Colorado’s Marshall Fire

Recovery, Mitigation, and Resilience Through a Social Equity Lens

Publication Date: 2025

Abstract

The Marshall Fire Recovery and Resilience Working Group collected perishable mixed methods data to understand how communities approach policies related to climate resilience in a post-disaster context as well as individual recovery trajectories after Colorado’s most destructive wildfire, which started on December 30, 2021. The Working Group administered the Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey to a panel of respondents at three different timepoints post-fire. The third wave of the survey was administered shortly after the two-year anniversary of the Marshall Fire, between February and April of 2024. The research team engaged fire-affected governmental and community groups to solicit feedback on the survey design and planned analyses of survey results. Results show that communities affected by the Marshall Fire have made significant progress in recovering from this disaster, with many respondents having rebuilt their homes and moved back. These successes are not universal, however. Two years after the fire, there are individuals and groups who continue to struggle and face specific challenges, such as older adults, those with lower insurance coverage, and those with lower household incomes. Moreover, our results showed that public land use policies to support hazard mitigation are more popular than individual-level hazard mitigation practices, such as residential energy efficiency codes. Interestingly, however, even in cases where stricter energy codes are not popular, many respondents reported adopting them voluntarily. These results may inform how local decision-makers strategize community engagement and resource allocation around hazard mitigation and rebuilding.

Introduction

On December 30, 2021, the climate-enabled and weather-driven Marshall Fire destroyed 1,084 homes and damaged many more in Louisville, Superior, and unincorporated Boulder County, Colorado, becoming the most destructive fire in the state’s history. For these communities and the growing number of places where climate change is increasing hazard risk, key questions have emerged: How are communities impacted by climate disasters in the short and long term? What factors influence individual and community decisions about how to rebuild and recover? How can communities increase resilience and make people safer in the face of an expanding set of threats?

The Marshall Fire Recovery and Resilience Working Group was formed in response to the disaster to help answer some of these questions. This report presents preliminary analysis of results from the third wave of the Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey, which was designed in collaboration with more than 30 national and international researchers, local government officials, and community groups in the affected areas. This novel, collaborative approach to survey design sought to balance community needs and concerns with those of the research community, and to track the recovery process and its impacts on residents as it unfolds over time. The survey was administered to residents of the fire-affected communities in three waves, occurring approximately around the 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year anniversaries of the fire.

Our examination of the Marshall Fire is a valuable case study of hazard mitigation policy in post-disaster contexts. Adopting hazard- and climate-resilient land use and building codes is a mitigation activity that was heavily discussed in public venues after the Marshall Fire (such as city council meetings), but these codes can have limited effects in already-developed communities. This is especially true in communities, like Louisville and Superior, which experienced extensive losses during the fire but had not historically been considered part of the wildland-urban interface and thus not built with wildfire hazard in mind. These communities are representative of the growing number of places that will be newly under threat as climate change worsens the frequency and severity of extreme weather events like wildfires (Liu et al., 20151). This study explored how disaster events, like the Marshall Fire, shape public support for, or against, climate resiliency policies in communities affected by climate change.

The Marshall Fire followed several other recent major disasters in Colorado that spurred significant county- and state-level institutional changes aimed at building more disaster-resilient communities (Colorado Resiliency Office, n.d.2). This study examined how residents and local leaders perceived and debated the benefits and costs of long-term mitigation policies in the Marshall Fire recovery context. Lastly, this study focused on equity in disaster recovery processes, particularly how factors like income, age, and housing tenure impact recovery trajectories for Marshall Fire survivors. Given the unprecedented property damage during the Marshall Fire, where over 1,000 homes were completely destroyed and hundreds more damaged, our equity analysis focused on the large cohort of people who were forced to navigate total home-loss and displacement from their homes (whether they were renters or owners). We translated our research findings on hazard mitigation, equity, and climate resilience into clear, digestible, and actionable lessons that we have shared publicly through our project website and public meetings, as well as focused dissemination to emergency managers, community groups, and government entities in the fire-affected areas.

Literature Review

In the wildfire context, multiple social groups have been shown to suffer disproportionate impacts and barriers to recovery, with potential implications for long-term mitigation and resilience-building. For example, wealthier households tend to have more comprehensive insurance coverage, and lower income households face more challenges in the process of rebuilding or finding new housing (Fothergill, 20043). In a context in which implementing mitigation measures is largely voluntary and involves additional costs, these documented inequities in recovery may translate into uneven adoption of mitigation and resilience-promoting actions.

The affected Boulder County communities are more affluent compared to the rest of the state ($92,000/year median income vs. $80,000/year statewide) and majority white non-Hispanic (77% vs. 67% statewide) (U.S. Census Bureau, 20224). These communities also lean to the liberal side of the political spectrum and have strong stated commitments to climate resilience and social equity. For example, Boulder County first adopted a climate resilience plan in 2012 ahead of most U.S. local governments (Boulder County, 20235). Louisville (City of Louisville, 20206) and Superior (Town of Superior, 20227) also have broad climate action plans that span sectors; Louisville has committed to being Zero Carbon by 2030. The Marshall Fire thus starkly illustrates that even “climate-forward” and relatively advantaged communities can be directly impacted by climate-driven disasters. Understanding how these communities respond, and the successes and challenges they encounter, can provide important insights for other communities.

Furthermore, even in areas that are relatively advantaged overall, disaster impacts are not felt equally by all members of society, and disasters often worsen pre-existing inequities such as access to resources and proximity to environmental hazards (Agyeman et al., 20038; Tierney, 20079). The extent to which these communities adopt policies and pursue recovery pathways that alleviate existing inequities in hazard risk will have important implications for social equity and well-being across society.

Another crucial area of inquiry in the aftermath of the Marshall fire is how these communities incorporate policies that are intended to improve climate resilience, such as land use policies and residential energy efficiency codes. Land use regulations can include hazard-resistant standards, such as defensible space and fire-resistant building materials, which reduce household and community risk from future disasters (Intini et al., 201910; Miller, 201711). They also play an important role in climate mitigation by mandating increased energy efficiency to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Enker & Morrison, 202012). Within the communities affected by the Marshall Fire, there was variation in both the pre-fire existence of land use regulations and the adoption and/or relaxation of those policies during the recovery process (Ellery et al., 202313). Understanding how public opinion around these policies has evolved post-disaster can provide insights into opportunities and challenges for building resilience using local land use regulations.

Research Questions

We answered the following research questions:

Building Codes and Land Use Regulations: How does individual support for regulations that mitigate disaster risk and build climate resiliency—namely land use policy and energy efficiency codes—change over time? To what extent does that support vary between highly impacted individuals and those who were less impacted?

Disaster Impacts, Recovery, and Engagement through a Social Equity Lens: How have the impacts of the Marshall Fire varied across different groups (e.g., renters vs. homeowners, lower vs. higher income households, survivors with high levels of insurance vs. those with lower levels)? What obstacles keep community members from engaging in public decision-making processes that affect recovery and resilience?

Equitable and Inclusive Mitigation Practices: In jurisdictions where Marshall Fire victims were exempt from more stringent building code regulations, what factors have influenced the voluntary implementation of these codes in residents’ rebuilding decisions? What role have incentives and rebates played in shaping rebuilding outcomes, and how do rebuilding outcomes vary across social groups?

Answers to these questions will guide local and state-level decision-makers as they develop strategies to increase adoption and uptake of mitigation and resilience-promoting building codes in post-disaster settings.

