (Carastathis, 2016; Lloro-Bidart & Finewood, 201832).

Extensive disaster scholarship meanwhile finds that those, such as the residents of southwestern Puerto Rico, who have less wealth, fewer resources, and more experiences with discrimination than those who are more privileged because of attitudes and norms regarding gender and race within a wider society—are relatively more vulnerable during disasters. In the aftermath of disasters, these people also experience poorer health conditions, socioeconomic hardships, and potentially disabling illnesses and injuries (Gaillard, 201033, p. 222; also see Gaillard, 201934; Wisner et al., 200435).

A gender and intersectional lens to disaster builds on that scholarship, to examine the effects of power relations and discriminatory conditions in worsening disaster conditions and in conventional responses to them (Tierney, 201436). In the case of the disaster-impacted residents in the southwestern part of Puerto Rico, this lens contributes to a better understanding of healthcare difficulties (Caraballo-Cueto & Godreau, 202137). By studying disasters using a gender and intersectional approach, we can deepen what is being learned about the ways disasters affect residents of southwestern Puerto Rico and provide recommendations about how to better prepare and respond.

Current Study

Research on Puerto Rico gender-responsive healthcare policy reform in a context of cascading disasters is needed, yet largely lacking. Our project seeks to help fill this gap and contribute to the scholarship that does exist by generating applicable policy recommendations to be founded on our analysis of what individuals in the most disaster-affected region of Puerto Rico, the southwest, say they need to be able to access healthcare services (Gaillard et al., 201938; Louis-Charles et al., 202039). “Ultimately, examining ‘cascading disasters’ and ‘cascading effects’ through a gender lens demonstrates the importance and advantages of putting people at the center of disaster-related work” (Yadav & Kelman, 2019). To meet that objective, we conducted a mixed methods study using a gender and intersectional framework as described in the next section. Such an approach focuses on structural power relations at household, community, institutional, and national levels in general and, within disaster studies, examines differentiated disaster vulnerabilities tied to social norms and socioeconomic and political inequalities.

Methods

We employed a mixed methods sequential study that employed surveys, interviews, and participant observation site visits to collect primary data. Our mixed methods approach began with two surveys (individual/household and organization), incorporated in-depth interviews to contextualize and expand on the data gathered in the surveys, and concluded with two weeks of participant observation site visits to key locations and communities. Mixed methods allowed the research team to best understand and contextualize narratives of individual and community experiences of health care access in a context of cascading disasters. We also collected secondary data through literature and census reviews.

Research Questions

- How does the Puerto Rican healthcare system interact with disaster risk and recovery, and how are cascading disasters affecting that system?

- How do disasters in Puerto Rico interact with the distrust between communities and institutions, and how does this affect access to healthcare services?

- Do gendered health challenges emerge because of interactions between the health system and disasters?

- What strategies do vulnerable communities develop to prepare for future compound natural hazards?

Study Site Description

Some of these disasters were the result of large-scale, sudden-onset natural hazards, while others are ongoing, and a few are more socioeconomic or political in character than others. Autogestion, working in conjunction with other environmental movements, illuminates how environmental injustices correlate directly to the vulnerabilities exacerbated by these disasters (Pastor et al., 200640). Together, these layered disasters generate increased vulnerability even further among marginalized people and communities and exhaust Puerto Rico’s healthcare system. Moreover, the outcomes from these disasters are differentiated among Puerto Ricans so that not all individuals by identities such as age, gender, and disability status have been affected equally. Those living in the southwestern region of Puerto Rico have been disproportionately affected.

Both as an outcome and as an influence on these conditions is the increased out-migration from the U.S. territory, an example of what Palinkas (202041) defines as “climagration,” or emigration because of combined natural events, income disparities, and socioeconomic vulnerabilities. That emigration, combined with lower birth rates, reduced the population of Puerto Rico between 2010 and 2020 by 11.8% to 3.3 million, according to the U.S. Census Bureau 2020 decennial census data (Gamboa, 202142). Since 2020 data have not all been released as of this report (U.S. Census Bureau, 202043), using the Puerto Rico Community Survey (a targeted part of the American Community Survey) 1-Year Estimates for the most recent data (2019), it appears that the island population is not only shrinking but also aging, with just 17.9% of the population under 18 years of age and 21.3% at 65 years and above, with the median age of 43.1 years old (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019a44, 2019b45, 2020).

Older Puerto Ricans have age-specific health concerns worsened by the disasters that keep hitting their homes (Downer & Markides, 201846); at the same time, younger Puerto Ricans also face health problems: significant proportions of Puerto Ricans under age 65 were living without health insurance (9.5%) and identified as living with a disability (14.9%) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019b), while over one-third of Puerto Rican adults (38.1%) of any age (15+) were reported in 2017 to have some type of disability (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 201747). In 2016, disabilities in Puerto Rico were reported as roughly equal by gender but, in terms of age, were highest among Puerto Rican boys and men under 75 and among women 75 years and older (Yang-Tan Institute on Employment and Disability, 201648).

In addition, 43.1% of Puerto Rico’s population in 2019 was living in poverty, almost quadruple the U.S. rate of 11.8%. The median household income of Puerto Rico was $20,166, which is about one-third of the national median income of $60,293. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, more than one-third of adult residents in Puerto Rico experience food insecurity (Keith-Jennings, 202049). Poverty, unemployment rates, food insecurity, disability, and diabetes rates are all higher in Puerto Rico when compared to the mainland U.S. population.

