Exploring the Long-Term Impact of Cascading Disasters in the U.S. Virgin Islands on High School Student and Teacher Mental Health and Resilience

Publication Date: 2021

Executive Summary

Overview

This study was designed to investigate the impact of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in September, 2017, on the mental health, resilience, and outlook of high school students and teachers in St. Thomas and St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands. These two Category 5 hurricanes caused extensive damage to housing and infrastructure and disruptions to transportation, the electrical grid, and education.

Research Questions and Design

While studies have looked at disaster impacts on the well-being of elementary and middle school students, fewer have researched high school students. In addition, previous studies have focused on the impacts of single events over short time spans. Our study addresses longer-term impacts. The study was guided by four questions: What were the most important stressors for high-school students recovering from disasters? To what extent does the long-term stress of disasters impact student well-being and graduation outlook in high schoolers? How do students and teachers cope with the longer-term effects of Hurricanes Irma and Maria? How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted teacher and studen thoughts, feelings, and outcomes compared with the impact from the hurricanes?

A sample of 38 teachers and 66 students completed the study. Our mixed-method design used an online survey and semi-structured interviews for data collection. We used correlations, cross tabulations, and key themes to communicate the findings. Our results show that more female (30%) than male students (5.3%), and 30% of teachers suffered from lingering post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) three years after the disasters. The symptoms they experienced included avoidance behavior, re-experiencing trauma, and hyperarousal. We also found the highest significant correlation between students who had to relocate on-island and overall PTSD scores (rs(59) = 0.325**). Students who experienced damages from both hurricanes had higher rates of PTSD characteristics than those who were dealing with damage from only one hurricane or no damage at all. More than 51% of teachers were still bothered by the effects of the hurricane despite only 33.3% suffering damages to their homes.

Preliminary Results

Interviews revealed coping strategies that were grounded in the Caribbean mindset as hardy people. Respondents believed that others fared worse and that both teachers and students had similar experiences. While both students and teachers had high emotional resilience scores that helped to offset the negative bias score associated with hypersensitivity to stress and negative outcomes, teachers had higher social skill scores and showed greater capacity to seek support and engage socially.

Conclusions

Students were also given opportunities to talk and write about their experiences as coping strategies. The fact that they were suffering from PTSD three years later indicated the inadequacy of these strategies. Students revealed that COVID-19 had a far worse impact on their educational performance than the hurricanes. Interventions and strategies that helped students, especially females, cope with disasters must be offered long term. This may include providing teachers with the training and skills they need to provide longer-term support for students. Periodic assessments of the implementation and effect of these strategies should also be conducted. More studies need to be done and volunteers need to be encouraged to participate in similar studies to continue to measure the effects of the disasters and find the best strategies to address PTSD in the long term.

Introduction

Disasters that occur in quick succession, often referred to as cascading disasters, have raveged lives and property throughout the world. A September 23, 2020 report from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Center stated that more than 51 million people experienced disasters during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 (Walter & van Aalst, 2020). While overlapping extreme weather events coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered research at such intersections, this experience seems typical for St. Thomas and St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI1). On September 20, 2017, the USVI was devastated by Category 5 Hurricane Maria, while still reeling from the destruction of Hurricane Irma, another Category 5 hurricane that had struck on September 6. More than 90% of the utility infrastructure was destroyed and 70% of the housing stock was damaged or impacted by the hurricanes. More than three years later, students and teachers continue to deal with various recovery challenges. Some schools were still operating in temporary modular buildings and some families were still living in homes that were not yet repaired. In the USVI, the uncertainty, risk and drastic changes to the normal educational and work environments with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 further complicated the recovery from the cascading hurricanes of 2017.

Three years after Hurricanes Maria and Irma, schools in the USVI were still in recovery mode and stress remains a challenge. The Caribbean Exploratory Research Center in collaboration with the University of the Virgin Islands conducted a community needs assessment of children and families in the USVI in early 2019 and found that all modular schools were erected as of December 2018, modified school days and instruction were still ongoing, and more than 23,000 primary residences were damaged by one or both hurricanes (Michael et al, 20192). Stress was identified as a major challenge for students, families, and education administrators. Some families were still displaced and school staffing had not returned to normal (Michael et al, 2019). Wasonga, Christman, & Kilmer (20033) also suggested that school students may become more stressed when attention is not paid to the non-instructional aspects of schooling. Michael et al., (2019) confirmed that many afterschool programs were either suspended or significantly reduced even 15 months after Hurricanes Irma and Maria. This study used online surveys and Zoom interviews to examine student and teacher emotional well-being, and to learn how they have coped three years after the devastation caused by Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Since schools were operating virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person recruitment of high school juniors and seniors and teachers was impossible.

Literature Review

Children’s vulnerability to disaster impacts and the psychological effect of disasters on them and their families has been well documented (Fothergill, 20174; Peek, 20085; Silverman & La Greca, 20026; Norris et al., 20027). These vulnerabilities have been classified as psychological, physical, and emotional (Peek, 2008). Psychological vulnerabilities include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, emotional distress, among others (Peek, 2008). The psychological, physical, and educational vulnerabilities of children and adolescents after disasters are influenced by factors such as delayed enrollment in school, unsupportive school personnel, a lack of social support, physical loss or vulnerabilities, family separation, child demographics, negative coping skills, and parental distress (Peek, 2008). While several studies have identified the vulnerabilities that children face, plans for disaster mitigation and recovery have often overlooked the mental health needs of children and adolescents (Anderson, 20058). Assessing their perspectives may lead to more inclusion in recovery planning. High school students may be among the most vulnerable children. They are at greater risk than element and middle school students because they have less time to complete their pre-college education and are likely to face greater challenges from disasters that set back or shorten the length of their high school education.