Research Design

The Marshall Fire Recovery and Resilience Working Group developed the Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey in collaboration with more than 30 climate and hazards specialists with various areas of expertise, including emergency management, long-term recovery and resilience, climate and recovery equity, local government, and community organizations. A key objective of early survey efforts was to implement one “unified” survey rather than a large number of smaller and more specialized surveys. This allowed researchers to generate high-quality, transdisciplinary data with the potential to advance science in multiple domains and assist recovery and resilience building efforts. In addition, this approach minimized burdens on impacted residents and maximized potential benefits for research participants through trauma-informed and ethical research practices. The resulting survey instruments cover a range of different topics relevant to understanding how the Marshall Fire has impacted Colorado communities and how the recovery process is unfolding over time (Dickinson et al., 202214). A survey explainer, as well as technical reports and other public-facing dissemination products, are available on the project website.

Study Site and Access

Our study area included the three jurisdictions most affected by the Marshall Fire: the City of Louisville, the Town of Superior, and areas of Unincorporated Boulder County. Several members of the research team are either residents of, or have personal or professional connections to, the fire-impacted areas. Throughout the process, our team engaged with community-based organizations and local governments to inform our survey design and implementation to ensure our instrument was trauma-informed and would collect data that would be helpful to the public, decision-makers, and researchers. For the second wave of the survey, our relationship with Boulder County allowed us to expand our survey sample to include residents who had signed up for fire-related aid from the county. Our research team has taken opportunities to disseminate our findings and key takeaways from the survey to support the communities’ recovery, such as presenting findings at multiple academic conferences, participating in interviews on podcasts and in local newspapers, and providing public testimony at the Colorado General Assembly supporting legislation to establish remediation standards for residential premises that sustain smoke and/or ash damage due to a fire. In fall 2023, we convened community, government, and academic groups to share findings from the first two waves of the survey, discuss next steps, and solicit feedback on the Wave 3 survey plans.

Survey

Sampling Strategy and Implementation

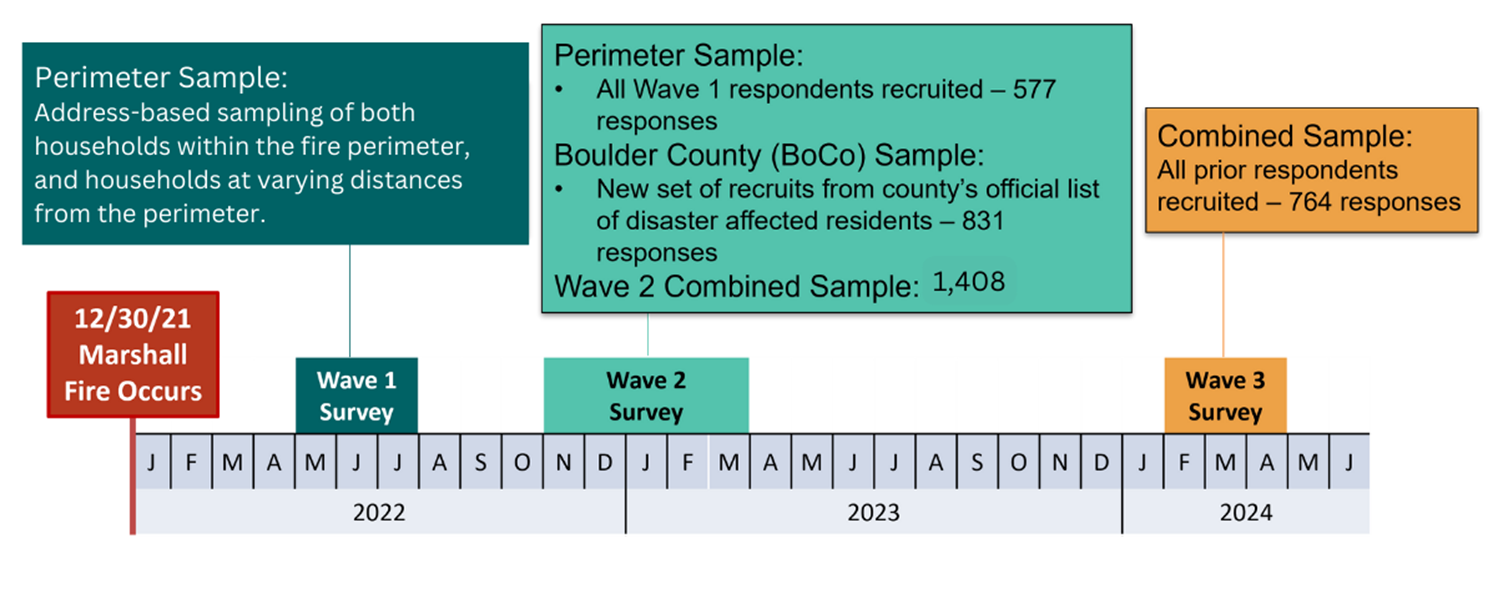

The Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey was conducted online through the survey software Qualtrics. We initially recruited participants by sending letters sent to their physical address. We also used a mail processing center to identify forwarding addresses for displaced residents. The letters contained a QR code and URL address that provided access to the online survey. For subsequent survey waves, we recruited respondents using the email address they provided from their prior survey response. During Wave 2, we were provided email addresses for additional respondent recruitment through Boulder County’s official list of fire affected residents. Upon accessing the online survey, respondents were shown a consent letter that explained the benefits and risks of participating in survey research, as well as ensuring the individual was at least 18 years old. A timeline of the survey sampling strategy and composition across waves is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey Timeline

The Wave 1 survey ran from May 12 to July 19, 2022. with participants. We targeted two groups to participate in Wave 1: First, we recruited all households whose residences were within the burn perimeter. Second, we recruited a random sample of households whose residences were varying distances from the perimeter to provide a comparison group based on level of fire impact. The total sample area covered most of the City of Louisville and the Town of Superior, as well as parts of Boulder County.

The Wave 2 survey was conducted between November 12, 2022, and April 25, 2023, spanning a period before and after the one-year anniversary of the Marshall Fire. All Wave 1 respondents were invited to complete the Wave 2 survey. During Wave 2, the research team recruited additional participants, known as the “BoCo Sample,” which draws from Boulder County’s official list of disaster-affected residents who were not part of the Wave 1 perimeter-based panel (referred to as the “Perimeter Sample”). Therefore, in Wave 2 survey respondents included both the Perimeter Sample and the BoCo Sample.

The Wave 3 survey was conducted between February 24 and April 12, 2024, shortly after the two-year anniversary of the Marshall Fire. The participants recruited for the Wave 3 survey consist of both Perimeter panel and BoCo panel participants (referred to as the “Combined Sample”). Table 1 describes the total survey recruits and response rates during each wave of the survey.

Table 1. Marshall Fire Unified Survey Response Rates Across Three Waves

(Wave 2) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Survey Measures

We developed the online survey with display logic that ensured respondents were only asked questions that were relevant to their recovery context. During the first wave survey, for example, we asked respondents to indicate the impact that the fire had on them (i.e., no damage, damaged and living in the home post-fire, damaged and not living in the home post-fire, or complete loss of home). Subsequent questions depended on how the respondent answered the fire impact question and what jurisdiction they were living in at the time of the first survey. The first wave survey was the only time we asked respondents to report their fire impact category and demographics. Other survey measures were repeated across the survey waves to track longitudinal experiences. Each survey consisted of multiple sections that spanned a variety of topics, such as:

- Information about residents’ homes and fire impacts

- Evacuation and emergency alerts

- Impacts on pets and companion animals

- Environmental impacts after the fire

- Remediation and home cleaning post-fire

- Rebuilding, reconstruction, and relocation decisions

- Participatory processes and policy support

- Reminders of the event

- Social capital, connections, and support

- Physical health, mental health, and resilience

- Worldviews and climate change beliefs

- Demographics

The survey contained both open and closed text responses, allowing for both quantitative and qualitative analysis of survey data.

Survey Sample

Table 2 shows the survey sample across the three waves by respondents’ place of residence, the impact of the Marshall Fire on their home, and their housing tenure status.