According to the most recent data, the average annual household income in the region within the municipalities of Ponce, Adjuntas, and Guayanilla is just above $15,000, with women earning $3,000 less on average (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). In the study region, employment is concentrated, in order of importance, in the fields of educational services, healthcare and social assistance services, retail, and public administration.

While most of the island topography is mountainous (60%), the southwestern part of Puerto Rico is much more so. Cerro Punta, the island’s highest peak, is located between Jayuya and Ponce, in the western part of the central mountain range. The southwest is part of the island’s high density of hydrographic network, but it is also the driest and hottest region of the island due to the central mountain range that limits the flow of water from the north (Gobierno de Puerto Rico, n.d.50; USGS, n.d.51). There is only one city (Ponce) in southwestern Puerto Rico.

Mixed Methods Primary Data Collection

Surveys

For the quantitative component of our study, we fielded two bilingual surveys from March to May 2021. One survey targeted individuals and households and the other targeted representatives from organizations that provided any health-related services during the most recent natural disaster events (Hurricanes Irma and Maria, earthquakes, and the COVID-19 pandemic). Most of the respondents who completed either survey answered using the Spanish-language version. Both survey instruments we employed used non-probability sampling and asked a mixture of demographic and subjective questions. Neither survey required mandatory responses to any of the questions.

Household/Individual Survey

The first survey was a confidential online social survey of households or individuals (n=190). Respondents were individuals residing in the southwestern part of Puerto Rico who answered just for themselves or as members of households above the age of 18. The survey excluded individuals under the age of 18 and those not residing in southwestern Puerto Rico.

This survey drew on a convenience sample. The questionnaires were distributed via a boosted link on a Facebook page that we established both to reach our sample, since the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic prevented face-to-face recruiting and surveying, and to disseminate the final report (https://www.facebook.com/CDGVSPR). Given the size of the sample, the survey data was analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Ninety percent of the respondents who answered the gender identification question identified as female. The sample of respondents was of individuals mostly middle-aged with 38% self-identifying as 47–56 years of age, 30% as 57–66 years of age, 18% as 46 years old and under, and 14% as 67 years old or older. Our sample over-represents middle-aged and young people with access to social media. We have no race or ethnicity information to share as all survey respondents chose not to provide it.

Organizational Representative Survey

The second survey was a confidential online survey of organizational representatives (n=50). Respondents were above the age of 18 and were either individuals responding for their employers or self-employed. The organizations and professionals were screened to include health-associated service providers working in southwestern Puerto Rico. Individuals who were under 18 or not employed or self-employed in organizations that provide health-associated services to communities in southwestern Puerto Rico were excluded from the survey. The survey was distributed via recruitment emails to institutions in the southwest region of Puerto Rico. Given the size of the sample, the survey data was analyzed using descriptive statistics.