The degree of a child’s exposure to disasters often determines their ability to cope. These exposures have been used as the basis for mental health service interventions that were often based on their disaster exposure. Schools have been identified as ideal spaces for administering these interventions (Lai, et al, 20169; Peek & Richardson, 201010). Coping has been defined as a persistently changing cognitive and behavioral process by which individuals combat or prevent stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 198411). Feinauer, Middleton & Hilton (200312) found that children who developed higher levels of existential well-being cope with challenges better. However, the needs of children were often overlooked by adults including parents and teachers who assumed that children were resilient and unaffected by changes associated with disasters (Silverman & La Greca, 2002). Factors such as reductions in the school lunch program, delayed school reopenings, and family stressors such as unrepaired homes can affect student mental health, reduce enrollment, and increase the drop-out rate (Michael et al., 2019; Aja et al., 201813). Therefore, understanding children’s perspectives of what stresses they face and how they cope was essential (Peek & Richardson, 2010).

Teachers, students, and schools in general, struggle with disaster response and recovery. In the USVI, for example, two of three permanent buildings that make up the Charlotte Amalie High School that were damaged by the 2017 hurricanes were condemned by FEMA in 2019 after finding structural deficiencies that had at first been missed (Gilbert, 201914). Now, the school will be conducting in modular units indefinitely, which adds to the struggles that teachers and students already face. Also, previous work conducted in Dominica in the Caribbean region showed that transitioning school buildings from serving as temporary shelters back to serving as schools was not a major priority leaving students displaced from their classrooms for extended periods (Serrant, 201315). Similarly, Aja et al., (2018) indicated that students from the University of Puerto Rico attended classes under tarps and that this contributed to the detrimental effects of the hurricanes on the psychology and emotional well-being of students there. Other studies suggest that unmet behavioral health needs of students can undermine their ability to cope and successfully graduate from their school (Michael et al., 2019; Wasonga et al., 2003). Therefore, it was important to assess what stresses student and teachers face during the long-term recovery from multiple disasters.

Students from families who experience post-traumatic stress and depression after disasters can have difficulty bouncing back. Kousky (2016) identified several ways that children were affected by disasters: direct impact and loss, indirectly through parent and household impacts and loss, and associated parental stress. Michael et al., (2019) suggested that there was a strong correlation between hurricane impacts and negative mental outcomes in middle schoolers. However, they did not identify what gaps in services exist for high schoolers in the USVI who were recovering from cascading disasters in the long term. They recommended interventions to address various forms of PTSD and depression that students may exhibit including a call for policymakers to address social determinants of health (Michael et al, 2019; USDHHS, 202016). Wasonga et al., (2003) further contended that ethnicity, gender, and age were moderating factors that affected how students bounced back. Other studies showed that geographic factors (urban versus rural settings) and economic factors (such as level of poverty) were also moderating factors (Hallegate et al., 2020). It was important to determine how high school students dealt with post-traumatic stress, whether male and female students perspectives differ, and how to tailor interventions to address their needs.

Quickly offering social support can buffer the impact of disaster related and lead to better mental health outcomes for adolescents and contribute to greater post-traumatic growth and positive outcomes (Mooney et al., 202017; Hobfoll, 200218; Norris et al., 2002). In this light, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO19) signed an agreement with the Caribbean Development Bank in June, 2018 to conduct an 18-month project that will “enhance capacity for mental health and psychosocial support in disaster management” in the Caribbean. However, this project failed to adequately substantiate data on the long-term effects of disasters on the mental health of children and adolescents in the region. Intervention needs to be systematic and tailored (Silverman and La Greca, 2002). Very few studies, however, have demonstrated what interventions work best to address children’s mental recovery from disasters in the long term.

In summary, much of the research on child vulnerabilities and experiences during cascading disasters come from parent and teacher perceptions rather than from the children themselves (Eder & Fingerson, 200220). Since high schoolers are not passive victims and can communicate their own risks, vulnerabilities, and outcomes, this research aims to capture their voices and fill the gap in literature. We directly questioned high school students using an initial close-ended survey questionnaire followed by an in-depth interview with students who were amenable to explaining their answers. Our findings will provide student and teacher perspectives on the role schools played in helping them cope with the long-term effects of disasters.

Research Design

Research Questions

The research questions for this study included:

- What were the key stresses faced by high-school students recovering from cascading disasters?

- To what extent did the long-term stresses of cascading disasters impact student well-being and graduation outlook in high schoolers?

- How have students and teachers cope with the longer-term effects of Hurricanes Irma and Maria?

- How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted teacher and student thoughts, feelings and outcomes compared with the impact from the hurricanes?

