Assessing Impacts of Hurricane Maria for Promoting Healthcare Resilience in Puerto Rico

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

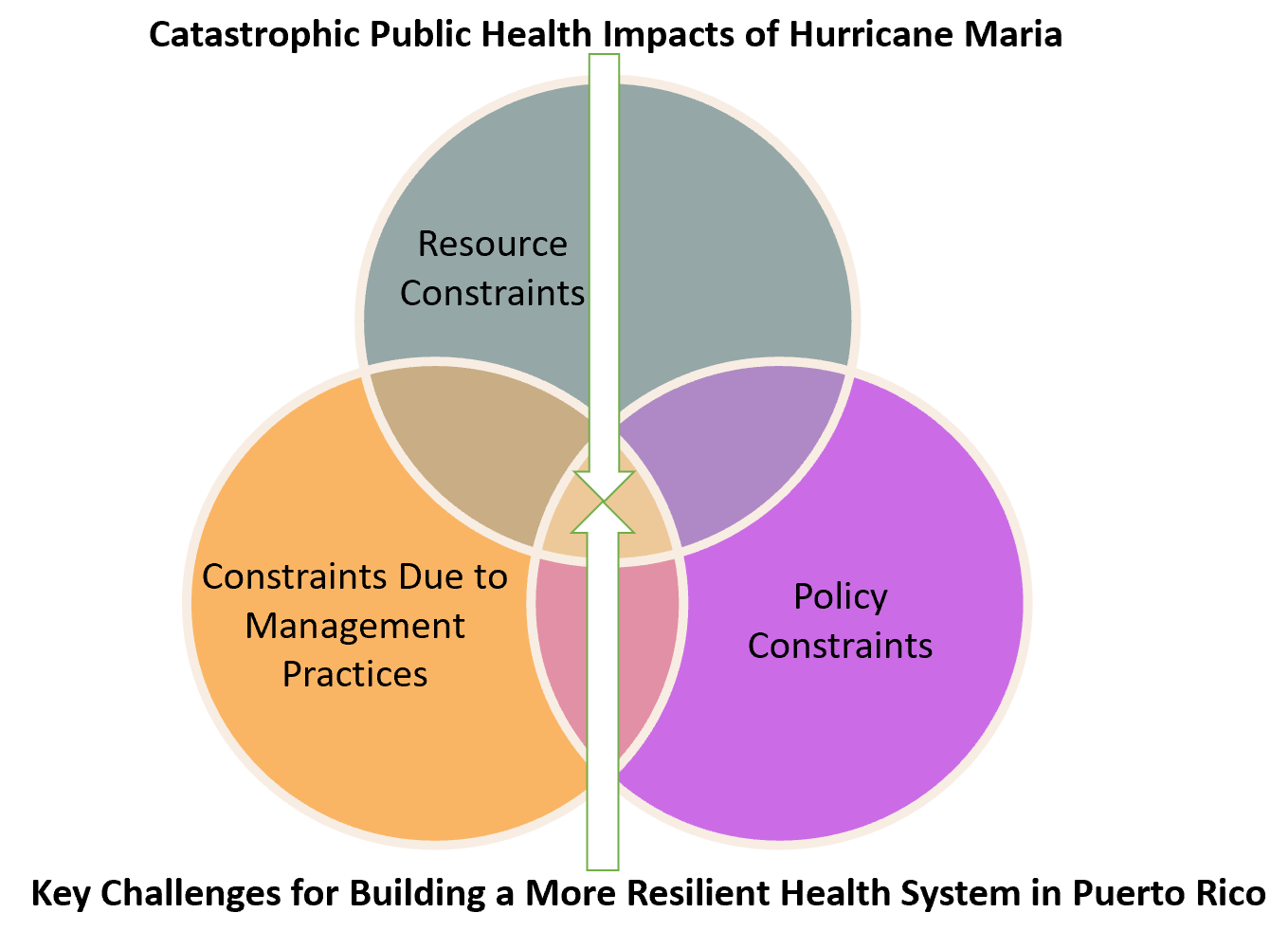

Given the rising exposure to coastal hazards in highly vulnerable areas like Puerto Rico, there is a growing urge to integrate natural hazards risk into public health preparedness for enhancing community resilience. How healthcare providers, hospital management staff, nonprofit and community organizations, public health practitioners, emergency management personnel, and the public interact in responding to natural hazards is critical for building a resilient healthcare system in affected communities. Against this backdrop, we conducted interviews to gauge the perspectives of patients, public health professionals, and emergency management personnel to gain deeper insights into the nature and extent of key public health management challenges following recent disaster events in Puerto Rico. The main research questions are: (a) to what extent are these key challenges due to resource constraints, (b) to what extent are they due to management practices and policy constraints, and (c) what are the actionable steps that can be specified to overcome these constraints for reducing mortality and morbidity risks during future disasters? The preliminary findings indicate that high mortality and morbidity risks in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico were primarily driven by resource constraints, which were further aggravated by management practices and policy constraints. Our findings have significant implications, as it can potentially help build a conduit between the community, public health stakeholders, and emergency management agencies for laying the foundation of a resilient health system in Puerto Rico.

Introduction

The health system in Puerto Rico faces unique challenges in maintaining resilience and continuity during natural hazards or disaster events. Previous studies have shed light on specific aspects of health system resilience, such as the role of healthcare workers (Niles & Contreras, 20191), the capacity of healthcare facilities (Rios et al., 20212), and the need for improved emergency preparedness plans (Noboa-Ramos et al., 20233). While these investigations have provided valuable insights, they have primarily focused on individual components or isolated healthcare facilities. In contrast, our research takes a comprehensive approach by examining the broader aspects of health system resilience in Puerto Rico and exploring strategies to ensure the system's functionality during crisis events (Kruk et al., 20174).

The main objective of our study is two-fold. Firstly, we aim to determine the extent to which key post-hurricane challenges are due to resource constraints, management practices, and policy constraints, thereby gaining a comprehensive understanding of the underlying causes faced by the public health management system. Secondly, we seek to identify specific mechanisms and actionable steps to enhance disaster preparedness and reduce the risks of disaster-related mortality and morbidity. Through the identification of effective strategies and fostering dialogue and cooperation among these key stakeholders, we aim to lay the foundation for a resilient health system not only in Puerto Rico but also in other vulnerable coastal regions facing similar challenges. The significance of this topic extends beyond Puerto Rico, as it encompasses the broader context of the increasing threats posed by extreme weather events and their impacts on public health systems.

We used a mixed-methods approach. We conducted interviews with 62 participants who represented various groups, including patients, public health professionals, utility service operators, emergency management personnel, and other key stakeholders. Our analysis included both descriptive quantitative analysis and thematic qualitative analysis. Our analysis of interviews with diverse stakeholders highlighted important areas for improvement, including the need to reform the electricity supply infrastructure, enhance human resource management, decentralize healthcare delivery, strengthen emergency planning and preparedness, and promote good governance to prevent deaths and mitigate adverse health outcomes. Based on the findings, we suggest that adequate investment in healthcare facilities, infrastructure, and governance is crucial to improving disaster preparedness and increasing the resilience of the healthcare system. The remainder of this report is structured as follows: first we provide a literature review of existing research on public health system resilience. Then, we present our research methodology, including the details of our interviews with key stakeholders in Puerto Rico. Finally, we present our research findings and recommendations, followed by a conclusion.

