Port of Antwerp © August Brill 2013

FOR MORE THAN A DECADE, the threat of terrorism from weapons of mass destruction (WMS) has been on the forefront of the international security agenda. In an increasingly globalized society, it is of utmost priority to detect and interdict illicit trafficking of radioactive and nuclear materials (RN) in order to prevent individuals and organizations—those who are willing to perpetrate acts of WMD terrorism—from acquiring such materials. Recently revealed terrorists’ surveillance of a nuclear official in Belgium only confirms this importance. In this context it is also worth noting that “traditional” transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) are increasingly collaborating with terrorist organizations to traffic commodities, such as arms, narcotics, antiquities, humans, as well as wildlife and wildlife body parts. Another emerging trend is the hybridization of terrorist organizations that are engaging in criminal activities such as illicit trafficking of narcotics to fund their terrorist activities (Picarelli 2006, Picarelli 2012a, Picarelli 2012b, Picarelli and Shelley 2007, Sanderson 2004).

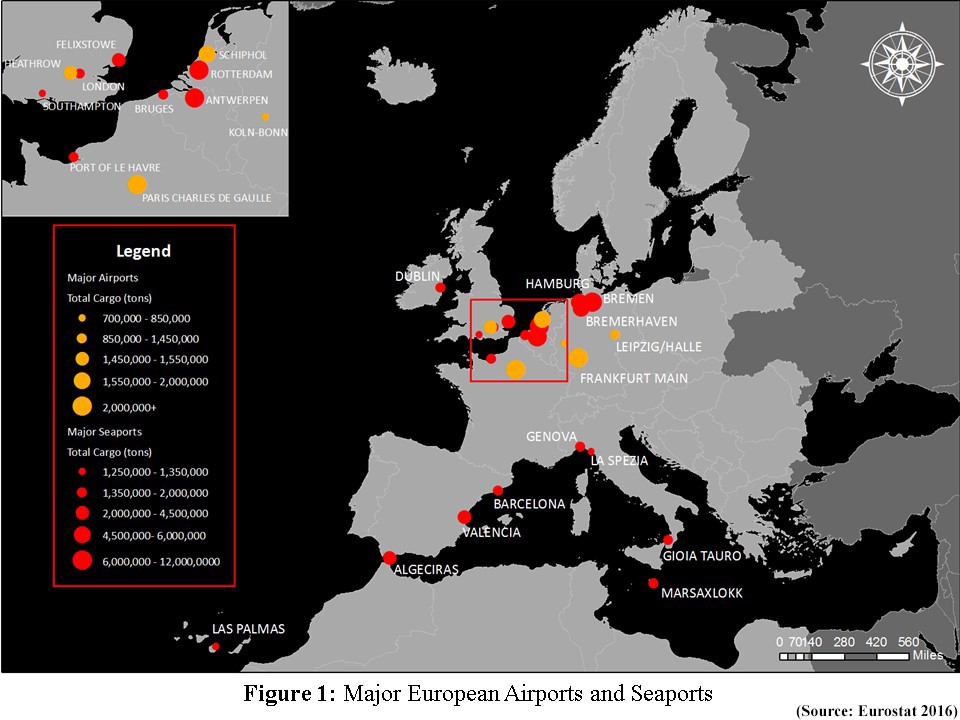

In response to the potential threat of WMD terrorism, the international community has launched various political and legal initiatives to prevent illicit trafficking of RN materials via maritime means. Indeed, more than 58 million 20-foot equivalent units of containers are shipped around the world annually via 490 maritime trade routes, and international deep-sea container ports are still being used by TCOs and terrorist organizations alike to transship and transload illicit goods. These alarming statistics make commercial maritime shipping industry uniquely vulnerable to exploitation by nefarious actors seeking to traffic RN materials.

Through a case study of the Port of Antwerp, Belgium, we examine ways the international maritime security initiatives (i.e. Proliferation Security Initiative, Megaports Initiative, etc.) are implemented at one of the largest and fastest growing deep-sea container ports in Europe with services to and from the Americas, Africa, the Middle East, and the Indian subcontinent. We also seek to identify strengths and potential weaknesses of the current legal and political framework designed to curb illicit RN materials-trafficking. Additionally, we try to determine whether the existing initiatives are implemented with efficiency and respected by those connected to the maritime industry, or if the reality is far from ideal.