Study Site and Demographics

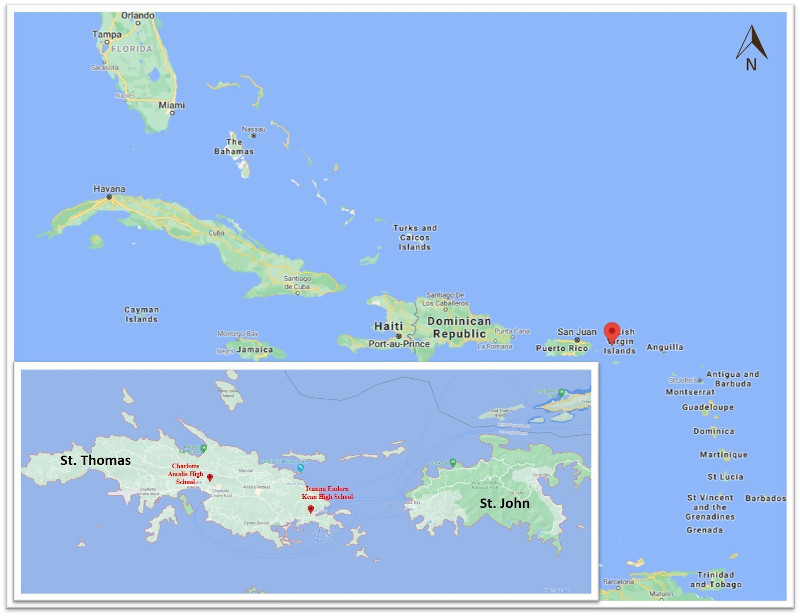

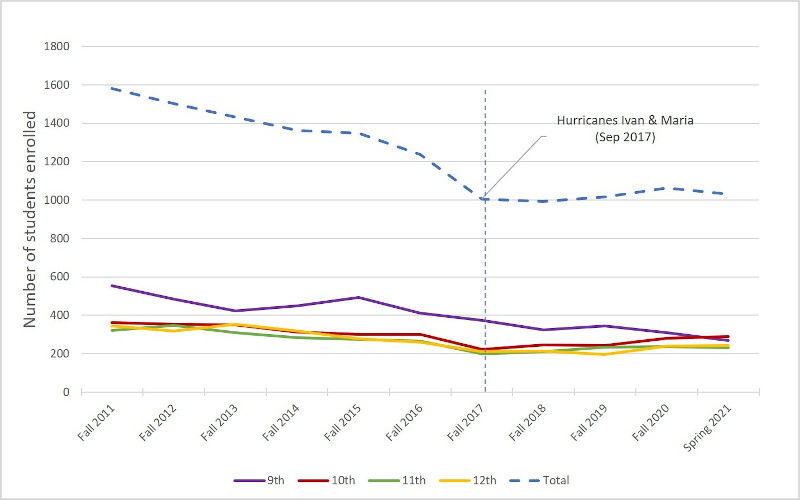

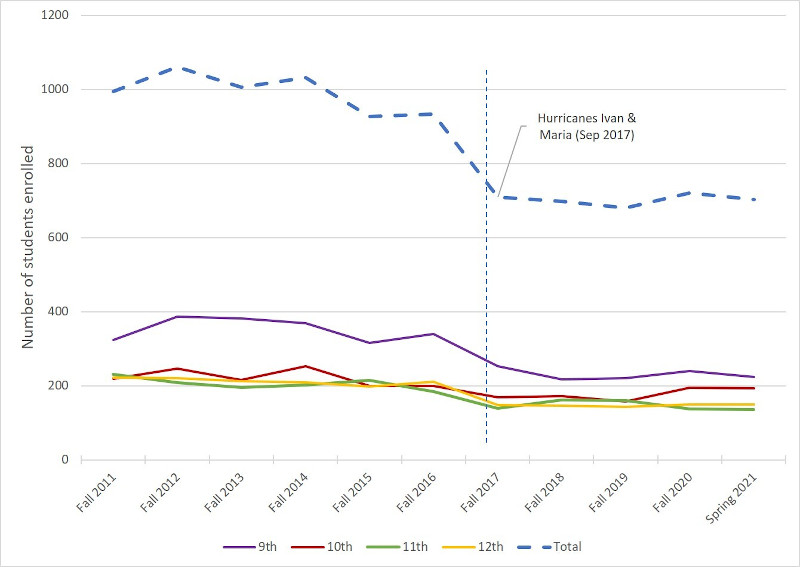

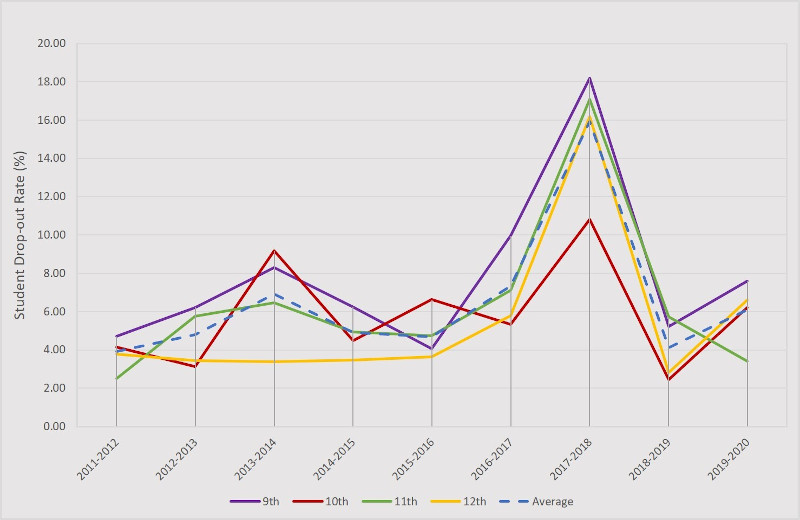

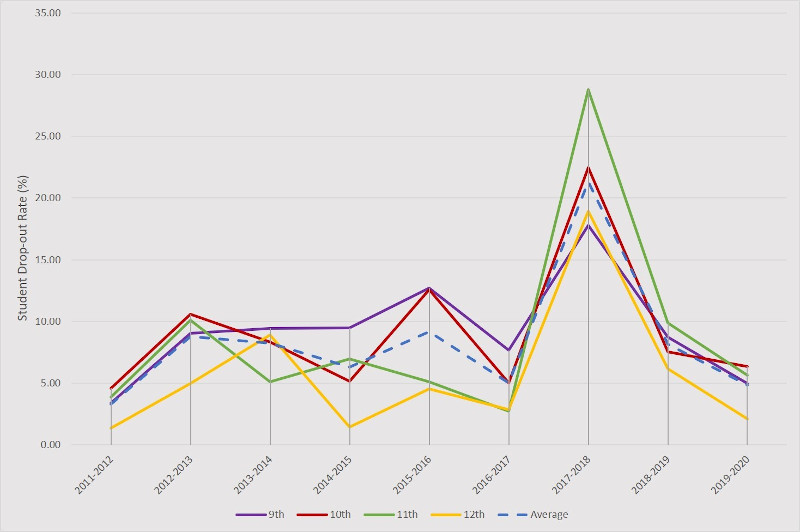

Participants for the study were recruited from two public high schools in the St. Thomas-St. John School district on the island of St. Thomas in the United States Virgin Islands (Figure 1). Charlotte Amalie High School is in an urban setting, while Ivanna Eudora Kean high school is in a semi-rural environment. Ivanna Eudora Kean accommodates high schoolers from St. Thomas in addition to those residing in St. John (there is no public high school in St. John). These high schools cater to students in grades 9–12, typically ranging in age from 14–18 who have completed elementary school (grades 1–5) and middle school (grades 6–8). Juniors and seniors in U.S. high schools typically range in age from 16–18 years. The student population at the two high schools were 80% to 90% Black and 9% to16% were Hispanic or Latino. There was an almost even split between male and female genders. In the past decade, both schools faced similar declines in student enrollment (see Figures 2 & 3) and trends in drop-out rates (see Figures 4 & 5). These rates were exacerbated following Hurricanes Irma and Maria due to emigration of impacted students (Figures 2 & 5).