Table 2. Marshall Fire Unified Survey by Wave, Place of Residence, and Housing Characteristics

| Place of Residence | ||||||||||

| Unincorporated Boulder County | ||||||||||

| Louisville | ||||||||||

| Superior | ||||||||||

| Fire Impact on Home Category | ||||||||||

| Complete Loss | ||||||||||

| Home Damaged, Respondent No Longer Living There | ||||||||||

| Home Damaged, Respondent Still Living There | ||||||||||

| Home Not Damaged, Respondent Still Living There | ||||||||||

| Housing Tenure Category | ||||||||||

| Homeowner | ||||||||||

| Renter | ||||||||||

Overall, 764 respondents completed the third wave of our Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey. The survey sample includes residents in three jurisdictions affected by the Marshall Fire who experienced varying levels of damage. Nearly 50% of respondents from Wave 2 completed the Wave 3 survey. Attrition was higher among respondents who lived in unincorporated Boulder County than it was among respondents living in Louisville or Superior. It was also higher among respondents whose homes were damaged than it was among respondents whose homes were completely lost or had no damage and higher among renters as compared to homeowners.

Table 3 presents socio-demographic characteristics of the Wave 3 sample—specifically, respondents’ gender, age, race/ethnicity, and household income. Some respondents chose not to report their socio-demographic characteristics, especially household income.

Table 3. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Wave 3 Survey Participants

| Gender (n = 761) |

Female | ||

| Male | |||

| Non-Binary/Other/Decline | |||

| Age (n = 709) |

18-34 | ||

| 35-54 | |||

| 55+ | |||

| Race/Ethnicity (n = 703) |

White Non-Hispanic | ||

| People of Color | |||

| Income (n = 610) |

Less than $75,000 | ||

| $75,000-$149,000 | |||

| $150,000-$200,000 | |||

| $200,000 or more | |||

Data Analysis Procedures

Raw survey data were exported from Qualtrics as a .csv file for data cleaning and analysis. Data were analyzed using STATA and R Studio. Raw survey data was cleaned to include only complete responses. Survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics to characterize the sample and calculate frequencies for question responses. In addition, we used multivariate and longitudinal techniques to look at differences in recovery outcomes across groups and time.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB #22-0085) on February 14, 2022. Our data collection and management protocols are designed to safeguard participants’ confidentiality and anonymity. All survey respondents were offered informed consent information and compensated with a gift card to a local grocery store or restaurant if they completed the survey.

Our study team has a demonstrated commitment to working collaboratively with community members, decision-makers, and broader research collectives to conduct responsive and rigorous research-to-action. PI Dickinson is a Louisville resident. While her home was spared by the fire, she saw its impacts on her community firsthand and recognized the need for rigorous, responsive, trauma-informed research to examine a wide range of disaster impacts and recovery processes. She quickly reached out to co-authors Crow (an expert in disaster policy who was also raised in Boulder County), Albright, and Rumbach, and they formed the Marshall Fire Recovery and Resilience Working Group with the goal of collecting perishable data on disaster impacts, the recovery process, and policy change over time.

On January 19, 2022, a few weeks after the fire, our team attended a virtual convening workshop held by the Natural Hazards Center and learned that several other researchers were interested in collecting survey and interview data with affected communities. To minimize the burden on the community and maximize the scientific value of post-Marshall Fire survey research, Dickinson convened the Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey Working Group, a team of about 30 researchers who worked together to develop and implement one comprehensive survey instrument. Our team also engaged with local and state governments as well as affected community groups to explain the research project’s objectives and get input on survey content and implementation.

Results

The results below focus on the research questions described in this report. Full results from the Wave 3 survey are publicly available in the Wave 3 Technical Report (Dickinson et al., 202415), which is published on our project website, and includes insights from all sections of the survey.

Building Codes and Land Use Regulations

In Louisville and Superior, local governments allowed fire victims who had lost their homes to choose which energy efficiency code—the 2021 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) or the previous 2018 IECC—would be used to rebuild their home. Whether fire victims should be exempt from the 2021 IECC generated extensive public debate, as the newer code had been adopted only a few months before the disaster in Louisville and was in the process of being adopted in Superior. The 2021 code continues to be the required energy code for non-Marshall Fire victims in Louisville and Superior. In contrast, Boulder County’s energy code had been in place since 2016.

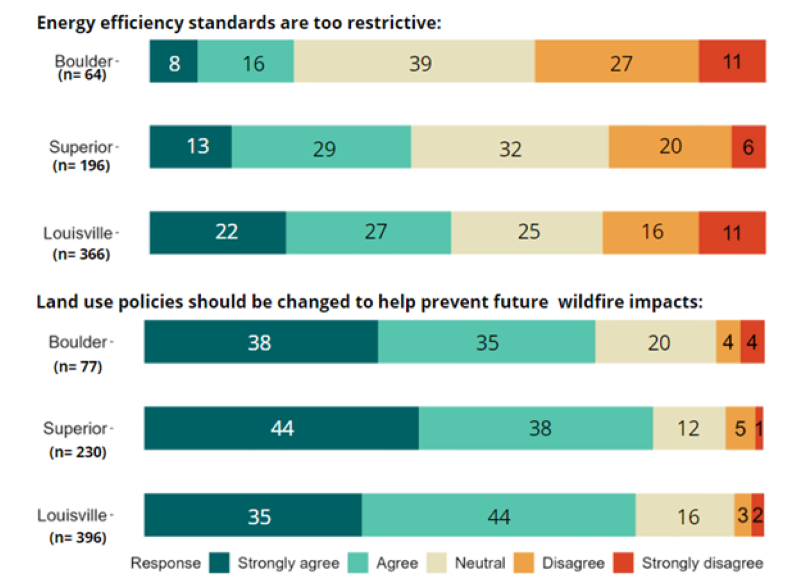

Across all three waves of our survey, we asked respondents about their agreement with the following statement: Energy efficiency standards in place before the Marshall Fire are too restrictive, making rebuilding too expensive. Overall, at Wave 3, around 43% agreed or strongly agreed with that statement. Figure 2 shows how these sentiments vary by their place of residence. The belief that the energy efficiency standards were too restrictive was strongest in Louisville, with 49% of respondents either strongly agreeing or agreeing with the statement. In Superior, 42% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed, whereas in unincorporated Boulder County the majority of the respondents were neutral, with 24% either strongly agreeing or agreeing. When asked about level of agreement with the statement “Land use policies should be changed to help prevent future wildfire impacts,” respondents more frequently expressed agreement with this statement than they did about whether energy efficiency standards were too restrictive.

Figure 2. Respondent Views of Energy Efficiency and Land Use Policies at Wave 3, by Percentage

