The Use of Disaster Information and Communication Technology Among At-Risk Populations in U.S. Virgin Islands

Publication Date: 2022

Executive Summary

Overview

Access to and knowledge of technological tools can contribute greatly to post-disaster community resilience. Technological tools aid in the swiftness and depth of recovery within a community by helping connect authorities and the public to exchange information. This study aimed to discover what technology public health organization leaders recommend and use and what technology at-risk populations are aware of and report using. Much of the community focus was on residents of public housing communities, as they are often the most vulnerable communities following a disaster. They often rely on word of mouth or other nontechnological mechanisms to learn of available food, shelter, and other support. It is important to understand the tools individuals in these communities have used to connect them with public health workers and services.

The U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) are susceptible to different types of disasters: hurricanes and tropical storms, earthquakes, and tsunamis. Post-disaster community resilience can be greatly increased by utilizing available technologies, such as solar chargers, mobile applications, and websites. Through interdisciplinary mixed-methods research, this study seeks to uncover the level of technology use and awareness that exists within at-risk populations and public health organizations on the island of St. Croix.

Research Questions

The research questions that guided this study were: (a) What do leaders of public health organizations feel community members should have in terms of awareness about technologies used for disaster response? (b) What technological tools do at-risk populations report using and what competencies do they have to use these tools? Are there barriers to using these technologies? and (c) What disparities exist between at-risk population use of disaster-related technological tools and current public health organization technological tools?

Research Design

This study utilized a mixed method design that focused on answering the three research questions. We conducted interviews with two leaders of public health organizations to understand the technologies and methodologies that are in place in the event of a disaster. The interview responses were used to inform the creation of a questionnaire. We used this questionnaire to survey individuals from targeted housing communities (N=166).

Findings

The study findings highlight several noteworthy facts regarding technological awareness and use. First, leaders of public health agencies revealed that there are several applications and technologies available to residents of the USVI for disaster recovery. Both the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the American Red Cross provide free, user-friendly disaster recovery applications for the public. In addition, there are Short Messaging Service (SMS) and push notifications that residents can sign up for to receive emergency alerts and other important communications. Second, the survey results indicate that most residents have access to internet services and possess a knowledge base to use electronic applications. The majority of participants reported having difficulties accessing several technologies, including backup batteries, online services and websites, ham radio, satellite radio, SMS, and solar power. Eleven of the 166 participants indicated that they had no trouble acquiring any of the listed technologies. Lastly, we have not yet assessed the third research question that asks whether a disparity exists between public health organization recommendations and the at-risk population use of information and communication technologies. We will explore this question in future research.

Public Health Implications

This study has important public health implications. First, it will provide public health providers with insight into whether a disconnect exists between their recommended pre- and post-disaster technologies and the community’s awareness and usage of those technologies. Specifically, the results of this study can be used to inform leaders of public health organizations on the barriers which prevent at-risk groups from using these technologies. This can help these agencies develop interventions to increase the awareness of and access to technological tools within public housing communities. The results may also lead to the creation of policies or a new app specific to improving communication and information sharing.

Second, the results of the study may also highlight areas for improvement within the community-public health provider relationship. It is the aim of the researchers to create a model for assessing a community’s technological awareness and usage of post-disaster technology while increasing the community’s connection to its public health providers. This model can help to bridge a gap and increase future communication between residents and public health leaders.

Introduction

Situated in the Caribbean, the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) are susceptible to different types of disasters: hurricanes and tropical storms, earthquakes, tsunamis, and more. Historically, USVI has been most impacted by hurricanes; most recently, Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017. Hurricanes can interrupt the daily routines of affected people. For example, residents may lose access to food, medicine, or other resources that support their physical health. The ability to communicate with family and friends in the territory and beyond may also be cut off, which can contribute to anxiety or other mental health problems. Post-disaster community resilience can be greatly increased by utilizing available technologies, including solar chargers, mobile applications, and websites (Harrison & Williams, 20161). Access to and knowledge of technological tools can contribute greatly to a community’s ability to bounce back after disaster.