Figure 2. Student Enrollment by Grade Level for Charlotte Amalie High School. Adapted from the Virgin Islands Virtual Information System (VIVIS B20). Virgin Islands Department of Education, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. May 15, 2021. URL: https//vivisdata.vi.gov.

Figure 3. Student Enrollment by Grade Level for Ivanna Eudora Kean High School. Adapted from the Virgin Islands Virtual Information System (VIVIS B20). Virgin Islands Department of Education, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. May 15, 2021. URL: https//vivisdata.vi.gov.

Figure 4. Drop-Out Rates by Grade Level for Charlotte Amalie High School. Adapted from the Virgin Islands Virtual Information System (VIVIS B20). Virgin Islands Department of Education, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. May 15, 2021. URL: https//vivisdata.vi.gov.

Figure 5. Drop-Out Rates by Grade Level for Ivanna Eudora Kean High School. Adapted from the Virgin Islands Virtual Information System (VIVIS B20). Virgin Islands Department of Education, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. May 15, 2021. URL: https//vivisdata.vi.gov.

Sampling and Recruitment

Schools were operating in a virtual learning environment due to the COVID-19 pandemic. There were no regular in-person classes during the time period when we conducted this study. The data collection protocol was approved by the University of Phoenix Institutional Review Board and Virgin Islands Department of Education. Data collection occurred from February 5 to May 31, 2021.

Teacher Recruitment

Teachers were recruited in February, 2021 through direct advertising sent by school principals to all teachers and staff via the teacher email distribution list. Any current high school teacher was eligible to participate because they may have mentored and aided students in coping with the hurricanes. The first page of the survey was the consent form that teachers had to agree to so that they could participate in the survey.

Student Recruitment

We first recruited students by emailing consent requests to parents. School principals were reluctant to share student contact information due to the possibility of survey burnout from other ongoing research programs. Our on-island assistant periodically delivered paper copies of the recruitment information to school staff for them to hand out to students. Toward the end of March, 2021 after schools had completed their surveys, one school shared parent and student email addresses. In April, 2021, we derived a list of student email addresses for the other school from the school’s public-facing Facebook page, and then we used the school’s student email directory to match contact information. Recruitment information including an assent form was sent directly to students via email. Once students agreed and provided reliable parent contact information, we sent parents an individualized DocuSign consent form. Once parental consent was obtained, we gave students a link and passcode to complete the online survey.

Student sample

Sixty-six students completed the online survey: mean age 17.06± 0.73 years, 63.6% female, 66.6% semi-urban/rural school setting, 68.2% 12th grade (Table 1). Of these, 28 students provided contact information and agreed to the follow-up interview, but after multiple attempts to reach them by text, phone, and email we only interviewed three students.

Teacher sample

A sample of 38 high school teachers and staff (63.2% from Charlotte Amalie High school and 36.8% from Ivanna Eudora Kean High School) participated in this study (see Table 2). The mean age group of 45–¬54 years, ages were in the 25–65 years or older range, and 65.8% were female. The sample population predominantly identified as Black or African American (73.7%), 28.9% were single or never married, 44.7% married, and 26.3% divorced. Of the sample, 65.8% had a graduate or professional degree and 28.9% had a college degree. We interviewed seven teachers who agreed and provided contact information for the follow-up Zoom interview.

Assessment

The following widely used screening scales were used to assess the well-being, coping skills, risk resilience, and post-traumatic stress disorder of both the adolescent students and adult teachers with authorization from the instrument owners where required:

- Mini Brief Risk-Resilience Index for Screening (BRISC) (Science of Behavioral Change (SOBC), 202021): We used BRISC to assess respondents abilities to regulate their emotions using a 15-item measurement. These included core measures of risk for experiencing emotional states such as (a) negativity bias (e.g. “I tended to overreact to situations”) and coping responses, (b) emotional resilience, (e.g. “I felt very satisfied with the way I look and act”), and (c) social skills, (e.g. “I enjoyed socializing and chatting to other people”). The answers for each category were summed and converted to standardized z-scores for comparison. This helped us to identify individuals who reported poor emotion regulation as well as those with good emotional health and coping. Emotional resilience and social skills serve as regulatory responses to the negative emotional state. BRISC scores ranged from 2–8.

- Brief Cope (Yusoff, Low, & Yip, 2010): We used Brief Cope to assess the coping strategies of adolescent and adult respondents. This NIH Toolbox instrument is widely used in research and has reliability (Cronbach's alpha) coefficients rating from 0.50 to 0.90.

- Child PTSD Screening Scale (CPSS) (Foa et al., 200122) and PTSD Screening Scale: We used these measures to assess the presence and frequency post-traumatic stress symptoms relating to the Hurricanes Irma and Maria in the previous month. Only Part 1 of this instrument (17 items) was used to examine the psychosocial problems that students were still experiencing (such as anxiety disorders or overreacting when startled). Three subscales were also assessed: re-experiencing (Items 1-5); avoidance (Items 6-12), and hyperarousal (Items 13-17), which occurs when a person suddenly becomes highly alert when thinking of the trauma from the disaster (e.g. sleeping problems, anger outbursts, etc.). A Likert scale ranging in value from 0 (not at all) to 3 (five or more times a week/almost always) was calculated to provide the subscale values and the overall CPSS score. A score of 12 or greater was classified as symptomatic for PTSD. A chi-square test for independence was computed to assess the association between PTSD and other factors such as grade, sex, dislocation, school type, etc. This instrument is widely used in research with reliability (Cronbach's alpha) coefficients ranging from 0.73 to 0.81.

Data, Methods and Procedures

Participating students and teachers took 20–25 minutes to complete a separate online survey using Survey Monkey. After the survey was completed, we sent emails and text messages to participants who had consented to do the semi-structured online interviews. Interviews were conducted and recorded using Zoom with the consent of the participants and lasted 30–45 minutes. We developed a schedule of guided questions and used for clarification and finding deeper insights into participant reasoning and perspectives. At the outset, the procedures for data handling, storage, and maintaining security and confidentiality were described to the interviewees. Once recorded, the audio portion was imported and transcribed using Otter.ai before being manually verified and edited. The names of respondents were coded as TE101, TE102 and so on to protect their identities. We read, re-read, and read aloud, and edited transcripts against the voice recording for clarity and consistency. We identified emergent themes. Keywords describing interviewee’s experience like “traumatic” and “difficult” were highlighted and their contexts provided useful summaries and direct quotes for analyses.