Literature Review

Since Puerto Rico became a territory of the United States in 1898, its healthcare system has undergone significant changes. Historically, the healthcare system in Puerto Rico was largely dominated by a fee-for-service model, with little emphasis on preventative care or population health management until the 1980s. Since then, preventative care and managed care programs have become more prevalent in the healthcare system, especially after the 1990s (Benach et al., 20195). At present, there are two major types of healthcare systems in Puerto Rico. The public system is managed by the government's Health Insurance Administration and serves the majority of the island’s population. Meanwhile, the private system is managed by private entities and serves a smaller population that can afford to pay through private health insurance (Mulligan, 20146).

Puerto Rico's healthcare system involves various entities that play a crucial role in providing healthcare services. These entities include healthcare providers such as doctors, nurses, hospitals, clinics, and other healthcare facilities, as well as the financing and insurance mechanisms that enable individuals and organizations to pay for healthcare services (Noboa-Ramos, 2023; Perreira et al., 20177; Rios et al., 2021). In 2010, the Puerto Rico government launched a new public health insurance program called Mi Salud to expand access to healthcare services for low-income individuals and families. Regulations also played a significant role in governing the healthcare industry, including the licensing and accreditation of healthcare providers, quality standards, and patient safety measures (Benach et al., 2019). Additionally, the healthcare infrastructure, which comprises tools, equipment, and facilities used to deliver healthcare services, is an essential component of the healthcare system in Puerto Rico. Despite efforts to strengthen the healthcare system, challenges have been reported, including a shortage of healthcare providers, inadequate infrastructure, and difficulties in enacting local legislation and policies. Moreover, the devastating impact of Hurricane Maria in 2017 further exacerbated the strain on the healthcare system (Benach et al., 2019; Noboa-Ramos, 2023; Rodríguez- Díaz, 20188).

In general, resource constraints refer to limitations arising from a lack of resources such as financial, human, and technical resources. Management constraints, on the other hand, refer to limitations or barriers created by management factors such as understaffing, inadequate coordination, and poor communication among stakeholders. Policy constraints refer to limitations or barriers imposed by regulations or laws governing the delivery of health services, including a lack of planning and regulations.

Many studies have highlighted the deficiencies exposed by Hurricane Maria concerning these constraints within Puerto Rico’s healthcare system. For instance, the study by the Urban Institute showed that low capitation rates for Medicare and Medicaid programs and a lack of investment in health care contributed to the challenges faced by the system (Perreira et al., 2017). Similarly, another study by Rodríguez-Madera et al. (2021) found that the absence of a disaster management plan, inadequate funding, understaffing, and a lack of resources and infrastructure contributed to the collapse of the health system during Hurricane Maria. The study also suggested that prolonged power outages and the absence of a disaster management plan were partly responsible for the deaths of 3,052 individuals who experienced an extended interruption in access to medical care. The record loss of lives and extensive disruptions in basic healthcare services following these events point to under-preparedness and a lack of resilience within the system to respond to future crises (Chandra et al., 20189; Meng et al., 202210).

Prior research on this topic has either focused on a limited aspect of the overall health system resilience against natural hazards and disasters or investigated a single healthcare facility. For instance, Niles and Contreras (2019) analyzed the role of healthcare workers in Puerto Rico when healthcare facilities did not function at full capacity and services were disrupted in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. They found that flexible roles in providing services and local knowledge about the service needs were key for continuing medical outreach activities. Rios and collaborators (2021) conducted a case study to assess the capacity of the Community Hospital at the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) in providing healthcare services after Hurricane Maria. They interviewed 13 medical professionals (emergency and family medicine physicians, hospital administrators, and others) from the UPR Community Hospital and found that the staff were unaware of the limited capacity of backup generators at hospitals and lacked a well-coordinated system for transferring ICU patients to other hospitals for needed services. Noboa-Ramos and collaborators (2023) conducted interviews with 52 key informants from healthcare and social organizations in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, highlighting the need for improvement in emergency preparedness plans.

In contrast, our research focuses on the broader aspects of health system resilience in Puerto Rico and explores how the system can be adapted to maintain the core functionalities during crises (Kieny et al., 201411; Kruk et al., 201512; Kruk et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 201313). Specifically, we examine the availability of resources and information to understand the capacity to act and anticipate healthcare emergencies associated with the system and population. We also investigate the integration and coordination mechanisms among diverse stakeholders at different levels, the flexibility and adaptability of the system in distributing and allocating resources and authority, and the availability of diverse healthcare services to address the needs of the population (Kruk et al., 2017). Our mixed-methods analysis combines patients, public health professionals, emergency management agencies, organizations, and institutional leaders to obtain comprehensive insights into this extremely challenging issue.

Research Questions

Motivated by the health system resilience literature (Kruk et al., 2015; Kruk et al., 2017), we asked three overarching research questions:

- To what extent are the key challenges in building a more resilient health system in Puerto Rico due to resource constraints?

- To what extent are the key challenges in building a more resilient health system in Puerto Rico due to management practices and policy constraints?

- What are the actionable steps that can be specified to overcome these constraints for reducing mortality and morbidity risks during future disasters? More broadly, how can we build a conduit between the community, public health stakeholders, and emergency management agencies to lay the foundation for a resilient health system for Puerto Rico?

Figure 1 provides the conceptual diagram of assessing impacts of Hurricane Maria for promoting healthcare resilience in Puerto Rico.

Figure 1. Conceptual Diagram of Assessing Impacts of Hurricane Maria for Promoting Healthcare Resilience in Puerto Rico

