Place and Process

Earthquake Mitigation in Portland, Oregon

Publication Date: 2024

Abstract

Disaster researchers have found ample evidence that a community’s sense of place is a significant factor in disaster recovery. Few studies have considered the implications that sense of place has on the mitigation phase of disaster management. This research takes a case study approach to a policymaking process in Portland, Oregon that intended to revise statutes governing how to retrofit unreinforced masonry buildings. I sought to answer two questions. First, how do committee members and building owners express their sense of place? Second, to what extent and in what ways did these senses of place influence the mitigation policy process and its outputs? Eighteen semi-structured interviews with building owners and committee members were conducted and over 100 archival documents were reviewed to understand the senses of place that were influential in mitigation processes. Findings from this study offer guidance on how mitigation planning processes can utilize place identities and meanings to address the interests of those most directly impacted by mitigation strategies.

Introduction

The Pacific Northwest is preparing for a high magnitude earthquake unlike any in its recent history. Many cities in this region have made their first order of business to regulate the strengthening of unreinforced masonry buildings, as these buildings have proven to be the least resilient to high levels of ground shaking, consistently resulting in partial or complete collapse. In Portland, Oregon, over 1,600 unreinforced masonry buildings are scattered across the city. This study examines a process to revise building codes to improve the implementation of unreinforced masonry retrofits that took place between 2014 and 2017 in Portland. Unreinforced masonry buildings are older music venues, churches, and schools. Several are on the city’s historic registry, and each offers a sense of charm and history to the built environment. Yet the depth of meaning these sites hold for some Portlanders goes deeper than use or aesthetics: they are symbolic of a place identity and place meaning that are personally and culturally significant. That is, they are integral to individual and community sense of place.

Scholars in urban planning have examined the ways that place influences decision-making, but the unique ways that sense of place shows up in hazard mitigation have yet to be studied. This study aims to fill this gap by seeking evidence as to how much a sense of place influences hazard mitigation for unreinforced masonry buildings. Through document review of archival meeting notes and agendas, and 18 semi-structured interviews with building owners and committee members, this study produces suggestions for a place-informed hazard mitigation process.