Port of Antwerp © August Brill 2013

Case selection and methodology

Three major characteristics led us to select the Port of Antwerp as the subject of our case study, beyond the fact that it is one of the largest and fastest growing deep-sea container ports in Europe. First, geospatial analyses have identified the Port of Antwerp as the potential European maritime chokepoint where multiple licit and illicit pathways converge (Boyd and Sin 2014, Sin and Boyd 2016). Second, the Port of Antwerp represents an excellent example of the latest security measures implemented at a large European international maritime cargo handling facility. Finally, the port reflects the convergence of national Belgian, European Union and international policies, which provide a unique opportunity to observe the operation of multiple types of security policies in a single location. Although we chose to conduct our case study at the Port of Antwerp, it is worth noting that there is no intentional illicit RN material trafficking case reported at the Port of Antwerp. Several key officials involved in the operations and security of the Port of Antwerp were interviewed to provide insights to our case study. We also researched all available open- source media and academic literature pertaining to the Port of Antwerp’s operations and security measures, as well as reports produced by governmental and non-governmental organizations. Additionally, we conducted an analysis of all relevant international and European security regimes, legislations, and regulations that Belgium (and therefore the Port of Antwerp) is obligated and/or has agreed to follow.

Background: physical and jurisdictional complexity

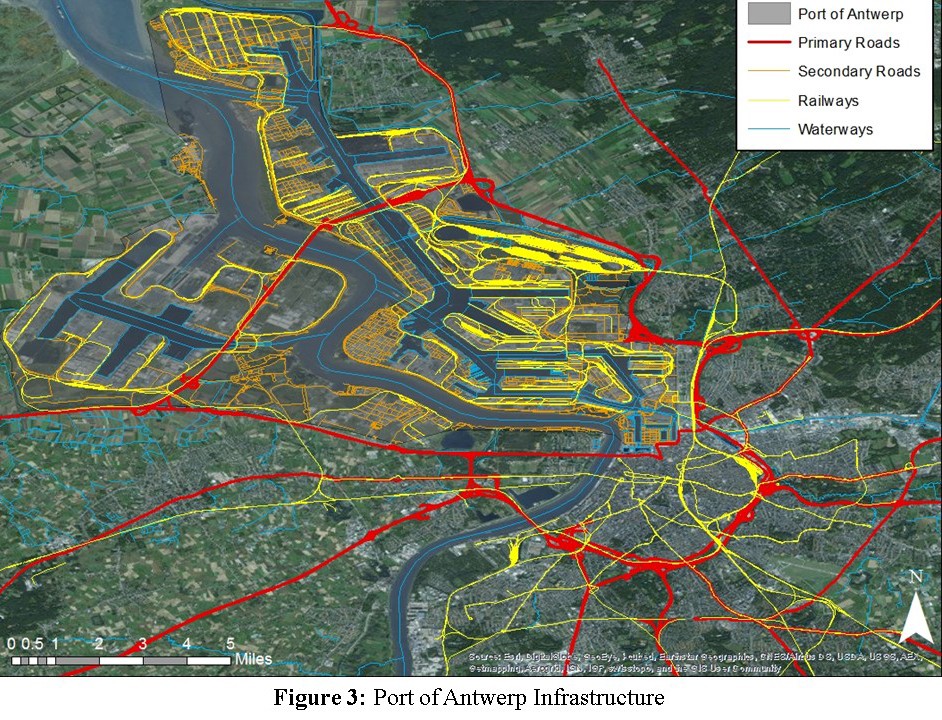

The Port of Antwerp is the largest container port in Belgium and the second busiest container port in Europe (Port of Hamburg 2016). The port accounted for roughly 80 percent of all containers shipped to the United States and Canada from Europe in 2014 (Port of Antwerp 2014a). Its proximity to European consumer markets (located roughly 80 kilometers (129 miles) inland from the North Sea on the River Scheldt) gives it a competitive advantage over other European ports (World Port Source 2016).