Research Design

Study Site Description

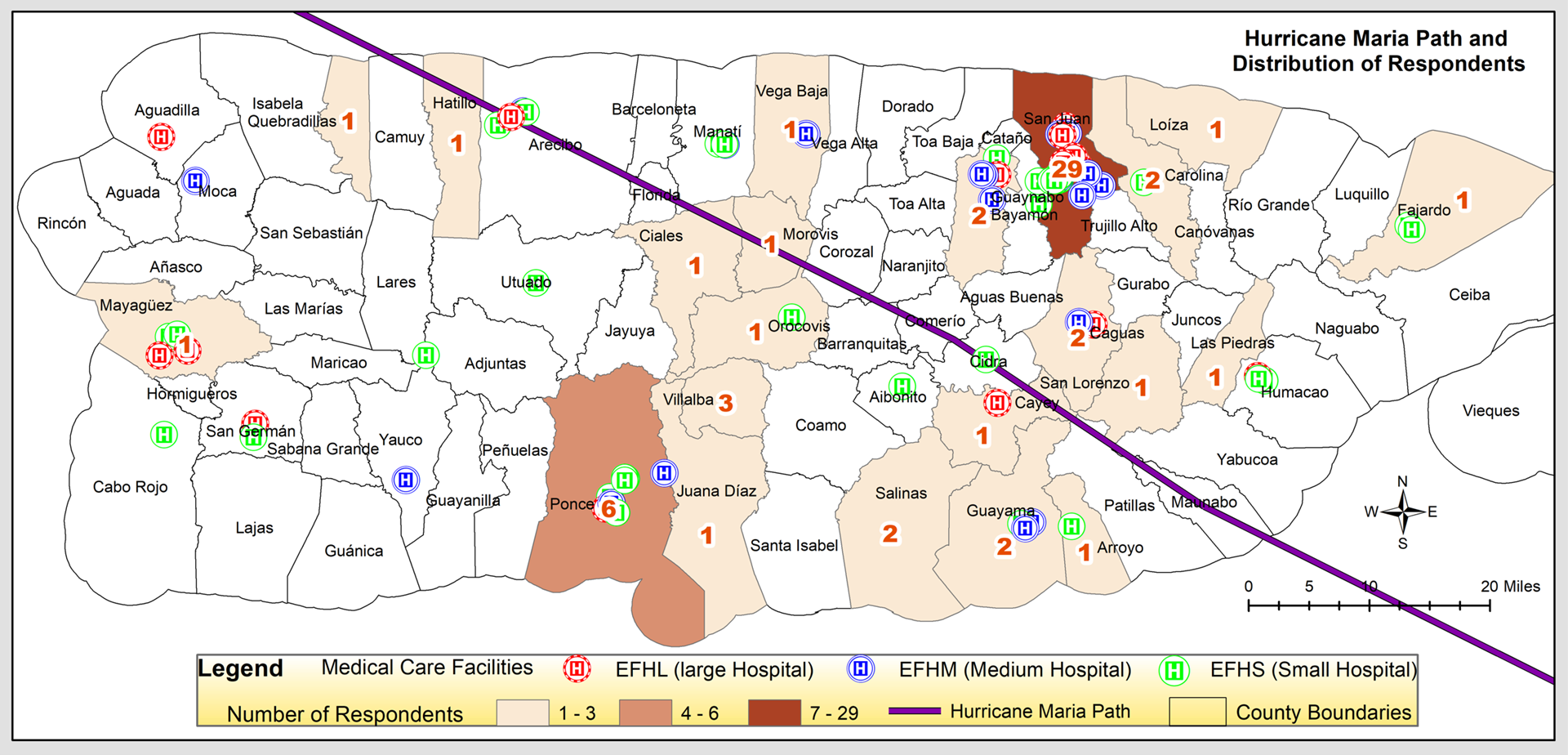

Figure 2 depicts the geographic distribution of hospitals and healthcare facilities in Puerto Rico with their respective capacities categorized as large (>150 beds), medium (50-150 beds), and small (<50 beds). The data was gathered from the HAZUS Essential Facilities Data updated from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Homeland Infrastructure Foundations - Level Data, which provides GIS shapefiles for hospitals on the U.S. mainland and in its territories (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 202114). The healthcare facilities are seen to be clustered around three major cities in Puerto Rico (San Juan, Mayaguez, and Ponce).

Figure 2. Location of Stakeholder Interviews and Capacities of Healthcare Facilities in Major Cities in Puerto Rico

Sampling Strategy

Our sample selection approach was purposive, aiming to capture a diverse range of perspectives. We interviewed 62 participants representing patients, public health professionals (doctors, pharmacists, nurses, hospital administrative staff, caregivers, etc.), utility service operators, emergency management personnel, and other relevant key informants. By incorporating expert and stakeholder interviews with public health and related professionals working in Puerto Rico, we examined the healthcare service disruptions from the supply (provider) side to assess the key factors leading the demand-supply gaps and to identify the major barriers to a resilient healthcare system following a disaster event.

As shown in Figure 1, our sample selection process took into account the diverse sizes and capacities of healthcare facilities in the major urban centers of Puerto Rico. We also interviewed experts and stakeholders that are indirectly related to healthcare provision (e.g., utility and support service providers, emergency management personnel, community organizers, etc.). While we recognize the challenge of reaching out to these diverse groups of stakeholders, locational heterogeneity (socioeconomic characteristics, neighborhood amenities, extent of hurricane exposures, etc.) was considered in the sample selection.

Data Collection

The interviews were conducted either in Spanish or English, depending on the preference of the participant. A team member who is a nurse by profession, has expertise in qualitative methods, and is bilingual conducted the interviews. The U.S. and Puerto Rico-based research team developed the data collection tool collaboratively during the initial project meeting held in Puerto Rico in January 2023. Data collection started in late January 2023 and concluded in April 2023. Each interview took an average of 45 minutes. The interviews were transcribed and translated into English by the same team member who conducted the interviews.

Our tool involved a combination of structured, semi-structured, and open-ended questions. We asked a series of questions about the major challenges faced in managing public health after the hurricane, the type of collaboration sought and with whom, the challenges faced by healthcare professionals and local people when seeking healthcare from insurance providers after the disaster, and the specific challenges related to healthcare provision faced by healthcare professionals such as nurses, doctors, and administrators.

Furthermore, our tools were designed to gather expert and stakeholder perspectives on how to strengthen the structure of the healthcare system to make Puerto Rico more resilient to future disasters. For instance, how new technologies (e.g., solar-powered generators and telehealth systems) could provide more flexible and functional infrastructure for diagnosis and treatment, how community health centers could be integrated with mental health services with better financing mechanisms (e.g., Medicaid/ Medicare payments for covering expenses), and how a digital health information and resource sharing network could improve the standard of care in post-disaster periods. We also sought opinions on how supportive services for the most vulnerable (children, expecting mothers, older adults, people with disabilities, and those with chronic health conditions) could be prioritized, how regulations for emergency health and social service needs could be adjusted, and how improved systems for emergency medical stockpiles and public information campaigns to engage communities in the recovery process could be effectively organized. The expert and stakeholder data analysis aim to facilitate participatory, cross-disciplinary, and cross-organizational dialogues that are instrumental for advancing convergence-oriented research in disaster risk management (Peek et al., 202015; Peek & Guikema, 202116) and enhancing health system resilience on the island.