If the number of respondents were adequate, we conducted simple correlation and regression analyses, and chi-square tests for independence. The inadequate number of responses on some questions and lower than expected participation overall left us with no option but to do mostly descriptive analyses. We performed frequencies and cross-tabulations to assess the proportional association of the data.

Ethical Considerations

Each school and the district superintendent recommended or agreed to the study, which was then permitted by the Commissioner of the Virgin Islands Department of Education (VIDE). Respondents who consented to an interview, provided email addresses, and or phone numbers were contacted by phone, email, or text. Once their participation was confirmed, we sent a Zoom link to the respondents and scheduled an interview. Respondents were also reminded that the interview was voluntary, and that they could discontinue their participation at any time during the process. They were also reminded how the data would be used and that their responses would only be identifiable by codes to keep their identities confidential.

Findings

The findings are divided into two parts: (1) High School Students and (2) High School Teachers. The findings from the survey and the themes from the semi-structured interviews are summarized in reference to PTSD, risk resilience, coping, and the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic:

High School Students

PTSD

Three years after Hurricanes Irma and Maria, 22% of students surveyed continue to show signs of post-traumatic stress from the events. More female students (30%) reported that they experience PTSD compared with male students (5.3%). We examined the three PTSD subscales and found that male students did not recently re-experience any post-event trauma, while 12.5% of female students did. No difference was seen across grade levels (Table 3). Noticeably, 5.3% of male students compared to 47.5% of female students expressed avoidance symptoms; and 15.8% of male students compared to 35.5% of female students expressed hyperarousal symptoms. Female students were more likely to experience avoidance symptoms compared to re-experiencing and hyperarousal while male students were more likely to experience hyperarousal symptoms (Table 3).

There was a significant correlation between students who had to relocate as a result of hurricanes and those who continue to experience overall PTSD [rs(59) = .325**, p = .014]. All three core PTSD subscales, re-experiencing (rs(59) = .409**, p = .001], avoidance (rs(59) = .409**, p = .002) and hyperarousal (rs(59) = .296*, p = .025), correlated significantly with students who had to relocate as a result of the hurricanes. However, there was no significant correlation between overall PTSD levels and students who experienced damage to their residence. Yet, students who experienced damage to their residence had significant correlation with two of the three PTSD subscales: re-experiencing (rs(59) = .384**, p = .003] and avoidance (rs(59) = .311*, p = .018), but not hyperarousal.

Two-thirds of the students (66.1%) experienced damage from at least one of the hurricanes. Slightly more students (29.6%) who sustained damage to their residence from both hurricanes had lingering PTSD compared with 25% of those who sustained damage from only one of the hurricanes and 11.1% of students who had no damage to their residences from either hurricanes (Table 4). A higher percentage of those who had damages from both hurricanes had lingering PTSD associated with two of the subscales compared to those who had damages from only one of the hurricanes: re-experiencing (14.3%, 8.3%) and avoidance (48.1%, 33.3%). The same percentage of students (33.3%) experienced lingering hyperarousal PTSD for damage from one or both hurricanes (Table 4).

While most students (89.8%, N=53) stated that the hurricanes did not cause any delay in their graduation schedule, 10.2% (N=6) stated that their graduation was delayed by at least one semester (Table 5). One student (1.7%) reported that their graduation was delayed by at least a year and was expected to graduate in 2023. One-third (two out of six) of students with delayed graduation dates has longer-term PTSD. Also, 27.1% of the students (N=16) stated that they were still bothered by the effects of hurricanes, and 72.9% (N=11) stated that they were no longer bothered by the effects. Lingering PTSD was reported by 43.8% of those who were still bothered by the effects of the hurricanes (Table 7).

Risk-Resilience

In examining the risk-resilience among students (N=57), students showed a mean negativity bias score or hypersensitivity to stress and negative expectations of 13.40 (±5.9) (Table 6). The average regulatory response scores (i.e. for emotional resilience and social skills (Wichers et al., 2007) were significantly higher than the negativity bias score which indicates good resilience (Table 6). Emotional resilience score or the propensity for improved mental functioning was 17.44 (±4.1) and the average social skills score or the capacity to look for support and engage socially was 16.40 (± 5.1).

Coping

Over time, students employed several coping techniques with acceptance (5.73), self-distraction (5.18), active coping (5.18), positive reframing (5), and religion (3.91) scoring among the top five strategies (Table 7). However, students who still experience PTSD had significantly higher scores for negative coping mechanisms compared to those students who were no longer experiencing PTSD: including self-blame (4 compared to 2.9), venting (4.2 compared to 2.7), behavioral disengagement (4.5 compared to 2.6) and denial (3.7 compared to 2.6). Religion scored roughly the same for students with or without PTSD (3.9 compared to 4), but humor was slightly higher among students who were not experiencing long-term PTSD compared to those who were (3.5 compared to 3) (Table 7).

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic

Fifty percent of students believed that the COVID-19 pandemic had a worse impact on their educational performance than the hurricanes. Only 19.6% stated that their educational performance improved under Covid-19 compared to the impact from the hurricanes (Table 8a). A substantial percentage of students (32.1%) stated that the COVID-19 pandemic worsened their ability to cope with the effects of the hurricane while only 8.9% indicated that it improved their coping (Table 8b). This was supported by a significant negative correlation between the increasing post-traumatic stress (CPSS) Z-scores and improved coping during the COVID-19 pandemic Z-scores: (rp(59)=-.329*) (see table 8c). Roughly one third of students felt that the COVID-19 pandemic worsened their thoughts (37.5%) and feelings (35.7%) from the hurricanes.

High School Teachers

PTSD

Of the 27 teachers who completed the full survey, 29.6% experienced lingering PTSD (Table 9). Unlike students, a higher percentage of male teachers (42.9%) compared to (25%) of female teachers faced lingering PTSD. Among male teachers,¬ avoidance was the most commonly reported type of PTSD from the PTSD subscale (37.5%) while hyperarousal was the most reported type among female teachers (28.6%). A higher percentage of never married teachers had lingering PTSD (40%) compared with teachers who were married or divorced (22.2%).