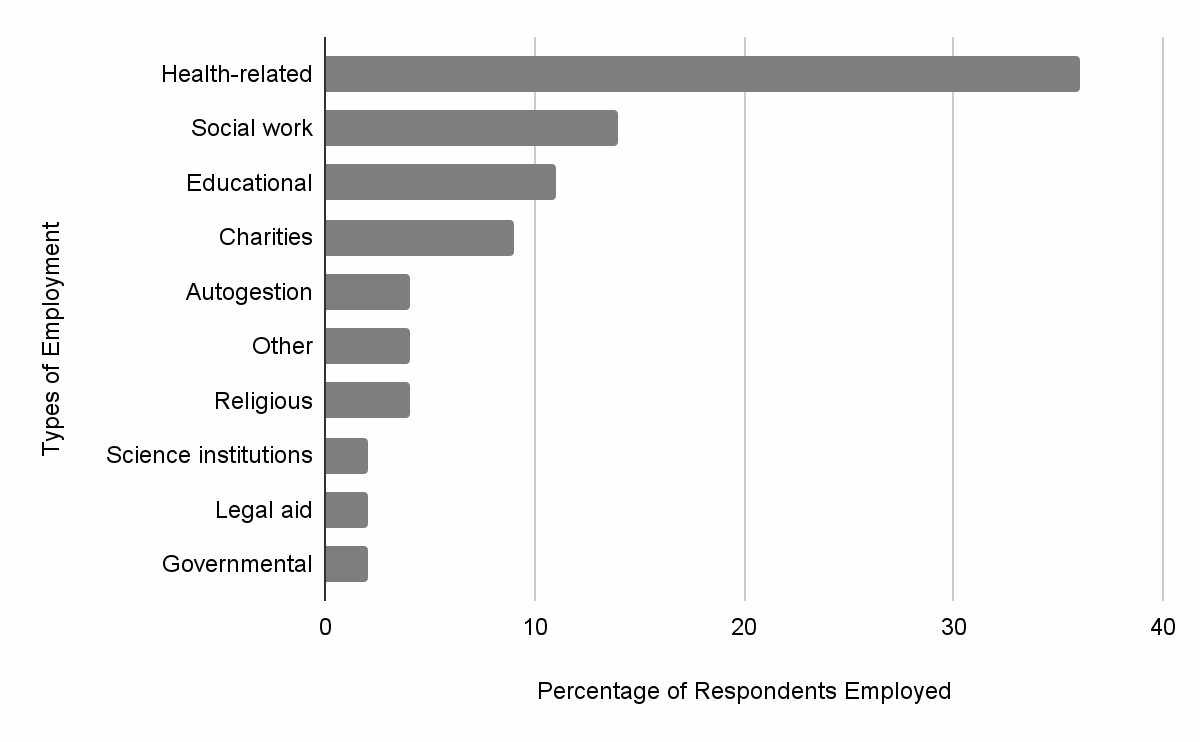

As Figure 1 shows, the second survey respondents were employed in health-related organizations, social work, education, charities, autogestion organizations, nonprofits/non-governmental organizations (NGOs), religious organizations, science institutions, legal aid, and governmental agencies. Most of the respondents had been classified as essential workers (87%). Most organizations and agencies represented (76%) provide services for victims of gender-based violence. Most organizations and agencies (52%) provide services to 500 or more recipients per month while 33% provide services to 100–499 recipients per month. Organizations and agencies that provided services to 100 or fewer recipients ranged among those that served 1–25, 26–50, or 51–99 recipients; each category comprised 5% of survey respondents.

Figure 1. Organizational Representatives Employment Sector

Interviews

As part of the qualitative component of our project, we remotely conducted 20 unstructured interviews in Spanish through May 2021, most of which were more than one hour in length. Remote interviews were held via the video meeting service Zoom, primarily on laptops, although some respondents used their cell phone cameras.

The interviews provide rich individual narratives of health service provision and health service access. They are the most complex data source we collected to answer the research questions our study posed as they purposefully elicited broad subject-focused narratives of experiences before and after natural catastrophic events that limited or affected individual access to health services and the challenges to the provision of health services. Our questions were purposefully open-ended, experience focused, and organized to draw out the strategies related to access, distribution, and mitigation of the consequences of natural catastrophic events in the daily lives of the subjects.

Given our interest in how the healthcare system interacts with disaster risk and recovery, and how distrust between communities and institutions shapes healthcare access, we invited participants who held organizational roles in area hospitals and health services as well as those serving in other public service roles. This inclusion criteria differs from our survey criteria as it sought to specifically explore the first two research questions posed by our study. Recruitment was done through a recruitment email that explained the Institutional Review Board (IRB) exception, the title of the project, and a short description of the investigaton. In some cases, respondents were referred by others who were interviewed previously. There were, in addition, respondents who were recruited via surveys and became interview participants. Interviewees were incentivized with a $35 gift card. Informed consent was obtained prior to each interview by reading an informed consent script and requiring oral acceptance of participation. We have successfully conducted interviews thus far with physicians (geriatric specialists, epidemiologists, hospice care, and a general practitioner), nurses, physical therapists, public health administrators, a police officer, and community organizers. As described below, interviews are transcribed, coded, and analyzed using two different qualitative software packages.

Field Work Site Visits and Interviews

To get a broader set of interviewees from diverse class backgrounds and to gain a sense of the physical infrastructure damage and recovery, we conducted ten onsite interviews and 7 site surveys. Site surveys allow us to see infrastructure access issues firsthand, the in situ use of infrastructure, and the respondents’ lived experience with natural disaster damage to homes and public structures. Our site surveys covered the three sites from which our study drew in southwestern Puerto Rico and included the most impacted areas of Guanica, Guayanilla, Ponce, and Utuado, as well as a survey of the fully solar-powered town center of Adjuntas. In addition, we surveyed existing disaster relief infrastructure in Ponce.

Secondary Data Collection

In addition to these primary data collection and analysis methods, we conducted a secondary data collection and literature review. American Community Survey data from 2019, Puerto Rico Community Survey data from 2020, and the decennial U.S. Census disaggregated data for Puerto Rico from 2020 were reviewed. We also examined extensive scholarship concerning gendered disasters and vulnerabilities, the Puerto Rican public health system and related governmental policies, pertinent infectious diseases, mental health issues, and community responses and coping strategies including autogestion efforts. Media coverage concerning gender-based violence and differentiated health access also were part of our literature review.

Data Analysis

To analyze the responses from both surveys, each had to be recast into a single language survey. Since most responses were submitted using the Spanish-language version, all responses were translated into Spanish prior to any analysis for consistency. For our analysis of interviews, we uploaded the recordings into Trint (an automated multi-lingual transcription service), to transcribe the recordings in Spanish and generate a translation of them into English. We are currently cleaning the transcriptions and translations of errors and removing personal identifying information. Once transcriptions and translations have all been cleaned and rendered confidential, the texts will be uploaded into MAXQDA2020, a statistical analysis software. We will heuristically and categorically code and recode the transcriptions to ascertain patterned responses to disasters and health service access and provision, with attention to differentiated responses concerning gender and any other indicators of relatively greater vulnerability.