Technological tools aid in the swiftness and depth of recovery within a community by “enhancing the interconnectedness between the authorities and the public and by facilitating the rapid exchange of information” (Vos & Sullivan, 20142). There is currently no available assessment of disaster communication technology in the USVI. Through interdisciplinary mixed-methods research, this study sought to uncover the level of information and communication technology use and awareness among at-risk populations and public health organizations on the island of St. Croix. In addition, we documented the technology preferences and experience of public health leaders and members of at-risk populations.

Literature Review

Major hurricanes impact small islands both in the way they operate and in their future development (Popescu et al., 20203). In 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria ravaged the USVI within a span of two weeks. The long-term effects of those disasters are still being felt—almost five years later, there are still a number of homes that have blue tarps on them (Ambrose, 20194). Immediately after the hurricanes, daily life was severely impacted. Schools were closed, places of business closed (some permanently), families were displaced, and supply shortages were common. People relied on radio communications to learn where to obtain packages of food and supplies (Nieves-Pizarro, 20195). Communication and information sharing within the community was limited, and government organizations, researchers and public health agencies have recognized the use and importance of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) for effective disaster risk management at all four phases of disaster management (Firdhous, 20186; Vos & Sullivan, 2014). ICT has also been found critical for disaster response by National Disaster Organizations in Caribbean countries (Levius, 20177). ICTs are products and devices that help people and organizations interact with each other. Government agencies use different types of ICTs for disaster preparedness, response and recovery, such as Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEAs) used by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Trilogy Emergency Response Application (TERA) used in Asia, Serval project apps, satellite communications, social media, NASA Finder, and direct phone calls (Eastern Kentucky University, n.d.8).

WEAs are one of the fastest means of mass information dissemination ICTs which you often receive as AMBER alerts. Both WEA and TERA rely on Short Messaging Service (SMS) for communication, which can become ineffective during a disaster if there is no reception. Serval project is very innovative and uses current phones to establish communication between two phones without using a network, similar to the iPhone airdrop feature. But, it is still being developed and will require a steep learning curve before being adopted by the general population. A survey conducted by the United Nations in the Caribbean found that several countries do not discuss ICTs in their existing disaster response plans. It also noted that social media has become one of the most powerful forms of communication technology. However, the survey indicated disaster response agencies are not using social media as aggressively and effectively as it can be used (Williams & Phillips, 20149).

Without the knowledge of which technologies to use, individuals may rely on discontinued or unreliable technology, resulting in individuals remaining in their homes when they should have evacuated or not knowing where to evacuate. If public health providers are unable to reach the community, it impacts social determinants of health by impeding access to health care, social life and support, and education. It also impacts access to several disaster recovery resources, such as government aid. This can prevent affected populations from recovering quickly and increase chances of having both physical and mental health conditions (Hall et al., 201810; Allen, 201911). Effective use of ICT can aid in easing the public’s anxiety when dealing with lack of access to various public resources after the disaster (van Westen et al., 202012). ICTs can help disaster aid reach the affected public faster and improve the coordination of disaster recovery efforts. We understand that ICTs are often not very distinct for disaster response and disaster recovery. Hence, this study will focus on answering questions about knowledge, use, and barriers to using ICTs for both disaster recovery and response.

Previous research on the effectiveness and use of ICTs during disasters in small island countries and territories is limited. Moreover, these studies have focused the views of national public health and disaster agencies (Firdhous, 2018; Williams, 2014). Previously, no comprehensive survey or other research project has focused on the effectiveness of ICTs in U.S. territories for disaster response and recovery. Hence, there was a need to study the use and effectiveness characteristics of ICTs in U.S. territories, such as the USVI, which has a small ecosystem and doesn’t have a large-scale response system and resources like the U.S. mainland. Specifically, we study the awareness, use, competency, barriers for using, and effectiveness of ICTs. Findings from this assessment will help us develop policies, interventions, and training programs which can make the community more resilient. Critical factors such as sex, geographic location, type of disaster, age, and level of education were considered for the survey so that we can develop targeted training and intervention methods to better equip all types of people with awareness and competency in ICTs. For this study we focus on some of the most popular forms of ICTs, namely, social media, online services and apps (e.g., FEMA App), Radio, WEAs, and SMS. We also examine whether other technologies apart from those mentioned above are used on the island.