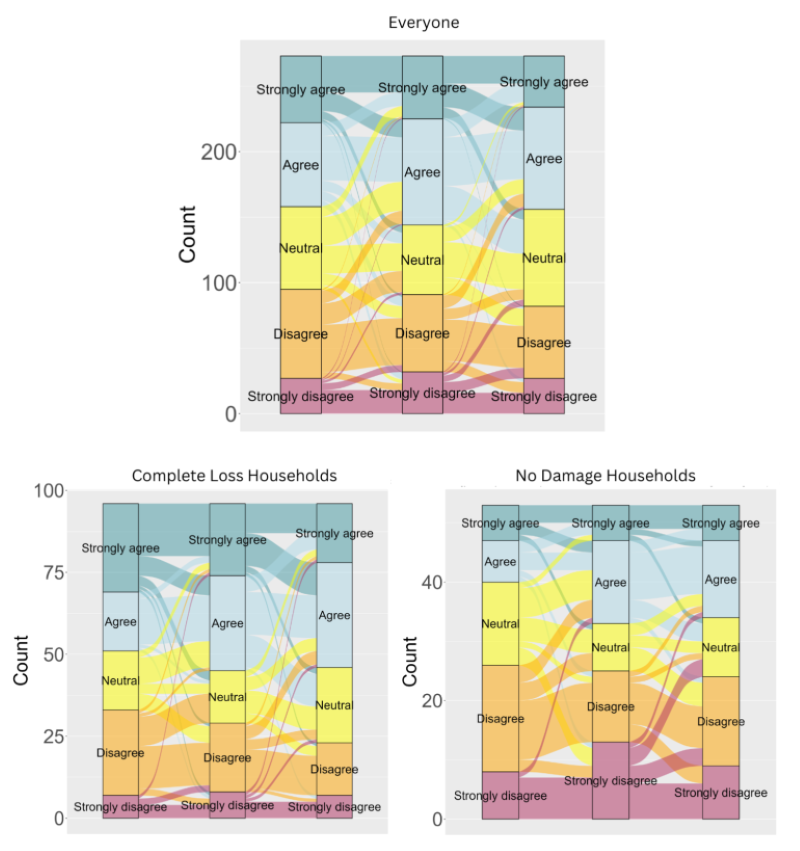

Across all three waves of our survey, respondents’ opinions about energy efficiency standards have differed depending on the way the fire impacted their home and their place of residence. As shown in Figure 3, residents whose homes were not damaged by the Marshall Fire had more diverse opinions about whether standards were too restrictive. Meanwhile, those who had experienced complete loss were much more likely to indicate they agreed with the statement that energy standards were too restrictive.

Figure 3. Alluvial Plot of Change Over Time in Respondent Views of Energy Efficiency Standards, by Fire Impact on Home Category

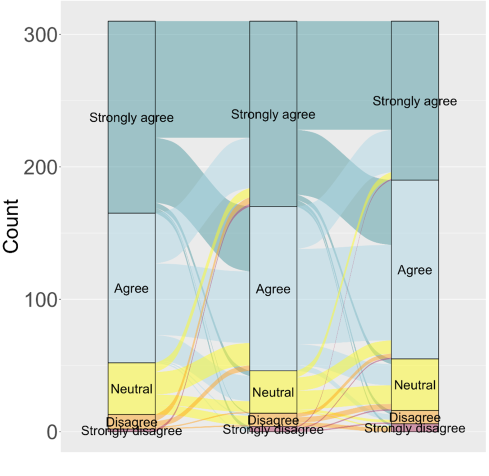

Respondents were also asked about their agreement with the following statement, “Land use policies, such as zoning and open space management, should be changed to help prevent future wildfire impacts.” As Figure 4 shows, respondents strongly supported this statement, especially compared to the energy code question. Their support was consistent across time.

Figure 4. Alluvial Plot of Change Over Time in Respondent Views of Using Land Use Policy to Prevent Wildfire Impacts

Disaster Impacts, Recovery, and Engagement Through a Social Equity Lens

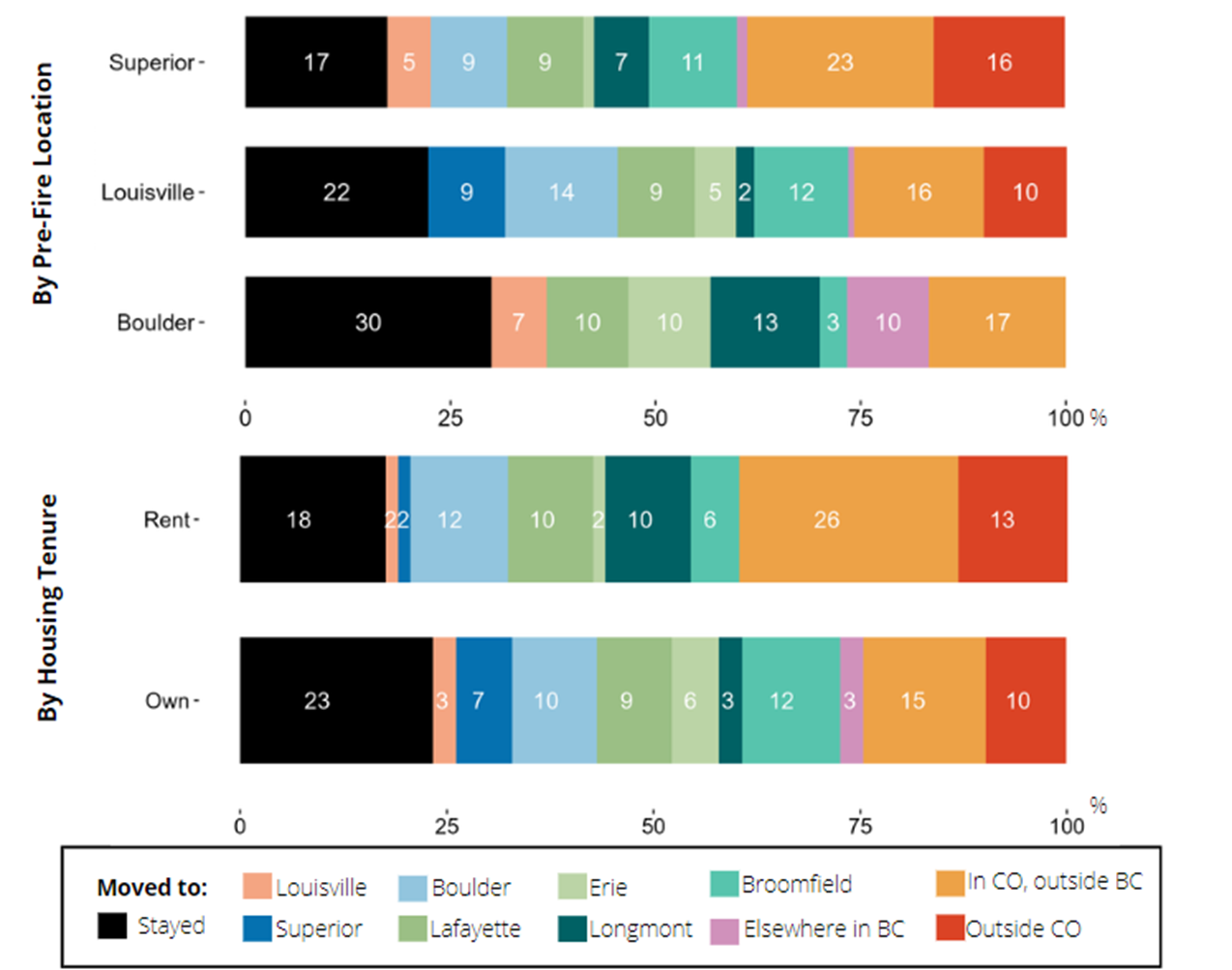

People who lost homes or experienced significant damage have had to navigate complicated decisions about whether to rebuild, remediate, or relocate. In Wave 3, we asked the 244 respondents who had not returned to live at their pre-fire addresses about their current locations post-fire. This group of respondents included 30 people who at the time of the fire were living in Unincorporated Boulder County, 139 in Louisville, and 75 in Superior. Overall, 61% of respondents who were still displaced at Wave 3 were still living in Boulder County, 18% were living outside of Boulder County in nearby jurisdictions (Erie, Longmont, Broomfield), and 11% had moved out of state. Unincorporated Boulder County residents were more likely to be living in the same jurisdiction than Louisville and Superior residents. We also found that renters were more likely than homeowners to be living in a different jurisdiction and to have moved farther away (outside of Boulder County or out of state). Figure 5 depicts the displacement breakdown by jurisdiction and by housing tenure.

Figure 5. Current Place of Residence Among Respondents at Wave 3, by Their Pre-Fire Jurisdiction and Housing Tenure

Our Wave 3 sample included 249 respondents who were homeowners who had completely lost their homes. Of this group, which we refer to as “complete-loss homeowners,” 23 (9%) had sold their properties, 111 (44.6%) had completed rebuilding and moved back home or had been issued a certificate of occupancy, and 115 (46%) were still rebuilding and had not been issued a certificate of occupancy yet. On the survey, we asked complete-loss homeowners to describe where they were in the process of rebuilding their home, allowing them to choose among the categories outlined in Table 4.