Researcher Positionality, Reciprocity, and Other Ethical Considerations

As a collaboration between researchers from multiple institutions, disciplinary specialties, and cultural contexts, the results of this study reflect an interplay between multiple theoretical, methodological, and analytical approaches. Putting together spatial, medical, gender, and intersectional expertise, our study is nourished by a broad set of area expertise. Puerto Rican-based researchers working together with U.S. mainland researchers has resulted in multiple convergent frameworks for the research problem and its analysis. The group is composed of five primary researchers who identify as women and speak Spanish at different levels of fluency. Importantly for the issue of community trust and evident empathy, three of the researchers are Puerto Rico-based researchers. To mitigate the ethical challenge through the research process, as a team we worked to establish relationships of empathy and trust among the participants. This project thus uses both a convergence approach and an intersectional gender lens with which to recruit, interview, analyze, and report on this research and maintain the highest standards of research ethics with a sensitivity for conducting research with Puerto Ricans as disaster survivors. In terms of data collection, interviewing those who have lived through traumatic experiences is challenging, most particularly through a virtual platform. In this mode, it is an ethical challenge to appropriately support people who narrate and thus replay their traumatic experiences.

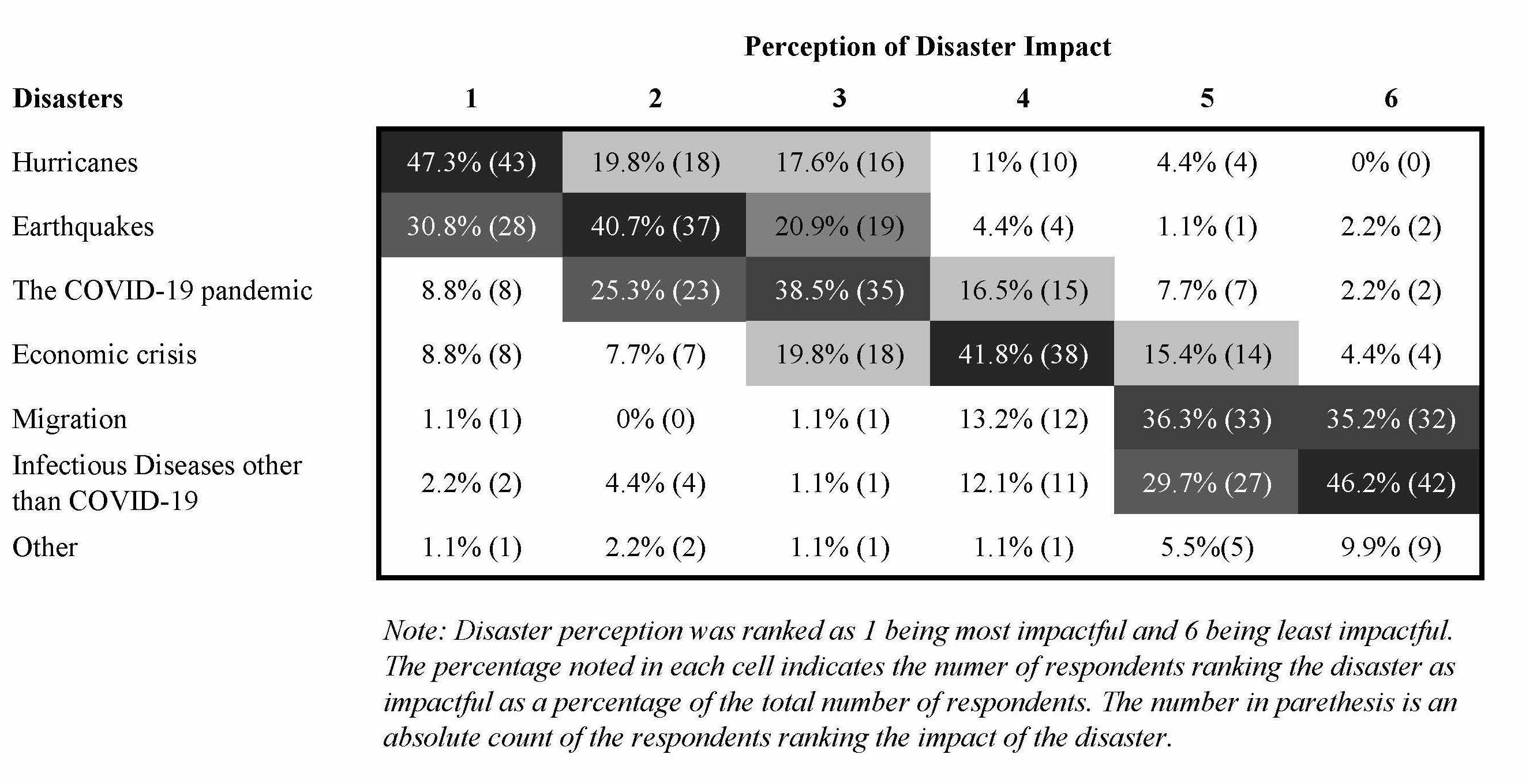

Table 1. Disaster Impact Perception of Respondents from Southwestern Puerto Rico

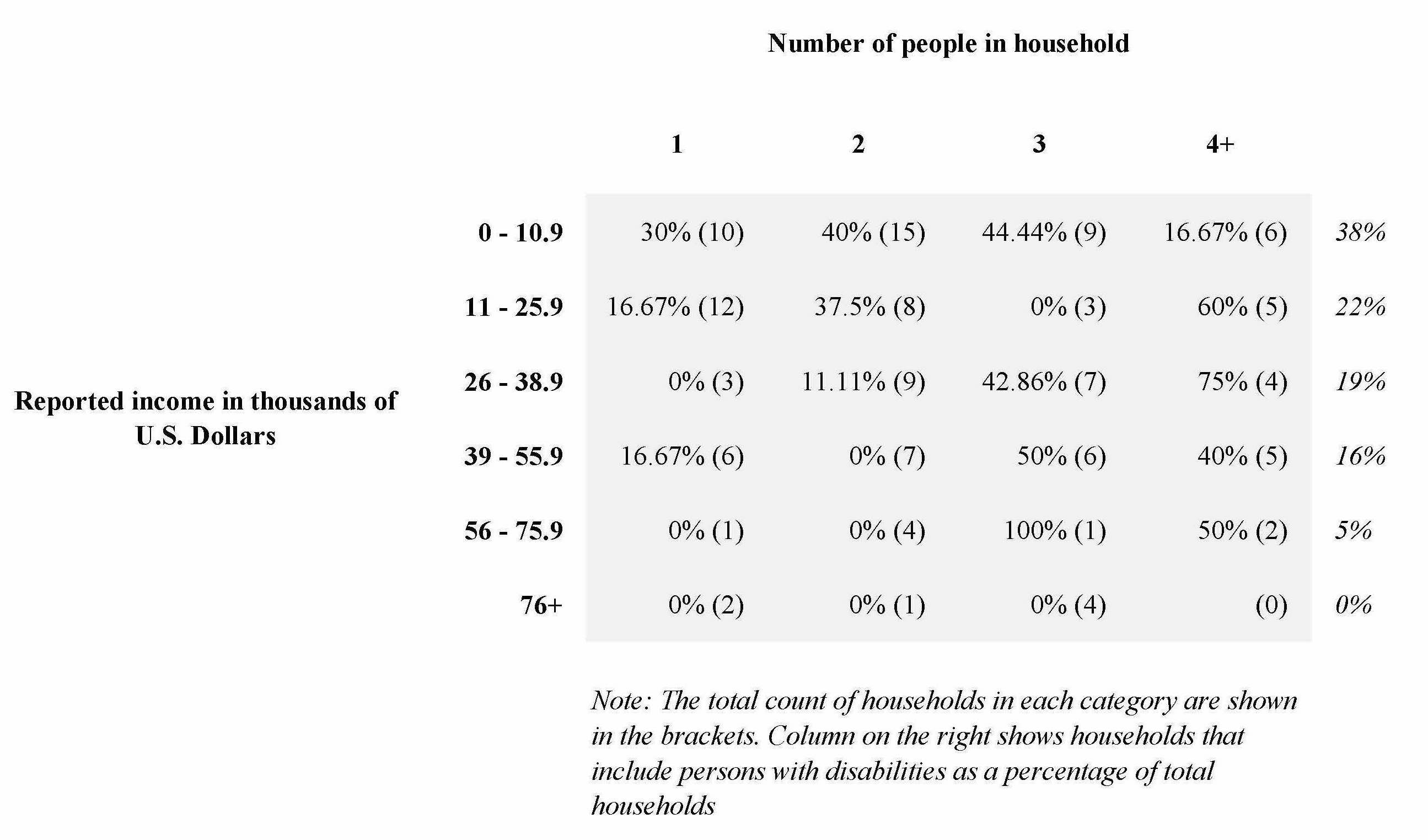