More than half of teachers (51.61%) stated that they were still bothered by the effects of the hurricane. One third of teachers (33.3% ) who suffered damages to their residences from the hurricanes experienced lingering PTSD. Also, 14.81% of teachers were still waiting for the hurricane damage to their homes to be repaired. One teacher said that she applied for assistance from a government program to fix her damaged home, but after three years she still has no timeline for when it will be repaired.

Similar to students, PTSD was highest among teachers who had to relocate due to damage from the hurricanes (40%) compared to those who did not have to relocate because of the hurricanes (20%) (see Table 10). Twice as many of those who relocated compared to those who didn’t have to relocate experienced the re-experiencing type of PTSD (20% compared to 10.5%) and avoidance PTSD (30% compared to 15.8%). The difference was highest for the hyperarousal type of PTSD (50% for those who relocted compated to 15% for those who did not have to relocate).

Risk-Resilience

The mean negativity bias or hypersensitivity to stress and negative expectations score among teachers (Table 11) was 11.57 (±4.95), which was lower than student score. The average emotional resilience or the propensity to have improved mental functioning score (17.00±3.58) and social skills or the capacity to look for support and engage socially score (18.37±5.2) were higher than for students. This indicates that teachers were more resilient than students, which may be a product of maturity and experience (Wichers et al., 2007). Throughout the interviews, teachers emphasized the need to provide support to students before teachers.

Coping

Teachers used several strategies to help their students cope with the aftermath of the Hurricanes Irma and Maria. They provided opportunities for students to talk and write about their experiences. They relaxed school rules and adjusted the curriculum and instruction strategies. At a general assembly, students were encouraged to talk about their experiences, and they were invited to visit the counselor if they needed help (TE101). Expert interventionists were available for at least five months after the hurricanes. “We had meetings...we had psychologists, the psychiatrist, all of that came in, and then we gave them an opportunity to speak about how they were feeling” (TE105).

Students were invited to write about their experiences and feelings using the sensory writing approach to describe what they heard, saw, and felt. One teacher revealed “I had them do a lot of writing even though it’s a math class...I gave them the right to express themselves...I told them to sing, if they had a song they wanted to hear to ease their minds. We had to do all that.” (TE103).

Immediately following the reopening of schools in November 2017, the disaster response was focussed on helping students cope with the disruptions caused by the hurricanes. According to the teachers surveyed, instructional methods were adjusted to accommodate interruptions such as students asking to talk and write about the disaster. Many teachers had put their curricula, lessons, and supporting information online to make it possible to continue teaching. Some teachers had difficulties returning to their normal classroom routines because they had to wait for an order of replacement text books to arrive.

These disruptions resulted in lost instructional time. Teachers indicated that they could not make up for lost time, but they could use a scaffolding strategy that starts from where students are, then scaffolds the lesson. In scaffolding a teacher provides students with academic support until the lesson is learned. Teachers use strategies like audio-visual aids, think alouds, modelling, and breaking up lessions into chunks.

Teachers also employed coping strategies to help them personally overcome hurricane-related stresses (see Table 12). Unlike students, religion was the most reported coping strategy used by teachers. Teachers also planned and prepared. One teacher enrolled in a FEMA course on building resiliency to equip herself to support students. Both schools also encouraged peer counseling, teacher counseling, and had social workers check in with students weekly for five months.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic

Similar to students, more than one third of teachers (37.5%) stated that the COVID-19 pandemic made coping with the ongoing effects of the hurricanes worse. Only 16.6% of teachers felt that it improved their coping abilities (Table 13).

Other Findings

Respondents believed that as bad as their individual situations might have been others fared far worse. This mindset reflects Mayer & Kunreuther (2017) thesis of why people under prepare for disasters. They propose that, “people believe that others, not they, will fare worse.”

Respondents also described hurricanes as “the great equalizer” (TE102). The widespread destruction, the long lines, the universal disruptions seemed to have removed status differences and created a “common experience.” This common experience brought people together to assist each other, share resources, and provide support.

Finally, the respondents characterized their hurricane experience as an "act of God” and therefore beyond their control (TE105, TE101, TE104). Many discussed praying during the disaster for God’s help. They have also relied on prayers and religious beliefs as a primary coping mechanism in the long term.

Our study revealed that Hurricane Irma displaced about 200 students in one high school. Teachers could only guess where they were. Some may have migrated to the U.S. mainland, other Caribbean islands, or simply dropped out. School buildings were damaged, consolidated, and key facilities were used as housing. Teachers tried to maintain a semblance of normalcy by ensuring that important programs and events were held, however, learning what happened to displaced students is crucial for their educational outcomes and for establishing a community of care and compassion that can help them cope with lingering disaster effects.

Discussion

Our evidence showed that both students and teachers continue to suffer from the long-term mental and emotional effects of the hurricanes and these were further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. This series of disasters revealed the number of students and teachers who had lingering PTSD. Both students and teachers expressed that a third disaster, the COVID-19 pandemic, though three years later, worsened their ability to cope with damage caused by the hurricanes. While there was evidence that school-based support was provided to help students overcome PTSD, there is a need for ongoing mental health check-ins to extend beyond five or six months into the years following cascading disasters (Cutter, 201823; Michael et al., 2019; Lai et al., 2016).

Our analysis supported existing findings that female students were more likely to have lingering, long-term effects from cascading disasters than male students. The tendency of younger males to not self-report may obscure the true extent of PTSD among male students. However, the maturity of male teachers may lead to better self-reporting as adult male teachers expressed higher levels of PTSD than their female counterparts. The underlying factor of who self-reports may ultimately affect who receives and who needs assistance to recover from the recurring trauma. A broader systematic approach to facilitate self-reporting may be needed. One teacher said that students may be reluctant to talk to certified counselors but may do so with people they trust such as their music teacher.

