Exploring the Mental Health Impact of Hurricane Beryl on Racial Minorities in Houston, Texas

Publication Date: 2025

Abstract

In July 2024, Hurricane Beryl caused widespread devastation across multiple regions before making landfall in Houston where it disproportionately impacted socially vulnerable communities. The storm’s destruction disrupted infrastructure, displaced thousands, and strained emergency response systems, exposing critical gaps in access to essential services, mental health support, and disaster recovery resources. Using surveys (N=118 respondents) and focus groups (N=34 participants), this study examined the traumatic experiences and primary stressors reported by racial minorities, the barriers that they experienced in accessing mental health and other essential services and resources, and the coping mechanisms they employed. Results indicate that 61.0% of participants experienced the loss of energy, water, or food. Additionally, 70.3% of respondents faced difficulties in accessing food due to transportation, financial, or logistical constraints. Furthermore, 44.9% reported being unable to obtain necessary health care, citing service unavailability, eligibility restrictions, and lack of awareness of disaster-related health care services. Awareness of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) crisis counseling services was relatively low, with only 22.0% of respondents indicating they were aware of the resource, while 72.0% reported they were not aware. Among all respondents, only 6.8% reported utilizing the service. Coping strategies varied, with 39.1% of respondents describing emotional and practical responses, including reliance on social networks, spiritual resilience, and lessons in disaster preparedness. Focus group discussions revealed frustration over bureaucratic hurdles in accessing financial and mental health support, exacerbating emotional distress. The results of this study highlight the need for improved communication, targeted outreach, and streamlined access to mental health services, particularly in underserved communities that are disproportionately affected by disasters.

Introduction

On July 8, 2024, Hurricane Beryl made landfall near Matagorda, Texas, significantly impacting Southeast Texas with widespread flooding and wind damage. As one of the strongest storms to hit the region in recent history, it caused widespread power outages and major disruptions to essential services. Authorities at various levels recommended evacuations, with counties like Matagorda, Nueces, and Refugio among those that issued mandatory evacuation orders for residents. However, transportation-disadvantaged populations—including low-income individuals, carless households, the elderly, and racial minorities—faced significant challenges in reaching safety. Additionally, limited access to healthcare facilities and food sources further exacerbated the struggles of these communities, making it difficult to obtain necessary resources in the aftermath of the storm.

This study employed a mixed-methods research design to examine the mental health impact of Hurricane Beryl on minorities in Houston, focusing on the Third and Fifth Wards—two historically underrepresented and underserved neighborhoods that have long been affected by disasters and environmental injustice. We collected data through surveys (n=118) and focus groups (Third Ward: n=9 participants; Fifth Ward: n=25 participants) to explore the traumatic experiences and primary stressors following the hurricane. Additionally, the study identified key barriers to accessing mental health services and resources, as well as the coping mechanisms employed. Specifically, this study analyzed the intersection of disaster exposure, systemic inequities, and mental health challenges in these communities. The findings provide insight into gaps in disaster response efforts and offer recommendations for more inclusive recovery strategies that prioritize the well-being of vulnerable populations.

Literature Review

Natural hazards, such as hurricanes, can have extreme and lasting effects on mental health, particularly among historically marginalized communities. Early research established that the psychological toll of such events includes post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression and other stress-related disorders, often exacerbated by pre-existing socioeconomic disparities (Rivera et al., 20221). Over time, scholars have increasingly highlighted how minority populations face disproportionate disaster impacts due to systemic inequities in housing, healthcare access, and social support systems (Smith et al., 20222). Studies from major hurricane events such as Katrina and Harvey reinforced these findings, demonstrating that Black and Hispanic residents were significantly more likely to experience PTSD and depression compared to their White counterparts (Olonilua, 20233). These disparities remain linked to structural factors, including financial constraints, lower rates of access to mental health services, and institutional distrust (Olonilua, 2023). Additionally, the compounded effects of discrimination, social marginalization, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure further exacerbate mental health challenges in these communities (Flores et al., 20244).

Hurricane Beryl’s impact on Houston’s minority communities is expected to mirror these trends, particularly in neighborhoods like the Third and Fifth Wards, which have long suffered from environmental injustice and inadequate disaster recovery efforts which continue to persist. Research indicates that minority populations are more likely to reside in flood-prone areas and face greater difficulties in accessing disaster relief resources, leading to prolonged recovery periods and heightened mental health burdens (Njoku & Sampson, 20235). These vulnerabilities are further intensified by intersecting factors such as economic instability, housing insecurity, and preexisting health conditions (Olonilua, 2023). Access to mental health services is critical for disaster recovery, yet minority communities often encounter significant barriers. Structural obstacles such as financial constraints, lack of insurance coverage, and provider shortages in minority-dense neighborhoods hinder timely psychological support (Ferreira et al., 20246). Cultural and linguistic factors also influence mental health-seeking behaviors, with studies indicating that stigma surrounding mental illness is more prevalent in minority communities, discouraging individuals from seeking help (Rivera et al., 20247).

In sum, while significant research establishes the mental health impacts of hurricanes, particularly in marginalized communities, our understanding of how these effects have manifested in the wake of Hurricane Beryl remains limited. Specifically, we lack knowledge of the extent to which compounding factors such as socioeconomic disparities, housing insecurity, and limited access to mental health services act as barriers to recovery in communities like the Third and Fifth Wards. Additionally, there is a gap in understanding how intersecting vulnerabilities influence help-seeking behaviors and whether the support provided by public and private entities adequately addresses the unique needs of these populations. Hurricane Beryl provides a unique opportunity to address these research gaps by examining how these systemic inequities and barriers shape mental health outcomes and disaster recovery in real-time.

Research Questions

This report addressed the following research questions:

- What traumatic experiences and primary stressors did minorities experience following Hurricane Beryl?

- What were the primary barriers faced by minorities in Houston when accessing mental health services and resources following Hurricane Beryl?