Data Analysis

We conducted both quantitative and qualitative analyses, which complemented each other to address the key research questions. For the quantitative analysis, descriptive statistical techniques were employed to summarize the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, their experiences during a hurricane, and their opinions on a Likert scale about a range of topics related to building a resilient health system in Puerto Rico. The data analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics (version 29). Frequency distributions and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, while the mean and standard deviation were calculated for quantitative variables. In terms of the qualitative analysis, two members of our study team participated in the process, using a thematic analysis approach. Initially, each member independently analyzed the data using NVivo software for coding. They developed an initial coding scheme based on the interview guide, which was later refined based on the initial review of the transcripts. Next, the members re-reviewed transcripts for more advanced-level coding, and then met to discuss their respective coding and collaboratively develop a unified coding scheme. This iterative process continued until both members agreed that the results were reflective of the data.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

The research activities were conducted after receiving Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval by Florida International University. Any identifiable personal and sensitive health information in stakeholder interviews was protected as guided by the IRB protocol. In the data collection phase, we made all possible efforts to comply with recommended public health measures to protect the research team, local collaborators, and research participants. The research directly involved local collaborators and stakeholders from the beneficiary communities. We have closely worked with our UPR partner and recruited a UPR public health alumni, who is now a nurse by profession, to conduct interviews. We made sure that the interviews were conducted with compassion and in culturally competent ways. For example, when any respondent mentioned that they were feeling stressed to dig out the memory to provide further details on a specific issue, we moved to the next topic.

Findings

Quantitative Findings

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Appendix A summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. A total of 62 people were interviewed, most of whom were nurses (25.8%), patients (12.9%), or doctors (11.3%). Participants also included hospital utility service operators (9.7%), hospital management personnel (8.1%), people from nonprofits, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), or community organizations (6.5%), pharmacists (4.8%), and other relevant key informants (21.0%). This last category included two nutritionists, a rehabilitation counselor, an occupational therapist, a medical social worker, a respiratory therapist, a surgical technician, a ward clerk, a home health aide, a case manager, a clinical informatics officer, and a person from a medical supply company.

Most of the participants were 60 years or older (37.1%) or between 50 and 59 years old (32.3%); the mean age was 54.6 years old. Most of the participants within each of the professional categories evaluated were in these two age groups, except for the hospital utility services operators, where half (50.0%) of the participants were aged 40–49. Participants mostly had a Bachelor’s (32.3%) or a Master’s (29.0%) degree; however, this varied between professionals. Almost all doctors and pharmacists had a doctoral degree, whereas most patients and hospital utility service operators had an associate or technical degree. Almost half of the participants (46.8%) worked in San Juan, the capital of Puerto Rico. The study participants had worked an average of 24.6 years; however, most of the nurses, hospital utility service operators, and other relevant key informants had 20 years or less of professional experience.

Disruption of Services at Workplace

Appendix B summarizes the mean number of days the participants experienced an interruption of services at their workplace due to Hurricane Maria. The services for which participants reported interruptions for longer than a month, on average, were electricity (power) and internet/cyber systems. Participants reported between 0 and 300 days without electricity at their workplace, with an average of about 2 months. Participants reported a disruption of the internet and cyber systems that ranged between 0 and 240 days. The longest average disruptions of these services were reported by patients and people from nonprofits, NGOs, or community organizations, whereas the shortest interruptions were reported by doctors and nurses.

Phone or cell phone services were interrupted for an average of three weeks; the longest average disruption was reported by patients and the shortest by doctors. Services disrupted for about two weeks included water and waste management. Patients reported the longest average disruption of water services, and doctors reported the shortest, whereas hospital management personnel reported the longest disruption of waste management services and nurses the shortest. Participants also reported an unavailability of equipment for providing services, decisions made by upper administration to keep the facility closed, a lack of doctors/nurses in the office, and a lack of other support staff that lasted between one and one and a half weeks. Disruptions in the following services lasted, on average, less than a week: closure of pharmacy/medical supply stores, road and public transportation to get to work, closure of medical test centers, unsafe work environments, closure of ambulance services, and closure of emergency care.

Adverse Events in Workplace/Hospital

Over half of the participants (57.6%) were aware of patient deaths in their workplace/hospital during the period of time that can be attributed to disruptions in providing healthcare services due to Hurricane Maria (see Appendix C). However, this awareness varied by profession: most doctors, nurses, and hospital management personnel indicated not being aware of deaths. In addition, almost all participants (90.2%) from all professional groups were aware of severe health outcomes for patients receiving routine care that could be attributed to hurricane-related disruptions in providing healthcare services.

Current Capacity and Mechanisms of Healthcare Services

A little over half of the participants (56.5%) were very aware of the current capacity and availability of beds, equipment, and facilities in their community, 59.7% were very aware of the capacity and availability of medicines and medical supplies, and 48.4% were very aware of Telemedicine, electronic health record, and communication systems (see Appendix D). Most of the doctors, nurses, hospital management personnel, and other relevant key informants were very aware of all these healthcare resources. Other professionals reported less awareness, particularly people from nonprofits, NGOs, or community organizations and patients.

Only 37.1% of the participants were aware of existing mechanisms between the public and private healthcare providers in their community to maintain core healthcare functioning during and after an emergency. This awareness was reported by most doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and hospital management personnel. Also, most of the participants (59.7%) were aware of mechanisms for tracking progress and evaluating the health system’s performance during and after an emergency. Most of the participants from all the professional groups reported this awareness, except for the patients. Most of the participants (72.6%) from all professional groups indicated that they were aware of specific challenges or issues that the municipality or local healthcare teams encountered in managing healthcare services during and after the hurricane. This was expressed by most of the participants within each of the professional categories (Appendix D).

Healthcare Service and Preparedness

Almost eight out of every ten participants (79.0%) think new technologies (e.g., solar-powered generators and telehealth systems) can provide more flexible and functional infrastructure for responding to a major emergency event like Hurricane Maria. Most of the professionals from each category are of this opinion, except for people from nonprofits, NGOs, or community organizations (see Appendix E). Also, most of the participants (77.4%) think that supportive services for the most vulnerable (children, expecting mothers, older adults, people with disabilities, and those with chronic health conditions) could be prioritized in responding to a major emergency event. Only 21.0% of the participants believed that the government was responsive to the healthcare service needs of the community following Hurricane Maria; most disagreed with this premise (38.7%) or were neutral (33.9%). Only the hospital utility service operators and the people from nonprofits, NGOs, or community organizations thought the government was responsive.

Less than half of the participants (45.2%) reported that they only somewhat trusted the healthcare system to provide necessary and appropriate care when they or their family members needed it, and 38.7% indicated that they mostly trusted the system. Most doctors, pharmacists, and hospital utility service operators mostly trusted the system. Almost all the participants (96.7%) think there is a highly urgent need to integrate natural hazard risks into public health preparedness for enhancing community resilience given the rising exposures to natural hazards in highly vulnerable areas like Puerto Rico. Also, almost all (95.2%) think a dialogue between affected communities, key public health organizations, and emergency management agencies for laying down an actionable foundation of a resilient health system in Puerto Rico will be very useful. Only 11.3% of the participants indicated that they felt that the level of government health expenditure or investment in their community to support functioning healthcare services during and after an emergency was adequate, and over half (54.8%) considered it inadequate. Except for patients and hospital utility service operators, most of the participants from each professional group qualified the level of government expenditure as inadequate.