Research Design

Research Questions

The three research questions of this study were:

- What do leaders of public health organizations feel community members should have in terms of awareness about technologies used for disaster response?

- What technological tools do at-risk populations report using and what competencies do they have to use these tools? Are there barriers to using these technologies?

- What disparities exist between at-risk populations’ utilization of disaster-related technological tools and current public health organizations’ technological tools?

Study Site Description

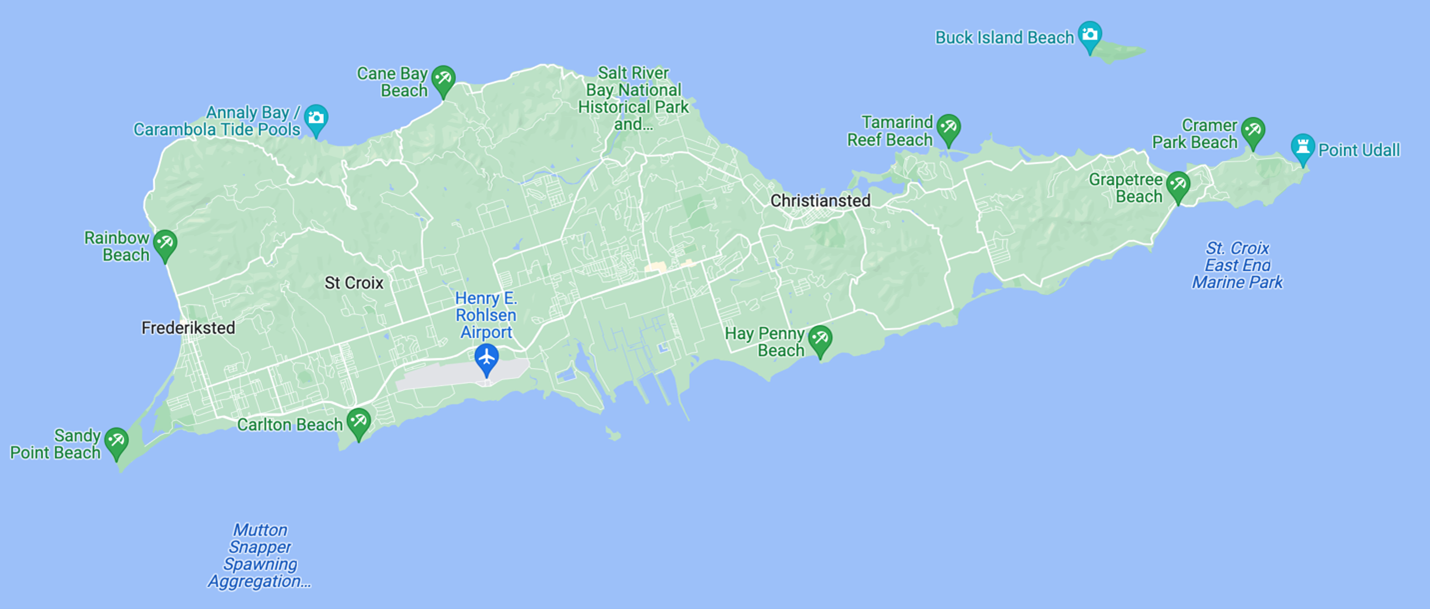

This study was conducted on St. Croix, United States Virgin Islands (USVI). Six low-income housing projects were targeted for the survey, which included three private and three public communities. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (n.d.)13, “public housing was established to provide decent and safe rental housing for eligible low-income families” (para. 1). We consider private housing as rental housing provided by private companies or independent individuals. We chose different types of housing community to include individuals with different income levels. The communities were chosen based on their geographical location on the island. One of the communities is located on the western tip of the island, two of the communities are located mid-island, and three of the communities are located in the eastern part of the island. A map of the USVI St. Croix Island is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Map of St. Croix Island