- What coping mechanisms and mental health services were used or could be used to address the unique needs of minorities affected by Hurricane Beryl?

Research Design

To address these research questions, we used a mixed-methods approach. This approach integrated quantitative surveys with qualitative focus group discussions. The surveys offered a broad overview of the traumatic experiences, barriers to accessing mental health services, and coping strategies. In contrast, the focus groups enabled participants to describe in-depth their lived experiences and emotional responses.

Study Site and Access

Our study focused on surveying and interviewing residents from the areas of Houston, Texas, impacted by Hurricane Beryl. Specifically, the study areas included the Third Ward and Fifth Ward neighborhoods, known for their high population densities and significant socioeconomic challenges. A large portion of the population is composed of minorities, many of whom experience barriers to accessing mental health services. Moreover, these areas are economically disadvantaged, with notable percentages of the population living in poverty and experiencing unemployment (Fawkes, 20228). Many residents also face challenges related to transportation access, as the region has limited public transportation options, making it difficult for those without cars or with mobility limitations to access resources or evacuate when necessary. Local news outlets reported that some residents in the affected areas faced difficulties in reaching medical facilities, even though the city deployed emergency services to provide support (Santini et al., 20249). The area’s healthcare system, already under strain, was further challenged by the storm’s aftermath, as the need for mental health services surged, but resources remained limited (Kraft et al., 202510). The study was built on strong relationships with local community organizations—including the Houston Climate Movement, New Liberty Road Community Development Corporation, and the Community Care Cooperative—that we had forged during previous research projects. These relationships helped us engage effectively with the community and address the unique needs of residents in these underserved areas. These partnerships were also vital in ensuring that our findings were relevant and that the study was conducted in a way that respected the community’s history and concerns.

Survey

Survey Measures

The survey was organized into three main sections. The first part of the survey focused on the traumatic experiences and stressors resulting from the hurricane. Participants were asked to report on the specific challenges they faced, including property damage, displacement, loss of loved ones, and other emotional and psychological impacts. This section aimed to identify the types and extent of trauma experienced by residents. The second section examined participants’ experiences with accessing mental health services following the hurricane. Questions in this section assessed awareness of available resources, the ease or difficulty of accessing these services, and any barriers encountered, such as lack of transportation, insufficient services, or cultural factors that might have hindered help-seeking behavior. The third part of the survey explored the coping mechanisms employed by residents to deal with the aftermath of the hurricane. Participants were asked about both formal coping strategies (such as therapy or counseling) and informal strategies (such as relying on family support or community networks). This section aimed to understand how individuals managed the psychological challenges. The survey also collected demographic information, including age, gender, ethnicity, income, education, and housing status. This section was designed to provide context for the responses and to explore any socio-demographic factors that might influence the mental health impact of the disaster. The full survey instrument is available as Appendix A.

Sampling and Participants

The survey targeted residents of the Third and Fifth Wards of Houston, Texas, who were directly impacted by Hurricane Beryl. We selected these neighborhoods due to their history of vulnerability to environmental disasters, socioeconomic challenges, and significant minority populations. A purposive sampling method was used to ensure that the survey participants reflected the demographics of the target communities. To recruit participants, we posted several times on the Houston Climate Movement Facebook page, LinkedIn, as well as the Principal Investigators’ own Facebook and LinkedIn pages. We also distributed flyers to promote the survey at high-traffic areas within the Third and Fifth Wards. The flyer we used to recruit survey participants is included in Appendix B. Additionally, we attended several community events, including dinners and lunches, to connect directly with residents and encourage participation. The survey was made available in both electronic and physical formats. It was hosted on Google Forms to ensure easy access for those with internet availability, and it was also distributed in paper form for those who preferred to respond offline. We also attended virtual meetings, including the Third Ward Super neighborhood meetings, where we engaged with residents and encouraged them to complete the survey. These outreach efforts led to a total of 118 responses from residents. The combination of digital and in-person recruitment strategies allowed us to reach a diverse group of participants, capturing a wide range of experiences and perspectives.

Survey Data Analysis

For the quantitative portion of the survey, responses were coded and entered into SPSS (Version 29.0.1) for analysis. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, percentages, and measures of central tendency (mean), were used to summarize the data and identify common trends and patterns across the questions. For the open-ended questions on the survey, we coded the responses thematically to identify key themes and patterns in participants’ descriptions of their mental health experiences, barriers to accessing services, and coping mechanisms. We used a grounded theory approach to allow themes to emerge directly from the data rather than being predefined (Khan, 201411). Each response was read multiple times to ensure that all relevant data were captured and categorized appropriately. Key themes were identified and grouped into broader categories, such as “barriers to care,” “sources of stress,” and “effective coping strategies.” We used quotes to provide rich, contextual examples of the themes, while maintaining participant anonymity by assigning pseudonyms. To enhance the validity and reliability of the survey data, we ensured that the questions were clear, concise and unbiased. Additionally, during the data analysis process, we cross-checked responses and conducted inter-rater reliability checks for the qualitative coding to ensure consistency and accuracy in the identification of themes.

Focus Groups

Focus Group Moderators, Participant Recruitment, and Other Procedures

We conducted two focus groups in Houston’s Third and Fifth Wards. The Third Ward group included nine participants, while the Fifth Ward group had 25 participants. Given community concerns that participants might act differently with the Principal Investigator in the room, we arranged for trusted community members to facilitate the focus group discussions. The moderators had relationships with the residents and were trusted to lead the conversations in culturally sensitive ways. Prior to the focus groups, we conducted three virtual training sessions with the moderators to ensure they were well-prepared to guide the discussion and ask the key questions. This approach helped to create a more open, relaxed environment for participants to share their thoughts and experiences.

