Frontline Government Workers

Assessing Post-Disaster Burnout and Quality of Life

Publication Date: 2021

Executive Summary

Overview

The impact of disasters on the United States Virgin Islands (USVI) has been significant in recent years. In September 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria severely damaged infrastructure including roads, hospitals, seaports, airports, businesses, housing, and schools. Followed in 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic, the USVI faced additional challenges to its public health and economy. Tourism is a major source of revenue and hotels, cruise ships, tourist attractions, restaurants, and transportation services all suffered severe economic losses. COVID-19 also threatened the health and safety of the population of the USVI many of whom were among society’s most vulnerable. To understand the impact of increased reliance on government services during disasters, this study examined frontline workers from various government agencies in the USVI. Frontline government workers were defined as public sector personnel who have a direct role in providing services to citizens. These groups endure additional stresses during a disaster making the psychological well-being of frontline government workers is a critical concern during any disaster. Our research examined the relationship between burnout and frontline workers’ professional quality of life. We defined burnout as a state of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduction of personal accomplishment. Professional quality of life (ProQol) encompasses positive (compassion satisfaction) and negative (compassion fatigue) views of work conditions.

Research Design

We gathered empirical evidence using a quantitative and qualitative research design. We used email to recruit participants who were employed in one of nine government agencies and departments by inviting them to complete our online survey. The survey contained demographic questions, a modified version of the Professional Quality of Life Scale, and Maslach Burnout Inventory. The preliminary data analysis was based on a sample size of 112 responses. Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. Paired Sample t-test, factor score correlation, and thematic content analyses were employed to examine the research questions.

Research Questions

The research questions that guided the data analysis were: (a) Was there a difference between burnout and professional quality of life experienced by frontline government workers in the USVI during Hurricanes Irma and Maria and COVID-19? (b) Was there a relationship between burnout and the professional quality of life experienced by frontline government workers in the USVI during Hurricanes Irma and Maria and COVID-19? (c) Considering post-disaster job experiences, what measures do frontline workers feel could have been implemented to reduce burnout or improve quality of life?

Implications and Conclusion

Our preliminary analysis uncovered a significant difference between frontline worker experiences of burnout during Hurricane Irma, Hurricane Maria, and COVID-19. Additionally, there were various relationships between the subscales of burnout and quality of life for frontline government workers following Hurricanes Irma and Maria, as well as during COVID-19. Specifically, emotional exhaustion and compassion fatigue were at the core of psychological challenges faced by USVI frontline government workers during disasters. However, organizational activities that support emotional well-being, personal accomplishment, and compassion satisfaction can be used to reduce work-related burnout within disasters. They also increase psychological resilience of frontline government workers and governmental services.

Introduction

In the face of disasters, societies turn to frontline government workers to ensure that public services are available. After Hurricanes Irma and Maria devastated the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) within a two-week timeframe in 2017, residents had to rely on public personnel from an array of government agencies. As COVID-19 surfaced, these frontline employees were again required to keep the adversely affected population safe. Within the past few decades, earthquakes, tornadoes, floods, tsunamis, wildfires, volcanic eruptions, hurricanes, and other biohazards (such as COVID-19) have increased (Low, 20131; Trenberth, 20052; Bertz, 19913). Due to its location in the northeastern Caribbean, the territory is in the path of many tropical weather systems and hurricanes. The USVI is also more vulnerable to earthquakes and tsunamis because it is located near a fault in the Earth’s tectonic plates (U. S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet, 20014).

On September 6, 2017, Hurricane Irma made landfall on St. Thomas and St. John, wind gusts of up to 165 miles per hour caused catastrophic devastation. Disaster struck again on September 17, 2017, when Hurricane Maria destroyed most of the island of St. Croix with wind gusts reaching up to 172 miles per hour (USVI Hurricane Recovery & Resilience Taskforce, 20175). These disasters caused loss of life and property, stress, anxiety, depression, feelings of hopelessness, and psychosocial problems for the residents of the USVI (World Health Organization, 20136). There were, however, vulnerable groups that required additional attention. These groups included the elderly, individuals with disabilities, children, women, the poor, and prisoners (Hoffman, 20097). Frontline workers were equally at risk based on their presence, participation, and experience in disasters. We define frontline government workers as public sector personnel who have a direct role in providing services to citizens. Although frontline workers were expected to respond whenever a disaster occurs, concern for their well-being was often disregarded. These individuals encounter loss of property, life, illnesses, familial responsibilities, and emotional issues in the same way as the rest of the community (Hope, 20108). For this study we selected nine government agencies whose employees played a significant role in responding to Hurricanes Irma and Maria, and COVID-19 (See Table 1). Although the focus in a disaster is generally on the well-being of the society as a whole, the needs of employees at the frontlines require more attention. This study assesses the level of burnout and the quality of professional life of frontline government workers in the USVI.