Image Credit: Google Maps

Image Credit: Google Maps

Data, Methods, and Procedures

Qualitative Methods

Prospective public health leaders were recruited via emails and phone calls. After connecting, an email explaining the study and the informed consent was sent to each leader. Once the informed consent was returned, a Zoom interview was scheduled. With permission from the participant, the interviews were recorded using Otter, a transcribing software. The total length of interviews lasted from 60 to 90 minutes. For a list of qualitative interview questions asked, please refer to Appendix A.

Quantitative Methods

Prospective community participants from select housing communities were notified of the upcoming study via flyers. Before data collection, letters explaining the survey were placed in resident mailboxes or under their doors. The type of delivery was determined by the Housing Office. The letter included a written version of the informed consent, a QR code, the survey link, the contact information for the research team, and the name of a community contact person designated by the researchers. The latter person was the Community Resilience Advocate (CRA). The letter indicated when the QR codes and survey link would be activated and a unique code for them to enter when accessing the survey. This aided in preventing participants from submitting multiple responses. In addition to the activated QR codes, a CRA assisted by going within the neighborhood to recruit participants. They used iPads to allow participants without internet access to complete the survey. COVID-19 protocols were followed throughout the entire study. Before starting the survey, all participants consented to the study by selecting “I consent” or opted out by selecting “I do not consent.” Please see Appendix B for the survey questionnaire.

Low-income individuals often have access barriers, such as limited education, lack of or familiarity with technology, and mobility challenges, to name a few. To address these potential barriers, all communications about the study included a contact number where individuals interested in participating could receive assistance to do so. During the data collection phase, CRAs also visited homes within the community and offered their assistance, if needed, to complete the survey as their proxies. We have followed Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (2018) which recommend using techniques such as creating surveys in more than one language according to the survey population, having alternative texts for images, and using appropriate color schemes and texts to make it more accessible to different demographics and populations.

Data Analysis

This project used a mixed-method design, focusing on answering the three questions discussed earlier. A qualitative analysis of interviews from leaders of public health organizations helped us understand the technologies and methodologies already in place for disaster response in USVI. Subsequently, a quantitative analysis of survey responses from at-risk populations helped us understand the technologies the population is aware of and is comfortable using. Finally, we brought together the results from these analyses in order to develop strategies which can reduce the communication gap between public health agencies and at-risk populations. This mixed-methods design helped us be flexible, gather data efficiently at multiple levels and analyze the holistic view of ICT use and effectiveness in USVI. The detailed research plan is described as follows:

Stage 1. Stage 1 assessed the technologies currently used by public health and community-based organizations and other related governmental agencies during disaster recovery and post-disaster public health restoration activities in USVI. The results were synthesized from semi-structured interviews with leaders and managers of organizations and agencies, as well as public health practitioners, social workers, and other first responders. The purpose of these interviews was to document the technology used by the agency for disseminating information to at-risk populations, getting responses from at-risk populations, collecting critical information during and post disaster, number of participants in the program, effectiveness of technology and areas of improvement. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed using qualitative data analysis tools such as descriptive analysis and data visualization.

Stage 2. We assessed the technologies that at-risk populations need, are aware of, and are comfortable using through surveys of residents in public housing communities. The survey contained Likert style questions and data were quantitatively analyzed using visualization, descriptive and statistical tools to extract useful information about technological needs during disasters in USVI. The data were analyzed for factors such as age, sex, income, and area of living. We also analyzed barriers, such as lack of familiarity with the ICT, lack of knowledge about the ICT, lack of internet or phone access due to the disaster, limited education, physical disabilities, low income status, and lack of information from public health and government agencies. The questions were also tailored to different ICT options chosen by the respondent.