Healthcare Digital Information and Coordination Systems

About three out of every five participants (59.7%) think that a digital information and coordination system within healthcare facilities across Puerto Rico could ensure interoperability to reduce disaster-related deaths and adverse health outcomes in the future (see Appendix F). This was reported by most of the professionals within each group. Also, 41.9% think this system will be useful when responding to natural hazards after the event; most patients, hospital management personnel, and people from nonprofits, NGOs, or community organizations think it will be very useful. Most of the participants also think that a digital information and coordination system to facilitate communication between healthcare providers, emergency management personnel, and the public/community is very useful in preparing for (69.4%) and responding (56.5%) to natural hazards like Hurricane Maria.

Management Challenges

Almost all the participants considered that all or most of the disaster-related public health management challenges in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria were due to a lack of resources (93.5%), such as a lack of available and functional equipment, a lack of basic utility services, a lack of healthcare professionals, and other human resources and skills, or due to existing practices of the healthcare system (93.4%) at hospitals, clinics, emergency, and urgent care facilities (see Appendix G). These results were similar within all professional groups. About three out of every five professionals considered that all or most of the management challenges were due to the existing health insurance system in Puerto Rico (64.5%) or due to policy constraints at the local level (66.1%). A large proportion of hospital utility service operators, hospital management personnel, and people from nonprofits, NGOs, or community organizations considered that some of the challenges were due to these reasons. Only 37.1% of the professionals considered that all or most of the challenges were due to policy constraints at the federal level. Most of the participants from all the professional groups considered that most or some of the management challenges were due to this type of constraint.

Qualitative Analysis

Impact of Critical Interdependent Infrastructures

Power Infrastructure. The damage to the infrastructure led to an intermittent electrical supply, causing widespread disruption across hospitals and clinics. Healthcare professionals were forced to face numerous challenges, including blackouts during critical medical procedures, which put patients' lives at risk. One nurse poignantly described the situation:

The intermittency in electrical power was … worrisome. Even if it was for seconds, a blackout in the middle of a surgery is desperate. Imagine a neurosurgeon stapling an aneurysm and at that moment there is a power outage; one wrong move and the aneurysm bursts.

The power outages and fluctuations affected the operation of medical equipment, as generators had limited capacity and were unreliable. The power fluctuations led to the damage and loss of valuable medical equipment, including MRI machines, X-ray machines, ventilators, and patient monitors. For instance, a 38-year-old doctor from San Juan recalled a tragic story:

I remember a patient who was discharged during Maria and was taking a medication that thinned the blood... When he returned to the hospital the CT machine was not working due to low voltage. He ended up dying because they couldn't operate on him.

In many cases, people with pre-existing health conditions experienced complications and even fatalities due to the inability to use critical medical equipment at home or in care facilities. In addition, the lack of electricity had far-reaching consequences, as one hospital management personnel in San Juan noted that people in some areas went without power for months, leading to several problems such as the inability to refrigerate medication and the lack of power to run medical equipment.

Back-up Generator. The damage to the power infrastructure forced many healthcare providers to rely on back-up power, such as generators, which often provided limited power and could not fully support the needs of medical facilities. As a nurse with 33 years of experience recounted, “Although there was a generator, many times it did not come on in time. If the operating room was more than 30 minutes without power, it was an emergency for any surgery.” At medical centers across the island, healthcare providers were already accustomed to working with limited supplies and resources. However, the devastation brought on by Hurricane Maria amplified this issue, with one medical service administrator from San Juan lamenting:

Here at the Medical Center, there is always a lack of supplies, and no one can hide that... But in María, we had a lot of needs, equipment, replacement of parts. Well, the most painful thing was not having battery backup for equipment that can cost the life of a patient.

The power crisis extended beyond hospitals and into the homes of bedridden patients who relied on biomedical equipment. Another medical administrator shared:

I heard from more than ten people, all bedridden people who needed some biomedical equipment in their homes and had problems with the generators. Some did not have generators and other cases were that their relatives could not get gasoline for their generators.

Transportation Infrastructure. The damage to the power system also affected transportation infrastructure, making it difficult for healthcare professionals to travel to work and for patients to access healthcare services. For some patients, the damage to roads and bridges proved to be a significant barrier to accessing healthcare services. For instance, a wheelchair-bound patient from Orocovis (a municipality in the mountainous center of the island) found himself trapped in their home due to fallen trees and impassable roads. Similarly, a patient from Salinas (a municipality in the south) reported hearing about an acquaintance who passed away in their home in the Damián neighborhood of Orocovis, as there was no way to transport them to the emergency room. The destruction of infrastructure also led to a disparity in the distribution of aid, as remote communities struggled to receive the help they needed. Healthcare providers were frustrated with the concentration of aid in the capital, San Juan, which left rural areas to manage with limited resources.

Similarly, one of the challenges reported was the absence of traffic lights on the roads. “There were no traffic lights on the roads; trying to drive in the metropolitan area was life-threatening at all times,” reported a doctor from San Juan. The absence of traffic lights caused long delays and even accidents, which made transportation a significant challenge in the aftermath of the hurricane.

Communication Infrastructure. The impact of Hurricane Maria on the communication infrastructure was significant, leaving many without any means of communication. People had no access to phones, internet, or other modes of communication. Few cell phone towers were working. Some people were without communication for up to three weeks, causing distress and uncertainty. One patient from Ciales (just north of Orocovis) shared, “We were incommunicado; there was no passage for more than two weeks.”

The lack of communication had far-reaching consequences. A doctor from Juana Diaz (east of Ponce on the south of the island) noted, “The communication problem was the accelerator for so many misfortunes. [...] The problem was that we couldn't reach the people who really needed us. Many people were too long incommunicado.” This lack of communication made it difficult for medical professionals to coordinate care and provide help to those in need. The breakdown of communication infrastructure also made it difficult for people to access basic services and resources. Many mentioned that the lack of power and the limited availability of cell service made it difficult to stay in touch with loved ones. The lack of communication infrastructure also made it difficult for medical professionals to provide care, particularly to patients who needed urgent medical attention. In summary, Hurricane Maria caused a breakdown of the communication infrastructure and system, leaving many without access to basic services and medical care. The lack of communication made it difficult for people to coordinate care and access resources, resulting in significant distress and uncertainty.

Basic Resources and Supplies

The lack of electricity affected the availability of gas for transportation and generators in medical facilities, further complicating the ability of healthcare professionals to provide care and reach their workplaces and patients. A nurse from San Juan recounted their difficulties, saying:

I didn't have gas to get to work; a colleague and I had to ask for the same shifts to be able to share the gas. One day I arrived, and I had no gasoline to return home. I stayed in the hospital for two days waiting for gasoline.

These experiences highlight the numerous obstacles faced by healthcare professionals in the wake of the hurricane as they struggled to maintain essential services and provide care to those in need. Similarly, the hurricane caused a scarcity of food and essentials in many areas, leading to difficult conditions for the people affected. The destruction of the transportation and communication infrastructure also made it difficult to distribute and supply food and other essential items to the affected areas. Healthcare providers also reported difficulty in providing basic needs such as food, water, and medications due to the lack of power and transportation.