Literature Review

Sense of Place

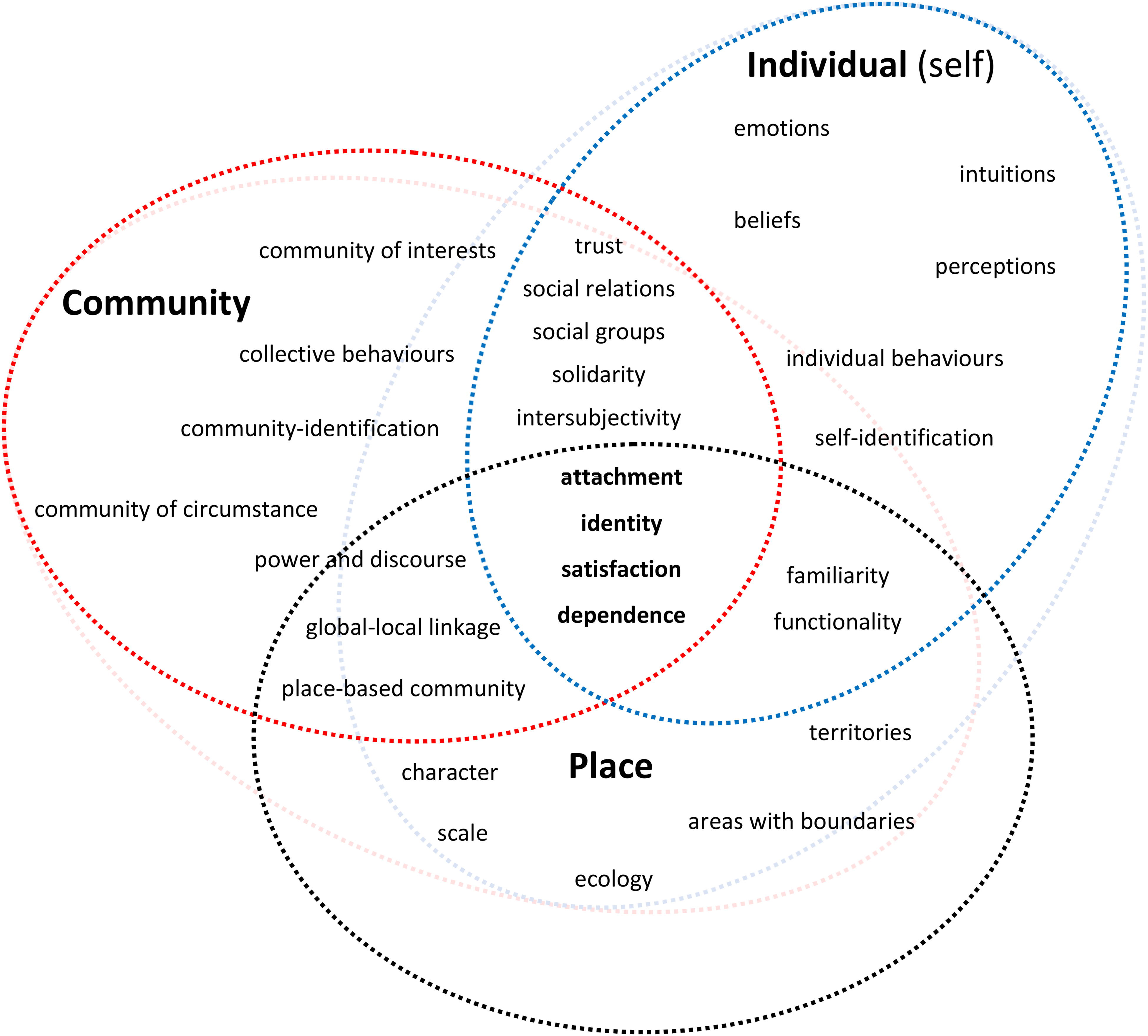

From the humanistic geographic perspective, sense of place is an experience of meaning-making and attachment to a particular setting (Tuan, 19771). When a person feels that they “belong” in a place, and when they are able to perceive the unique character and “spirit of place” there, they have a sense of place (Agnew, 20112; Relph, 2009, p. 273). Beyond the perceptions of human senses (sight, smell, taste, sound, and touch), sense of place is perceived emotionally and psychologically and is often conceptualized as place attachment and place meaning, respectively. Figure 1 displays Erfani’s (2022)4 framework that captures these and the myriad other place-related terms developed and studied to further understand the multi-dimensional phenomenon of sense of place. His work identifies how sense of place emerges from relationships between individuals, communities, and places, and offers a conceptual model useful in analyzing how place interacts in policymaking and planning. In this framework, sense of place is developed through the interrelationship of these three themes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Interrelationships Between Individual, Community, and Place

The relational links between individual and place; community and place; and individual and community offer useful categorizations for interpreting narratives expressed in policymaking and planning (Erfani, 2022). Understanding both individual and community perceptions of place has been proven to minimize or resolve disagreement in planning processes (Erfani, 2022; Manzo & Perkins, 20065).

Sense of Place in Planning

Planning scholars have identified several ways in which the interrelated concepts of sense of place influence planning processes. For instance, place-based memories have been found to shape what beliefs people hold about a place, which impacts how planning strategies are perceived and supported or not (Yeh & Lin, 20196). Place meanings—or the meanings that people have encoded into a landscape or particular location—give planners with different priorities or viewpoints common ground, which is useful in muddling through contentious topics and impasses (Manzo & Perkins, 2006). Still others have found that place-frames, or the discourses developed to describe a shared vision of a place, are used to position groups as they engage in political processes (Martin, 20037).

Place identity also impacts planning processes. Place identity can be interpreted in two ways. First, it can describe the way a person identifies with a place (e.g., “I’m a Portlander”), which is an emotional attachment that can have divisive effects when dismissed or misunderstood (Peng et al.,, 20208). Second, place identity can refer to the way a place is perceived as having particular qualities (e.g., “keep Portland weird”). This “place identity as place” interpretation has long been used to develop visions for planning processes (Stewart et al., 20049; Peng et al., 2020).

Sense of Place in Hazard Mitigation Planning

Hazard mitigation planning consists of risk assessment; long-term strategizing to protect people and property; implementation of devised strategies; and ongoing plan evaluation and updates (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 202310). While the literature suggests that sense of place has many lessons to offer planning, it has yet to be explored holistically for mitigation planning processes. The isolation of mitigation planning from day-to-day planning in cities and towns has proven problematic, as it separates mitigation plans from already existing relationships and power dynamics (Kusumasari et al., 201011). Scholars have called for more collaboration between emergency management and planning processes, especially in the pre-disaster stage (Shmueli et al., 202112).