Our study found multiple vulnerabilities present in southwestern Puerto Rico: age, disability, gender, travel time to health care facilities, and household income. One notable vulnerability, as seen in Table 2, was the concentration of Households including Individuals with Disabilities (HIDs) at the lowest income bracket earning below $10,900 annually regardless of the household size (38%). For those earning less than $25,900, the likelihood of having a HID is much higher (60% of our household sample) than for those with larger incomes (40% of our sample) regardless of household size.

Table 2. Households Including Individuals with Disabilities and Reported Income

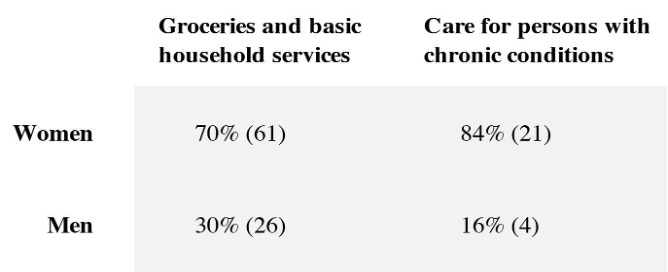

When put together with the overwhelming responsibility that women have for provisioning and care, our study shows that middle women (47–66 years old) are particularly taxed (see Table 3). The preponderance of unpaid caregiving is by women. In terms of chronic care, 84% is undertaken by women and 16% by men in our sample. Additionally, women have a greater responsibility for provisioning of groceries and other essential household services: 70% by women and 30% by men in our sample.

Table 3. Care and Household Provisioning Responsibilities by Gender

In terms of our organizational survey findings, the greatest concentration of federal funds was in the largest organizations of 100+ users served per month (88%). Sixty-six percent of the organizations in the sample that received federal funds as the main source of income for their organization were serving 500+ users per month. In terms of the services that were provided by the institutions in our sample, most provided physical and mental health services as well as pharmaceutical services. Our survey found that, among our respondents, women and men were employed and in leadership positions at near equal numbers.