Furthermore, the impact of Hurricane Maria on the water supply in Puerto Rico was devastating. With the power system damaged, essential services such as water supply and sanitation were affected, leading to difficulties in maintaining hygiene and cleanliness in healthcare facilities, as well as providing basic needs such as food, water, and medications. As one nurse from San Juan noted:

There was instability in the electrical system and in the water system. This insecurity kept us waiting for the medical equipment to be turned off or that we would not even have water to wash our hands.

The impact of water shortage extended beyond basic needs and cleanliness. “The lack of drinking water. There are always cases of leptospirosis in Puerto Rico. But, definitely, after Maria there was an epidemic,” a doctor from San Juan Medical Center noted. The most vulnerable populations, such as those living in nursing homes, suffered the most from the lack of water and basic needs. Overall, Hurricane Maria's impact on the water supply in Puerto Rico had severe consequences on the health and well-being of the population, highlighting the need for better disaster preparedness and response.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, healthcare providers and residents of Puerto Rico faced a severe shortage of medical supplies. Hospitals were initially equipped with enough supplies to last only a few days, but the weeks-long interruption of essential services quickly depleted their resources. This shortage extended beyond hospitals and directly affected the people of Puerto Rico. For instance, one individual who relied on an oxygen tank was unable to receive a supply for almost two weeks, eventually succumbing to the damage caused by the lack of oxygen. Patients with chronic conditions, such as those dependent on oxygen tanks, were severely affected by the lack of access to medical assistance. For instance, a hospital service operator from San Juan mentioned:

An acquaintance used an oxygen tank and was unable to get a supply for him. When they managed to contact me (because they know that I work at the Medical Center) he had been without his oxygen supply for almost two weeks. I looked for a way to bring him a tank full of oxygen. But those two weeks without his oxygen did him a lot of damage. When I went to bring him the tank, he was no longer the same, he was fading and two days later he died.

The lack of access to medical assistance also led to patients rationing their medication or sharing with their neighbors, as one nurse from Ponce observed: “Getting the medicines was difficult; I know of people who divided their pills and took half the dose they needed. Others shared medicines between neighbors, even if it was not the same medicine, they said: ‘we are both diabetics and worse is nothing.’”

Capacity and Commitments of Human Resources

Shortage of Human Resources and Work Overload. In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, the healthcare system in Puerto Rico faced unprecedented challenges. One of the most significant issues was the acute shortage of healthcare professionals. Healthcare providers, such as doctors and nurses, were stretched to their limits as they grappled with the immense workload caused by the disaster. As one doctor from San Juan recounted, “the Trauma Center had to close for several days due to being completely overloaded, with patients being referred to the federal government's Comfort ship for treatment.” Patients, too, noticed the significant impact of the worker shortage. One patient from Arroyo (municipality on the southeast) expressed that there is a “difficulty in finding paramedics, ambulances, nurses, and other support staff, with no clear channels for expressing concerns or complaints.”

The situation was exacerbated by healthcare workers having to work long hours without breaks and, in some cases, even sleeping in the hospitals due to transportation challenges and the need to continually provide care. This dire situation was further intensified by the pre-existing shortage of specialists in Puerto Rico, which only worsened following the hurricane. As noted by one of the respondents:

Many health service providers left the island and never returned, leaving the few remaining clinics struggling to cope with the demand. Patients who would normally see primary care providers were arriving at specialist clinics in record numbers, resulting in wait times of six to eight months for appointments.

The collective experiences of both healthcare providers and patients underscore the immense pressure the Puerto Rican healthcare system faced in the wake of Hurricane Maria. The limited resources, coupled with a significant loss of human resources, left many providers working non-stop and experiencing work overload, further highlighting the urgent need for support and recovery in the region's healthcare infrastructure.

Mental Health Challenges. The aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico had a devastating impact on the mental health of healthcare workers, patients, and the elderly population. According to a nurse from the University Medical Hospital in San Juan, “The biggest challenge was maintaining my mental health, everyone's mental health was affected.” She also described the difficulties of commuting to work, saying “I travel from Caguas to San Juan and that is a challenge, getting up in the morning because one wants to provide the service as a nurse.” Meanwhile, a doctor from a Medical Center in San Juan reported a rise in suicides and psychosomatic symptoms among the older adult population. “After the scourge of Hurricane Maria, an alarming increase in suicides and suicide attempts was noted. The elderly population is the one that is suffering the most,” he said. A nurse from an elderly home in Hatillo (municipality on the northwest) also highlighted the impact on mental health, stating “You cannot cover the sun with one hand; the mental health of my clients and employees was tremendously affected.”

Plans and Policies

Hurricane Maria exposed numerous challenges stemming from a lack of government action, preparation, and communication. Communication from officials was virtually nonexistent, leaving residents feeling abandoned. Some mentioned that there was no communication from the government. Furthermore, the absence of emergency plans exacerbated the situation, as a home health aide from Ponce (big city on the south) stated, “public health here in Puerto Rico are useless; they have no plan for anything.”

Healthcare professionals faced multiple challenges, including a lack of guidelines, resources, and support from insurers. Strict policies from insurers, unclear patient coverages, and pre-authorization challenges only added to the difficulties faced by the healthcare sector. One hospital service operator from San Juan explained, “The offices of the medical plans closed; they have pre-authorization policies and in those circumstances, with their offices closed, there were no pre-authorizations.” Referrals presented another challenge, as a patient from Ciales (located north of Orocovis) said, “The biggest challenges faced by insurers is having to request referrals in order to receive medical services and specialized studies.”

Inadequate disaster preparedness and response plans, limited access to medical equipment and supplies, and the breakdown of communication systems further exacerbated the crisis. These highlight the need for comprehensive plans, policies, and resources to address such disasters.

Collaboration, Communication, Coordination

In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, one of the most significant challenges faced by the people of Puerto Rico was the lack of communication between stakeholders. The devastation caused by the storm disrupted essential services like electricity, water supply, transportation, and telecommunications, making it incredibly difficult for individuals, health workers, and emergency responders to coordinate and provide services and resources. As one respondent mentioned, “The biggest challenge was the distance between people’s homes and the mountainous terrain that made it difficult for aid to reach people” (Patient, Ciales). Medical professionals struggled to reach patients in remote areas, while administrators and staff in health centers faced an uphill battle to secure resources and support. The disconnection between various stakeholders further exacerbated the existing crisis, as people were left to navigate the chaos on their own, with limited information and guidance.

The lack of collaboration and coordination between stakeholders also led to duplication of interventions and an inefficient distribution of resources. A representative from a nonprofit organization in Quebradillas (northwest municipality) shared their perspective on the issue stating, “There was a lot of duplication of interventions. Many times, a sector was impacted by many suppliers at the same time, duplicating efforts and leaving other areas without services, supplies, and equipment.”