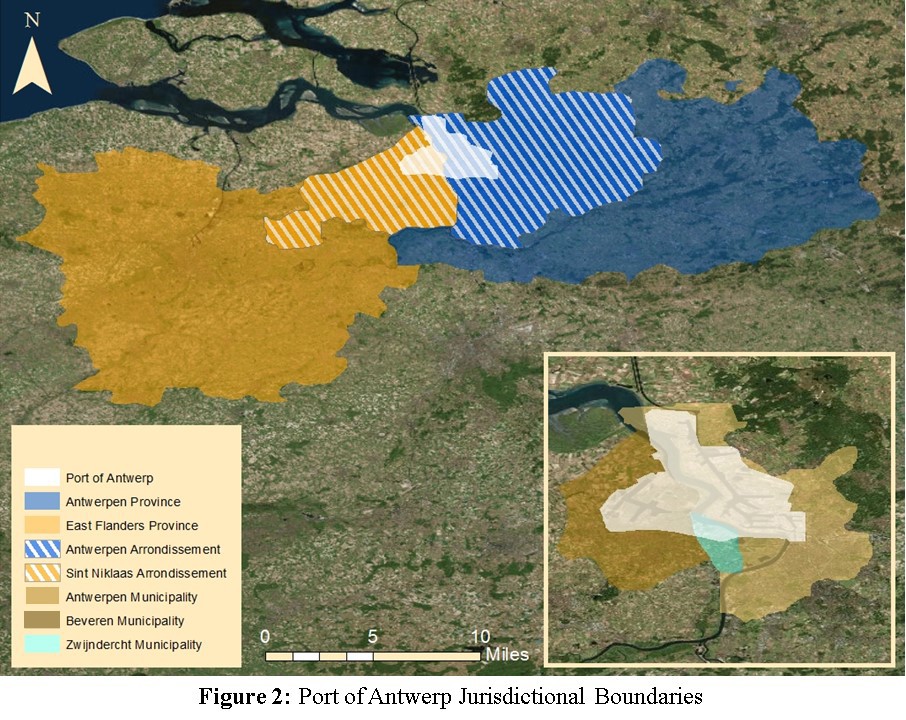

Although the Port of Antwerp may appear to be a singular entity falling under one jurisdictional authority, in reality, several jurisdictional lines are present within the area. The port is located in two Belgian provinces (Antwerp and East Flanders), three municipalities (Antwerp, Beveren, and Zwijndrecht), and two judicial districts (Antwerp and Dendermonde). It also straddles multiple administrative and judicial boundaries. Within the Port of Antwerp area, nine government agencies1 have a role in some aspect of the port security. There are also eight law enforcement agencies—three local2 and five federal3– operational at the Port of Antwerp. Additionally, there are two prosecutor’s offices (Antwerp and Dendermonde) that lay claims to the jurisdiction over the port; the Belgian intelligence and security services, and the Federal Agency for Nuclear Control also play a large role in port security. Other agencies in the port’s security team include the Customs, the Environmental Inspection, and various local fire departments. (DeBoeck, et al. 2014) While all of these stakeholders are responsible for certain aspects of the port security, they all have divergent operational requirements and priorities; therefore, developing and implementing a comprehensive port security policies and procedures that can have each stakeholder’s buy-in and leverage the unique capabilities each stakeholder possesses is a monumentally challenging task.

International initiatives, regulations, and resolutions signed by Belgium

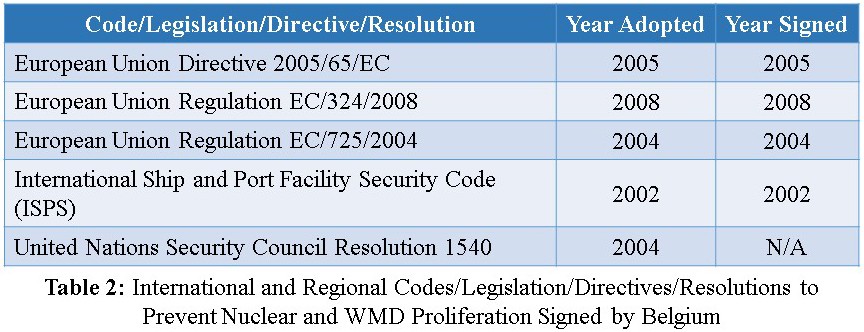

Recognizing the threat of WMD terrorism and its implications, Belgium participates in various international and regional initiatives, codes, regulations and directives4 in order to prevent WMD terrorist incidents and to curb illicit trafficking of RN materials.

Belgium also has joined a number of international initiatives focused on preventing nuclear and WMD proliferation and terrorism (see Tables 1 and 2). As the largest deep-sea container port in Belgium, the Port of Antwerp is subject to all of the conditions and terms of the international and regional initiatives, legislations, codes, directives, and resolutions that Belgium must adhere to. Tables 1 and 2 (below) provide a list of agreements related to preventing nuclear and WMD proliferation and to terrorism that Belgium has signed:

Current security measures, procedures, and protocols

The Port of Antwerp unites multiple security actors at several levels due to the multi-faceted nature of the concept ‘security’ and the administrative and judicial complexity of the port area.5 There are more than 20 governmental bodies, justice and policing bodies, and inspection and rescue actors (DeBoeck, et al. 2014). Although no single security actor or agency specifically focuses on the detection of illicit trafficking of RN materials, this issue falls within the broad scope of four key operational agencies charged with the daily operational mission of securing the port: Customs and Excises, the Harbor Master’s Office, the Federal Agency for Nuclear Control (FANC), and the Federal Maritime Police.

The primary RN materials inspection tool for container traffic in the port is the Megaports portal monitors. In 2004 Belgium joined the Megaports Initiative and has contributed approximately $17 million to the initiative between its two ports, Antwerp and Zeebrugge (NNSA 2013). As a port participating in the Megaports Initiative, all of its major terminals are equipped with Megaports Initiative scanners, and the majority of the containers processed at the port go through these scanners. The port is also equipped with secondary fixed scanners and tertiary mobile scanners that can be used to conduct a more detailed inspection of containers. (Pellens, et al. 2010)

In 2012 the Port of Antwerp developed a new security protocol, which was implemented and exercised under the observation of the European Commission representatives. The “Exercitium, Drill and Exercise Handbook,” drafted by the Port Authority after the completion of the exercise at the request of the European Commission, has been adopted throughout the European Union as a model (Port of Antwerp 2012). In 2013 the Port Authority introduced a game called “Serious Game,” which port users and the public can download and play on their computers or mobile devices to learn how to contribute to the safety and security of the port (Port of Antwerp 2013a).

Port of Antwerp © August Brill 2013

In an effort to allow for earlier intervention of police in the investigation of suspicious or possible criminal/terrorist activities at and around the port area, the Port Authority established a Local Information Network (LIN) at the end of 2013. The network brings private companies, various port agencies, and local authorities together in an information- sharing environment. The LIN not only allows the private companies and the port agencies to report suspicious activities to the local authorities, but it also allows the local authorities to share information with the companies and port agencies about possible threats at and around the port area. As of February 2014, the mayors of Antwerp, Beveren, and Zwijndrecht, as well as the Antwerp port alderman, the Belgian Federal Policy, the Shipping Police, senior police officers of the local jurisdictions, and the Port Authority had all signed the LIN protocol.

Since the development of LIN, the Port Authority has approached 650 companies to join the network, and currently more than 450 companies participate in the LIN protocol. (Port of Antwerp 2014b, 2013b)

To counter the constantly increasing cyber threat faced by the Port, and as a response to the hacking incident6 that was uncovered in 2013, the Port Authority, in concert with the Antwerp Port Community System (APCS) and the Belgian Federal Cyber Emergency Response Team (CERT), set up a special cyber security taskforce at the end of 2013 (Port of Antwerp 2013b). Moreover, the port implemented additional container-security measures. One of the new measures includes the Container Release System–originally developed by MSC–in which the users have to log onto a secure portal that is hosted on an independent network from the Port’s network in order to gain access to the container release data (Port of Antwerp 2013c). Other security measures at the container terminals include integrated electronic data management (EDI), International Ship and Port Security (ISPS) certification, and the Secured Alfpass card management system (Port of Antwerp 2016d).

Security challenges and potential issues

Although more than 90 percent of the containers processed at the port go through the Megaports Initiative scanners when entering and leaving the port, a number of the containers still do not get scanned. There are two primary reasons for this: 1) those containers that are directly transloaded from one ship to another (both international and domestic shipping transfers) do not have to be scanned, and they can then be offloaded at another port that is not a part of the Megaports Initiative; and 2) of all the containers that do go through the portal RN detector, a very small percentage of them are selected for secondary and tertiary scans due to the extremely high volume of the containers flowing through the port.

Additionally, primarily because of this high volume of containers, when a container is selected for further scanning it takes a long time for the transporter to submit the container to further scanning. As a result, the material of interest could be dumped or transferred to other means of transportation prior to the container being submitted for scanning (Fanielle and Volders 2014).

Port of Antwerp © August Brill 2013

The primary function of the customs office, the agency that receives the monitor alarm information from the Megaports portal scanners, is to detect and curb illicit trafficking of goods (i.e. narcotics and counterfeit goods) and not necessarily to look for RN materials. Likewise, the Federal Maritime Police’s main task is to actively control the port area to prevent and investigate “conventional” crimes. In cases when alarms are deemed credible7 the Federal Agency for Nuclear Control (FANC)’s Security & Transport Department will be notified for assistance. Although this department is the central point of contact for the port authorities in an event of credible RN alarm, its mission is to protect the people in the potentially affected area from radiation and/or contamination, in accordance with the IAEA’s guidance document. Again, like the customs office and the maritime police, though FANC must respond to a potential RN event, its focus is not in preventing illicit trafficking of RN materials. Finally, although the Harbor Master Office’s Port Security & Safety Department is responsible for monitoring all port terminal operators’ and port tenant companies’ correct implementation of the ISPS-guidelines, the department is still not charged with proactively monitoring attempts of illicit RN materials trafficking (Fanielle and Volders 2014).

The Maritime Security Law (2007) and the Royal Decree on Maritime Security (2007), pursuant to the EU Regulation EC/725/2004 and the EU Directive 2005/65/EC, establish two overarching bodies responsible for proactively securing the port and creating preventive measures against terrorist threats. These are the National Authority for Maritime Security, and the Local Committee for Maritime Security (in the Port of Antwerp’s case, the Port of Antwerp Local Committee for Maritime Security). Although these two organizations are designed to integrate intelligence and interdiction capabilities to prevent terrorism, there is no clear guidance on which agency is in charge of orchestrating the operations on the ground.

Another challenging issue is that the Port of Antwerp is considered an open port, meaning most of the port area is not controlled or has very limited control. In fact, there are some parts of the port in which private residences are situated. Although the immediate terminal areas and other sensitive areas are secured and controlled, the openness of the port does present a significant security challenge—not only for preventing illicit trafficking, but also because the port’s facilities and infrastructure could be the physical target of a terrorist attack. It is also worth noting that all commercial ports have an economic finality, meaning that economic interests of the ports will almost always supersede all other concerns, including security. Security of the ports, at the most fundamental level, is vital only because it ensures the economic viability and the interests of the ports as well as those private entities operating within and around them (Fanielle and Volders 2014).

Port of Antwerp © August Brill 2013

Finally, the port faces two emerging security challenges: cyber security, including the potential danger a cyberattack could pose on the port’s security; and insider threat, whereby someone affiliated with the port could be corrupted or recruited to facilitate illicit trafficking. According to several Belgian federal and local officials working at the port, cyberspace could be the weakest link in the port’s security posture.

Cyberspace, together with a corrupted or recruited insider, could represent the best chance of success for any potential adversary attempting to illicitly traffic RN material through the port (Fanielle and Volders 2014).

Conclusion

Through our examination of the security measures and procedures at the Port of Antwerp, we were able to gain valuable insights into the strengths and potential weaknesses of the current international maritime security initiatives intended to curb illicit RN material trafficking.

The current international and regional maritime security initiatives appear to provide for an appropriate level of security requirements and recommended implementation measures to curtail illicit trafficking of RN materials via maritime means. Critical pressure points common to all initiatives were found to be a) active engagement of officials and private partners; b) specific mandate; and c) sustainability. Irrespective of the initiatives’ design, if one of the previously identified criteria is not met, the collective power of the initiatives’ measures will not be as strong.

The authorities and private partners at the Port of Antwerp were very enthusiastic about implementing security measures to address the threat of WMD terrorism and illicit trafficking of RN materials. To that end, the Port of Antwerp has implemented various security measures, procedures, and protocols as required and recommended by the international and regional initiatives, regulations, and resolutions to which Belgium is party. For example, the Port of Antwerp has a well implemented ISPS certification program and Megaports Initiative scanning procedures. The authorities and civilian partners of the port are also actively engaged in countering the cyber security threat posed by individual hackers and organized criminal groups. Additionally, the Port Authority is constantly raising the awareness of the operators and tenant companies about the security measures as well as the potential threats.

Despite all of its successes, the large physical size, extremely voluminous commercial throughput, and jurisdictional complexities of the port pose unique challenges to the authorities who are charged with implementing the security measures and procedures to mitigate vulnerabilities and secure the port’s facilities and infrastructure. One of the most unique challenges stems from the jurisdictional complexities of the port. A variety of measures and procedures have been implemented at the Port of Antwerp in response to the threat of WMD terrorism and illicit trafficking of RN materials. Still, no one agency at the port has a specific mandate to focus on or is designated as the lead agency to monitor and coordinate the responses to a potential illicit RN materials trafficking or WMD terrorism incidents. While it seems the Port of Antwerp Port Authority is responsible for coordinating all of the relevant agencies’ response to any terrorist activities in and around the port once an incident occurs, it is still unclear which agency has the specific mandate to monitor and respond to illicit RN materials trafficking.

Balancing the scale between security and operational efficiency is one of the most difficult tasks that managers of facilities, companies, and organizations face. The Port of Antwerp is no different. The managers and security officials toil with these difficult decisions every day. The security of the port infrastructure and facilities is important. And stopping illicit trafficking of RN materials is paramount. But the security measures and procedures cannot degrade the operational efficiency of the port to the point where it becomes economically unsustainable. This harsh reality of the seemingly inversely correlated relationship between security and operational efficiency not only presents a challenge for the authorities as they attempt to find the “right” balance, but it also presents openings that can potentially be exploited by adversaries.

Balancing the scale between security and operational efficiency is one of the most difficult tasks that managers of facilities, companies, and organizations face

Constant communication and information-sharing among the different agencies, offices, and private partners operating in and round the port, as well as the continuous outreach programs designed to increase the awareness of all parties about the potential and consequences of illicit RN materials trafficking, are extremely valuable in mitigating potential weaknesses of the initiatives derived from jurisdictional complexity and economic sustainability. One can compare this to the direct correlation that DeCanio (1993) observed about the implementation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Energy Star program8 and the level of outreach activity conducted by EPA field offices located throughout the country. DeCanio found that the level of consumer and business awareness of the Energy Star program’s benefits and the level of participation in the program is directly correlated with the level of outreach activity conducted by the EPA field office responsible for overseeing that particular area/region. Similarly, developing and implementing effective security measures, policies, and procedures that are sustainable is only the first half of the equation in securing our ports against the threat of illicit RN material trafficking, or any other threat. The second half of the equation that must not be overlooked if we are to achieve a truly comprehensive security posture is the outreach and partnership programs that involve all stakeholders within and around the ports. The more active the port authorities are in reaching out to the public and private partners in and around the ports about the threats they face as well as the countermeasures already in place to counter those threats, the more aware the people will become and more buy-in there will be, which will lead to increased effectiveness of the security measures, policies, and procedures overall.

Acknowledgment

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Non-Conventional Threat (Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear) USA 2015 Conference. Although some additional research was conducted to verify and update the facts and figures for this revision, primary information collection, including the interviews, were all conducted between July and September of 2014.

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate’s Office of University Programs and Human Factors/Behavioral Sciences Division (HFD) through START. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations presented here are solely the authors’ and are not representative of DHS or the United States Government.

References

Boyd, Marcus A., and Steve S. Sin. 2014. Geospatial Information Systems Transnational Illicit Trafficking Route Analysis. Interim Report to U.S. Department of Homeland Security, College Park, MD: National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START).

Bureau of Transportation Statistics. 2013. North American Transborder Freight Data: Main Search Page. Accessed August 26, 2014. https://transborder.bts.gov/programs/international/transborder/TBDR_QA.html.

De Boeck, Arne, Genserik Reniers, Marc Cools, Marleen Easton, and Evelien Van Den Herrewegen. 2014. "Optimizing Security Policies and Practices in the Port of Antwerp: Actors’ Perceptions and Recommendations." International Journal of Safety and Security Engineering 4 (1): 38-53.

EUROSTAT. 2016. Volume of Containers Transported to/from Main Ports - Quarterly Data (2015 - 2016). http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.dodataset=mar_go_qm_c2016&lang=en. (Accessed October 15, 2016)

Fanielle, Sylvain, and Brecht Volders. 2014. Interviews of Port of Antwerp Authorities (August - September).

National Nuclear Security Administration. 2013. Megaports Initiative. http://nnsa.energy.gov/aboutus/ourprograms/nonproliferation/programoffices/internati onalmaterialprotectionandcooperation/-5. (Accessed September 2, 2014)

Pellens, V., T. Clerckx, L. Hulshagen, W. Schroeyers, P. Fias, T. Peeters, F. Biermans, and S. Schreurs. 2010. "Transport of NORM in the port of Antwerp: from megaports to a special purpose measurement methodology." Sixth International Symposium on Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material. March 22-26, Marrakesh, Morocco: IAEA Proceedings Series, STI/PUB/1497.

Picarelli, John. 2006. "The Turbulent Nexus of Transnational Organised Crime and Terrorism: A Theory of Malevolent International Relations." Global Crime 7 (1): 1-24.

Picarelli, John. 2012a. A Brief Discussion of the Nature and Convergence of Transnational Organized Crime and Terrorism (Vol. NCJ 238793). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice.

Picarelli, John. 2012b. "Osama bin Corleone? Vito the Jackal? Framing Threat Convergence through an Examination of Transnatinal Organized Crime and International Terrorism." Terrorism and Political Violence 24 (2): 180-198.

Picarelli, John, and Louise Shelley. 2007. "Organized Crime and Terrorism." In Terrorism Financing and State Responses: a Comparative Perspective, by Jeanne Geraldo and Harold Trinkunas, 39-55. Redwood City, CA: Standford University Press.

Port of Antwerp. 2012. Antwerp Port Security is a Model for Europe. http://www.portofantwerp.com/en/news/antwerp-port-security-model-europe. (Accessed September 1, 2014)

—. 2013a. Port Authority introduces Serious Game to boost port security. http://www.portofantwerp.com/en/news/port-authority-introduces-serious-game-boost-port-security. (Accessed August 31, 2014)

—. 2013b. Port of Antwerp Annual Report 2013. Antwerp, Belgium: Antwerp Port Authority. (Accessed August 31, 2014)

—. 2013c. Stepping Up the Fight Against Cyber-crime. http://www.portofantwerp.com/en/news/stepping-fight-against-cyber-crime. (Accessed September 2, 2014)

—. 2014a. Antwerp, Your Port of Choice: Containers. Antwerp, Belgium: Antwerp Port Authority, 3. (Accessed September 2, 2014)

—. 2014b. LIN, Collaboration for a Secure Port. http://www.portofantwerp.com/en/news/lin-collaboration-secure-port. Accessed (September 2, 2014)

—. 2016a. Port Organisation: Players in the Port. http://www.portofantwerp.com/en/players-in-the-port. (Accessed October 10, 2016)

—. 2016b. Port Organisation: The Port Area. http://www.portofantwerp.com/en/port-area. (Accessed October 11, 2016)

—. 2016c. Business: Liquid Bulk. http://www.portofantwerp.com/en/port-area. (Accessed October 9, 2016)

—. 2016d. Business: Terminal Operations. http://www.portofantwerp.com/en/terminal-operations. (Accessed October 9, 2016)

Port of Hamburg. 2016. Top 20 World Container Ports. https://www.hafen-hamburg.de/en/statistics/top-20-container-ports. (Accessed October 15, 2016)

Sanderson, Thomas. 2004. "Transnational Terror and Organized Crime: Blurring the Lines." SAIS Review 24 (1): 49-61.

Sin, Steve S., and Marcus A. Boyd. 2016. "Searching for the Nuclear Silk Road: Geospatial Analysis of Potential Illicit Radiological and Nuclear Material Trafficking Pathways." Chap. 9 in Nuclear Terrorism: Countering the Threat, edited by Brecht Volders and Tom Sauers, 159-181. New York: Routledge.

Stephen, DeCanio. 1993. "Barriers within firms to energy-efficient investments." Energy Policy 21 (9): 906-914.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2016. UNCTADstat. Accessed October 15, 2016. http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx.

World Port Source. 2016. Port of Antwerp: Port Commerce. http://www.worldportsource.com/ports/commerce/BEL_Port_of_Antwerp_25.php. (Accessed October 10, 2016)

-

The nine government agencies with responsibility for port security include the Belgian Ministry of Home Affairs; the Belgian Ministry of Justice, the Flemish regional government, the Governor’s Offices of the Provinces of Antwerp and East Flanders, the Mayor’s Offices of the City of Antwerp and the municipalities of Beveren and Zwijndrecht, and the Antwerp Port Authority. ↩

-

The local law enforcement agencies are Antwerp, Beveren, and Zwijndrecht. ↩

-

The federal law enforcement agencies are the Federal Judicial Police for Antwerp and Dendermonde; the Federal Administrative Police for Antwerp and Dendermonde; and the Federal Maritime Police. ↩

-

Belgium has joined and implemented the following international and regional initiatives, legal codes, and legislations that are most relevant the prevention of WMD proliferation through increased security measures, policies, and procedures at seaports: Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI); Megaports Initiative; Container Security Initiative (CSI); International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS); European Union (EU) Regulation EC/725/2004, “Enhancing Ship and Port Facility Security”; EU Directive 2006/65/EC, “Enhancing Port Security”, and EU Regulation EC/324/2008, “Procedures for Conducting Inspections in the Field of Maritime Security.” ↩

-

On one hand, security consists of port-related crimes such as illicit trafficking of goods, human smuggling, and scams with vehicles and waste. The port is a ‘logistical gateway’ to carry out other types of crime. On the other hand, security is related to the protection of the port itself from, primarily, a physical attack by terrorists. ↩

-

In June 2013, the Belgian authorities seized approximately a ton of heroin and cocaine after one of the shipping companies notified the Antwerp Port Authority that its container tracking system had been hacked. In October 2013, the Belgian authorities discovered the full extent of the security system breach at the port. The investigation found that narco-traffickers had hired hackers to break into the port’s computer systems as early as 2011 to facilitate the trafficking of narcotics through the port. According to the reports, the narco-traffickers hired hackers through the dark web. The narco-traffickers would hide their “commodities” in the banana and timber containers from South America. The hackers would facilitate the recovery of the “commodities” from the port by breaching into the port’s container location system and identifying the precise location of the relevant containers. The hackers will then change the pickup time and destinations of the containers, after which the narco-traffickers would send their own drivers to pick up the containers as “scheduled” with the “correct” documentation for pickup and delivery. ↩

-

It is worth noting that false alarms are common occurrences. Some products such as bananas, broccoli, and toilets often trips the monitor’s alarm because they give out a weak radioactivity signal. The Customs and Excises currently has the authority to arbitrarily decide whether or not to conduct a secondary and/or tertiary scanning of a particular container. ↩

-

Energy Star is a joint Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Department of Energy (DOE) program. The goal of the program is to protect the environment by encouraging consumers, businesses, and industry to adopt the use of energy efficient products and practices. The incentive to adopt such products and practices is that the adopters will see the return in the form of money saved on their energy costs. ↩

Steve Sin is currently a senior researcher at the Unconventional Weapons and Technology Division (UWT) of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), headquartered at the University of Maryland. Sin specializes in a broad range of international security, terrorism, and homeland security challenges. His expertise includes illicit trafficking of radiological and nuclear materials, cyber security, and emergency preparedness and management. His extensive experience includes a career as a U.S. Army officer, serving as a Military Intelligence Officer specializing in counterintelligence, counter-terrorism, and political-military affairs in Asia-Pacific. Sin is also a PhD candidate in political science (international relations and comparative politics) at the State University of New York at Albany.