Stage 3. We compared the results from Stage 1 and Stage 2 to find disparities, discrepancies, and gaps between the available ICT that public health agencies can use to assist the community in disaster response and recovery and the technological, informational, and awareness needs of the community. Specifically, we assessed whether at-risk populations are aware and competent in using the technologies used by public health agencies for bi-directional communication or uni-directional dissemination of information. We also assessed whether there is a need for new innovative technologies or communication channels for certain populations. We have analyzed the level and need of competencies to use these technologies among at-risk populations. Data were analyzed using descriptive and statistical techniques to assess differences between populations groups and technology type. T-tests were used for comparing populations. We also determined whether there were linear correlations between competency level of using the technology and participant age and education level. Results from this critical needs assessment will help us identify technological needs and recommend more targeted training for better communication and collaboration between public health agencies and at-risk populations. The results from this study about competency characteristics of at-risk groups towards new disaster response technologies can be generalized to communities in similar U.S. territories and island countries, especially in the Caribbean.

Sampling and Participants

For the in-depth interviewees, several professionals from public health, disaster response and management, and nonprofit community-based organizations were contacted to participate in semi-structured interviews, and many expressed an interest in the study and a willingness to participate. One leader recommended employees within the technology department of that agency who would be appropriate to interview. Unfortunately, neither the agency head nor the suggested employees confirmed their interview, despite many attempts to schedule a date. One of the employees never responded to any communications. To date, two heads of public agencies followed through and completed interviews with the investigators.

The target population for the survey included communities at risk to natural hazards in USVI. These at-risk populations included apartment dwellers, shop owners, boat owners, lower income families, and older adults. These groups that are more vulnerable to natural hazards. Considering the time and financial constraints of the research, we used a convenience, grab and snowball sampling strategy for this study design. The total number of respondents included in the study for analysis was 166. This number depended on availability to participate in the surveys and estimated authentic response rate of surveys. The bias due to grab sampling were reduced using techniques such cross validation and multiple sampling. We partnered with local organizations and community advocates to assist in reaching diverse populations, which made the results more robust and reduced potential bias.

Ethical Considerations, Researcher Positionality, Reciprocity, and Other Considerations

The research team obtained approval from the California State University-Sacramento Institutional Review Board prior to conducting the study. The research team ensured that each member completed their CITI certification and CONVERGE Broader Ethical Considerations for Hazards and Disaster Researchers Training Module. After receiving IRB approval, electronic informed consents that provide participants with an overview of the study and its risks, benefits, and confidentiality statements were provided to every participant. Survey participants had an opportunity to agree to the electronic consent form by clicking “I consent” or they could opt out of the study by clicking “I do not consent.” Interview participants received an email with the consent form and signed and returned the form prior to participating in the interview. All participants had the opportunity to withdraw from the survey at any time. Regarding participant confidentiality, only the research team had access to participant responses and ensured that the data was maintained securely.

Findings

Interview Findings

The interviews were instrumental in informing questions for the quantitative survey. One participant, who works with an organization that assists during disasters and recovery, indicated that the community could be more aware of organizations that have the capacity to assist seniors who live alone or have medical conditions. Additionally, they indicated there are electronic systems for seniors that can send SMS alerts in the event of an emergency, as well as receive requests for assistance. One of the agencies that was highlighted in both interviews was the Virgin Islands Territorial Emergency Management Agency (VITEMA), which has online resources and also provides a platform for residents to register their phone numbers or emails to receive emergency alerts about natural disasters. At the time of the interview, 14,000 individuals signed up for the alerts. One participant highlighted the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration which reestablished weather alerts after Hurricane Maria and stated that it broadcasts 24 hours a day through a weather radio. In addition, a VITEMA Facebook page is currently active, which updates the population about recent activities, resources, and emergency alerts. At the time of writing this report, there were 15,000 followers of the page.