Furthermore, it is evident that top-down or unilateral decision-making has contributed to dissatisfaction and frustration among medical professionals. The medical planners, driven by financial interests, dictate which patients require services and which do not, leading to an ongoing conflict with doctors and patients. The funds that could be utilized to improve patient care are instead being siphoned off as administrative expenses, further highlighting the negative impact of unilateral decision-making in this context. This top-down approach has obstructed collaboration between diverse stakeholders.

Conclusions

Public Health Implications and Policy Recommendations

Below, we report respondents’ five major recommendations, with three including both short-term and long-term components. Appendices H and I summarize the findings and recommendations by themes and sub-themes from the qualitative analysis.

Reforming Electricity Infrastructure

Respondents recommended restoring power in hospitals following a power outage during a hurricane.

Short-Term Recommendations. Respondents recommended the government to prioritize restoring power after a hurricane. Further they recommended the hospitals to diversify their electricity sources, by installing solar panels to charge generators and batteries used for service delivery on hospital premises.

Long-Term Recommendations. The respondents recommended that the government establish robust electricity infrastructure in Puerto Rico so that electricity interruption is never an issue during a hurricane. Many called upon the government to enact policies now to avoid any power outages in a future hurricane. One of our interviewees, a hospital manager in San Juan, illustrated this point: “Of course, the most logical recommendation is to improve the electrical distribution system in Puerto Rico.”

Authors’ Recommendations. Hospitals may explore partnerships with a solar company in order to install solar panels at a discounted price. The government can extend tax incentives by way of encouraging the installation of solar panels in hospitals, or through cross-sectional collaboration between hospitals and solar companies.

Improving Human Resource Management

Respondents recommended better human resource management for the healthcare industry in Puerto Rico.

Short-Term Recommendations. The respondents recommended remunerating healthcare providers (e.g., doctors) competitively, so that they are motivated to work in Puerto Rico and not to emigrate to the United States.

Long-Term Recommendations. Respondents recommended better utilization of the cadre of nurses in Puerto Rico, many of whom are highly skilled. Respondents recommended engaging nurses in a more advanced level of healthcare provision in the aftermath of a hurricane, when there are more patients seeking care than typical.

Authors’ Recommendations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has online training for public health supervisors and managers that may help the hospital management personnel assess staff satisfaction, burnout, stress, and mental health during or after a hurricane. The hospitals may convene a daylong meeting with nurses and state officials to determine the feasibility of engaging nurses in more advanced healthcare provision. Meanwhile, the hospitals may engage nurses in providing healthcare and counseling via telehealth, as part of emergency planning and preparedness, to at-risk populations (e.g., older adults) and communities (e.g., mountainous communities).

Emergency Planning and Preparedness

The respondents recommended the government and hospital administration to undertake a more targeted approach in their emergency planning and preparedness programs and policies.

Short-Term Recommendations. The respondents recommended the government to prioritize the older adult population in state-led evacuation and emergency preparedness activities. They recommended the government to educate older adults on how to prepare for sheltering at home by (a) stocking up on food, water, medicine and special equipment when applicable, (b) planning for power outages, and (c) identifying a support system to reach out to for emotional support (Halim et al., 202117). The respondents opined similarly regarding how to best help the population needing special care (e.g., sleep aid kit) during evacuation. Respondents recommended the government to use social media for the dissemination of public messages. Further, respondents recommended the government to require all organizations, including hospitals, to have an emergency plan. As for hospitals, respondents recommended triaging patients presenting at the emergency department in a hospital, based on needs.

Long-Term Recommendations. Several respondents recommended the government to develop a census of at-risk people in disaster-prone communities (i.e., those prone to experiencing more severe health outcomes including older adults, patients requiring medical equipment, or those living in mountainous areas). A patient in Salinas illustrated this point:

I believe that health services should be better prepared, especially in mountainous areas…at the level of the neighborhoods, in the municipalities of the center of the Island, clinics are needed, that way when the roads are obstructed it would not be such a big problem. Situations like Hurricane Maria or worse may recur in the future if mountain neighborhoods do not have quality medical services. The citizen who cannot leave those places because the passage has been obstructed by landslides or because bridges and highways have disappeared, well, he dies in his house. Medical services are needed in all these places because it is the only way to prevent so many deaths.

Several respondents recommended upending the current city planning to make cities more resilient to hurricanes. A patient in Arroyo provided a quote illustrating this point:

I believe one cannot wait for the hurricane to be announced to begin cleaning and maintaining bodies of water, sewers, and roads, knowing that this is a country with severe flaws in construction planning... Well, prevention in flood-prone areas and constant pruning of trees to facilitate the reconstruction of the flow of electricity would have prevented many calamities.

Finally, several respondents recommended universal healthcare by way of bypassing insurance companies. As a representative from the nongovernmental sector in Loiza said:

If the public health system were universal, where everyone was treated with the same urgency, it would prevent some health insurance from becoming rich and others impoverished. The above expressed leading to a debacle in the health system, where some have everything, and others lack an adequate and vital health system for survival.

Authors’ Recommendations. The government of Puerto Rico can use the CDC’s social vulnerability index to guide its efforts to identify at-risk communities. Further, the government can consult with such resources as CDC’s Incident Management System or the National Hazards Center’s Risk Communication and Social Vulnerability: Guidance for Practitioners document to guide its efforts to communicate about preparedness and safety messages with at-risk populations.

Decentralizing Healthcare

Long-Term Recommendations. Several respondents recommended to decentralize healthcare delivery (a) from San Juan to all other areas including mountainous communities and regions, and (b) from hospitals to community clinics. Several respondents mentioned that community clinics would improve access to health care among those unable to access hospital-based care easily (e.g., older adult population), enabling care for a vast number of patients in their own communities, and only referring to hospitals to those needing tertiary level care. They recommended staffing community clinics with nurses. As a nurse in San Juan said:

Many people come to the Medical Center, but do not need super tertiary care. I can give that primary care in the community and possibly if I have a doctor, four nurses, a psychologist and a social worker in a school that is empty example: ‘Fulana de Tal [similar to Jane Doe but in Spanish], come this way, look, your blood pressure is high. You should go to your cardiologist. Fulana, you have diabetes, your sugar levels are a little high, let's do a glycoside test.’ I don't have to wait for that patient to become chronic before they arrive at the supra tertiary hospital. These are things that I can do in my community, with little money and few resources.

Good Governance

Long-Term Recommendations. Numerous respondents discussed the need for good governance as key to reducing casualties and adverse health outcomes, especially after a hurricane. They cited the need for better management of emergency funds so that the funds go to eligible recipients. The respondents also discussed the need for autonomous disaster management agencies so that they are free of any political pressure. As a patient in Vega Baha said: “Let the funds reach the people. The government keeps the money and disappears without the work being seen. If funds are spent where they should be used, services can be improved before disaster strikes.”

Figure 3 presents the recommendation for multilevel interventions to reduce casualties and adverse health outcomes in the aftermath of a hurricane event in Puerto Rico.