Table 4. Current Rebuilding Stage Among Homeowners Who Lost Their Home in the Marshall Fire

| Demolition | |||

| Preconstruction activities, such as permitting, building design, and hiring/contract negotiation | |||

| Construction Phase | |||

| Construction complete and respondent is either back home or issued a certificate of occupancya | |||

| Sold Property | |||

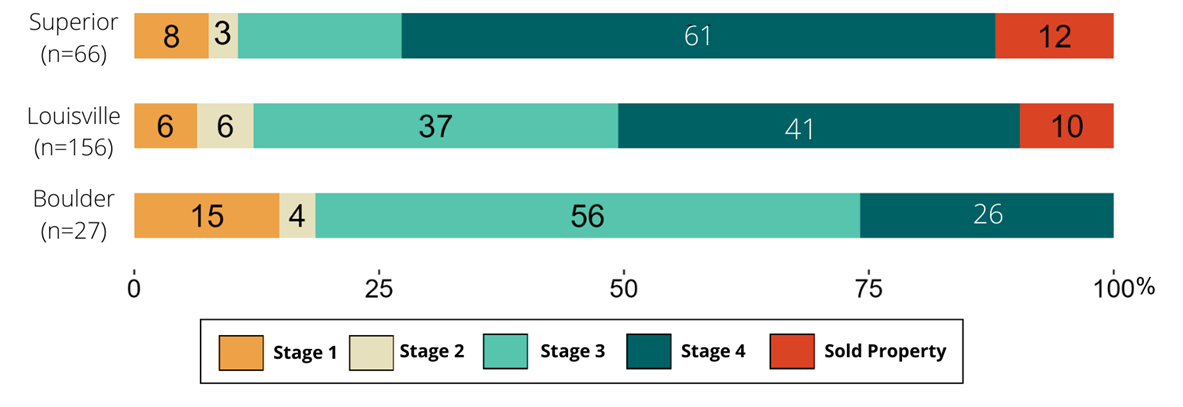

There were large differences across jurisdictions in rebuilding progress among complete-loss homeowners, as shown in Figure 6. In Superior, 61% of complete-loss respondents had rebuilt their homes and moved back, compared to 41% in Louisville and only 26% in unincorporated Boulder County. While smaller in number, it is important to note that some respondents had not begun the rebuilding process, ranging from 6% in Louisville to 15% in Unincorporated Boulder County.

Figure 6. Percentage of Complete-Loss Homeowners at Each Rebuilding Stage at Wave 3, by Jurisdiction

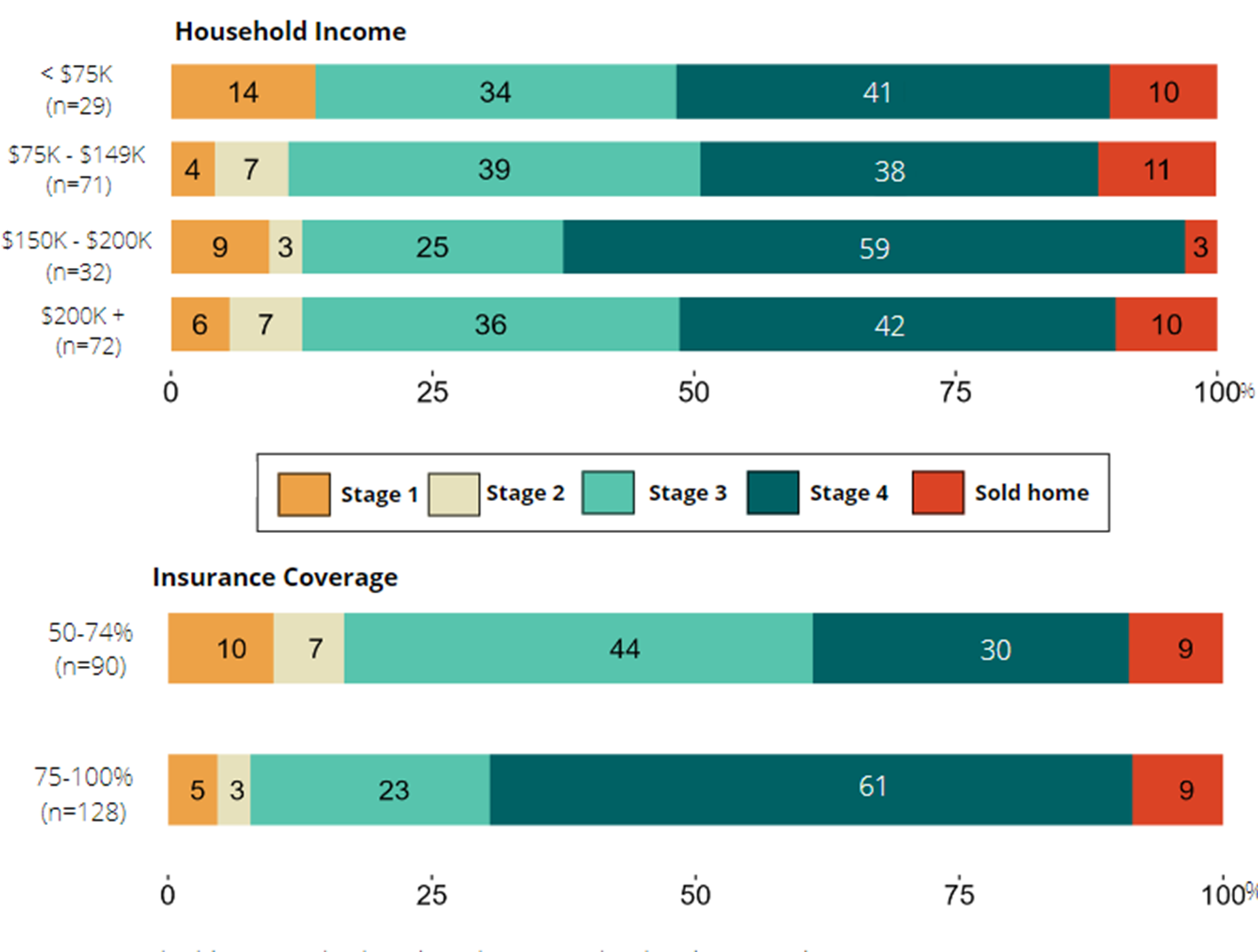

We also looked at how rebuilding stage varied by household income and by expected insurance coverage. As shown in Figure 7, households making less than $75,000 were more likely to be in the earlier stages of rebuilding, although these differences were less pronounced than they were in our Wave 2 sample. Respondents in the second highest income group ($150,000-$200,000) were the most likely to have completed rebuilding and moved back home and the least likely to have sold their properties, compared to both lower income and the highest income groups. Meanwhile, insurance coverage seems to be the clearest indicator of recovery progress, with households who have at least 75% of their rebuilding costs covered by insurance significantly more likely to be in Stage 4 of the rebuilding process compared to households with less insurance coverage.