In disaster studies, place-related phenomena have been found to influence individual choices, behaviors, and well-being. Most research has investigated how sense of place influences individual behaviors as communities recover from the impacts of disaster. Destruction of meaningful places, such as one’s home or historic and cultural sites, has been found to have lasting negative effects on individual mental well-being as well as community identity (Spoon et al., 202013; Sobhaninia et al., 202314). While some people may find that their sense of place is irreparably lost and choose not to return (Chamlee-Wright & Storr, 200915; Spoon, 2020), others feel so rooted to a place that they return to their homes and businesses to restore their sense of place (Chamlee-Wright, 2009; Xiao et al., 201816). Actions to restore sense of place have proven to improve a person’s well-being during disaster recovery (Chamlee-Wright, 2009; Xiao et al., 2018). These findings underscore the significant role that sense of place has on behavior and disaster recovery, but a gap in understanding whether and how sense of place is influential throughout disaster mitigation remains. This study aims to assess a mitigation planning process using Erfani’s (2022) sense of place framework to understand the extent to which sense of place is already operating in those processes.

Research Questions

This study examined a process to revise building codes for the seismic retrofit of unreinforced masonry in Portland, Oregon. The study asked two related questions:

- How do committee members and building owners express their sense of place?

- To what extent and in what ways did these senses of place influence the mitigation policy process and its outputs?

Research Design

As an experiential phenomenon, sense of place is best explored through either firsthand experience or retelling and reflection on an experience. Therefore, these questions were answered through a qualitative approach consisting of document review and semi-structured interviews to capture how sense of place was experienced throughout the policymaking process. The findings presented herein draw on review of over 100 documents related to the four-year policymaking process to revise unreinforced masonry building codes for seismic strengthening in Portland, Oregon. In addition to document review, 18 interviews were conducted with unreinforced masonry building owners (9), Policy Committee members (8), and city staff (1) to fill in the emotional and experiential gaps that documentation left unexplored.

Study Site and Access

This research focuses on a mitigation planning process that occurred between 2014 and 2017 and includes outputs that were produced in 2018. At the time, the Portland Bureau of Emergency Management17 was instructed to coordinate a policymaking process to revise building codes for unreinforced masonry, which are typically, but not always, older buildings of the red-brick variety. As their name references, these buildings lack steel reinforcement in their walls, which makes their composition fragile and vulnerable to ground-shaking. The City of Portland (2017) identified over 1,600 unreinforced masonry buildings within the city limits, including schools (44), places of worship or faith-based activity (38), and multifamily residences (248), the latter of which were largely apartment buildings comprising more than 7,000 residential units. The buildings were mostly used for office space, followed by apartment dwellings. Roughly 35% (or 587) of the buildings identified were on a national or local historic registry.

Unreinforced masonry buildings are common across the United States. This particular process and location were chosen due to unique signals that were emerging from the Policy Committee proceedings in late 2017 and subsequent outcomes of the process as a whole. It was clear then that significant community pushback was a hot topic, as it was prominent in news headlines for several months. The process also raised awareness of the code change impetus: a magnitude 9.0 earthquake is predicted sometime over the next 50 years along the Cascadia Subduction Zone. News articles often highlighted individual stories of property owners’ financial risks and the feeling of not being included in the committee proceedings. Further investigation of these individual stories via public testimony proved that several of them began with speakers’ connection to place, both in terms of unreinforced masonry buildings and the City of Portland.

Document Review

To revise the city code regarding mitigation of unreinforced masonry buildings, the City of Portland developed a three-phase committee-based process, each committee focusing on different aspects of policy design: financial strategies, seismic standards, and policy writing. Documents reviewed included public testimony records and meeting notes from each committee, as well as internal “core” meetings among city staff and sub-group meetings for special topics (i.e., affordable housing and historic preservation). These documents were procured through public request using the City of Portland website or by coordinating with a contact working for the city.