Figure 3. Recommendations for Multilevel Interventions to Reduce Casualties and Adverse Health Outcomes in the Aftermath of a Hurricane in Puerto Rico

Limitations

There are some limitations of this study that should be acknowledged. We were unable to recruit an equal number of stakeholders (i.e., providers, patients, community representatives, NGOs, etc.) as intended. Rather, our sample includes more nurses than any other provider type. As a result, the findings may be skewed to represent the opinions of nurses. Second, our analyses are based on the opinions of those agreeing to participate in the study. We don’t have a systematic estimate of all who were approached and of those who were ultimately interviewed. Future researchers may consider conducting a stakeholder analysis using the implementation science framework and the Delphi method to assess the feasibility of implementing these recommendations.

Strengths

In this study, we investigated the health impacts of disasters in Puerto Rico and the pressing need for promoting resilience. Our main objective was two-fold: first, to determine the extent that key challenges that arise after a hurricane are due to resource constraints or management and policy constraints; and second, to identify specific mechanisms and actionable steps to enhance disaster preparedness and mitigate the risks of disaster-related mortality and morbidity. Based on the quantitative and qualitative analyses of on-site interviews, we obtained valuable insights from public health experts, emergency management agencies, communities, organizations, and institutional leaders on how to build a more resilient healthcare system in Puerto Rico.

The findings indicate that high mortality and morbidity risks in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico were primarily driven by resource constraints which were further aggravated by existing management practices and policy constraints. The quantitative analyses reveal that disruptions in workplace services caused significant difficulties in providing effective health care, and the lack of resources, such as limited personnel, and existing policy and management practices, such as unclear patient coverages and pre-authorization issues, exacerbated these challenges. Participants believe that new technologies and a digital information system will facilitate better coordination and improve the healthcare infrastructure. They also feel the urgency of integrating natural hazard risks into public health preparedness.

The qualitative findings confirm the challenges of providing effective health care amidst service disruptions, a shortage of human resources, and access issues for patients needing medical assistance. Recommendations from the participants include reforming the electricity supply infrastructure, improving human resource management, decentralizing healthcare delivery, enhancing emergency planning and preparedness, and introducing good governance to prevent deaths and reduce adverse health outcomes. Our findings have significant implications, as it can potentially help to build a conduit between the community, public health stakeholders, and emergency management agencies for laying down a foundation of a resilient health system in Puerto Rico.

Acknowledgments. We extend our deepest gratitude to all respondents who took time from their busy schedules to sit for interviews for this project.

References

-

Niles, S. & S. Contreras. 2019. Social Vulnerability and the Role of Puerto Rico’s Healthcare Workers after Hurricane Maria. Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Grant Report Series, 288. University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/social-vulnerability-and-the-role-of-puerto-ricos-healthcare-workers-after-hurricane-maria ↩

-

Rios, C. E., Ling, R. R., Gutierrez, J., Gonzalez, J., Bruce, M., Barry, & Perez, V. J. (2021). Puerto Rico health system resilience after Hurricane Maria: Implications for disaster preparedness in the COVID-19 era. Frontiers in Communication, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.593939 ↩

-

Noboa-Ramos, C., Almodóvar-Díaz, Y., Fernández, E., & Joshipura, K. (2023). Organizations’ disaster preparedness, response and recovery experience: Lessons learned from Hurricane Maria, Journal of Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 17, E306. https://doi:10.1017/dmp.2022.272 ↩

-

Kruk M. E., Ling, E. J., Bitton, A.,. Cammett, M., Cavanaugh, K., Chopra, M. et al. (2017). Building resilient health systems: A proposal for a resilience index, British Medical Journal, 357, j2323 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2323 ↩

-

Benach, J., Díaz, M. R., Muñoz, N. J., Martínez-Herrera, E., & Pericàs, J. M. (2019). What the Puerto Rican hurricanes make visible: Chronicle of a public health disaster foretold. Social Science & Medicine, 238, 112367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112367 ↩

-

Mulligan, J. M. (2014). Unmanageable care: An ethnography of health care privatization in Puerto Rico. NYU Press. ↩

-

Perreira, K., Peters, R., Lallemand, N., & Zuckerman, S. (2017). Puerto Rico health care infrastructure assessment. Health Policy Center. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/puerto-rico-health-care-infrastructure-assessment-site-visit-report ↩

-

Rodríguez-Díaz, C. E. (2018). Maria in Puerto Rico: Natural disaster in a colonial archipelago. American Journal of Public Health, 108(1), 30-32. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304198 ↩

-

Chandra, A., Marsh, T., Madrigano, J., Simmons, M. M., Abir, M., Chan, E. W., Ryan, J., Nanda, N., Ziegler, M. D., & Nelson, C. (2017). Health and social services in Puerto Rico before and after Hurricane Maria: Pre-disaster conditions, hurricane damage, and themes for recovery. Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center, Rand Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2603.html ↩

-

Meng, S., Halim, N., Karra, M., & Mozumder, P. (2022). Understanding household evacuation preferences during the COVID-19 pandemic in Puerto Rico. SSRN. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4011468 ↩

-

Kieny, M. P., Evans, D. B, Schmets, G., & Kadandale, S. (2014). Health-system resilience: Reflections on the Ebola crisis in Western Africa. Bulletin of World Health Organization; 92, 850. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.14.149278 ↩

-

Kruk, M. E., Myers, M., Varpilah, S. T., & Dahn, B. T. (2015). What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet, 385(9980), 1910-1912. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60755-3 ↩

-

Thomas, S., Keegan, C., Barry, S., Layte, R., Jowett, M., & Normand, C. (2013). A framework for assessing health system resilience in an economic crisis: Ireland as a test case. BMC Health Service Research, 13, 450. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-450 ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2021). HAZUS Inventory Technical Manual. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_hazus-inventory-technical-manual-4.2.3.pdf ↩

-

Peek, L., Tobin, J., Adams, R.M., Wu, H., & Mathews, M. C. (2020). A framework for convergence research in the hazards and disaster field: The Natural Hazards Engineering Research Infrastructure CONVERGE Facility. Frontiers in Built Environment, 6, 110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2020.00110 ↩

-

Peek, L. & Guikema, S. (2021). Interdisciplinary theory, methods, and approaches for hazards and disaster research: An introduction to the special Issue. Risk Analysis, 41(7), 1047-1058. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13777 ↩

-

Halim, N., Jiang, F.. Khan, M., Meng, S., Mozumder, P. (2021). Household evacuation planning and preparation for future hurricanes: Role of utility service disruptions, Transportation Research Record, 2675(10). https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981211014529 ↩

Mozumder, P., Rodriguez-Figueroa, L., Quiles-Miranda, M., Manandhar, B., Meng, S., & Halim N. (2023). Assessing Impacts of Hurricane Maria for Promoting Healthcare Resilience in Puerto Rico (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 32). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/assessing-impacts-of-hurricane-maria-for-promoting-healthcare-resilience-in-puerto-rico