According to Public Health Leader 1, the most powerful of all stated electronic apps is FEMA's Integrated Public Alert Warning System (IPAWS). This application is capable of pushing emergency SMS alerts to any cell which is active on USVI and connected to the cell towers. As these provide only short messages, much of the communication can be an instruction to tune into an emergency radio channel for more detailed alerts. Several government and non-profit agencies are involved in emergency management in USVI, such as fire services, water services, power services, waste management, the department of human services, bureau of information technology, the U.S. National Guard, healthcare services, transportation agencies, the Red Cross, and the department of education. One of the participants indicated that the main challenge agencies face is ensuring that communication is “clear, concise and timely about the messaging sent through emergency radio and SMS.”

Public Health Leader 1 indicated that there is some concern about the challenges of communicating with tourists, as there are a lot of visitors to the island and it is difficult to communicate with them about the disasters early in the event. The main suggestion for the community was to have a radio on at all the times, whether it be a car, handheld, or stand alone radio, since one of the most resilient ways of getting emergency alerts is via emergency radio channels. WEAs through cellphones were the second most used method to send emergency alerts. Another barrier was the fact that each radio station needs to broadcast messages separately; however, there is no central or single channel to communicate to multiple radio stations/other media simultaneously. This makes it harder to broadcast messages in a timely manner.

Public Health Leader 2 stressed that disaster preparedness education is very important and indicated that there are education campaigns on St. Croix for adults, as well as children. During hurricanes and other disasters, the power is frequently disconnected and several communication lines can break. They emphasized the importance of emergency radio. Agencies encourage people to buy emergency radios and also provide radios to senior citizens free of cost or to groups of people who attend the disaster preparedness education workshops. It was also suggested that text messaging was used to communicate instead of mobile phone service, which can be unstable and requires more bandwidth. Immediately after a disaster, if phone lines and power are out, satellite phones are used to communicate (send messages) with different agencies such as the fire department and police department on the island. Emphasis was placed on the need to improve cellular service on the island, which has not been up to par since the 2017 hurricanes.

The participants talked about the Red Cross smartphone application, to which residents can subscribe. Even though the IPAWs service exists, participants stated there is no way of knowing if everyone is getting those texts. It is important to be able to estimate the percentage of population that is being reached via disaster-related technologies, as sometimes post-disaster communication is needed to distribute resources in places that need them, especially at hospitals or healthcare organizations.

Another barrier that was stated is the difficulty residents face when trying to acquire emergency communication equipment, such as radio, satellite phones, or ham radio from stores. According to Public Health Leader 2:

There is not adequate supplies in the stores for these equipment especially during/after the disaster and many stores don’t take orders for these equipment. There should be emphasis on stocking this equipment by buying it online before a disaster happens as a disaster preparedness measure. There are enough communication channels to help in communication during and after the disaster. The focus should be on using them efficiently.

Survey Findings

For the quantitative surveys, 166 surveys were authentic and within the population we wanted to sample in the St. Croix area. We analyzed these 166 online surveys for the following things to check for authenticity of the respondent:

- If the survey was done by a robot or human (more on this issue is included in the Limitations section)

- If the region of St. Croix and the apartment matched

- If multiple surveys were done by the same internet protocol (IP) address

- Geolocation of the IP address

- Total time taken to complete the survey

The characteristics of the 166 survey participants are presented in Table 1. A little more than half of participant were female (52.41%). Most (92.17%) were between 25 to 54 years old. Most of the participants (>98%) were affected by the hurricanes Maria and Irma in the year 2017. Almost three-fourths of the participants completed a bachelor’s or an associate degree. More than three-fourths of the participants were from households with total income between $35,000 and $75,000. Around 90% of participants were from the regions of Frederiksted and Christiansted. For internet access, 88% of the participants indicated having access to the internet at home and 9.64% use only their phone for internet access.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Survey Participants

| Sex | Male | 52.4 |

| Female | 47.59 | |

| Age | 18-24 | 4.82 |

| 25-34 | 35.54 | |

| 35-44 | 37.35 | |

| 45-54 | 0 | |

| 55-64 | 3.01 | |

| Education Level | High School | 2.41 |

| Some College | 19.67 | |

| Associate | 25.3 | |

| Bachelors | 47.59 | |

| Doctorate | 1.2 | |

| Total Household Income | Less than $9,000 | 1.20 |

| $10,000 to $19,999 | 3.61 | |

| $20,000 to $34,999 | 8.43 | |

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 51.81 | |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 25.9 | |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 7.23 | |

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 1.2 | |

| Region of St. Croix | Christiansted | 43.37 |

| Frederiksted | 47.59 | |

| Mid-Island | 9.04 | |

| Housing Community | Community 1 | 34.34 |

| Community 2 | 10.24 | |

| Community 3 | 13.25 | |

| Community 4 | 22.29 | |

| Community 5 | 11.45 | |

| Community 6 | 7.83 | |

| Internet Access | Broadband | 88.55 |

| Only use cell phone for internet | 9.64 | |

| No internet at home, use public wifi | 1.81 | |

Note. N=166.

Of ICTs used during the disaster, smartphone app was mentioned the highest number of times (16.56%), followed by online services and websites (13.9%), social media (13.08%), radio (12.47%), local news channel (12.06%) and SMS (11.04%). The least mentioned channels were the VITEMA app (4.09%) and the FEMA app (7.6%). Of the ICTs used after the disaster for getting resources, smartphone app was mentioned the highest number of times (19.14%), followed by online services and websites (18.14%), SMS (16.32%), social media (16.12%), and radio (11.83%). For the responses about the agencies which were mentioned to be helpful, local fire department was mentioned the most number of times (22.08%), followed by Red Cross (20.8%), local police department (18.52%), VITEMA (15.98%) and FEMA (14.46%).

For the question about familiarity in using ICTs during a disaster, the participants mentioned radio most of the time (19.82%), followed by smartphone apps (14.2%), social media (14.0%), online and web services (13.3%) and SMS (12.64%). Participants were least comfortable with Ham Radio, Satellite radio and television. When asked if they own the ICT, the participants mentioned radio most of the time (19.9%), followed by smartphone app (14.03%), online and web service (12.12%), social media (11.32%).

Participants between the ages of 55 and 64 were most comfortable with SMS and radio. Ages 25 to 54 were most comfortable with radio, however other ICTs were also fairly comfortable. Females responded more comfortably in using social media, smartphone apps and web services than males. Participants with some college as the highest degree were more comfortable with radio and SMS, while participants with bachelor’s degree were more comfortable with social media and smartphone apps.

We intend to do a couple of more interviews and some more in-person quantitative surveys, especially among senior citizens who may not have the expertise to use online resources. We still have more data to analyze, such as barriers for different type of ICTs, which we will published at a later date.

Conclusions

Main Findings

Around 15-20 government agencies and several non-profit organizations provide disaster response and recovery efforts in USVI. The main forms of ICTs being used for inter-agency communication are phone lines, SMS, and online services during normal times. When normal services are broken during and after disasters, ham radios and satellite phone are used to talk between different agencies. The main form of ICT for mass emergency alerts to populations is emergency radio and SMS (IPAWs) during and after a disaster. The population of USVI is estimated to be 106,290 (U.S. Census Bureau, 202114). Other services like smartphone app subscription, and Facebook page cover a maximum of 15% of the total population.

Public Health Implications

Stage 3 of this study, which is still ongoing, will contribute to important public health implications. First, it will provide public health providers with insight into whether a disconnect exists between their recommended pre- and post-disaster technologies and the community’s awareness and usage of those technologies. Specifically, the results of this study can be used to inform leaders of public health organizations on the barriers which prevent at-risk groups from using these technologies. This can help these agencies develop interventions to increase the awareness of and access to technological tools within public housing communities. The results may also lead to the creation of policies or a new app specific to improving communication and information sharing.

Second, the results of the study may also highlight areas for improvement within the community-public health provider relationship. It is the aim of the researchers to create a model for assessing a community’s technological awareness and usage of post-disaster technology while increasing the community’s connection to its public health providers. This model can help to bridge a gap and increase future communication between residents and public health leaders.

Limitations and Strengths

One major limitation of the study, which the researchers did not anticipate, was individuals (or bots) taking the survey who did not meet the criteria, in order to receive the stipend. The researchers did their best to clean the data and remove any responses that were likely fraudulent. In addition, once the issue was noticed, the survey was closed and a new survey was distributed that required participants to enter the code they received from the researchers or a community contact designated by the researchers.

Future Research Directions

While this research highlights technology awareness and use on St. Croix, future studies should examine the other U.S. Virgin Islands (St. Thomas, St. John, and Water Island). The islands that comprise the USVI make up one territory, but their traditions, beliefs, and other ways of life can differ. It would be advantageous to extend the study to include the other islands and analyze whether there is a difference between and among residents on the islands. In addition, safeguards should be in place to reduce the likelihood of individuals taking the survey for financial gain.

References

-

Harrison, C. G. & Williams P. R. (2016). A systems approach to natural disaster resilience. Simulation modelling practice and theory, 65, 11–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simpat.2016.02.008 ↩

-

Vos, M., & Sullivan, H. T. (2014). Community resilience in crises: Technology and social media enablers. Human Technology, 10(2), 61-67. https://doi.org/10.17011/ht/urn.201411203310 ↩

-

Popescu, R., Beraud, H., & Barroca, B. (2020). The impact of hurricane Irma on the metabolism of St. Martin’s Island. Sustainability, 12(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12176731 ↩

-

Ambrose, Wyndi. (2019, September 5). Remnants of Irma and Maria: Two Years Later, Blue Roofs Still Abound. The St. Thomas Source. https://stthomassource.com/content/2019/09/05/remnants-of-maria-two-years-later-blue-roofs-still-abound/ ↩

-

Nieves-Pizarro, Y., Takahashi, B., & Chavez, M. (2019). When Everything Else Fails: Radio Journalism During Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Journalism Practice, 13(7), 799-816. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1567272 ↩

-

Firdhous, M. F. M., & Karuratane, P. M. (2018). A model for enhancing the role of information and communication technologies for improving the resilience of rural communities to disasters. Procedia Engineering, 212, 707-714. ↩

-

Levius, S., Safa, M., & Weeks, K. (2017). Use of information and communication technology to support comprehensive disaster management in the Caribbean countries. Journal of Information Technology Case and Application Research, 19(2), 102-112. ↩

-

Eastern Kentucky University. (n.d). When disaster strikes: Technology’s role in disaster aid relief. https://safetymanagement.eku.edu/blog/when-disaster-strikes-technologys-role-in-disaster-aid-relief/ ↩

-

Williams, R. C., & Phillips, A. (2014). Information and communication technologies for disaster risk management in the Caribbean. United Nations. https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/36735 ↩

-

Hall, C., Rudowitz, R., Artiga, S., & Lyons, B. (2018, September 19). One year after the storms: Recovery and health care in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. KFF/Medicaid. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/one-year-after-the-storms-recovery-and-health-care-in-puerto-rico-and-the-u-s-virgin-islands/ ↩

-

Allen, G. (2019, April 23). After 2 hurricanes, a ‘floodgate’ of mental health issues in U.S. Virgin Islands. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2019/04/23/716089187/after-two-hurricanes-a-floodgate-of-mental-health-issues-in-the-virgin-islands ↩

-

van Westen, C. J., Hazarika, M., & Nashrrullah, S. (2020). ICT for Disaster Risk Management. Academy of ICT Essentials for Government Leaders. Asian and Pacific Training Centre for Information and Communication Technology for Development. https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/ict-for-disaster-risk-management-the-academy-of-ict-essentials-fo ↩

-

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (n.d.) Public housing: What is public housing? Retrieved July 28, 2022, from https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/ph ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2021, April 26). 2020 Census Apportionment Results, Table 2 Resident Population for the 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/data/apportionment/apportionment-2020-table02.pdf ↩

Roy, N. & Clavier, N. (2022). The Use of Disaster Information and Communication Technology Among At-Risk Populations in U.S. Virgin Islands (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 16). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/the-use-of-disaster-information-and-communication-technology-among-at-risk-populations-in-u-s-virgin-islands