Coping, Risk, and Resilience

Study participants appear to understand hurricane-related threats and their risks. They have employed coping strategies and regulatory response mechanisms to overcome stresses. Both teachers and students have developed enough resilience to overcome negative stresses overtime, but some may take hurricane damage for granted and just wait to move on to the next hurricane. However, in the case of the two cascading hurricanes, many expressed being overwhelmed and relied heavily on their resilience and positive coping mechanisms such as acceptance, religious faith, and positive reframing rather than negative ones such as substance abuse. These personal efforts could be complemented with reliable recovery support from non-profit organizations and government agencies.

Our results show that both students and teachers may have experienced similar levels of sensitivity to stress and coping, but teachers’ maturity may explain their ability to seek support and help. One teacher underwent FEMA training on how to cope with disasters and assist students. Such training may need to become mandatory for all teachers to improve their coping capacities and more broadly assist students.

Any study of hurricanes in the U.S. Virgin Islands and how residents cope must be discussed within the context of the frequency of these hurricanes in the Virgin Islands and the wider Caribbean. This was significant because residents including children were characterized as “hardy island people who are used to hurricanes” (TE102, TE105). “Sometimes, as island people, we do not like to be too touchy-feely about things, we kind of just toss it out and go on to the next thing” (TE102). This was a window into the mindset of people who have had frequent and chronic exposure to hurricanes and the challenge of adopting mainstream assessment and intervention strategies.

Alleviating or Helpful Measures

Teachers recognized the assistance that was given at the national level, through FEMA, and other humanitarian organizations including, food, water, clothing, school supplies, building repairs, and rent assistance, but some noted the need for more expert and targeted interventions. They believed that talking and writing helped studets cope with the hurricanes, but leaving the onus on students to seek counselling may not be the best approach. Discussing mental health or seeking psychological assistance is still taboo in the Caribbean.

Displacement, School Size and Educational Outlook

Displacement is more likely to happen during cascading disasters and lead to long term post-traumatic stress among more students and teachers. There is a general expectation that damage will occur during hurricanes especially as they become more frequent in the Caribbean, but students and teachers have not coped well with displacement. Lack of repairs on school buildings and homes after three years have contributed to the post traumatic stresses that students and teachers face. Classes were still being held in modular units and some students’ and teachers’ homes have not yet been repaired. More community and government support may be needed if students and teachers are to recover from the stresses of displacement and maintain educational performance.

Conclusions and Implications

Despite attempts to provide support for students in the aftermath of the hurricanes more than three years later, students still suffer from PTSD.

Key Findings

- Students in this study, particularly female students, still suffer from PTSD three years after Hurricanes Irma and Maria in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands.

- Cascading disasters amplified the lingering effects of the hurricanes especially for students and teachers who were displaced from their homes.

- Students believed that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their educational performance a lot worse compared with the impact from the hurricanes.

- The disaster is still ongoing after more than three years. Homes and buildings were still covered in temporary materials, modular buildings were still being used by schools and COVID-19 has only exacerbated the stresses related to the two hurricanes.

- Both teachers and students focused primarly on positive coping strategies, and stressed that structured pyschological assistance such as disaster-related counseling was available in the short term (less than 1 year) in their respective schools and community organizations, but became limited to personal efforts in the longer term.

Implications for Public Health Practice

This study shows that there is need for a “system of care” where teachers, parents, and other caregivers provide treatment and services to help both students and teachers recover from disasters faster (Adelman et al., 201224). Caregivers include community health organizations and government entities that provide services, resources, and training.

More expert evaluators need to be hired and engaged over a longer term to deal with the impact of disasters on students and teachers (TE101). Leaving it up to students to seek counseling and the practice of students talking and writing about their experiences were inadequate to address disaster effects on their mental health. Psychosocial-emotional intervention is required.

School Districts

A more systematic approach is required to assess PTSD among students in each school district who have experienced severe disasters. This approach should include the following:

- Schools should institute programs to evaluate student emotional health on an ongoing basis.

- School staff needs to be able to intervene with students to help reduce the chronic nature of post-disaster traumatic symptoms (Adelman et al., 2012).

- School must extend the time for both assessing student mental health after disasters to more than six months, and increase their capacity to prevent, identify, and ameliorate mental health problems.

- Capacity building for all teachers and staff (not just counselors) should include training in social skills, resilience, emotional intelligence, disaster recovery mentoring, and psychotherapy training.

Schools should also maintain the family-centered care that was implemented immediately after the disaster and return to school. This caring school culture may shorten the long-term stresses felt by students and teachers.

Parents

Parents need to work with students beyond just accepting what has happened and provide support, positive reinforcement, and active coping. Children with lingering PTSD symptoms tend to give up trying (behavioral disengagement) or blame themselves more. They need more support from parents to overcome stressors.

Community Health & Disaster Recovery Organization

Community and health organizations should develop instruments to facilitate assessment of mental health in schools in the long term and provide psychological care to students because—as this study indicates—roughly one in five students continue to have PTSD.

Disaster recovery organizations should also prioritize health assistance for the students and teachers who suffer loss and dislocation from disasters and tend to experience PTSD longer than others.

Government

After cascading disasters government agencies should prioritize helping displaced families. Displacement is among the biggest drivers of long-term PTSD. Government agencies should distribute resources to students and teachers who are displaced so that they can return to their homes sooner.

Disaster recovery plans and policy documents should also include children’s perspectives on how to best cope with and recover from disasters. The plans should incorporate long term psychological health programs for children displaced by disasters, which may require additional facilities, support, and training for school staff.

Dissemination of Findings

The findings and recommendations from the study will be disseminated in two presentations to the St. Thomas-St. John School District, participating high schools, and their affiliated stakeholders in September 2021. This will occur onsite unless there are unforeseen travel restrictions that would require us to make virtual presentations. After the presentations, we will write journal articles for peer review and publication.

Limitations

Because classes were being conducted online, the task of recruiting students was done remotely and through district and school officials, which made the process more protracted and difficult than usual. We provided incentives to increase participation with some success. COVID-19 restrictions made locating and communicating with respondents challenging, and interview scripts were not sent to respondents for their review. This practice, called “member checking,” improves the validity of qualitative research (Creswell & Poth, 2018[^Creswell & Poth, 2018]).

Requests for the academic performance data were not fulfilled because standard testing has been irregular in the past five years. Administrators were reluctant to release individual standard test results because of ethical concerns. This made conducting regression analyses on academic performance statistically irrelevant. In addition, the prolonged effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, student displacement, and online learning were confounding factors that could not be isolated to make valid conclusions about the impact of cascading disasters on the academic performance of students.

Future Research Directions

More studies are needed to continue to assess the strategies that best address PTSD in the long term after cascading disasters. A comparative study of parents and high school student reactions to disasters can help validate responses and determine what actions should be taken to create a system of care. Additional research should also be conducted to determine which institutional post-disaster programs and school counseling programs are most effective at eliminating long term stresses from cascading disasters. Studies with larger sample sizes need to be done to determine the long-term effect of cascading disasters on student educational performance.

Acknowledgements. This study was conducted with support from Quick Response Program funding from the National Science Foundation, administered by the Natural Hazards Center at University of Colorado, Boulder. We kindly acknowledge the Virgin Islands Department of Education, the St. Thomas -St. John School District, Charlotte Amalie High School, and Ivanna Eudora Kean High School for supporting and facilitating this study. Special thanks to our on-island assistant, Morella Dore, who spoke with school principals to get site permission for this study and to distribute paper copies of the recruitment forms to schools.

References

-

Virgin Islands Department of Education, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. Virgin Islands Virtual Information System (VIVIS B20). May 15, 2021. URL: https//vivisdata.vi.gov. ↩

-

Michael, N., Valmond, J. M., Ragster, L. E., Brown, D. E., & Callwood, G. B. (2019). Community needs assessment: Understanding the needs of vulnerable children and families in the US Virgin Islands Post Hurricanes Irma and Maria. St. Thomas, USVI: Caribbean Exploratory Research Center, School of Nursing, University of the Virgin Islands. ↩

-

Wasonga, T., Christman, D., & Kilmer, L. (2003). Ethnicity, Gender and Age: Predicting Resilience and Academic Achievement among Urban High School Students. American Secondary Education, 32(1), 62-74. Retrieved September 20, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41064505. ↩

-

Fothergill, Alice. 2017. Children, Youth, and Disaster. Natural Hazard Science, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.23. ↩

-

Peek, L. (2008). Children and disasters: Understanding vulnerability, developing capacities, and promoting resilience—An introduction. Children Youth and Environments, 18(1), 1-29. ↩

-

Silverman, W. K. and La Greca, A. M. (2002). Children Experiencing Disasters: Definitions, Reactions, and Predictors of Outcomes. In La Greca, A.M.,W.K. Silverman, E.M. Vernberg, and M.C. Roberts, eds. Helping Children Cope with Disasters and Terrorism. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 11-33 ↩

-

Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., Watson, P. J., Byrne, C. M., Diaz, E., & Kaniasty, K. (2002). 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981-2001. Psychiatry, 65(3), 207–239. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173 ↩

-

Anderson, W. A. (2005). Bringing children into focus on the social science disaster research agenda. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 23(3), 159. ↩

-

Lai, B. S., Esnard, A. M., Lowe, S. R., & Peek, L. (2016). “Schools and Disasters: Safety and Mental Health Assessment and Interventions for Children.” Current Psychiatry Reports 18(12): 1-9. ↩

-

Peek, L., & Richardson, K. (2010). In their own words: Displaced children's educational recovery needs after hurricane Katrina. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 4(3), S63-S70. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/dmp.2010.10060910 ↩

-

Lazarus, R.S. & Folkman, S, (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Oxford University Press ↩

-

Feinauer, L., Middleton, K. C. & Hilton, G. H. (2003). Existential well-being as a factor in the adjustment of adults sexually abused as children. American Journal of Family Therapy, 31(3), 201-213. ↩

-

Aja, A., Lefebvre, S., Darity Jr., W., Ortiz-Minaya, R., & Hamilton, D. (2018). Bold polices for Puerto Rico: a blueprint for transformative, justice-centered recovery. The Nation, Residente, Calle 13, Interview. ↩

-

Gilbert, E. (2019, August 6). C.A.H.S. to be heavily restricted or altogether condemned for 2019-2020 school year. The Virgin Islands Consortium. URL: https://viconsortium.com/VIC/?p=77110. ↩

-

Serrant, T. D. (2013). How does the government of Dominica address education during chronic low-intensity hurricanes, Ph.D. Dissertation: University of Pittsburgh. ↩

-

United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). (2020). Social determinants of health. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health/. ↩

-

Mooney, Maureen, Ruth Tarrant, Douglas Paton, David Johnton, and Sarb Johhal. 2020. “The School Community Contributes to How Children Cope Effectively with Disaster.” Pastoral Care in Education 39(1): 24-47. ↩

-

Hobfoll S.E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology. 2002;6(4):307-324. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307 ↩

-

Pan American Health Organization. (2018). CDB and PAHO sign agreement to support mental health in aftermath of natural disasters. PAHO Caribbean Subregional Program Coordination. https://www.paho.org/spc-crb/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=522:cdb-and-paho-sign-agreement-to-support-mental-health-in-aftermath-of-natural-disasters&Itemid=1540. ↩

-

Eder, D. & Fingerson, L. (2002). Interviewing children and adolescents. In Gubrium, J.F. and J.A. Holstein, eds. Handbook of Interview Research (181-201). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. ↩

-

Science of Behavior Change (2020). Mini Brief Risk-Resilience Index for Screening (BRSIC). URL: https://scienceofbehaviorchange.org/measures/brief-risk-resilience-index-for-screening-brisc/. ↩

-

Foa, E. B., Johnson, K. M., Feeny, M., & Treadwell, K. R. (2001). The child PTSD Symptom Scale. A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical /Child Psychology, 30(3), 376-384. ↩

-

Cutter, Susan L. 2018. “Compound, Cascading, or Complex Disasters: What’s in a Name? Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 60(6): 16-25. ↩

-

Adelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2012). Mental health in schools: Moving in new directions. Contemporary School Psychology, 16(1), 9-18. ↩

Huggins, L., & Serrant T. (2021). Exploring the Long-Term Impact of Cascading Disasters in the U.S. Virgin Islands on High School Student and Teacher Mental Health and Resilience (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 10). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/exploring-the-long-term-impact-of-cascading-disasters-in-the-u-s-virgin-islands