Figure 7. Percentage of Complete-Loss Homeowners at Each Rebuilding Stage at Wave 3, by Household Income and Insurance Coverage

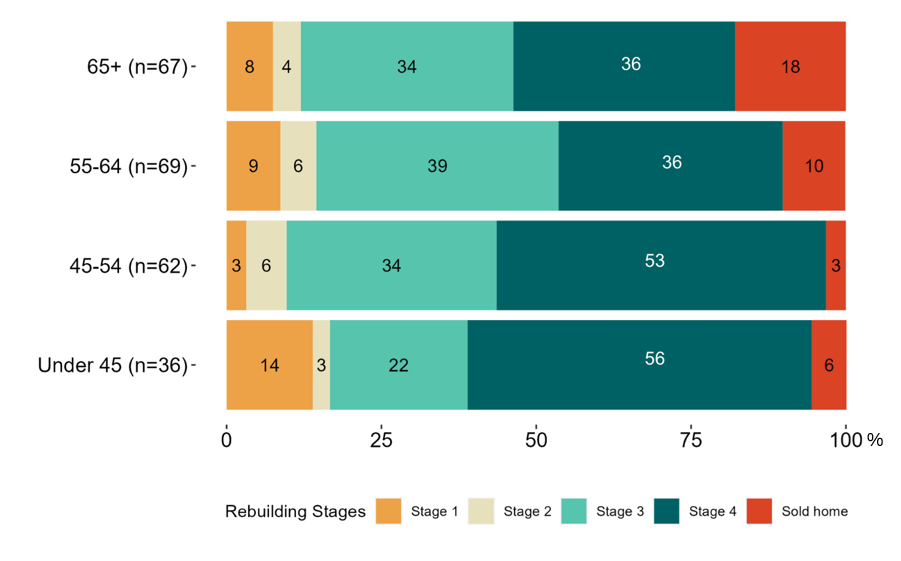

In addition to income and insurance, we also analyzed rebuilding progress by age group. As shown in Figure 8, adults over 65 years of age were the most likely to report selling their home altogether (18% of respondents in this group) compared to all other age groups. The youngest participants, under 45 years of age, were most likely to report that they were still in stage 1 of the rebuilding process (14%).

Figure 8. Percentage of Complete-Loss Homeowners at Each Rebuilding Stage at Wave 3, by Age Group

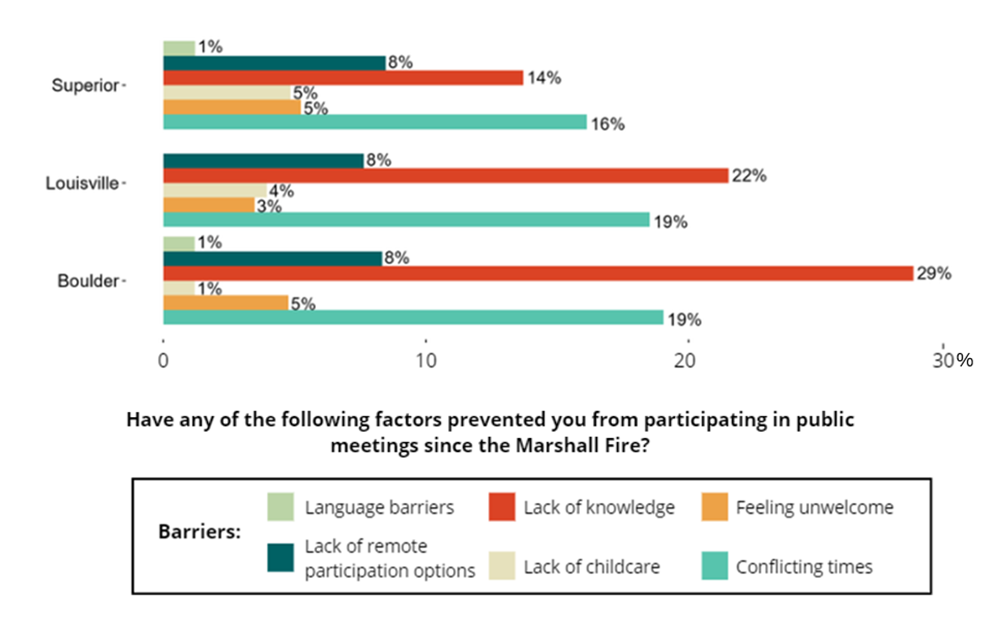

The Wave 3 survey included a question about barriers to participation in public meetings after the Marshall Fire, the results of which are shown in Figure 9. Lack of knowledge about public meetings was the most frequently cited obstacle to participation among respondents in Louisville and Superior, with 22% and 29% choosing this option, respectively. In Superior, respondents cited conflicting times as the most frequent factor preventing their participation. In Louisville and Boulder, time conflicts were the second most frequently listed barrier to participation.

Figure 9. Public Participation Barriers by Jurisdiction

Equitable and Inclusive Mitigation Practices

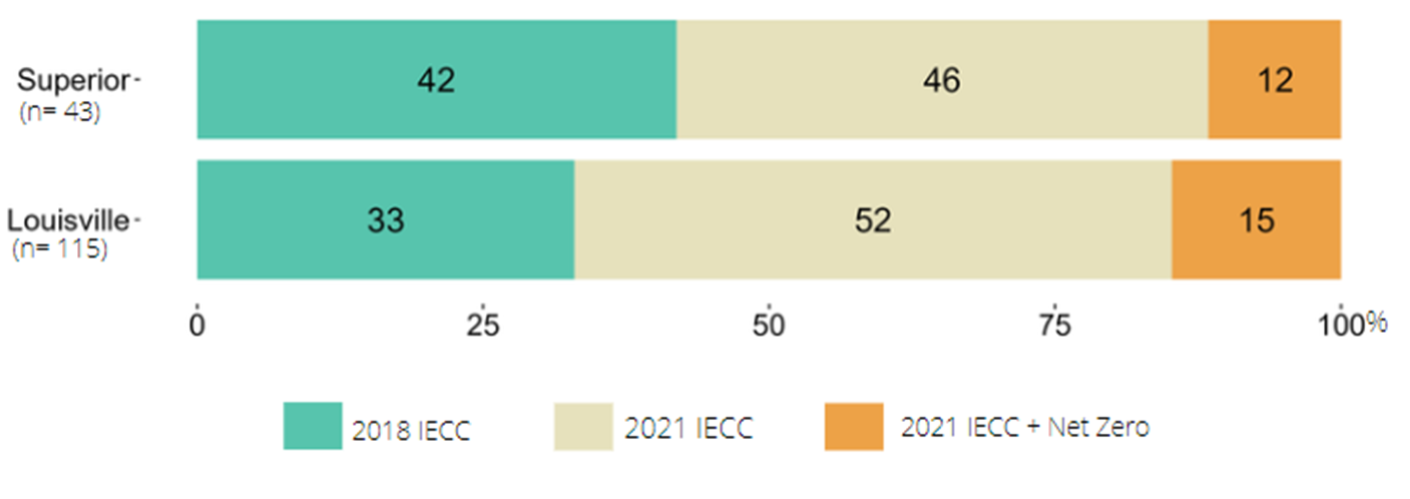

Complete-loss homeowners had to make decisions about how they would rebuild their homes, including decisions related to the energy efficiency standard that would be used in the design of their new homes, which had implications for carbon emissions and climate change mitigation. Fire victims in Louisville and Superior were allowed to choose between three energy efficiency codes: the 2018 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), the 2021 IECC, or the stricter version of the 2021 IECC known as the 2021 IECC with Net Zero. We asked respondents which standard they ultimately selected, and Figure 10 shows the results. In Louisville and Superior, more than half of complete-loss homeowners who were rebuilding opted for the 2021 IECC, with an additional proportion opting to build to the most efficient net zero standards. All homeowners in Unincorporated Boulder County were required to build to the Boulder County BuildSmart code, with an optional upgrade to BuildSmart Zero Net Energy. The Boulder County BuildSmart code is distinct from the IECC. At Wave 3 of this survey, 53% of Unincorporated Boulder County respondents who were rebuilding had opted to upgrade to the BuildSmart Zero Net Energy.