Literature Review

Stages of Disasters

Xiao, Huang, and Wu (20159) identified five phases of a natural disaster timeline: (1) prevention, preparedness, and mitigation; (2) watches and warning; (3) impact; (4) response; and (5) recovery. In all phases of disasters, local teams, including frontline workers, perform tasks prior to the disaster and continue until well after it has ended. Participation in all aspects of a disaster was a cause of burnout and affected quality of life among frontline workers. To ensure preparedness during the early stages of a disaster, emergency teams must identify and make employees aware of all responsibilities, risks, and vulnerabilities that may occur (Jaiswal & Shejy 201710). Jaiswal and Shejy (2017) also state that disaster recovery plans should go beyond physical responses to include emotional care for employees. Nevertheless, frontline workers may push themselves beyond their limits during the response stage and become most likely to quickly burnout unless given a lengthy recovery period. Similarly, Wu, Connors, and Everly (202011) noted that frontline workers, particularly those in health care, during the impact and response period were likely to be anxious about themselves or family members becoming exposed to infections, burnout, post-traumatic stress, and acute psychological distress.

Impact on Mental Health

Understanding how disasters impact the mental and psychological well-being of survivors is a key component of providing services that improve community resilience. This is even more important as it relates to frontline workers. Similar to the airplane oxygen mask rule, frontline workers must ensure that their own ‘oxygen masks’ are secured before they can assist others. Frontline workers operate as survivors of disasters. They are service providers for co-survivors. At times of disaster, frontline employees may have to manage life during shortages of water, electricity, phone, and internet services, which reduces their ability to effectively complete routine tasks (Nygaard & Heir, 201212). Yuma et al. (201913) contended that frontline workers in social and healthcare services experience substantial levels of stress in response to disasters. These stressors remain in play during the recovery process. Raj and Sekar (201414) noted that an exposure to distressing stimuli and the demands of work can lead to emotional and mental pressures in any group of frontline personnel.

As communities recovered, frontline workers played a major role in the rehabilitation, relief, and restoration of devastated areas. They continued to provide for the needs and services of the public, often discounting their own challenges, needs, and interests. Unfortunately, few support options were available for their psychosocial and overall well-being. Matsuo et al. (202015) noted that problems of burnout among health care workers overlap with symptoms of depression. These work pressures continue to be a critical concern that has not gained enough attention. The lack of research on approaches to support the needs of frontline workers compounds the problem (Yuma et al., 2019).

While providing support for disaster affected populations, frontline workers must also maintain their personal, familial, and professional obligations (Raj & Sekar, 2014, p. 26). During a disaster, frontline workers must work longer hours, handle heavier workloads, and respond more rapidly to difficult situations despite a harsher environment. Disasters may leave areas without power, telecommunications, and its citizens could be under curfews. Still, employees find alternatives to complete necessary tasks. During the COVID-19 pandemic, frontline workers assisted people with physical and emotional problems that increased their own risk of infection while also having to manage their own mental and emotional distresses (Banerjee et al., 2020). Burnett and Wahl (201516) brought attention to the way that frontline workers job responsibilities led to them experiencing continuous indirect trauma. We define indirect trauma as negative consequences resulting from working in hazardous or unsafe work environments and with survivors of traumatic experiences. Ongoing exposure to direct and indirect trauma can result in burnout (Tarshis & Baird, 201917).

Burnout and Employee Well-Being

Burnout occurs due to workplace stress that has not been successfully managed (World Health Organization, 201918). It was categorized by three factors: (1) feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion, (2) increased mental distance from one’s job or feelings of negativity or cynicism related to one’s job, and (3) reduced professional efficacy. It is easy to overlook burnout during times of disasters. Fujitani et al. (201619) observed that the initial worldwide media attention and adrenaline rush following a major disaster may bury the initial burnout faced by frontline workers. Overtime, deterioration could become critical once frontline workers begin to exhibit burnout. The effect on a community, the disaster response organization, and the individual requires a proactive solution rather than a reactive response.

Hall et al. (201020) noted psychological and physiological problems in police officers with increased job demands. Some officers struggled with burnout, marital problems, heart disease, and suicide. The high-stress role of police officers and other frontline workers also has an influence on work-family balance. Although residents turned to police officers to assist them when they were most vulnerable, high-stress situations exacerbate crisis reactions by officers. Piotrkowski and Telesco (201121) looked at the well-being of disaster workers and first responders following the World Trade Center attacks in 2001. During the attacks, officers worked longer shifts and worked with traumatized victims. Emotional exhaustion and limited recuperation time have been related to symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among disaster workers at the World Trade Center (Piotrkowski & Telesco, 2011). Similar to police officers, emotional exhaustion has been studied in nurses and social workers. Manzano Garcia and Ayala Calvo (201122) acknowledged that emotional exhaustion was one key factor to affecting the overall quality of care that nurses give to their patients. During the Covid-19 pandemic Chen et al. (202123) found that emotional exhaustion and burnout can diminish the quality of service and care delivered by nurses. As the amount of care disaster victims require increases, so do burnout levels among frontline disaster workers. Because employees care, they sacrifice more energy on the job than they should, making them exhausted and stressed.

For frontline workers to have a positive outlook on their jobs and lives, they must seek emotional and psychological assistance when they experience stress. Their ability to cope is particularly important in stressful situations. They should also be able to look to peers for social support. Though support from loved ones is undeniably important, peers offer understanding that other support systems may not be able to provide. Frontline workers also need to be able to avoid situations that trigger memories of traumatic experiences that often occur during disasters (Prati, Palestini & Pietrantoni, 200924).

Compassion satisfaction was described as the sum of all positive feelings a person develops through helping others (Sacco et al., 201525). Researchers have found that compassion satisfaction was instrumental in decreasing employee burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Kim & Lee, 201926; Conrad & Kellar-Guenther, 200627). Secondary traumatic stress is the condition where professionals face some form of trauma in their work experience. Similar to burnout, secondary traumatic stress can lead to job turnover and reduced productivity (Yadollahi et al., 201628).

Gaps in Literature

One critical concern that research has not addressed is the need for a broader view of who should be considered frontline personnel. Generally, the focus has been on police, firefighters, health care providers, and social workers. In a more comprehensive direction, Raj and Sekar (2014) labeled health workers, schoolteachers, governmental leaders, and others who have direct impact on affected communities in times of disaster as community level workers. Scholars must expand their research to include personnel from an array of service sector government agencies, who may also find themselves overwhelmed by citizens in need during disasters. Limited research looks to environmental health employees, 911 operators, employees of temporary housing, medical and food assistance, unemployment, and other governmental personnel who have more residents requesting services following disasters.

Despite the compounding circumstances of disasters in the USVI, very few studies analyzed the effects of disasters on frontline workers. These employees were essential in providing necessary services to remote locations. Researchers must look to these personnel to better understand how to endure multiple disasters.

Methods

Research Questions

The following research questions guided our data analysis:

- Was there a difference between burnout and professional quality of life experienced by frontline government workers in the USVI during Hurricanes Irma and Maria and COVID-19?

- Was there a relationship between burnout and frontline government workers’ professional quality of life during Hurricanes Irma and Maria and COVID-19?

- Considering post-disaster job experiences, what measures do frontline workers feel could have been implemented to reduce burnout or improve professional quality of life?

Study Site Description

This study examined nine agencies and departments (see Table 1) of the Government of the Virgin Islands. We chose these organizations because a considerable number of employees with these departments are frontline government workers including but not limited to nurses, police officers, firefighters, social workers, case managers.

Methods and Procedures

This study uses a mixed-method approach that includes quantitative and qualitative elements. The quantitative component consisted of demographic variables such as age, length of employment, marital status, ethnicity, gender, and level of education (see Table 2). We also included a modified Professional Quality of Life Scale and a modified Maslach Burnout Inventory. The online version of the questionnaire was created using the Qualtrics platform. Qualtrics is an online survey tool that allowed the investigators to design and distribute the survey as well as analyze responses.

The Professional Quality of Life Scale, Version 5 (ProQol) (Stamm, 201029), is a 30-item scale that measures the positive and negative effects of helping others. ProQol contains three subscales: compassion satisfaction (CS), compassion fatigue (CF), and burnout (BO). ProQol allowed respondents to rate their overall postdisaster professional experiences. Items were rated on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Stamm (2010) noted that ProQol has good to very strong internal reliability, which improves the chances that comparisons across versions will be acceptable. Stamm (2010) stated that ProQol has always had an alpha reliability between .84 and .90. Some indicators of good construct validity based on over 200 published papers and more than 100,000 articles on the Internet were reported.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) used a five-point rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often.) Schaufeli et al. (199630) noted that MBI measures three dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. Schaufeli et al. (1996) reported the following internal consistencies (Cronbach coefficient alphas): 0.87 to 0.89 for emotional exhaustion, 0.73 to 0.84 for depersonalization, and 0.76 to 0.84 for personal accomplishment. Test-retest reliabilities after one year were 0.65 (emotional exhaustion), 0.60 (depersonalization), and 0.67 (professional accomplishment). Schaufeli et al. (1996) noted the basic three-factor structure underlying burnout syndrome has been repeatedly confirmed by exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses.

The qualitative component consisted of three open-ended questions, which were asked on the survey. The data was analyzed using thematic content analysis, which determined the presence and relationship of concepts. Participant responses were grouped based on the questions. The responses for each question were read and assigned codes. Once the coding was completed, the data was examined to find patterns. The codes were counted to determine reoccurrences within participants’ responses. Similar and related codes were grouped and emerging themes were identified. These themes were illustrated in the findings and have the potential to answer questions about frontline government worker impressions and experiences with disasters. Key quotations were selected to showcase respondent perceptions.

Participants and Data

The authors first received Institutional Review Board approval from the University of the Virgin Islands on January 29, 2021 (Approval #1667715-3). We sent an email to the department heads or chief executive officers of nine governmental agencies requesting that their employees be allowed to participate in this study as well as access to their employee email lists. Upon approval, employees were recruited through an email invitation (see Table 1). The invitation included a description of the study, a link to the survey, and an electronic informed consent notice. Participants were required to give their informed consent in Qualtrics before starting the survey. The data used for this preliminary report were collected during a one-month period (February to March 2021) in two-week intervals.

During the first phase of the study, 131 responses were obtained, but 19 surveys had to be removed because they were incomplete or missing data. A total of 112 responses were received from the Department of Human Services (29%), VI Police Department (20%), VI Territorial Emergency Management Agency (19%), Department of Planning and Natural Resources (13%), VI Fire Service (7%), Department of Licensing and Consumer Affairs (5%), Bureau of Motor Vehicles (4%), and unidentified departments (3%). Women accounted for 74% of respondents, men comprised 17% of the sample, 9% did not report gender. The age distribution of survey respondents varied with 18–25 years at 4%, 26–35 years at 16%, 36–45 at 26%, 46–55 at 42%, and 56 or older was 13%. A total of 83% of respondents identified as “African American or Black,” 7% identified as “White,” 6% identified as “Latino or Hispanic,” and 4% chose “Other.” Level of education varied among survey respondents: 35% had an undergraduate college degree, 23% had completed some college, 22% had a master’s degree, 16% had a high school diploma, and 2% had a doctorate or professional degree, including juris doctorates, MD, or PhD. Only 1% noted having completed trade school, and 1% did not report. The marital status of participants showed 41% as single, 33% as married, 13% as divorced, 12% in a relationship but not married, and 2% did not report (See Table 2).

Preliminary Data Analysis

All quantitative statistical analyses were performed with IBM-Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM-SPSS) for Windows, version 27. Paired t-test and factor score correlation were used to examine the research questions. Paired sample t-tests were used to compare the difference between burnout experienced following Hurricanes Irma and Maria versus COVID-19. Paired-sample t-tests were used to determine the mean difference between two sets of observations, and to identify whether there is an alteration in a measurement as a result of conditions. The same test was also used to compare the difference in ProQol following Hurricanes Irma and Maria and COVID-19. The mean differences between measures were determined statistically significant at or below 0.05.

Correlation analysis was used to examine relationships between burnout and professional quality of life during Hurricanes Irma and Maria. We made associations based on the factor score of Maslach Burnout subscales (emotional exhaustion, personal accomplishment, and depersonalization) and ProQol subscales (burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction). A factor score is an amalgamation of variances resulting from the interrelationships of the factor loads. We also used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to create variables from factor scores for the subscales. As a rule, factor loadings were rotated twice. Factor loadings of at least an absolute value of 0.4 were considered important. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test was used to compare the magnitude of the correlation coefficients. A value of 0.5 or more was considered to provide sampling adequacy. Correlation measures the strength of linear relationship between two or more variables. The values of strengths range from -1 to +1. The closer the values were to the absolute value of 1, the stronger the relationship. We created variables for burnout and ProQol subscales based on factor scores. Hinkle et al. (200331) identified the following criteria to interpret the relational strengths of coefficients: 0.7 to 0.9 high correlation; 0.5 to 0.7 moderate correlation; 0.3 to 0.5 low correlation; and 0.0 to 0.3 little if any correlation.

Findings

Results

With this study we set out to examine frontline government worker burnout and quality of life following three recent disasters: Hurricanes Irma and Maria, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings were important because of the significant impact on local public health. Thirty percent of people working in the USVI were government employees (Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research, 202032). Many of them interact with the community on a daily basis.

The differences between burnout and ProQol experienced following Hurricanes Irma and Maria, and COVID-19 were explored based on paired sample t-tests and exploratory factor analysis. A paired sample t-test was used to compare the difference between burnout experienced following Hurricanes Irma and Maria versus COVID-19. Our results indicated that there was a significant difference in burnout experienced (t=1.76, p=0.04). Furthermore, we used a paired sample t-test to compare the difference between ProQol experienced following Hurricanes Irma and Maria and COVID-19. Our results indicated that there was not a significant difference in quality of life (t=0.31, p=0.75). Tables 3 and 4 present the correlation matrices of the associated factor scores for both burnout and ProQol subscales. Table 3 presents the correlation between burnout and ProQol subscales following Hurricanes Irma and Maria, and Table 4 presents the correlation between burnout and ProQol subscales during COVID-19. All subscales included in the matrices had a KMO above 0.5 indicating that their factor loadings and scores were representative of the subscales.

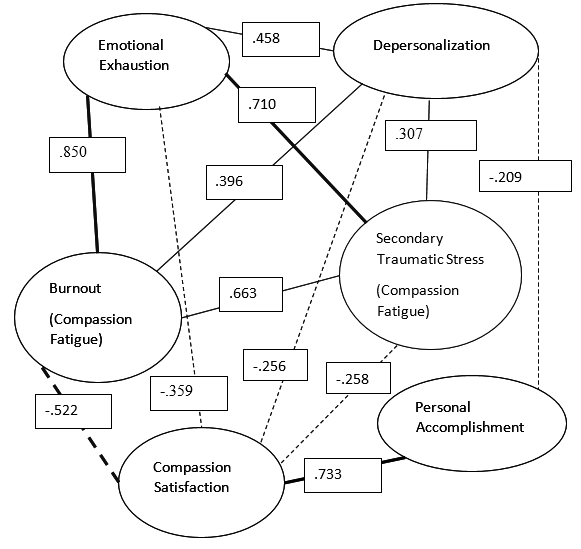

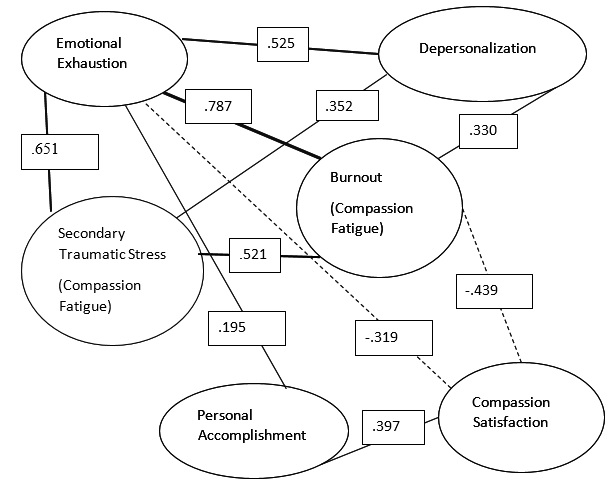

Table 3 presents the correlations found between the subscales of burnout and ProQol in the aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and Maria. The strongest correlation (.850) was observed between emotional exhaustion and burnout (components of compassion fatigue). We found high correlations between emotional exhaustion and secondary traumatic stress (.700), and burnout and secondary traumatic stress (.663). We also found high correlation (.733) between compassion satisfaction and personal accomplishment. Finally, our research revealed there was a moderate inverse correlation (-.522) between burnout and compassion satisfaction. Table 4 showed the correlations between burnout and ProQol during COVID-19. We saw the strongest correlation (.787) between emotional exhaustion and burnout. Moderate correlations exist among emotional exhaustion and secondary traumatic stress (.651), secondary traumatic stress and burnout (.521), and emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (.525). We found a low correlation between personal accomplishment and compassion satisfaction (.397). Lastly, we noted an inverse correlation between burnout and compassion satisfaction (-.439) and between emotional exhaustion and compassion satisfaction (-.319).

Emerging themes from our qualitative data provided insight into the opinions of frontline government workers. Table 5 provides an overview of the qualitative data. Although the researchers have condensed recurring commentary, the following quotes were among the most profound. Participants wrote the following comments:

Parents and grandparents are forced to choose between coming to work or risk losing their jobs because daycares and schools weren’t open. Supervisors without children or independent children were not amenable to [frontline workers] who have young children.

All persons working [during] COVID-19 were filled with anxiety about the unknown. Although most people [employees] are not willing to admit this, the government did very well from a supply perspective; however, the employee’s emotional sides were secondary. More attention is needed on the people on the front line.

Officers needed a call center set up where family members could go for assistance in making contact with the employee. While on duty, there is no way to know if family was safe. Also, food supplies should be provided since there is no opportunity, especially in the face of a hurricane, to purchase food or find anything to eat.

Discussion

The findings presented in Tables 3 and 4 were used to create Figures 1 and 2 respectively. Each figure offers models that characterize the relationships of burnout and ProQol among USVI frontline government workers in the aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and Maria and also during the COVID-19 pandemic. There were two models which showcased different associations of the subscales. The associations in Figure 1 were clearly stronger than the associations in Figure 2, so the analysis of burnout and ProQol following hurricanes may provide a greater representation of participating frontline government worker experiences. Emotional exhaustion and compassion fatigue (secondary traumatic stress and burnout) could also be considered core elements of USVI frontline government workers’ quality of life during disasters.

Figure 1. Model of USVI Burnout and ProQol based on Hurricanes Irma and Maria

Figure 2. Indirect Trauma of Frontline USVI Government Workers Model – COVID-19

Additional relational implications can be gained from examining Figures 1 and 2. The lines in Figures 1 and 2 represent the correlation coefficient strengths of associations ranging in values from +1 to -1. They also show moderate to low relationships between depersonalization and emotional exhaustion as well as compassion fatigue (secondary traumatic stress and burnout). Figures 1 and 2 also show varying relationships between personal accomplishment and compassion satisfaction. Our findings show that compassion satisfaction has a higher inverse relationship with burnout, as well as smaller inverse relationships with other elements of indirect trauma. Compassion satisfaction can be an influence in reducing the impact of indirect trauma on the frontline government workers in the USVI. Conversely, personal accomplishment shows a positive effect on compassion satisfaction. As noted in Table 5, and in line with findings above, the qualitative analysis for questions one and two yielded several emerging themes. Among them, more psychological and emotional support, more supplies, more compassion and understanding, and more time for family and rest were the things respondents asked for most. More than half of participants who responded to questions one and two (56% and 52% respectively) stressed the need for their agencies to provide supplies and/or increase their level of compassion, empathy, and understanding. Several participants mentioned a lack of understanding for participants with children receiving online instruction. About 16% of all participants responding to this question mentioned the need for flexible working hours. Qualitative analysis for question three yielded additional emerging themes. About 22% of the study’s participants felt that their department should provide additional psychological and emotional services for frontline workers. They also believed that agencies should pay special attention to the amount of labor available and allow workers to have adequate rest. Some of the responses requested that supervisors provide inspiration and motivation and that attention be given to employee morale.

Conclusion

Key Findings

Based on our empirical findings in the preliminary analysis, a relational pattern of USVI frontline government worker burnout and ProQol were found between two distinct disasters. The mental health of frontline government workers is very important during any disaster. Wright et al. (202133) wrote that the “mental health of frontline workers is critical to a community's ability to manage crises and disasters” (p. 673). Psychological problems such as burnout or compassion fatigue can cause problems in the daily performance of employees. Frontline government workers need regular mental health assessments to provide explicit information about their psychological well-being so that they can receive proper psychological and emotional support. This information could also help workers develop and nurture psychological resiliency, manage their mental well-being, and maintain a sense of responsibility in challenging situations. These assessments should also include measuring the capacity of individuals to cope, learn, and grow from difficult experiences.

Our preliminary findings show that activities focused on increasing personal accomplishments and compassion satisfaction will reduce burnout and compassion fatigue among frontline government workers in the USVI. These initiatives could also contribute to the psychological resiliency of frontline workers and their organizations. Our preliminary findings also revealed that government organizations in the USVI could benefit from regular burnout and ProQol assessments following disasters. Hurricanes are seasonal threats to the USVI, systematic burnout and ProQol assessments can offer government administrators information to proactively address difficulties—such as emotional exhaustion, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue—that can affect the professional quality of life of their employees. Our findings also suggested that USVI government departments and agencies should focus on indirect trauma in their frontline government employees during disaster. These organizations should develop approaches to support employee growth in a way that increases compassion satisfaction and feeling of personal accomplishments during a disaster. Considerations of frontline government worker compassion satisfaction and personal accomplishments has the potential to help organizations build cultures of resiliency. Further studies on the relationship between compassion satisfaction and personal accomplishment as it relates to USVI frontline government workers experiencing indirect trauma during disasters may be a fertile area of future hazard research.

Implications for Public Health

Frontline workers expect that their organizational policies will protect them from unsafe working conditions. In concert with government policies and guidelines, organizations need to ensure that proper procedures were followed to protect employees and the public. Employees who interact with the public must be emotionally and mentally prepared. If an employee suffers from burnout or a low quality of professional life it can compromise their ability to meet the needs, safety, and well-being of the public.

Mechanisms should be put in place to ensure that employee burnout does not affect communities while they are dealing with a disaster. To minimize burnout, agencies should reduce overtime, acknowledge accomplishments, and offer additional channels of communication. Resources must be dedicated to assess and support employee well-being for the good of their organizations. This study also noted that agencies should collaborate with government organizations, such as Health and Human Services, to develop disaster mental health plans that will ensure frontline government workers get the psychological and emotional support they need.

When responding to disasters, agencies should set aside times and places where employees can receive disaster services for themselves. These services should include healthcare, mental health, shelter, food, water, clothing, and other necessities. Personnel should be allowed to create “needs” or “wish” lists for services and resources. Finally, compassion and understanding is important. Employers must ensure that employees have time for family and rest, as well as activities for boosting employee morale.

Challenges, Limitations and Future Studies

The small sample size of our study limits our ability to interpret and generalize our preliminary findings. Our findings cannot be used to represent the views of the wider populations of USVI frontline government workers. Also, the use of exploratory factor analysis in selecting and defining factor scores creates a lot of subjectivity in our decisions and interpretations. This leads to inconsistency and limits the generalizability of the analysis results. This study is a correlation analysis so it cannot identify the direction or causality between variables.

Even with these challenges, this preliminary study was able to obtain vital data to answer our research questions. The findings offered a path to understanding the relationships between burnout and professional quality of life during disasters. We are now collecting further data from the participating government organizations. We anticipate having a larger sample size with enough power to conduct a more in-depth examination that will be able to answer other important research questions.

Our findings will be provided to public managers and agency heads so they can be better able to support a positive quality of life for employees during disasters. We have noted that organizational policies related to overtime and hours of work, stress management training, and strategies for coping with emotional trauma created by disasters need to be carefully reconsidered. This study has uncovered worthwhile concepts that require further study. As established by our qualitative analysis, frontline government workers were willing to work beyond what was required of them, but often felt undervalued when they did not receive recognition and support. Future studies should focus on gratitude compensation as a way to mitigate the effects of burnout, fatigue, and exhaustion. Additional studies should explore the psychological disaster resilience of USVI frontline government workers and government organizations.

References

-

Löw, P. (2013). Natural Catastrophes in 2012 Dominated by U.S. Weather Extremes. World Watch Institute Vital Signs, 29. https://nanaimonorthrotary.org/Stories/global-natural-catastrophes-in-2012-were-dominated-by-u.s.-weather-extremes ↩

-

Trenberth, K. (2005). Uncertainty in hurricanes and global warming. Science. 308, (5729), 1753-1754. [https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1112551](https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1112551) ↩

-

Bertz, G. (1991). Natural disasters and insurance and reinsurance. U. S. Geographical Survey, 22(3), pgs. 99-102. ↩

-

U. S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet (2001). Earthquake and tsunami in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/fs141-00/fs141-00.pdf ↩

-

USVI Hurricane Recovery and Resilience Taskforce (2017). Hurricanes Irma and Maria. [https://first.bloomberglp.com/documents/USVI/257521_USVI_HRTR_Hurricanes_Irma+and+M aria.pdf](https://first.bloomberglp.com/documents/USVI/257521_USVI_HRTR_Hurricanes_Irma+and+M aria.pdf) ↩

-

World Health Organization (2013). A training tool kit for community health workers on community-based disaster risk management trainer’s guide. [https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/libcat/WHO_CBDRM_Trainers_Guide_Book_EN.pdf?ua =1](https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/libcat/WHO_CBDRM_Trainers_Guide_Book_EN.pdf?ua =1) ↩

-

Hoffman, S. (2009). Preparing for Disaster: Protecting the Most Vulnerable in Emergencies, University of California, Davis. https://lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/42/5/articles/42-5_Hoffman.pdf ↩

-

Hope, K. (2010). Willingness of Frontline Health Care Workers to Work During a Public Health Emergency. The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 25(3), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.308600251592329 ↩

-

Xiao, Y., Huang, Q., & Wu, K. (2015). Understanding social media data for disaster management. Natural hazards, 79(3), 1663-1679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-015-1918-0 ↩

-

Jaiswal, A., & Geocey, S. (2017). Efficient planning and Management in Disaster-Prone Areas. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Engineering Research, 5(7) 8-12. ↩

-

Wu, A.W., Connors, C. Everly, G.S.J. (2020). Peer Support and Crisis Communication Strategies to Promote Institutional Resilience. Ann Intern Med. 172 (12), 822-823. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1236 ↩

-

Nygaard, E., & Heir, T. (2012). World assumptions, posttraumatic stress and quality of life after a natural disaster: A longitudinal study. Health and quality of life outcomes, 10(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-76 ↩

-

Yuma, P., Powell, T., Scott, J. & Vinton, M. (2019). Resilience and coping for the healthcare Community: A post-disaster group work intervention for healthcare and social service providers. Journal of Family Strengths, 19(8), 1-17. https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol19/iss1/8 ↩

-

Raj, E. A., & Sekar, K. (2014). Stress among community level workers working in disasters. Dysphrenia. 5(1), 26-31 ↩

-

Matsuo, T., Kobayashi, D., Taki, F., Sakamoto, F., Uehara, Y., Mori, N., & Fukui, T. (2020). Prevalence of Health Care Worker Burnout During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Japan. JAMA Netw Open, 3(8), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17271 ↩

-

Burnett, H. J., & Wahl, K. (2015). The compassion fatigue and resilience connection: A survey of resilience, compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among trauma responders. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience, 17(1), 318-326. ↩

-

Tarshis, S., & Baird, S. L. (2019). Addressing the indirect trauma of social work students in intimate partner violence (IPV) field placements: A framework for supervision. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47(1), 90-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0678-1 ↩

-

World Health Organization (2019). International classification of diseases. https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/burn-out/en/ ↩

-

Fujitani, K., Carroll, M., Yanagisawa, R., & Katz, C. (2016). Burnout and psychiatric distress in local caregivers two years after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima nuclear radiation disaster. Community mental health journal, 52(1), 39-45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9924-y ↩

-

Hall, G. B., Dollard, M. F., Tuckey, M. R., Winefield, A. H., & Thompson, B. M. (2010). Job demands, work‐family conflict, and emotional exhaustion in police officers: A longitudinal test of competing theories. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 237-250. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X401723 ↩

-

Piotrkowski, C.S., & Telesco, G.A. (2011). Officers in crisis: New York City police officers who assisted the families of victims of the World Trade Center terrorist attack. Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations, 11(1), 40-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332586 ↩

-

Manzano Garcia, G.& Ayala Calvo, J. (2011). Emotional Exhaustion of nursing staff: influence of emotional annoyance and resilience. International Nursing Review, 59(1), 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00927 ↩

-

Chen, R., Sun, C., Chen, J. J., Jen, H. J., Kang, X. L., Kao, C. C., & Chou, K. R. (2021). A large‐scale survey on trauma, burnout, and posttraumatic growth among nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. International journal of mental health nursing, 30(1), 102-116. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12796 ↩

-

Prati, G., Palestini, L., & Pietrantoni, L. (2009). Coping strategies and professional quality of life among emergency workers. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 2009(1), 1–11. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-16810-004 ↩

-

Sacco, T. L., Ciurzynski, S. M., Harvey, M. E., & Ingersoll, G. L. (2015). Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among critical care nurses. Critical care nurse, 35(4), 32-42. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2015392 ↩

-

Kim, K., & Lee, J. (2019). Factors Influencing Nurses' Job Satisfaction in Integrated Nursing and Care Services Unit: Focused on Compassion Fatigue, Compassion Satisfaction and Communication Efficacy. The Korean Journal of Rehabilitation Nursing, 22(2), 124-133. https://doi.org/10.7587/kjrehn.2019.124 ↩

-

Conrad, D., & Kellar-Guenther, Y. (2006). Compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among Colorado child protection workers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(10), 1071-1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.009 ↩

-

Yadollahi, M., Razmjooei, A., Jamali, K., Niakan, M. H., & Ghahramani, Z. (2016). The relationship between professional quality of life (ProQol) and general health in Rajaee Trauma Hospital staff of Shiraz, Iran. Shiraz E-Medical Journal, 17(9), e39253. https://doi.org/10.17795/semj39253 ↩

-

Stamm, B., 2010. The Concise ProQOL Manual, second ed. The ProQOL.org, Pocatello. ↩

-

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory–General Survey. In C. Maslach, S. E. Jackson, & M. P. Leiter (Eds.). The Maslach Burnout Inventory: Test manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. ↩

-

Hinkle, D. E., Wiersma, W., & Jurs, S. G. (2003). Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences (663). Houghton Mifflin College Division. ↩

-

Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research (2020). Review of the USVI Territorial Economy 2019. Available at http://usviber.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Review-of-the-VirginIslands-Economy-3-25-20.pdf ↩

-

Wright, H. M., Griffin, B. J., Shoji, K., Love, T. M., Langenecker, S. A., Benight, C. C., & Smith, A. J. (2021). Pandemic-related mental health risk among front line personnel. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 137, 673-680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.10.045 ↩

Francis, K., Clavier, N., & Hendrickson, K. (2021). Frontline Government Workers: Assessing Post-Disaster Burnout and Quality of Life (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 8). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/frontline-government-workers-assessing-post-disaster-burnout-and-quality-of-life