Semi-Structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews focused on the experience of engaging with the Policy Committee or any previous and subsequent unreinforced masonry policy engagement. Interview questions centered on participants’ relationship to unreinforced masonry buildings, experiences in them, and their perception of the building(s). In addition, interviewees were asked to reflect on the racial contexts of unreinforced masonry buildings, with reference to a rally held by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 2018. Finally, interviewees were asked to describe their experiences participating in the policymaking process. These key topic areas were presented as conversation flowed and were not the only topics discussed. However, stylistically, place-related questions were typically presented first because process-oriented questions often returned vivid and painful recollections, which were best explored after a relationship had been built between researcher and participant. See Appendix for the full interview guide. Interviews took about an hour to complete and were conducted either over the phone, through video conference (Zoom), or at a physical site of the interviewee’s choosing.

Sampling Strategy

Interviewee selection was narrowed to four categories: building owners, committee members, staff, and community stakeholders (e.g., residents in multifamily buildings, church members). The only requirement for selection was engagement in the process in some capacity, which included a role as a committee or staff member in the formal (city-sponsored) process; documented oral or written testimony; attendance at a public community engagement session; and any form of self-identified engagement in informal processes such as lawsuits, rallies, or other activities.

Participant Recruitment and Consent

To identify and contact interviewees, I mined internet resources and public documents, including meeting notes and public testimony, for names and contact information. Committee members’ names, representing a total of 18 potential interviewees, were easily identified via public record. Six staff members were identified as engaged in the process. Contact information for staff was located using the City of Portland website.

Potential building owner interviewees were identified through careful review of public testimony records. A total of 80 names were identified in public testimony, of which 25 had no documented contact information. In addition, 17 were omitted due to having a business interest in disaster technology or being a legal representative or lobbyist. This left 38 initial viable building owner interviewees. Each potential interviewee was then emailed or called to be introduced to the research and invited to participate, with no more than two follow-up contacts. Significant barriers were encountered in trying to identify residential tenants, as several years had passed since the process concluded and names of attendees were not on public record. To date, no resident stakeholders have been identified.

Data Analysis Procedures

Documents and interviews were analyzed for indication of sense of place influencing the policymaking process. Interviews were transcribed using Zoom transcription capabilities or, in the case of in-person and phone interviews, a third-party transcription service. Documents and transcripts were then coded in ATLAS.ti (version 8.0.3) using Erfani’s (2022) interrelated themes as primary categories. Each code category was then thematically analyzed to identify the distinct sub-categories or themes used to present findings herein. Using those themes, outputs from the policymaking process—including final policy committee recommendations and a draft ordinance that was never adopted—were examined for indications that these place-related themes were considered in final deliberations.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

Research design was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Portland State University. As per IRB requirements, each person who agreed to be interviewed was provided a verbal consent document for their review upon scheduling an interview. The consent form described the potential risks and benefits of participation and how data collected would be managed and used during and after the research period. Consent was reviewed at the beginning of each interview and participants were then asked to provide consent to participate or not, with the opportunity to ask questions for clarification. Consent to participate was collected verbally.

Findings

Conversations with interviewees indicated that place-related themes were present in the unreinforced masonry buildings case. As Erfani (2022) indicated, these themes arise in the interrelations between individual/self, community, and place.

Individual-Place

Individual-place relationships were evident in both discussions of the unreinforced masonry policy revision process and in written testimony. Place identity is a prominent theme emerging from this interrelationship, with building owners and committee members alike recognizing the significance of unreinforced masonry buildings to both place and sense of self.

Several interviewees talked about how unreinforced masonry buildings are what “make Portland, Portland.” When asked to discuss further what this phrase meant, interviewees mentioned quaintness, unique architecture, and the notion of main streets where commercial and community activities are centralized in many small corridors across the city. As one interviewee described: “Portland is a big city made up of small neighborhoods that are almost like their own little town.” Building owners take pride in being able to maintain older architecture and retain some of the city’s unique aesthetic. As one testimonial stated: “Our family was born in and around Portland and love our city for its historically unique architecture, entrepreneurial attitude, and its willingness to help small and interesting businesses thrive in a culture of acceptance and diversity.” Other public testimony refers to the significance of unreinforced masonry buildings in this vision of Portland: “My buildings are not just brick and mortar. My buildings make a neighborhood.” Another member of the public remarked, "We are the fabric of the community. We are what makes each neighborhood identifiable and Portland the city people love." Unreinforced masonry buildings are integral to the urban landscape, support small businesses, and signify the small-town spirit of the city.