Figure 10. Percentage of Complete-Loss Homeowners Selecting Each Energy Code Option Available for Rebuilding in Superior and Louisville

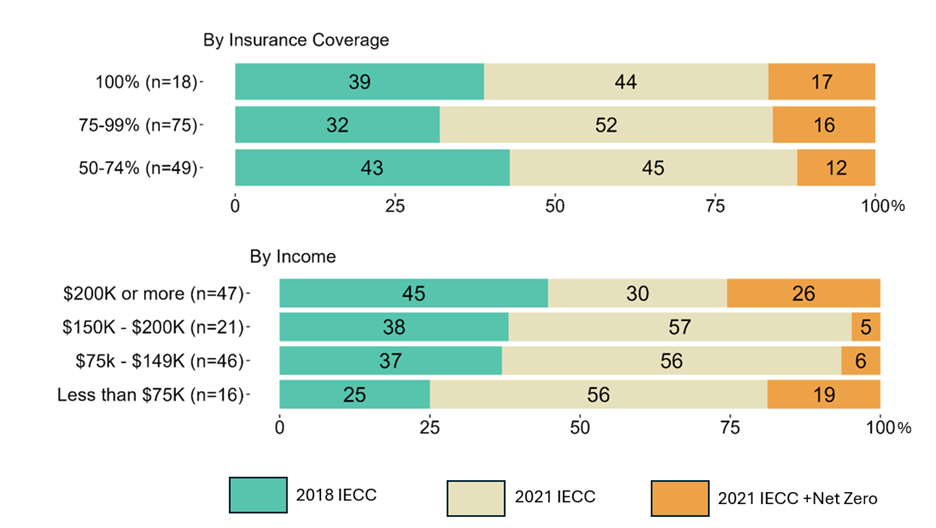

We analyzed how energy code selection differed across insurance coverage, income group, and funding sources. As Figure 11 shows, across all income and insurance groups, building to the 2021 IECC was more common than building to the 2018 code. Homeowners with less insurance coverage were somewhat less likely to adopt the 2021 code. Building to the 2021 IECC with Net Zero was most frequently reported in the highest and lowest income group, although we note that the lowest income group has a small sample size.

Figure 11. Percentage of Complete-Loss Homeowners in Louisville and Superior Selecting Each Energy Code Option Available for Rebuilding, by Insurance Coverage and Household Income

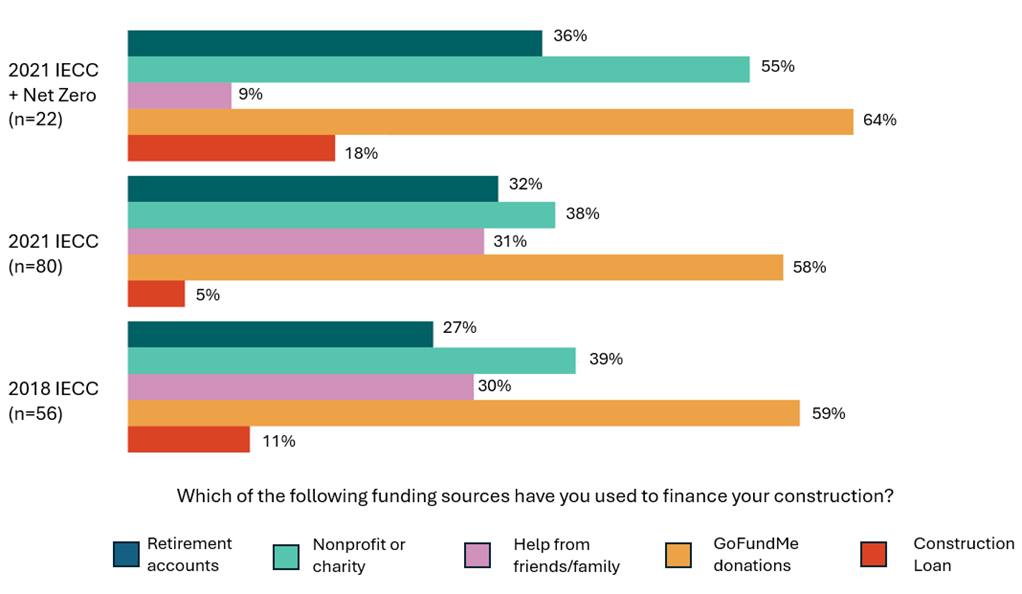

Figure 12 illustrates the different funding sources—other than insurance payouts—respondents utilized to finance their rebuild, broken down by the energy code they selected. Not surprisingly, insurance payouts were a unanimous funding source across all energy code groups. Receiving help from friends or family was least commonly reported by those who selected the 2021 IECC with Net Zero (9% versus 30% or more in the other energy code groups), but this group was more likely to have received funding from nonprofits or charities or home construction loans. Across all groups, GoFundMe donations and retirement funds were the most frequently used financial resource for rebuilding after insurance payouts.

Figure 12. Percentage of Complete-Loss Homeowners in Louisville and Superior Using Each Available Funding Source to Rebuild Their Home, by Energy Code Selection

Discussion

This survey allowed us to follow respondents’ experiences two years after the Marshall Fire, identifying successes and challenges that can inform ongoing recovery and hazard mitigation practices locally and in other areas. At the Wave 3 survey, communities had made significant progress in recovery. Among complete-loss homeowners, 43% had finished rebuilding and moved back home. At the same time, rebuilding outcomes varied considerably across jurisdictions, with the lowest rates of rebuilding in Boulder County and the highest in Superior. A smaller but notable set of complete-loss households (about 8%) were “stuck” and had not begun rebuilding. Insurance coverage appears to be a key factor associated with rebuilding outcomes. Complete-loss households whose insurance is expected to cover 75% or more of their rebuilding costs are twice as likely to have completed rebuilding than those households with lower levels of insurance coverage.

Another important dimension of inequity is age. Respondents over 65 years of age most frequently reported selling their property at two years post-fire instead of rebuilding, and younger respondents (under 45 years of age) were the least likely to have started rebuilding. Understanding why the oldest and youngest respondents may not decide to take on the rebuilding process could illuminate opportunities for policymakers to provide equitable resources to these groups in other disaster contexts.

Our results also indicate special challenges for people who were renting at the time of the Marshall Fire. Renters were more likely to have left their community after the fire than homeowners. Moreover, they were also more likely to have left the entire county. Prior analysis of Wave 2 data also showed that renters were less engaged in public decision-making processes. Renters in our survey sample were younger, reported lower incomes, and were more racially diverse than homeowners. Addressing renters’ specific challenges is an important area for emergency managers and local decision-makers to consider in disaster recovery efforts.

In Louisville and Superior, most complete-loss homeowner respondents who were in the rebuilding process opted to rebuild to a more efficient energy code than required. However, the data we currently have around selected energy efficiency codes could be skewed to reflect the choices of individuals with greater access to financial, social, or other forms of capital that allow them to have begun or completed reconstruction at two years –post-fire. Understanding the energy code selection of groups that have not been able to progress to the later stages of rebuilding yet would provide a fuller view of inequities in hazard mitigation practices.

Conclusions

Implications for Practice or Policy

The Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey has provided insight into which groups of fire-impacted individuals are falling behind in disaster recovery. These findings can be used to identify additional services and outreach activities that are needed to achieve equitable rebuilding and resilience outcomes. Below we describe these policy implications in more detail.

Increase Outreach to Renters: Policymakers and emergency managers could strategically engage renters, in particular, to understand why displacement was more common in this group after the Marshall Fire. Policy discussions should focus on what would help renters return to Boulder County (if desired) and how remaining in their community could be made more feasible in a future disaster.

Identify Barriers for “Stuck” Homeowners Who Are Still Rebuilding: Among homeowners that experience a complete loss of their home, there is a group that remains “stuck” in their rebuilding progress. While limited insurance coverage has been an obvious barrier for rebuilding, it is critical to understand the other reasons why these homeowners have not been able to rebuild more than 2 years after the disaster, as well as how to address these obstacles.