Our onsite interviews and site surveys revealed that there are continuing infrastructure access issues in public roads and inhabited homes from Hurricanes Maria and Irma, the earthquakes, and compounding new limitations on access from the COVID-19 pandemic. The onsite interviews reveal a deep economic crisis that drives particularly poor residents to have little hope in government services and supports and leaves them disconnected due to lack of reliable transportation options. They instead are aided by and find hope in NGOs, charities, and each other. Homes we visited showed marked overcrowding, lack of resources for reconstruction, the hoarding of both pets and household items, and tenuous access to utilities. Our site surveys showed severe damage to schools which are currently underserving children according to our interviewees and are used as refuge sites during hurricanes. In addition, we noted that the government center in Guanica, which holds official records and provides core health and reconstruction services, is still closed.

Conclusions

Implications for Public Health Practice

Our preliminary analysis of the interviews has found that public spaces such as hospitals, schools, offices, fields, churches, and marketplaces comprise a dynamic context where vulnerability and safety are exchanged through systematic response. During disasters such as the hurricanes and earthquakes, public spaces like fields, sports centers, or schools were used as official and unofficial shelters, and became ecosystems where new social environments were crafted, however temporary. During the COVID-19 pandemic however, personal homes became resituated as sites of refuge. Disaster events changed the use of personal homes, as well as their symbolic and material production. Public health policy needs to consider, with gender-responsive planning, the spatiality of where people seek shelter or are compelled to remain. In thinking through healthcare system policy reform, attention to spatiality will factor in access to health care, mobility, resource management, telecommunications, and demographic changes.

Our household/individual survey showed that there was a significant concentration of household units with people with disabilities at the lowest income levels. Data from our in-depth interviews clarified that the impact on people with disabilities on the household is a constant demand on human and financial resources. Most importantly, when disasters require relocation, moving those with disabilities is a near insurmountable challenge for some households. The limitations on mobility and resources for households with disabilities needs to be considered when devising pre- and post-disaster healthcare policy.

Our interviews meanwhile identified several challenges to health care access that are present before, after, and during catastrophic natural events. These include limited access to specialized and primary care; lengthy travel time to the San Juan metropolitan area to attend appointments; relocation to the San Juan metropolitan region or outside Puerto Rico; the uneven application of basic health and safety protocols in medical institutions; absence of a continuously functioning communications infrastructure that enables a continuity in preventive care or emergency care; and a pervasive absence of mental health supports that impacts patients, health care personnel, and first responders.

Our organizational representative survey found that federal funds are highly concentrated in the largest of health care providing organizations, located in urban centers. Importantly, our preliminary interview data shows that access to health care immediately following a disaster event was most easily and regularly sought and found from small organizations with strong emotive and geographically proximal ties to the community. As a result, we would suggest that federal funds consider initiatives that provide emergency assistance to the organizations that are most trusted in the moment of crisis by southwestern Puerto Rican communities.

Site surveys showed differential impacts on health and government service access in the southwest of Puerto Rico. Guayanilla, for instance, does not have a working hospital with specialty services and is currently served instead by mobile clinics. Additionally, we noted in Ponce a closure of specialty clinics due to earthquake damaged buildings. Meanwhile, Adjuntas town center has been redesigned to be more resilient as a fully solar-powered central business district. While our individual survey showed that the average driving distances to primary care are between 30 minutes to one hour, there is no reliable public transportation and access to vehicles is restricted for those living in poverty. When no reliable public transportation is present, the actual access travel time to primary care and specialists ranges from 2–6 hours.

In general terms, the narratives highlighted recurrent communication problems between health institutions, including hospitals, clinics, and Puerto Rico and municipal Health Departments; insurance coverage gaps; and an absence of sufficient caregivers in several areas but most notably among specialized medical personnel such as physicians, nurses, and therapists. The gaps in medical specialists reduce access to preventative and emergency care according to our interviewees. When asked about solutions, many interviewees mentioned the importance and current lack of training and retention programs for first responder and health providers of all types. Our preliminary interview data shows that out-migration due to the personal impact of disaster relief on health care providers and improved household economic opportunities in the U.S. mainland has reduced the availability of qualified first responders, health care support workers, and medical professionals. The lack of trained personnel taxes households and communities most particularly during disaster events. According to our interview data, the absence of caregivers, doctors, and health personnel during natural catastrophic events and the pandemic increases the wait times for appointments and the appointment time once a medical service is offered.

Dissemination

We are using the Facebook group page that we created for recruiting to maintain public outreach concerning the study and to disseminate the project findings. The web page includes a brief background about the research, including key concepts, and short bios for the Principal Investigators. As components of the project are completed, while keeping respondent identities confidential, we are sharing our preliminary findings such as through tables displaying our survey results. We are doing this to share what we learn and encourage a participatory discussion. Once the entire project is complete and all data are analyzed, the completed report will be disseminated through this website, to our respective institutional systems, and to the Puerto Rican health providers with whom we are in contact.

Limitations

In the original proposal we allowed for the possibility that we might be able to do in-person fieldwork during at least part of the study period since we anticipated the COVID-19 pandemic would have diminished in threat by late spring 2021. However, it in fact worsened within Puerto Rico as we were underway with our qualitative component. Out of our need to follow safety protocols to protect respondents as well as the study team, we had to restructure our work. Indeed, some community leaders asked us not to visit physically during the first months of our project. This resulted in a dependence on primarily remotely conducted interviews, which have inherent limitations. For instance, we were only able to access individuals from the private spaces where they could communicate with us without external noise, so we were unable to get a sense of the broader social and cultural context within which they function. This was a heavy loss for us as ethnographers. In addition, intermittent gaps in internet access have impacted our work. Most importantly, internet access is not consistent in the area we studied in large part because of infrastructure gaps, geographic constraints, and the financial cost so that those who are most vulnerable and marginalized in southwestern Puerto Rico are those with whom we have yet to be able to conduct interviews. While phone conversations or WhatsApp interview opportunities were offered, interviewees were not inclined to accept interview invitations that did not allow them to see the researchers (if only via video).