Recommendations made similar reference to this place identity in the opening sentences of the recommendations report: “They include historic churches, schools, and theaters, as well as restaurants, breweries, dance halls, and other landmarks that Portlanders know and love. [Unreinforced masonry] buildings define the character of many Portland neighborhoods and business districts” (Portland Bureau of Emergency Management, 2017, p. 4). The recommendations also discussed the specific contributions of unreinforced masonry buildings that are used for affordable housing, schools, religious organizations, non-profit activities, and historic structures. These considerations suggest that individual-place connections were shared among committee members and building owners, and that place identity was influential in the vision for policy recommendations.

Yet while the recommendations indicate a shared place identity, interviews suggest a personal, or individual, sense of place identity was also influential. Interviewees recognized a particular subset of unreinforced masonry building owners whose tenants were small, local businesses and grouped them with building owners who themselves lived or worked in their unreinforced masonry buildings. Smaller building owners expressed care for the character and history of their buildings and what they meant to the city. These smaller building owners were perceived as quite different than “big developers” who have multiple large buildings in their portfolios. By contrast, interviewees and individuals giving public testimony described big developers as not caring for the city’s people or character. The following quote is an example of this sentiment:

All the new buildings are, so many of them, they don't fit the neighborhood at all. Like there's, you know, very few developers have their buildings designed to fit in with, you know, with the area that's, you know, more historic area.

Another interviewee remarked,

Portland's claim that "Main Streets" are an important part of our city does not jive with the "oh well" attitude toward demolitions in the report. Furthermore, the policies skew toward being forced to sell to "deep pocket" developers at a diminished value. Developers that will demolish buildings.

The “us-versus-them” narrative in these interpretations of mitigation strategies strengthened the place identities of smaller building owners. They perceived their role as safeguarding these historic and small-business assets as a personal responsibility to a city they cherish.

Proposed mitigation strategies were perceived as a threat to these personal place identities. Retrofitting unreinforced masonry buildings was viewed as cost prohibitive for smaller building owners. While many timeline and financing strategies were outlined in committee recommendations, none were viable at the time the recommendations were published. This meant that mandates to retrofit could only mean loss of revenue, displacement of tenants, sales of properties (which were assumed to be acquired by big developers), and/or complete demolition and rebuilding of unreinforced masonry buildings. The future looked bleak. In public testimony, one person stated, “This mandate is the earthquake we all fear…Buildings will be rubble.”

Community-Place

Community-place interrelations reveal a sense of place tethered to place meaning for the larger Portland community. As previously mentioned, historic unreinforced masonry buildings and unreinforced masonry buildings that offered affordable housing were given focus in the decision-making process, as were schools and religious uses. Sub-groups were developed to understand the particular hurdles that religious and other non-profit organizations, as well as historically registered properties, would encounter in implementation. These types of unreinforced masonry buildings offer important services to Portland’s communities, but interviewees and public testimony pointed to further community-place relationships that were omitted from recommendations and the proposed ordinance.

Many of the community-place relationships centered on place meanings for specific racial or ethnic groups. A leader from the local Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association wrote about several unreinforced masonry buildings that were important to the Chinese legacy in Portland, including the building that the association has operated from its inception to this day. In public testimony, one member of The Grieg Lodge spoke to the potential consequences a retrofit mandate would have on the Norse Hall, a site for Norwegian culture, including language and dance lessons, as well as clubs for film, literature, and history. They stated: “We would all be displaced by this mandate and if it passes it [Norse Hall] will be torn down. There is great ethnic and historic value here.” Racial and ethnic relationships to buildings were not discussed in the committee process.

Religious uses, though considered with greater care in the committee process, carried layered meanings that were not broached. Many if not all of Portland’s Black churches were on the City of Porland’s list of identified unreinforced masonry buildings, but the historical and racial context of mandate implications were not considered. Many of the racial implications were only revealed after a proposed ordinance was made public. In written statements and a public rally, a then leader of the Portland Chapter of the NAACP spoke to the impact that proposed policies would have on Black churches specifically, noting that “There are at least 50 African American churches that are on the [unreinforced masonry] list.” The apparent overlook of racial implications for mitigation policy throughout the unreinforced masonry process is made publicly prominent through the NAACP efforts and had significant impacts on the outcomes of the policymaking process, as noted by one interviewee: “A number of these buildings on the list are actually Black churches. And then there was a big uprising. When that happened, the city basically knew they had to change their tune.” In addition, another interviewee added:

Were it not for the minority community in our city stepping up and saying, “Hey, you guys are with our churches ... We can't afford this stuff,” that was the catalyst, because I think it gave a really poor political perspective on this whole process.