Offer Flexibility When New Building Codes and Disasters Coincide: Our results also offer lessons on hazard mitigation policy. Across all 3 waves of the survey, respondents were more supportive of using land use policies rather than energy efficiency standards for hazard mitigation. This suggests that local officials can expect heightened pushback to newer building codes in the wake of a disaster, and it may be beneficial for decision-makers to work proactively to provide additional flexibility and incentives when disasters and newer building codes co-occur. Moreover, respondents were generally more supportive of land use policy versus energy efficiency standards likely because energy efficiency standards would affect them at the individual level whereas land use policy involves decisions over public land. Energy efficiency standards that were in place longer than newer policies were less likely to be described as overly restrictive, even though many residents ultimately built to a stricter energy efficiency code.

Offer More Flexible Opportunities for Public Engagement: Our results also offer lessons on public engagement. First, the majority of respondents who were not able to participate in a public decision-making process indicated that they were not able to participate due to conflicting times and lack of knowledge. Both of these obstacles are ones that policymakers and local officials could directly address in the near term by offering additional meeting times, ways to join meetings, and making resources about the meeting topics more readily available.

Limitations

While this survey had a large sample size of respondents over time, there are limitations to this research. First, generalizing the results to populations other than the respondent sample should be done cautiously. Individuals with particularly positive or negative experiences may have been more inclined to participate in our research. We also saw attrition in survey participation over time, with only 50% of participants completing all three waves of the survey. Attrition was higher among Boulder County residents, those whose homes were damaged but not destroyed, and renters. Our survey was only offered in English, which likely means it failed to include households headed by non-English speakers. As a result, linguistic isolation is not a dimension of social inequity we could evaluate.

Future Research Directions

The results presented here include a snapshot of descriptive data derived from a rapid analysis of Wave 3 survey results. Our research team will continue to analyze these data in more depth through longitudinal and multivariate statistical analyses along with thematic analysis of qualitative data. These analyses will provide insights into the factors associated with recovery progress, policy engagement and support, physical and mental health, and other key outcomes over time. Our ongoing research efforts will be supported by new funding from the Joint Fire Science Program, beginning in September 2024 and concluding in August 2026. This research project, titled “Colorado's Marshall Fire: Impacts and Recovery Over Time Through the Lens of Social Equity” will leverage a collaborative community-engaged research approach to further explore how the fire’s social and economic impacts, access to recovery resources, and recovery outcomes have varied for different groups across time (Dickinson & Crow, 2024-202616). We will investigate these research questions through interviews, deeper analyses of existing longitudinal survey data, additional follow-up surveys, and a public records review. Ultimately, this research effort will paint a nuanced picture of the recovery realities, barriers, and opportunities that individuals in the Marshall Fire-impacted communities are experiencing, and, consequently, what gaps remain to reach an equitable recovery.

Acknowledgments. We are grateful to the many contributors to the collective Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey, including many academic partners, local and state governments, and community organizations. This survey effort has been funded by the National Science Foundation (grant #2220589), the Natural Hazards Center, the JPB Environmental Health Fellowship, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Higher Education Program, the City of Louisville, and generous anonymous donations to the Colorado School of Public Health’s Dean’s Initiative Fund. We are also deeply grateful to the community members in Louisville, Superior, and Unincorporated Boulder County who have participated in our survey effort and contributed their time and insights to help us learn about the impacts of the Marshall Fire and the recovery process.

The research for this report was jointly funded by the Natural Hazards Center Mitigation Matters Research Award Program and the FEMA Higher Education Program. We submitted a final report to FEMA that is similar to the one on this website. The report therefore adheres to the following criteria:

The FEMA Higher Education Program funds multidisciplinary applied research in support of advancing the practice of Emergency Management. Research proposals are subject to a competitive review process and funded projects must align with the FEMA Strategic Plan. The Higher Education Program disseminates the final written products for informational purposes and to stimulate or advance conversations which are relevant to the Emergency Management profession. While the final written product was funded and approved for public distribution by FEMA, the analysis, conclusions, and recommendations contained in the materials are attributable solely to the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by DHS, FEMA, or the Higher Education Program.

References

-

Liu, Z., Wimberly, M. C., Lamsal, A., Sohl, T. L., & Hawbaker, T. J. (2015). Climate change and wildfire risk in an expanding wildland–urban interface: A case study from the Colorado Front Range Corridor. Landscape Ecology, 30(10), 1943-1957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-015-0222-4 ↩

-

Colorado Resiliency Office. (n.d.). Colorado Resiliency Framework. www.coresiliency.com ↩

-

Fothergill, A. (2004). Poverty and disasters in the United States: A review of recent sociological findings. Natural Hazards, 32, 89-110. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:NHAZ.0000026792.76181.d9 ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). QuickFacts: Colorado, Boulder County, Colorado. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/CO,bouldercountycolorado/PST045222 ↩

-

Boulder County. (2023). Boulder County Sustainability Plan. https://assets.bouldercounty.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/BoCo-2022-Sustainability-Plan.pdf ↩

-

City of Louisville. (2020). Sustainability action plan.

https://www.louisvilleco.gov/home/showpublisheddocument/28886/637376646025230000 ↩ -

Town of Superior. (2022). Sustainability action plan. https://www.superiorcolorado.gov/home/showpublisheddocument/20279/63782857715533000 ↩

-

Agyeman, J., Bullard, R. D., & Evans, B. (2003). Just sustainabilities: Development in an unequal world (1st ed.). MIT Press. ↩

-

Tierney, K. (2007). From the margins to the mainstream? Disaster research at the crossroads. Annual Review of Sociology, 33. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131743 ↩

-

Intini, P., Ronchi, E., Gwynne, S., & Benichou, N. (2019). Guidance on design and construction of the built environment against wildland urban interface fire hazard: A review. Fire Technology, 56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-019-00902-z ↩

-

Miller, S. R. (2017). Planning for wildfire in the wildland-urban interface: A guide for western communities. Urban Lawyer, 49, 207-266. ↩

-

Enker, R. A., & Morrison, G. M. (2020). The potential contribution of building codes to climate change response policies for the built environment. Energy Efficiency, 13(4), 789-807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-020-09871-7 ↩

-

Ellery, M., Javernick-Will, A., Liel, A., & Dickinson, K. (2023). Jurisdictional decision-making about building codes for resiliency and sustainability post-fire. Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability, 3(4), 045004. https://doi.org/10.1088/2634-4505/ad02b8 ↩

-

Dickinson, K., Devoss, R., Albright, E., Crow, D.A., Rumbach, A., Bean, H., Fraser, T., Reid, C., Bolhari, A., Welton-Mitchell, C., Andre, C., Aldrich, D., Morss, R., Whelton, A., Javernick-Will, A., Irvine, L., du Bray, M., Rubenfeld, S. & Tillema, S. (2022). Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey, in RAPID: Can Big Ideas About Resilience Survive the Reality of a Disaster? Built Environment Policy and Recovery After the Marshall Fire. DesignSafe-CI. https://doi.org/10.17603/ds2-0yc8-4h27 ↩

-

Dickinson, K., Albright, E., Crow, D., Gershon, N., Javernick-Will, A., Jeschke, N., Kadota, M., Reid, C., Rosenow, A., Rumbach, A., Walters, H., & Whelton A. (2024, July). Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey Wave 3 Technical Report. https://www.marshallresilience.com/what-weve-learned ↩

-

Dickinson, K., & Crow, D. 2024-2026. Colorado's Marshall Fire: Impacts and Recovery Over Time Through the Lens of Social Equity [Grant]. Joint Fire Science Program. ↩

Dickinson, K., Walters, H., Crow, D., Albright, E., Rumbach, A., Rosenow, A., Kadota, M., Jeschke, N., Javernick-Will, A., & Gershon, N. (2025). Colorado’s Marshall Fire: Recovery, Mitigation, and Resilience Through a Social Equity Lens. (Natural Hazards Center Mitigation Matters Research Report Series, Report 22). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/mitigation-matters-report/colorados-marshall-fire