In addition, the qualitative and quantitative data sets we collected and are drawing from in our findings are not representative samples and this impacts the scalability of our findings. We believe that, nevertheless, our preliminary findings thus far raise important new questions as well as insights.

References

-

Pescaroli, G. & Alexander, D. (2015). A definition of cascading disasters and cascading effects: Going beyond the “toppling dominos” metaphor. Global Risk Forum Davos Planet@Risk, 3(1), 58–67. ↩

-

Cordero-Guzman, H., Calderon, J., & Davila, J. (2015). Puerto Rico’s Economic Crisis: Overview and Recommendations for Action. Hispanic Federation. https://hispanicfederation.org/images/pdf/hfprpolicy2015.pdf ↩

-

De Dios Santos, J. (2020, January 22). Interpreting the 2020 Puerto Rico earthquakes with data. Medium. https://towardsdatascience.com/interpreting-the-2020-puerto-rico-earthquakes-with-data-e241cdb2a14e ↩

-

U.S. Geological Survey. (2020, May 26). USGS Scientists find seafloor faults near Puerto Rico quakes’ epicenters. USGS News. U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.usgs.gov/news/usgs-scientists-find-seafloor-faults-near-puerto-rico-quakes-epicenters ↩

-

Bárcena, A. (2021). The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: An opportunity for a systemic approach to disaster risk for the Caribbean/ Forward by the Executive Secretary of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). COVID-19 Report. ECLAC-UNDRR. https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/publication/files/46732/S2000944_en.pdf ↩

-

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). (2020, April). The COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating the care crisis in Latin America and the Caribbean. COVID-19 Report. CEPAL/ECLAC. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/45352/1/S2000260_en.pdf ↩

-

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). (2021, February). The economic autonomy of women in a sustainable recovery with equality. COVID-19 Special Report No. 9. CEPAL/ECLAC. https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/publication/files/46634/S2000739_en.pdf ↩

-

Niles, S. & Contrera, S. (2019). Social vulnerability and the role of Puerto Rico’s healthcare workers after Hurricane Maria. Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Grant Report Series, 288. Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. Available at: https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/social-vulnerability-and-the-role-of-puerto-ricos-healthcare-workers-after-hurricane-maria ↩

-

Roman, J. (2015). The Puerto Rico Healthcare Crisis. Annals of American Thoracic Science, 12(12): 1760–1763. PMID: 26551268. Doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201508-531PS. ↩

-

Perreira, K., Peters, R. Llalemand, N. & Zuckerman, S. (2017). Puerto Rico Health Care Infrastructure Assessment: Site Visit Report. Urban Institute Research Report. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/87011/2001050-puerto-rico-health-care-infratructure-assessment-site-visit-report_1.pdf ↩

-

World Health Organization. (2010). Key Components of a Well-Functioning Health System. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/EN_HSSkeycomponents.pdf?ua=1 ↩

-

Benavides, X. (2020). Disparate health care in Puerto Rico: A battle beyond statehood, University of Pennsylvania Journal of Law and Social Change, 23(3): 164–202. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/jlasc/vol23/iss3/1 ↩

-

Mach, A.L. (2016). Puerto Rico and Health Care Finance: Frequently Asked Questions, U.S. Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report 7-5700. CRS. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44275.pdf ↩

-

García-López, G. A. (2018). The multiple layers of environmental injustice in contexts of (un)natural disasters: The case of Puerto Rico post-Hurricane Maria. Environmental Justice, 11(3), 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2017.0045 ↩

-

Tormos-Aponte, F. (2018, April 2). The politics of survival. Jacobin Magazine. https://jacobinmag.com/2018/04/puerto-rico-left-hurricane-maria-colonialism-independence ↩

-

García López, G. A. (2020). Reflections on disaster colonialism: Response to Yarimar Bonilla’s “The wait of disaster.” Political Geography, 78, 102170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102170 ↩

-

Lloréns, H., & Stanchich, M. (2019). Water is life, but the colony is a necropolis: Environmental terrains of struggle in Puerto Rico. Cultural Dynamics, 31(1–2), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0921374019826200 ↩

-

Bradshaw, S. (2013). Gender, Development, and Disasters. Routledge. ↩

-

Bradshaw, S. (2014). Engendering development and disasters. Disasters, 39(s1), s54–s75. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12111 ↩

-

Enarson, E., Fothergill, A., & Peek, L. (2018). Gender and disaster: foundations and new directions for research and practice. In Handbook of Disaster Research, edited by Rodríguez, H., Donner, W., and Trainor, J.E. Springer, 205–223. ↩

-

Erman, A., De Vries Robbe, S. A., Thies, S. F., Kabir, K., & Mauro, M. (2021). Gender Dimensions of Disaster Risk and Resilience: Existing Evidence. The World Bank and the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR). https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35202 ↩

-

Henrici, J. (2010). A Gendered response to disaster: The Aftermath of Haiti’s earthquake. Anthropology News 51(7), 5. ↩