Community-place relationships reveal a dismissive attitude toward cultural meaning in mitigation planning, suggesting that place meanings may offer inroads into identifying community-based implications of mitigation strategies.

Individual-Community

Not surprisingly, the unreinforced masonry mitigation planning process was political. Themes of power and the politics of place emerged from the individual-community relationship. Massey and colleagues (2009)18 discuss the politics of place as any sort of contested process about the nature of a place, or one in which the question at hand is, “What does this place stand for?” (p. 411). In this particular place-defining process, very powerful stakeholders were present while often underrepresented stakeholders remained excluded. This exclusion is evident in the omission of racial implications from committee recommendations, as well as the failure to include smaller building owners in the process.

However, building owners and other established community-based groups were able to mobilize into powerful positions during and after the decision-making process. Building owners organized across an otherwise dispersed geography of unreinforced masonry buildings to form Save Portland Buildings, a group whose purpose was to develop and mobilize alternative mitigation strategies that would be feasible for smaller building owners like themselves. Coalitions formed across music venue groups, anti-demolition groups, NAACP, and the newly formed Save Portland Buildings. The coalitions, as well as other groups forming in response to the decision-making processes, came to committee meetings to observe and speak, when allowed. Lobbyists for Masonry Building Owners of Oregon were in the crowd for public meetings and their representatives were on the Policy Committee, along with national Building Owners and Managers Association representatives. Individuals came to public meetings to promote their businesses, offering life-safety systems among the other mitigation solutions being considered. Historic preservationists, geologists, architects, and finance experts each weighed in through public testimony periods or writing letters to the Portland Bureau of Emergency Management, the Mayor, or City Council. These groups were empowered to speak to their diverse interests in unreinforced masonry building policies.

Among those operating businesses from or living in unreinforced masonry buildings on a daily basis, there was but a murmur. Building users, both residents and commercial tenants, wrote a sprinkling of public testimony and a few may have attended the informational session open to residents. Still others were among the building owners living in or operating from the unreinforced masonry building they owned. The omission of diverse and plentiful input from building users is made clear in a letter from City staff to City Council presenting final recommendations:

Considering the limited participation of [unreinforced masonry] building users in the policy process, and given that the proposed [unreinforced masonry] building retrofit standards will not prevent the collapse of many [unreinforced masonry] buildings in an earthquake, staff also recommend two additional steps to protect the interests of the public (Exhibit A, 2018, p. 5).

Those steps added to recommendations a mandate to place a public placard on all unreinforced masonry that informed the public that the building was constructed of unreinforced masonry and posed danger in the event of an earthquake. The steps also recommended a mandate to notify all building tenants of the risks of unreinforced masonry. While these mandates were developed in the spirit of protecting building users, they were not designed in conversation with them. These additional mandates were key factors in the subsequent lawsuit building owners won against the City. A second iteration of unreinforced masonry code revisions started a year later but ended soon after at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, building users continue to live and work in unreinforced masonry buildings.

Interviewees who had lived in unreinforced masonry buildings at the time of this process, or who had close relatives who lived in unreinforced masonry buildings at the time, reported that they had since moved out of those units because they did not feel safe there. Residents became afraid of their apartments and condos after the risk of unreinforced masonry became public knowledge. Public testimony largely shared similar sentiments. One tenant wrote that she supported tenant notification in a mandate, as she was previously unaware that she was living in an unreinforced masonry building. Another tenant stated, "As a tenant, it seems very odd that informing residents of the fact that they live in a [unreinforced masonry building] is such a low priority in the [unreinforced masonry building] report."

Residents did not deny their affection toward these buildings but had to compromise between affection and fear: "I'm a tenant. I want to be safe. I also have a home, that I love and a fair landlord who maintains a building that demonstrates as well as any the culture and aesthetic of Old Town Portland." As designed, the decision-making process did not create spaces for those directly impacted to be involved in the planning process, including residents and building owners. That meant that owners and tenants did not have the opportunity to negotiate through their relationships to the unreinforced masonry buildings.

Discussion

The findings from this study provide evidence to sense of place having influence on mitigation planning. Place identity in particular revealed the importance of stakeholders’ memories in a place, as well as their hopes for the place’s future. A person’s sense of identity as it relates to place proved to be particularly powerful among building owners. Their organizing and mobilization called for the development of a place-frame—the discourses of a shared vision of a place as they engage in political processes (Martin, 2003)—based on their identities. Specifically, they discussed how unreinforced masonry buildings represent “mom and pop shops,” historic buildings, affordability, and main street character—the essence of Portland. These discourses only strengthened the way building owners perceive themselves and their responsibility to the city to uphold and preserve unreinforced masonry buildings for the future. As mitigation plans intervened in the preservation of a place identity, it was viewed as a threat. Mitigation may always be conceived in the spirit of preserving humanity, but the initial changes that it incurs can be detrimental to senses of place and self.

Several of the locations in Portland that are unreinforced masonry buildings are also culturally significant sites that add to senses of place and belonging in the communities they serve. The committee members in the unreinforced masonry case seem to have been negligent in acknowledging or considering the implications mitigation would have on these locations or were unable to identify more specific implementation strategies beyond the broader groups of “historic” or “affordable.” This finding suggests a need for more intricately defined mitigation strategies that take place meanings into consideration. Place meanings have been found useful for finding common ground across diverging perspectives (Manzo & Perkins, 2006), but here they are useful in identifying whose place meanings are included and whose are not.

A question of “who” is prominent across all the themes in this study. Interviewees are each defending their relationships to place, each wanting to preserve “their” Portland. Most of the people expressing this place-protective position are doing so because they were not included in the mitigation process from the beginning. Who is invited to hazard mitigation planning is increasingly significant, as mitigation of hazards edges closer and closer to being a day-to-day planning operation. The politics of place demonstrate the power dynamics of a given political environment, which in this case gave priority to technical expertise, historic significance, and finance over ownership, cultural heritage, and day-to-day use of the buildings. These orientations signify the values upheld by the city.

A place-informed mitigation process would root down in the landscape, asking first “whose place is this?” The answer would require knowing what businesses are run there and by whom. In the case of residential buildings, it would require identifying who is living there. Ownership would then come into play to determine how the parcel is divided and who owns what. Other important information to consider would be who the members of the community are, which people regularly frequent the community businesses, and the ways that the building fits into the spirit of place on a given block or neighborhood. Buildings that are dispersed across a city may require a more localized approach to mitigation. Mitigation planning processes may also be considered spaces for emotional processing, where the people who care for a place are able to grieve loss and work together creatively to preserve what they can. More creative and flexible policies would ease the frustration of sudden change and would convert these “little earthquakes” into community and place-based changes processed as a collective rather than carried by a single individual.

Hazard mitigation planning can be a highly technical space dominated by experts in engineering, finance, and utility infrastructure—to name a few—who often have only one consultation with community members. Community resilience scholarship has paved the way for community-inclusive disaster processes that engage community members as equal partners. Community resilience practices need to translate to hazard mitigation planning and any place-informed mitigation planning process has to be undertaken with the community at the table. The findings in this study point toward some useful considerations for emergency managers and planners as they work with those most directly impacted by mitigation strategies.

Conclusions

Implications for Practice or Policy

Analyzing sense of place in hazard mitigation planning has identified several place-related tools that are useful for decision-making processes. A place-informed mitigation practice requires partnering with the people who actually use a building or site on a regular basis. Hazard mitigation planning has been and continues to be a highly technical space, but it needs to also be a space where community members lead the way. Those who bear the burden of direct impacts from mitigation strategies must be involved in every step. Where residents and businesses cannot engage in lengthy planning processes, they need to be asked who they would like to represent their interests. Identifying who uses a building and what those buildings mean to the communities using them is a pathway for evaluating whether or not the right stakeholders are being recruited.

Identifying various place identities can help stakeholders acknowledge the variation of place-based memories and imagined futures each person holds. Differentiating between a place identity versus a sense of self that identifies with a place will help differentiate between the vision of place that frames the process and the many different emotional relationships people have with a place. Once those individual-place relationships are identified, it is important to continue to acknowledge them, connect them to strategies, and show that those people-place relationships influence mitigation choices. These direct throughlines will signal care for preserving sense of place throughout mitigation and may minimize the feeling that a person’s place identity is being threatened.

Limitations

This study was limited by the availability of residential tenant records, which has made identifying residents who engaged in the processes quite challenging. The findings heavily relate to building owner experience while acknowledging the need for more insights from building users. Another limitation has been time, in the sense that a lot of time has passed since the mitigation process began and concluded. Interviews are often introduced in terms of “memory work,” and a few interviews were declined because the heightened emotions had passed or people felt they would not remember enough. Finally, this is one mitigation planning process in a mid-sized urban environment and will not necessarily reflect other processes to revise unreinforced masonry building codes.

Future Research Directions

Future research would further develop discrete guidance on place-informed mitigation processes. The breadth of place-related ideas presents an overwhelming number of entry points into understanding how sense of place influences process. In addition, studying sense of place in an ongoing process could further test the ideas presented here. Lastly, comparing mitigation processes for unreinforced masonry in similar circumstances could help clarify the transferability of these findings.

Acknowledgments. I am deeply grateful for the Mitigation Matters Award Program and the interviewees who were willing to share their stories with me. Without them this study would not be possible.

References

-

Tuan, Y. (1977). Space and place: The perspective of experience. University of Minnesota Press. ↩

-

Agnew, J. (2011). Space and place. In J. Agnew & D. Livingstone (Eds.), Handbook of geographical knowledge (pp. 316-330). Sage. ↩

-

Relph, E. (2009). A pragmatic sense of place. Environmental and Architectural Phenomenology, 20(3), 24-31. ↩

-

Erfani, G. (2022). Reconceptualising sense of place: Towards a conceptual framework for investigating individual-community-place interrelationships. Journal of Planning Literature, 37(3), 452-466. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122221081109 ↩

-

Manzo, L. C., & Perkins, D. D. (2006). Finding common ground: The importance of place attachment to community participation and planning. Journal of Planning Literature, 20(4), 335–350. ↩

-

Yeh, H., & Lin, K. (2019). Distributing money to commemoration: Collective memories, sense of place, and participatory budgeting. Journal of Public Deliberation, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.322 ↩

-

Martin, D. G. (2003). “Place-framing" as place-making: Constituting a neighborhood for organizing and activism. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(3), 730– 750. http://www.jstor.com/stable/1515505 ↩

-

Peng, J., Strijker, D. & Wu, Q. (2020). Place identity: How far have we come in exploring its meanings? Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00294 ↩

-

Stewart, W. P., Liebert, D., and Larkin, K. W. (2004). Community identities as visions for landscape change. Landscape and Urban Planning, 69, 315–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.07.005 ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2023, November 8). Hazard mitigation planning. United States Department of Homeland Security. https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/hazard-mitigation-planning ↩

-

Kusumasari, B., Alam, Q., & Siddiqui, K. (2010). Resource capacity for local government in managing disaster. Disaster Prevention and Management, 19(4), 438–451. ↩

-

Shmueli, D., Ozawa, C., & Kaufman, S. (2021). Collaborative planning principles for disaster preparedness. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 52, 101981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101981 ↩

-

Spoon, J., Hunter, C., Gerkey, D., Chhetri, R., Rai, A., Basnet, U., & Dewan, A. (2020). Anatomy of disaster recoveries: Tangible and intangible short-term recovery dynamics following the 2015 Nepal earthquakes. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101879 ↩

-

Sobhaninia, S., Amirzadeh, M., Lauria, M., & Sharifi, A. (2023). The relationship between place identity and community resilience: Evidence from local communities in Isfahan, Iran. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 90, 103675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103675 ↩

-

Chamlee-Wright, E., & Storr, V. H. (2009). “There’s no place like New Orleans”: Sense of place and community recovery in the Ninth Ward after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Urban Affairs, 31(5), 615–634. ↩

-

Xiao, Y., Wu, K., Finn, D., & Chandrasekhar, D. (2018). Community businesses as social units in post-disaster recovery. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 42(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18804328 ↩

-

Portland Bureau of Emergency Management (2017). Unreinforced masonry (URM) building policy committee report, December 2017. City of Portland. https://www.portland.gov/pbem/documents/urm-policy-report-dec-2017/download ↩

-

Massey, D., Research Group, H. G., Bond, S., & Featherstone, D. (2009). The Possibilities of a Politics of Place Beyond Place? A Conversation with Doreen Massey. Scottish Geographical Journal, 125(3–4), 401–420. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.pdx.edu/10.1080/14702540903364443 ↩

Mercurio, S. (2024). Place and Process: Earthquake Mitigation in Portland, Oregon. (Natural Hazards Center Mitigation Matters Research Report Series, Report 21). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/mitigation-matters-report/place-and-process