Participants for the focus groups were recruited through multiple outreach methods, including posts on community and professional social media platforms such as the Houston Climate Movement page and the investigators’ personal LinkedIn and Facebook accounts. Flyers were also distributed in busy neighborhood locations across the Third and Fifth Wards. In addition, we attended local gatherings and community meals to engage with residents in person and invite them to take part. The recruitment flyer we used for the Third Ward is available in Appendix C.

The focus group sessions lasted between 20 to 30 minutes, allowing participants to share their experiences and discuss their challenges in a supportive environment. These focus group sessions were recorded and transcribed by the investigators for qualitative analysis, ensuring that key themes and insights could be systematically identified and examined. At the end of each focus group, participants received a comprehensive resource book, which included a chart showing the government or independent regulatory agency responsible for climate and environmental issues, along with a “Thank you” card that included a $50 cash appreciation gift.

Focus Group Data Analysis

The research team used NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version 12 Plus) to analyze the focus group transcripts through thematic analysis (Ebekozien et al., 202312). We applied both inductive and deductive coding strategies (Bingham & Witkowsky, 202113). Deductive codes were developed based on the research questions and anticipated participant responses, helping to categorize key themes. Inductive coding was also used to identify emergent themes not anticipated during data collection. The data was coded into descriptive or topical themes (Rodriguez & Storer, 202014), with descriptive coding focusing on specific content discussed and topical coding identifying broader patterns. This combined approach provided a thorough understanding of how residents from the Third and Fifth Wards coped with mental health challenges, accessed support, and developed coping mechanisms in the aftermath of Hurricane Beryl.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

The research team submitted the study protocol and survey instruments to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Texas Southern University, Houston, which approved the study in December 2024. We followed ethical guidelines by obtaining informed consent from all participants before they began the survey or focus group. Participants were informed that they could withdraw at any time without penalty. As stated above, focus group participants were compensated with $50 in recognition of their time and contributions,. We also gave a $10 gift to survey participants to compensate them for their time. To protect participant privacy, all data were anonymized and stored on password-protected computers. Findings are reported in aggregate form, and we plan to share key insights and recommendations with community partners such as the Houston Community Movement. We will also share our findings in their newsletter and at local events. Additionally, we already have an interview scheduled with a local newspaper. The research team maintained reflexivity throughout the study to minimize potential biases. Our team has extensive knowledge of the Third and Fifth Wards through partnerships with the Houston Climate Movement and other local organizations. These relationships enabled us to engage with the community effectively and ensure that the study reflected the unique experiences and concerns of residents.

Findings

Background Characteristics of Respondents

The survey respondents ranged in age, with the largest group being between 35 to 44 years (24.6%), followed by those aged 25 to 34 years (21.2%) and 55 years and above (21.2%). A small percentage preferred not to disclose their age (0.8%). The majority of participants identified as African American/Black (85.6%), with a few participants identifying as Hispanic/Latino (3.4%), Native American (3.4%), or other mixed identities. The majority of participants identified as female (57.6%), while 36.4% identified as male. Additionally, 2.5% identified as non-binary/third gender, 1.7% identified as genderqueer/genderfluid, and 1.7% did not respond to the question. Regarding disability, 23.7% of respondents identified as persons with disabilities, with the majority of participants not disclosing or indicating “Not Applicable” (83.9%). Those who did specify their disabilities mentioned a range of physical, mental health, and sensory conditions. Marital status varied, with a significant portion identifying as single (50.8%), while others were married (22.9%), divorced (6.8%), or in other relationship statuses like common law or separated. Housing status showed that most participants rented their homes (62.7%), while 16.9% owned their homes. A smaller percentage lived with family or friends (13.6%) or had other housing arrangements. The predominant language spoken at home was English (87.3%), although some participants spoke both English and Spanish (3.4%). Lastly, the education levels of participants were diverse, with 22.9% holding a high school diploma or equivalent, 27.1% having some college education, and 19.5% holding a bachelor’s degree. Additionally, 6.8% had a master’s degree, 1.7% held a doctoral degree, and 3.4% had a professional degree. Given that the vast majority of respondents identified as African American/Black, this study provides important insights into how Black communities, who often face disproportionate risks during disasters, were affected by Hurricane Beryl.

Traumatic Experiences and Primary Stressors

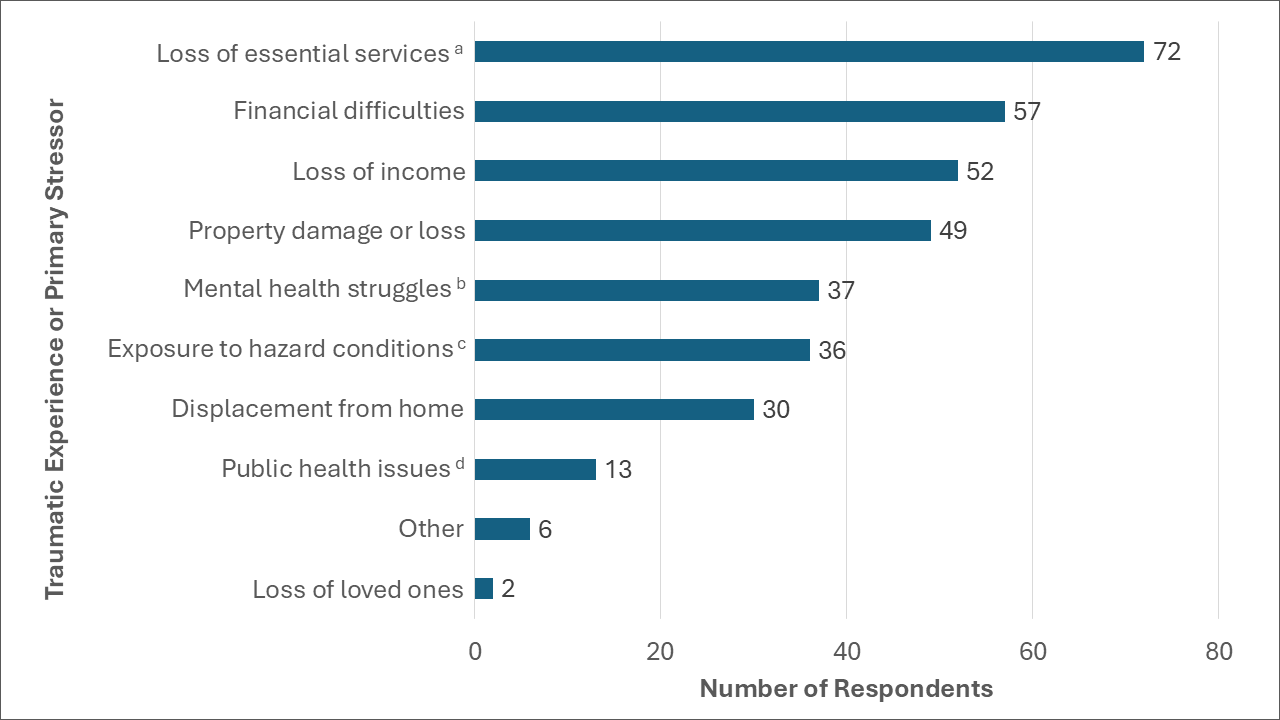

The survey question “Did you experience any of the following traumatic events after Hurricane Beryl?” allowed respondents to select multiple traumatic events they experienced. Figure 1 displays the results. Among the traumatic events listed, the event respondents experienced most frequently (reported by 72 respondents, representing 61.0% of the participants) was the loss of essential services, such as energy, water, or food.. This was closely followed by financial difficulties, which affected 57 respondents (48.3%), and loss of income, which was experienced by 52 respondents (44.1%). These figures demonstrate the significant economic hardship many faced in the aftermath of the hurricane. Additionally, property damage or loss was reported by 49 respondents (41.5%), indicating widespread physical damage to homes and personal property. Mental health struggles, including anxiety and depression, were reported by 37 respondents (31.4%), suggesting that psychological impacts were a major concern for many. Furthermore, displacement from home was experienced by 30 respondents (25.4%), showing that many individuals were forced to leave their homes due to the storm’s devastation. Regarding the perceived severity of traumatic experiences, 38% of respondents reported their experiences as “Very severe” (29.7%), “Extremely severe” (6.8%), or a combination of both (1.7%). Given that the majority of participants identified as African American/Black, these stressors highlight the heightened vulnerability of minority communities, who often face compounding structural barriers during disaster recovery.

Figure 1. Respondent Distribution of Traumatic Experiences and Primary Stressors

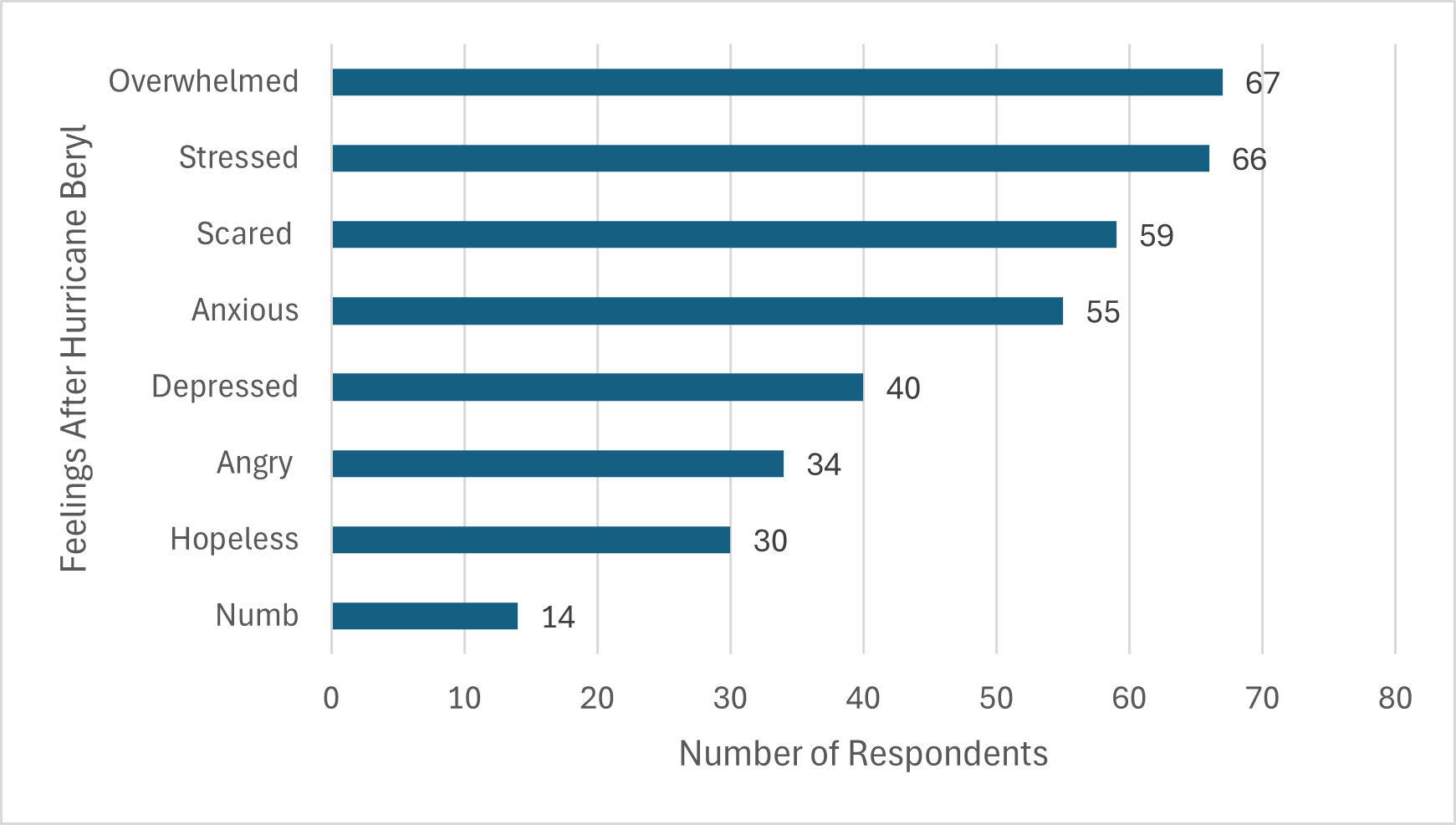

Figure 2 reveals the emotional respondents experienced following Hurricane Beryl. Notably, “overwhelmed” and “stressed” were the most prevalent feelings, reported by 67 and 66 individuals, respectively, highlighting the impact of the event. A substantial portion also reported feeling “scared” (59), “anxious” (55) and “depressed” (40), indicating widespread mental distress. Further contributing to the negative sentiment, 34 respondents felt “angry,” and 30 felt “hopeless.” “Numb” was the least reported feeling, with 14 respondents, though still indicative of the emotional disruption caused by the hurricane. A significant majority (91.5%) experienced energy loss, with over half (53.4%) having to evacuate to restore power. The aftermath also led to significant food disposal, with 89.8% of respondents reporting having to throw away food due to the hurricane’s impact. These findings emphasize the severe disruption caused by the storm, particularly in terms of essential services and daily living conditions.

Figure 2. Feelings Experienced by Respondents After Hurricane Beryl

Findings from the focus groups were consistent with the survey responses, highlighting the intense fear and uncertainty experienced by many respondents during and after Hurricane Beryl. One participant stated:

When Harvey hit, I was more afraid then than now because, after having already experienced a hurricane before, I knew what could happen. I had seen the destruction firsthand and felt the panic of not knowing if I was going to make it through. The uncertainty of whether the roof would hold, if the water would rise high enough to flood my home, and if help would reach us in time made it all the more frightening. This time, I was more prepared mentally, but the fear from that past experience still lingers. The hardest part is not knowing how much worse it could get, but now, having lived through it once, I feel a little more ready to handle the situation.

Another participant shared:

I felt completely overwhelmed. Not knowing when things would return to normal or if the house would even still be there the next day, it was like living on the edge. The constant uncertainty was exhausting. I kept thinking, ‘Is today the day everything changes?’ The stress of not knowing how long we would be without power, food, or basic services added to that feeling of helplessness. It was mentally and emotionally draining, not just for me, but for everyone around me. It felt like we were all just waiting for the next wave of destruction to hit, and it took a toll on my peace of mind.

These personal accounts further underscore the emotional and psychological strain caused by the hurricane, as participants described living in a state of constant fear, uncertainty, and anxiety, which impacted their overall well-being during and after the event.

Barriers to Accessing Essential Goods and Services

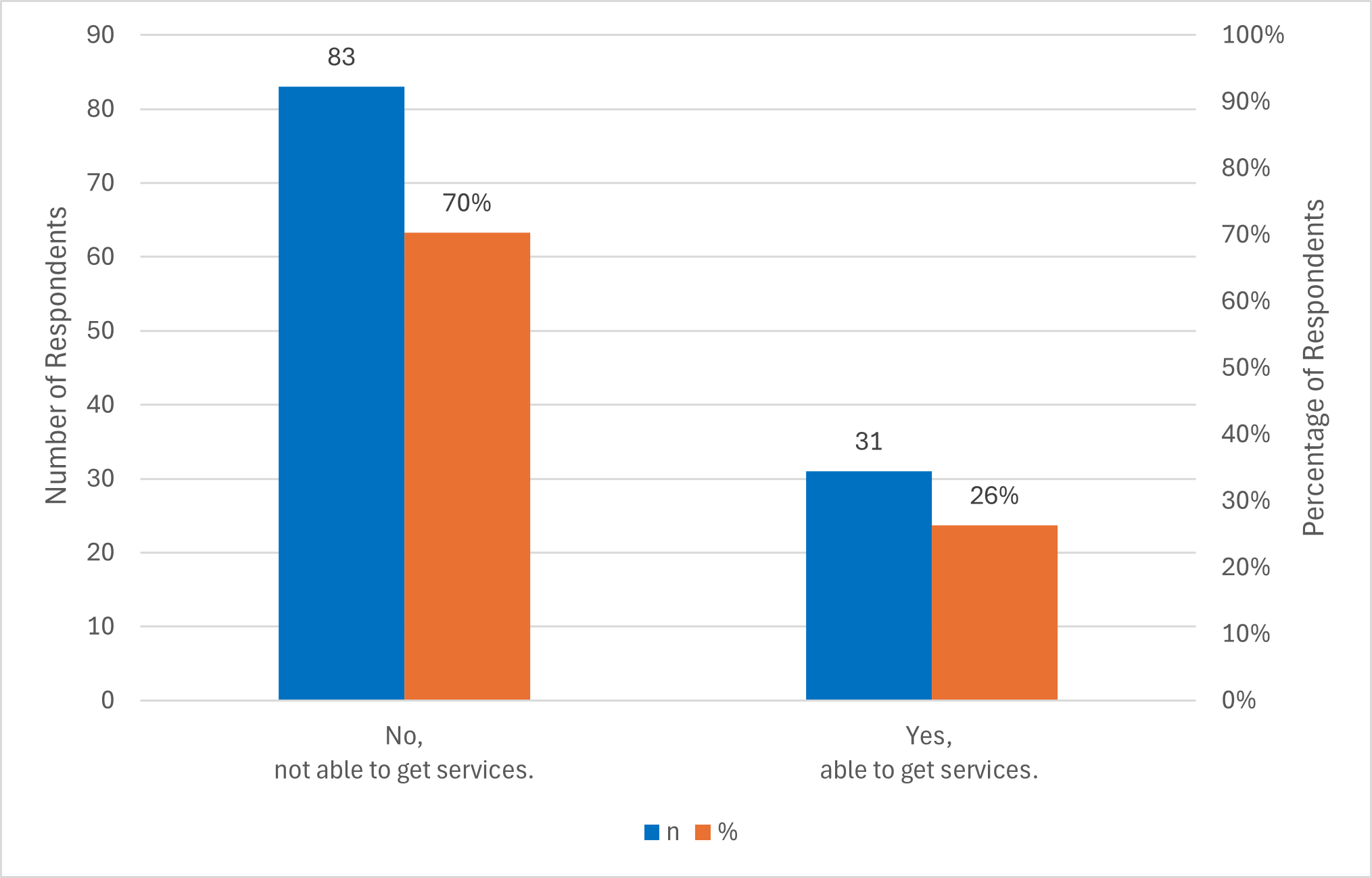

A major barrier identified was difficulty in accessing neighborhood grocery stores. As shown in Figure 3, of the 118 respondents, 83 (70.3%) reported being unable to get to a grocery store whereas only 26.3% reported being able to do so.. This suggests that respondents were experiencing logistical and economic barriers—such as lack of transportation, financial constraints, or physical accessibility issues—that significantly limited their access to basic necessities.

Figure 3. Respondents’ Ability to Get Essential Services After Hurricane Beryl

Another significant barrier respondents experienced was the inability to obtain needed healthcare. Nearly 44.9% of respondents reported that they could not access formal health-related services such as medication, medical care (including emergency room visits), and therapy. Only 26.3% of respondents were able to secure those services, while 22.9% did not respond and 5.9% stated the question was not applicable.

Barriers to Accessing Mental Health Services

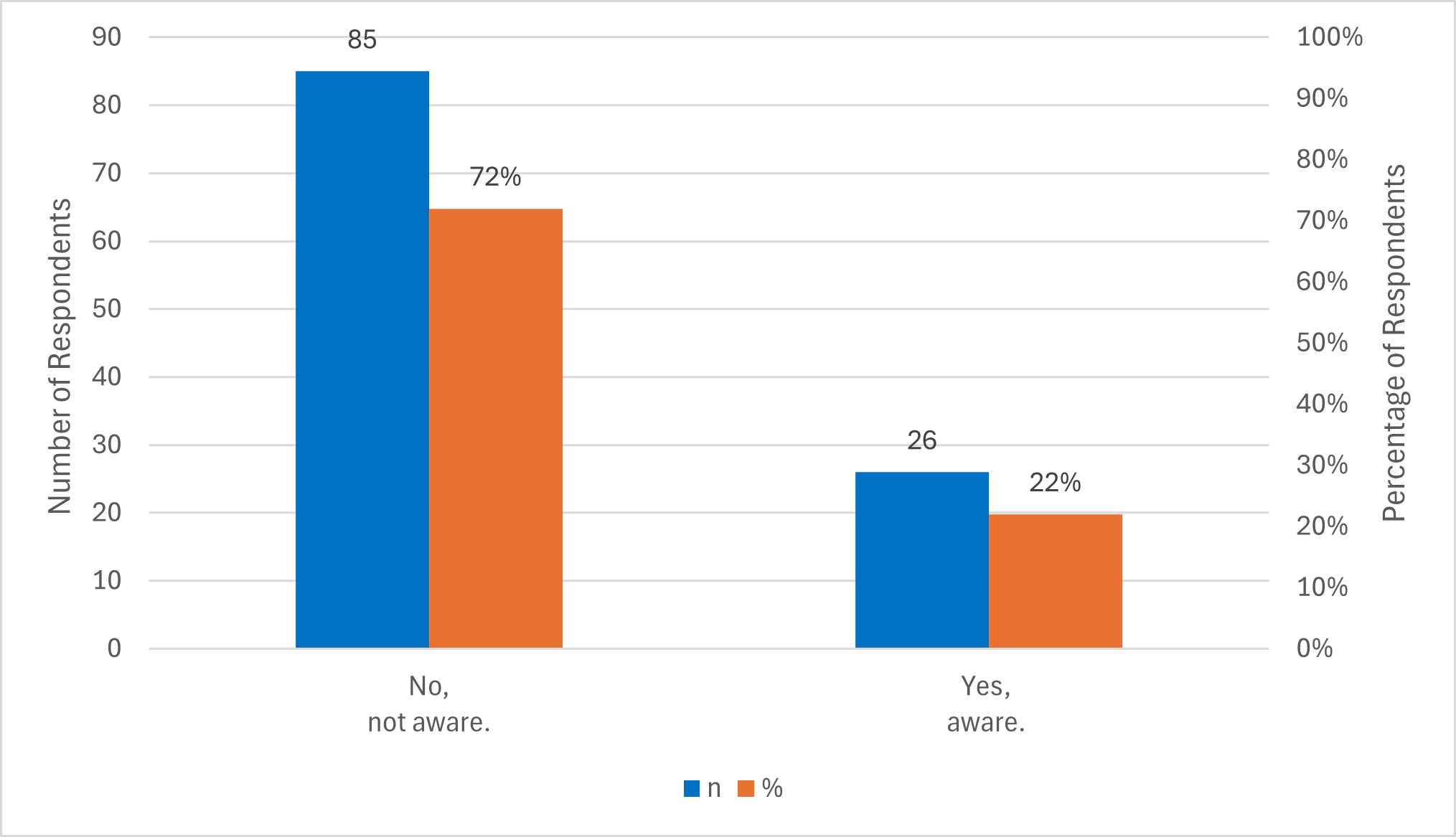

These findings suggest that even when support systems are in place, significant structural barriers prevent effective access. A key obstacle in accessing mental health support was the low level of awareness about the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) crisis counseling services as shown in Figure 4. A large majority (72.0%) of respondents reported being unaware of the service, indicating a communication and outreach gap. This lack of awareness represents a missed opportunity to connect individuals with mental health support.

Figure 4. Respondents’ Awareness of Crisis Counseling Services Provided by FEMA

Even among respondents who were aware of FEMA’s services, utilization was limited. Only 6.8% of respondents reported using the service, while 30.5% stated that they were aware of it but did not use it. A significant proportion (60.2%) did not respond to the question, and 2.5% reported that it was not applicable. This suggests that barriers such as stigma, logistical difficulties, and perceived ineffectiveness may discourage the use of available mental health resources.

The focus group discussion also revealed deep frustration and emotional exhaustion among respondents regarding the process of accessing support and resources after the disaster. Participants expressed feeling abandoned and overwhelmed by bureaucratic hurdles, particularly when dealing with insurance claims and financial assistance. One participant said:

It felt like an unending trauma, as if it was never going to end. You pay for insurance all your life, only file one or two claims in 37 years, and then nature takes away everything. When it is time to get help and fix things, they expect it to come from my pocket first before they reimburse me—but I don’t have a ton of money.

Another participant voiced similar frustration, stating:

I did not even know where to start. There were so many forms to fill out and every time I thought I was making progress; I would hit another roadblock. I was already struggling emotionally and dealing with all the paperwork just made it worse.

This reflects how administrative complexity and lack of clear guidance further compounded the emotional toll of the disaster, creating barriers to both financial recovery and mental health support. The overall sentiment suggests that even when resources are available, the process of accessing them is often so overwhelming that it discourages people from seeking the help they need.

Coping Mechanisms and Mental Health Services for Those Affected

We asked respondents how they coped with the impact of Hurricane Beryl. Notably, 57.6% provided no response, and 3.3% marked the question as not applicable, leaving 39.1% who described specific coping mechanisms. Individual responses—each representing between 0.8% and 2.5% of the total—detailed emotional reactions such as crying, fear, anxiety, and stress, as well as practical responses like sleeping, praying, or managing the challenges of power outages and job loss. One respondent even reported developing symptoms consistent with PTSD. Several respondents reflected on their experiences and the lessons they learned. One participant shared:

I looked at the negatives and found positives in them. In our communities, disasters bring out the best in people. Through this, I saw how it brought together nieces, friends, and distant relatives. We sat down and ate together. In that moment, it showed that we can come together and be positive toward one another.

Another respondent highlighted the importance of support systems and adaptability:

I have been blessed and thankful to have people around me and good people who I know who have been there for me. Their support kept me grounded during such a difficult time. But when disaster strikes, sometimes you do not have a choice—you just have to act. If your family says get up and move, you have to move. There is no time to hesitate because safety comes first. It made me realize how important it is to have a plan and people you can rely on in moments like these.

The need for contingency planning was also emphasized:

Sometimes we have plans, and sometimes you need a backup plan for a plan. You think you are prepared until something unexpected happens and then you realize how quickly things can change. This experience taught me the importance of always having an alternative—whether it is extra supplies, an evacuation route, or even just knowing who to call for help. Being flexible and ready to adapt can make all the difference in times of crisis.

One respondent acknowledged how the hurricane changed their perspective on preparedness:

It made me really think about what I have prepared—do I have all my medications, do I have enough money set aside, do I have an emergency plan in place? Before, I did not talk about stuff like that or even consider how quickly things could change. This hurricane made me see that I was not as prepared as I thought I was. It was a wake-up call to take emergency preparedness seriously—not just for myself, but for my family too. Now, I know I need to plan ahead, stock up on essentials, and be ready for whatever comes next.

These reflections highlight the varying ways individuals coped with the disaster, ranging from emotional and spiritual resilience to practical preparedness and reliance on community support. While some found comfort in their faith and family connections, others focused on taking practical steps to ensure their safety and well-being, such as revisiting emergency plans and organizing resources. The experience also underscored the importance of being adaptable in the face of uncertainty and recognizing the value of strong social networks. Overall, these responses reveal a blend of personal resilience, shared solidarity, and the recognition that effective disaster preparedness requires both emotional and practical readiness.

Conclusions

Implications for Policy and Practice

Overall, respondents’ coping mechanisms during Hurricane Beryl largely reflected themes observed in prior disaster response studies, where emotional and practical responses played significant roles. However, in contrast to previous studies that primarily linked disaster coping to emotional responses or immediate physical needs, this study found that prior experiences had the most significant influence on coping behaviors. This suggests that respondents may have relied on learned coping strategies from past events, and those in areas less frequently impacted by hurricanes—such as the Third and Fifth Wards—may have felt uncertain or ill-prepared. This underlines the need for improved disaster preparedness programs and community-based education on coping with hurricane impacts.

One notable theme from responses was the importance of community connections, as many respondents cited the role of family and neighbors in providing both emotional comfort and practical assistance. However, challenges such as lack of access to mental health services, especially the low awareness of FEMA’s crisis counseling services, could have hindered some individuals’ ability to effectively cope after Hurricane Beryl. A significant proportion of respondents reported being unaware of FEMA’s services, representing a clear communication gap that prevented many from accessing essential mental health support. This highlights the critical need for better outreach and awareness about available mental health resources, particularly for individuals in more isolated or infrequently impacted areas like the Third and Fifth Wards. Given that most respondents identified as African American, these gaps in communication and support point to longstanding disparities in emergency response systems that must be addressed through culturally responsive and community-driven outreach efforts.

These findings suggest that there is a need for better communication and resource allocation, particularly for vulnerable groups in less hurricane-prone areas. Improved mental health services, especially those tailored to post-disaster recovery, would be beneficial for communities that face long-term emotional impacts after a disaster. Targeted interventions that prioritize minority communities, especially in neighborhoods like the Third and Fifth Wards, should be embedded into future disaster response frameworks. Additionally, the study emphasizes the importance of strengthening social networks and support systems—a foundation for emotional resilience and the effective processing of disaster impacts.

Limitations

The sample size may not be fully representative of the broader population, particularly in areas less frequently impacted by hurricanes. This could introduce sampling bias, as those who responded may have had specific experiences or higher levels of engagement with recovery efforts, which might not be reflective of the general population. The study also found that a significant portion of respondents were unaware of FEMA’s crisis counseling services. This highlights a communication gap but also reflects the study’s limitation in measuring the effectiveness or reach of these services in the affected areas. The lack of detailed information about barriers to access—such as logistical challenges, stigma, or perceived service inefficacy—leaves room for further exploration into the reasons behind low service utilization.

Future Research Directions

Future studies could explore the long-term mental health impacts of hurricanes, particularly on vulnerable populations in areas that are less frequently impacted, like the Third and Fifth Wards. Understanding how individuals’ coping mechanisms evolve over time could help in developing more effective mental health support systems that address both immediate and prolonged psychological effects. Also, there is a need for more research on the effectiveness of mental health services, particularly crisis counseling programs, in helping communities recover after a disaster. Future research could examine how barriers can be mitigated to improve service delivery in future disaster response. Also, further research could examine the relationship between prior disaster experience and coping behavior. By analyzing how individuals who have lived through previous hurricanes respond differently to new disasters, researchers could identify specific lessons that could inform future preparedness and resilience-building strategies, particularly in hurricane-prone areas.

References

-

Rivera, D. Z., Jenkins, B., & Randolph, R. (2022). Procedural vulnerability and its effects on equitable post-disaster recovery in low-income communities. Journal of the American Planning Association, 88(2), 220-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2021.1929417 ↩

-

Smith, G. S., Anjum, E., Francis, C., Deanes, L., & Acey, C. (2022). Climate change, environmental disasters, and health inequities: the underlying role of structural inequalities. Current Environmental Health Reports, 9(1), 80-89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-022-00336-w ↩

-

Olonilua, O. (2023). Reducing risk through public engagement in hazard mitigation plans. In H. Grover, T. Islam, J. Slick, & J. Kushma (Eds.), Case studies in disaster mitigation and prevention (pp. 45-60). Butterworth-Heinemann. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809528-7.00005-8 ↩

-

Flores, A. B., Sullivan, J. A., Yu, Y., & Friedrich, H. K. (2024). Health disparities in the aftermath of flood events: a review of physical and mental health outcomes with methodological considerations in the USA. Current Environmental Health Reports, 11(2), 238-254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-024-00446-7 ↩

-

Njoku, A. U., & Sampson, N. R. (2023). Environment injustice and public health. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of social sciences and global public health (pp. 1987-2006). Cham Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25110-8_37 ↩

-

Ferreira, R., Davidson, T., Buttell, F., Contillo, C. M., Leddie, C., Leahy, C., ... & Friedman, R. (2024). Barriers to equitable disaster recovery: A scoping literature review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Article 104628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104628 ↩

-

Rivera, F. I., Belligoni, S., Arroyo Rodriguez, V., Chapdelaine, S., Nannuri, V., & Steen Burgos, A. (2024). Compound crises: The impact of emergencies and disasters on mental health services in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(10), Article 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101273 ↩

-

Fawkes, L. S. (2022). Residential creosote exposure: An assessment of community health and environmental health risks in the Greater Fifth Ward, Houston, Texas [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Texas A&M University. https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/198037 ↩

-

Santini, M., Armas, F., Carioli, A., Ceccato, P., Coecke, S., De Girolamo, L., Duta, A.-M., Gawlik, B., Giustolisi, L., Kalas, M., Maddalon, A., Marí Rivero, I., Marzi, S., Masante, D., Mastronunzio, M., Moalli, D., Panzarella, G., Poljansek, K., Proietti, C., Salvitti, V., & Voukouvalas, E. (2024). Hurricane Beryl: JRC emergency report. European Commission Joint Research Centre. https://civil-protection-knowledge-network.europa.eu/system/files/2024-12/hurricane-beryl-report.pdf ↩

-

Kraft, L. L., Villarini, G., Czajkowski, J., Zimmerman, D., & Amorim, R. S. (2025). Developing a spatial regression model framework for insured flood losses in Houston. ASCE OPEN: Multidisciplinary Journal of Civil Engineering, 3(1), Article 04025002. https://doi.org/10.1061/AOMJAH.AOENG-0044 ↩

-

Khan, S. N. (2014). Qualitative research method: Grounded theory. International journal of business and management, 9(11), 224-233. ↩

-

Ebekozien, A., Aigbavboa, C., & Aliu, J. (2023). Built environment academics for 21st-century world of teaching: stakeholders' perspective. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, 41(6), 119-138. Vol. 41 No. 6, pp. 119-138. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBPA-04-2022-0062 ↩

-

Bingham, A. J., & Witkowsky, P. (2021). Deductive and inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. In C. Vancover, P. Mihas, & J. Saldana (Eds.), Analyzing and interpreting qualitative data: After the interview (pp. 133-146). Sage. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/analyzing-and-interpreting-qualitative-research/book270977 ↩

-

Rodriguez, M. Y., & Storer, H. (2020). A computational social science perspective on qualitative data exploration: Using topic models for the descriptive analysis of social media data. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 38(1), 54-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2019.1616350 ↩

Olonilua, O., & Aliu, J. O. (2025). Exploring the Mental Health Impact of Hurricane Beryl on Racial Minorities in Houston, Texas. (Natural Hazards Center Health and Extreme Weather Report Series, Report 6). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/health-and-extreme-weather-research/exploring-the-mental-health-impact-of-hurricane-beryl-on-racial-minorities-in-houston-texas