-

Henrici, J., with Shaw, E. & Childers, C. (2015). Get to the bricks: the experiences of black women from New Orleans public housing after Hurricane Katrina. IWPR. ↩

-

Henrici, J. & Helmuth, A. S. (2010). Women in New Orleans: Race, poverty, and Hurricane Katrina. IWPR. ↩

-

Henrici, J., Helmuth, A.S., & Carlberg, A. (2012). Doubly displaced: Women, public housing, and spatial analysis after Katrina, in The Women of Katrina: How gender, race, and class matter in an American Disaster, edited by David, E. and Enarson, E. Vanderbilt, 142–154. ↩

-

Neumayer, E., & Plümper, T. (2007). The gendered nature of natural disasters: The impact of catastrophic events on the gender gap in life expectancy, 1981–2002. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 97(3), 551–566. ↩

-

Yadav, P. & Kelman, I. (2019). Examining cascading disasters and cascading effects through a gender lens. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, 41. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2019AGUFMNH41C0934Y ↩

-

Crenshaw, K.W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1(8): 139–167. ↩

-

Crenshaw, K.W. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review 43(6):1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039 ↩

-

Carastathis, A. (2016). Intersectionality: Origins, Contestations, Horizons. University of Nebraska. ↩

-

Collins, P.H. (2011). Piecing together a genealogical puzzle: Intersectionality and American pragmatism. European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy. 3(2): 88–112. https://doi.org/10.4000/ejpap.823 ↩

-

Lloro-Bidart, T. & Finewood, M. H. (2018). “Intersectional feminism for the environmental studies and sciences: looking inward and outward.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 8 (2): 142–151. 10.1007/s13412-018-0468-7. ↩

-

Gaillard, J. C. (2010). Vulnerability, capacity and resilience: Perspectives for climate and development policy. Journal of International Development, 22(2), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1675 ↩

-

Gaillard, J. C. (2019). Disaster studies inside out. Disasters, 43(S1), S7–S17. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12323 ↩

-

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., Davis, I. (2004). At Risk. Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters, second ed., Routledge. ↩

-

Tierney, K. (2014). The Social Roots of Risk: Producing Disasters, Promoting Resilience. Stanford. ↩

-

Caraballo-Cueto, J., & Godreau, I.P. (2021). Colorism and Health Disparities in Home Countries: The Case of Puerto Rico. J Immigrant Minority Health (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01222-7 ↩

-

Gaillard, J.C., Cadag, J.R.D. & Rampengan, M.M.F. (2019). People’s capacities in facing hazards and disasters: an overview. Natural Hazards 95, 863–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3519-1 ↩

-

Louis-Charles, H. M., Howard, R., Remy, L., Nibbs, F., & Turner, G. (2020). Ethical considerations for postdisaster fieldwork and data collection in the Caribbean. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(8), 1129–1144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220938113 ↩

-

Pastor, M., Bullard, R., Boyce, J.K., Fothergill, A., Morello-Frosch, R. & Wright, B. (2006). Environment, Disaster, and Race After Katrina. Race, Poverty & the Environment 13(1): 21–26. ↩

-

Palinkas, L.A. (2020). Hurricane Maria and Puerto Rico. In Global Climate Change, Population Displacement, and Public Health, 35–52. Springer. ↩

-

Gamboa, S. (2021, April 26). Puerto Rico’s population fell 11.8% to 3.3 million, census shows. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-ricos-population-fell-118-33-million-census-shows-rcna767 ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020, last revised April). About the Puerto Rico Community Survey. The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/about/puerto-rico-community-survey.html ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019a). Population 60 years and over in Puerto Rico. [Table.] Retrieved May 15, 2021, from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=ACSST1Y2019.S0102PR&tid=ACSST1Y2019.S0102PR&hidePreview=true ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019b). U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Puerto Rico. [Table.] Retrieved May 14, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/PR ↩

-

Downer, B., Crowe, M., & Markides, K. (2018). Population aging and health in Puerto Rico. In Contextualizing Health and Aging in the Americas: Effects of Space, Time and Place,7–17. Springer International Publishing https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00584-9_1 ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. (2018.) A Snapshot of Disability in Puerto Rico. Fact Sheet. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/impacts/puerto-rico.html ↩

-

Yang-Tan Institute on Employment and Disability, Cornell University. (2016). 2016 Disability Status Report Puerto Rico. Cornell. https://www.disabilitystatistics.org/StatusReports/2016-PDF/2016-StatusReport_PR.pdf ↩

-

Keith-Jennings, B. (2020). Introduction to Puerto Rico’s Nutrition Assistance Program. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/introduction-to-puerto-ricos-nutrition-assistance-program ↩

-

Gobierno de Puerto Rico/Government of Puerto Rico. (n.d.). Portal de datos geográficos gubernamentales. http://gis.otg.gobierno.pr/Geografia_PR.htm ↩

-

U.S. Geological Survey. (n.d.) Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands: Index to topographic and other map coverage. https://store.usgs.gov/assets/MOD/StoreFiles/zoom/PDF/PR-VI.pdf ↩

Sanabria-León, W., Henrici, J., Torres, M., Cardona, A., Fairbairn, A., & Eaton, E. (2021). Cascading Disasters, Gender, and Vulnerability in Southwestern Puerto Rico (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 13). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder.