Participatory Budgeting

A Community-Led Intervention for Resource Security Following a Disaster

Publication Date: 2024

Translating Research Into Action

To support others in developing participatory budgeting initiatives, we are sharing a packet of materials that we used to develop our project, including a project plan template, outreach materials, proposal submission form and template, and voting form template. Click on the image below to see these resources.

Introduction

Hazards and disasters put communities at risk with disruptions to food, energy, and water (FEW) systems. Addressing these insecurities requires an integrated understanding of how FEW systems interact, including the physical and social resources available within the community, through approaches that can fully capture localized contexts. We aimed to understand these experiences, in the community of Corcovada—a rural neighborhood with a disproportionately older population in western Puerto Rico.

Our team has been developing this project in phases over three years with previous Public Health Disaster Research Awards. In Project Phase 1, Social Capital, Community Health Resilience, and Compounding Hazards in Corcovada, Puerto Rico, we collaborated with 16 community leaders to understand these interactions. We found that community leaders worked together closely in response to hazards and disasters between 2010-2021, bringing to the community physical resources while also building the relationship-based social capital that is key to resilience. While events like Hurricane Maria (2017) allowed the community to cooperate closely, COVID-19 was different as it constrained the ability of leaders and residents to interact. This is a major challenge because social relationships allow communities to fill unmet needs and respond when critical infrastructure fails or government agencies siphon resources. In Project Phase 2, Assessing Intra-Community Public Health Impacts from Compounding Food, Energy, and Water Insecurities, we developed a household survey for public health and community leaders to assess their FEW systems and community health throughout the disaster cycle. This allows them to identify specific household resource needs and health concerns.

In the first two project phases, residents expressed that they wanted solutions that would stay in the community to aid emergency preparedness and to encourage community connections. The objective of Project Phase 3 was to bring solutions to the community that support community cohesion through active participation and engagement. We proposed participatory budgeting—a democratic model for budget decision-making—for residents of Corcovada to decide on solutions to challenges of food, energy, water, and/or public health. Participatory budgeting starts with the creation of a steering committee, which oversees creating the "rules" for the entire process (Godwin, 20181). Then citizens provide proposals for the budget (Cabannes, 20212; Martínez, 20233) and the steering committee evaluates whether the different proposals fit the proposal requirements (Cabanes, 2021). Residents then vote on the project proposals, which are then implemented.

Participatory Budgeting Teams

As Table 1 shows, our project consists of three main groups with different roles throughout the project: the core research team, the steering committee, and the community members. The core research team is made up of community-based researchers and external researchers. Our primary community-based researchers—who are also community leaders in Corcovada—are Enid Quintana, Edna Torres, and Fernando Cuevas. Edna Torres is the president of the Corcovada Community Aqueduct System—a self-managed aqueduct that provides potable water to 140 households in Corcovada. The core research team also includes the Project Coordinator, Javier Torres, who has helped to conduct the community outreach events, form the steering committee, and oversee the project in Corcovada. These community-based researchers and the Project Coordinator continue to be on-the-ground helping to oversee the participatory budget process.

Table 1. Project Roles and Responsibilities

| Role | Person or People in Role | Responsibilities |

| Core Research Team | Made up of community-based and external researchers. This also includes the Project Coordinator. | ● Secure funding for project ● Facilitate dialogue ● Select the steering committee ● Support evaluating if proposals meet eligibility criteria ● Support the implementation of winning proposals |

| Project Coordinator | Community member from Corcovada who is also a community-based researcher and member of Core Research Team. | ● Lead formation of the steering committee ● Lead outreach for proposal collection ● Coordinate regular meetings of steering committee ● Lead logistics for winning proposal implementation |

| Steering Committee | Made up of seven community members identified by the community-based researchers and the Project Coordinator. | ● Make decision on all major project activities ● Support the call for proposals and outreach to community ● Evaluate if proposals meet eligibility criteria ● Support the implementation of winning proposals |

| Community Members | Anyone who is a resident of Corcovada, Puerto Rico. | ● Develop and submit proposals ● Vote for preferred proposals |

For the implementation of this project and to support community engagement, the community-based researchers and Project Coordinator identified seven community members (three female and four male) to participate in the steering committee. The community-based researchers, Project Coordinator, and the steering committee worked together on community outreach; their activities included making home visits, sharing calls for proposals through social media and WhatsApp groups, and making announcements in the local church.

The steering committee and core research team communicated with each other consistently throughout the project using designated WhatsApp chats. The role of the core research team throughout the project focused on facilitating dialogue for decision-making regarding the different steps of the participatory budgeting process. We also met together in three virtual meetings to make decisions about the design of the participatory budget project and the call for proposals. The core research team and the steering committee also worked together to facilitate the voting exercise and we currently are implementing the winning proposals.

Project Objectives and Activities

The main objective was to engage the community in a participatory budgeting exercise that contributed to building community cohesion and the physical resources and social capital needed to address needs regarding FEW securities and public health. To do so, our project required several activities outlined in Table 2, including developing a steering committee, creating a call for proposals, a voting exercise, and sharing responsibilities for the implementation of the winning proposals. At the outset of the project, the core research team and steering committee developed a plan and guidelines for solicitation of proposals. Outreach plans included infographics and videos; these materials provided information about the participatory budget process and requirements for proposal submission. Steering committee members shared these materials on social media, in WhatsApp groups, and at home visits or places of community gathering, such as the church and community aqueduct billing office.

Table 2. Project Activities and Objectives

| Project Activities | Objectives |

| Formation of Steering Committee | To involve residents directly in the management of the project. |

| Meetings | To delegate roles and responsibilities across members of both the research and steering committee. For residents of Corcovada to actively guide the objectives of the project |

| Call for Proposals | To encourage residents of Corcovada to develop ideas that can support their community to respond to challenges related to food, energy, water and/or public health and disaster emergency management |

| Outreach | To encourage residents to share their ideas on possible projects, submit proposals with those ideas, and vote for their preferred proposals. To support community cohesion through public participation. |

| Voting on Proposals | To give residents of Corcovada an opportunity to make decisions about the projects implemented in their community. |

| Implementation of Proposals | To implement the winning proposals and support disaster emergency management with a focus on food, energy, water, and/or public health. |

Proposals for this exercise needed to address issues of food, energy, water insecurity and/or public health and not exceed $8,000. Community members had the option to submit proposals online or on paper. Any community member could submit one proposal to the Project Coordinator or to a member of the steering committee. The proposal form explained participatory budgeting and then asked the applicant to explain:

- What is your idea for a water, food, energy, and/or health project?

- How would you implement this project? (optional)

Community members submitted a total of 46 proposals. The steering committee and two core researchers (Roque and Painter) evaluated each submission to determine if it met the eligibility criteria and found that 17 were not eligible because their expected costs were over $8,000. Of the 29 remaining proposals, several were so similar to each other that the reviewers merged them together. That merging process resulted in the selection of nine proposals to be presented to the public for the vote.

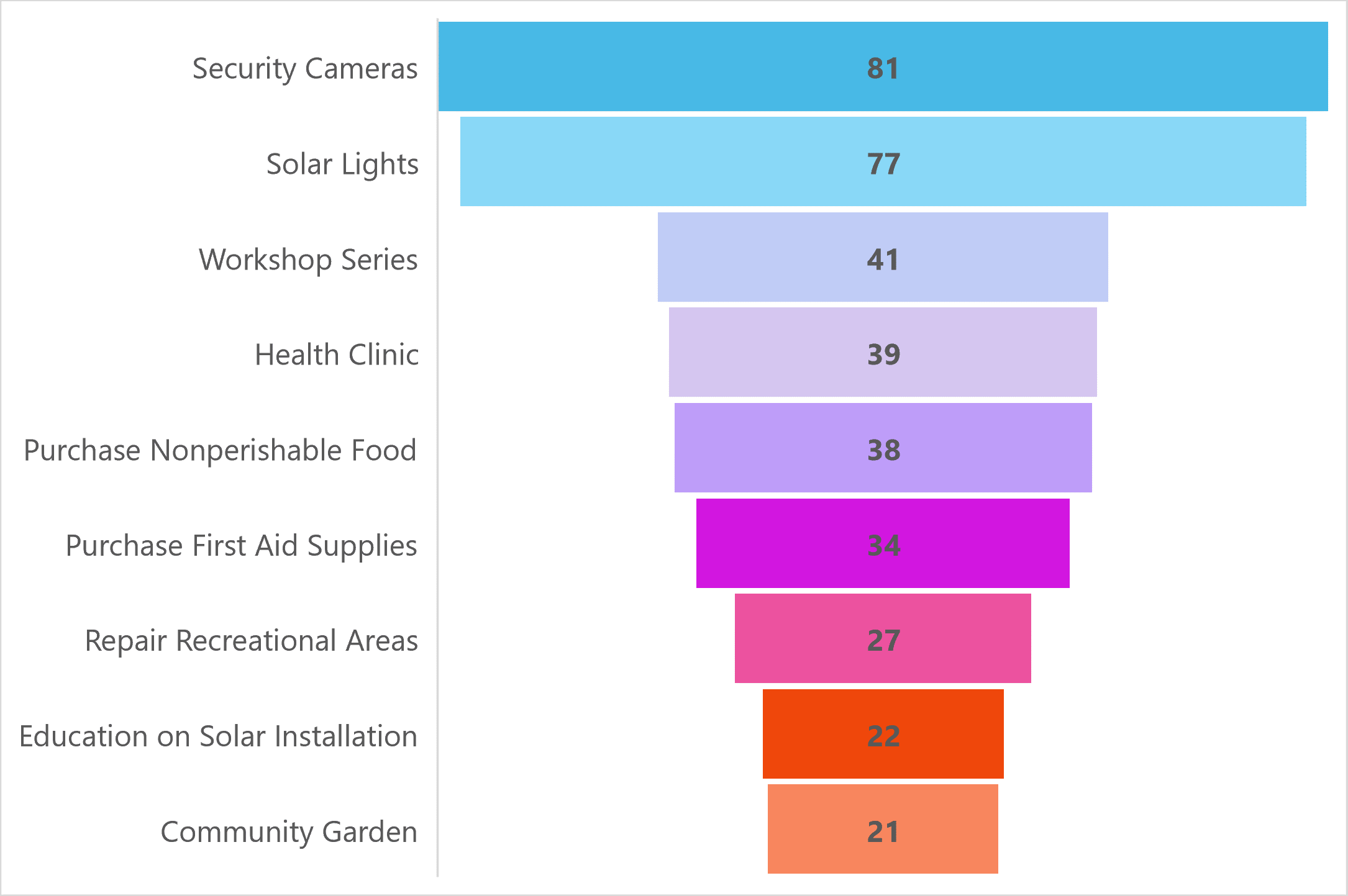

Community members then voted via online form or in-person at the Corcovada Community Center. Community members were asked to vote by ranking proposals in order of their preference so, if funds permitted it, multiple proposals could be implemented. Of the 610 community members, 135 or 22% participated in voting. Residents were asked to vote for their top 3 proposals by ranking them 1 to 3 where 1 represented highest priority and 3 represented the least priority. The three proposals that received the most votes were solar powered streetlights, public cameras, and workshop series. Full results are presented in Figure 1. Currently, the core research team and the steering committee are working to implement the three winning proposals.

Figure 1. Voting Results

Three proposals were selected by the community for implementation, each aimed at enhancing disaster resilience and addressing emergency public health concerns. Solar-powered security cameras will be installed in strategic locations to protect current community assets that bolster community resilience (e.g., solar panels for the water aqueduct and the community center) and in areas where security incidents have previously occurred. These cameras aim to reduce residents' distress during normal times and provide a swift response during emergencies by monitoring shared assets and activities in these parts of the community. The community's volunteer-based security team will monitor the cameras. Solar streetlights will be installed in five community areas: two community centers, a multi-purpose center (re-purposed school), and the community recreational area. These locations serve as gathering points for residents during emergencies or disasters to discuss action plans, address public health concerns, receive and distribute donations, and conduct related activities. Additionally, solar streetlights will be installed in a part of the community currently lacking lighting, where accidents have occurred due to the absence of light. A series of educational workshops will focus on topics such as food security, water security, energy security, public health, and emergency preparedness. These workshops aim to continue discussions on preparedness and resilience strategies while supporting ongoing community cohesion. A workshop coordinator, who is also a resident of the community, has been employed to oversee this task. The workshops will be hosted in the community center.

Each of these projects supports disaster resilience and emergency public health concerns by enhancing the community's infrastructure, safety, and knowledge, thereby aiming to strengthen the overall resilience and preparedness of the Corcovada community.

Results

Our main project objective was to conduct a participatory budgeting exercise to build community cohesion and capacity to mitigate disaster harms. Throughout the exercise, we found two important results that support our project objectives. First, we found that our project ignited active community participation from Corcovada community members at every stage of the process. We learned from Phase 1 of our project that public participation and interactions eroded when the pandemic began. This project brought an opportunity to have more conversations (throughout outreach, voting events, and sharing results) about emergency management and resource security. The winning projects—solar streetlights for power outages, community workshops on food, energy, water, and public health, and a public camera system to protect community assets—represent not only technical, but also social solutions. We expect that as these projects are implemented, community members will have more opportunities to be educated on these topics, interact with each other, and rebuild social connections. Considering the history of the community with hazards and disasters, we expect this will ultimately support community resilience to future events.

Second, the participatory budget exercise supports community-led intervention in resilience to hazards and disasters. Having an opportunity for community members to propose ideas for a community budget was the first project of its type for Corcovada. Community leaders shared the value of feeling that the proposed ideas and implementation were their own because of the opportunity to engage in decision-making throughout all stages of the project. Having community-based researchers, who are also community leaders, as co-investigators on the project and engaging with community members increased the value of the research efforts. Engaging in three different research exercises over the course of several years (2021-present), community leaders and members were able to identify priorities and make the project their own, supporting the long-term maintenance of this collaboration.

The participatory budgeting exercise specifically represents a full circle of exploration (Phase 1), product creation (Phase 1 and 2), and implementation in the community of tangible outcomes (Phase 3). Leaders have acquired knowledge and relationships within and across communities of power (e.g., universities, non-profit organizations, government agencies) that they can use to continue developing new projects and advance the goals of community betterment. We aim for this project to be a spark to other community-centered projects that leaders can seek out and apply for in the future.

Reflections and Lessons Learned

Our project revealed many benefits to participatory budget projects, as well as challenges that can help future teams implement this type of program. We found that having deep connections to the community is essential to ensure participation and engagement from residents. Our team included community leaders and researchers from the community. This project took place three years into a multi-stage community-based participatory project. Below we outline this lesson learned and others.

- Ensure research team members and project leaders are deeply connected to the community.

- Avoid imposing the biases of non-community members over community preferences and perspectives.

- Be efficient with the use of the community’s time. Community leaders and residents are managing different responsibilities and its important to consider the time commitment as well as the roles and responsibilities of each member involved.

- Maximize the reach and intelligibility of each aspect of the project by using various means to explain it to community members (e.g., infographics, videos, social media, instant messages, church visits, direct outreach, and paper and online voting).

- Leverage monetary investment to enable community participation in project development; participation should include the generation of project ideas among community members (some of which can be developed in future projects) and community-led analyses about local needs and desires. These analyses should also give community members the opportunity to identify weaknesses in infrastructure that merit addressing, assess the strengths and shortcomings of project ideas, and evaluate which ideas might work and which need further development.

- Involve the community in every aspect of the project and maintain frequent communication and updates. This elicits rapid and constant feedback that informs the project’s successful implementation and increases the breadth of our collaboration.

- Empower community members to lead decision-making processes for the project so that it aligns with their desires and capabilities.

- Ensure community leaders have resources and skills to maintain the project.

Participatory Budgeting Planning Guide and Outreach Materials

Participatory Budgeting programs are democratic processes where citizens are directly involved in a shared budget. To support others in developing participatory budgeting projects, we have developed this Participatory Budgeting Guide. The packet includes a project plan template, sample outreach materials, a sample proposal submission form and template, and a voting form template. Some materials are provided in Spanish with an English translation in plain text.

We hope others interested in doing participatory budgeting in communities where they live or work can use this packet to develop their own projects. We will be providing updated project outputs and materials, including information about how we implemented the winning proposals on our project website. We developed this website to document our collaboration with the Corcovada community. Materials and outputs from Phases 1 and 2 are also available there.

Acknowledgments. We would like to express our profound gratitude to the Corcovada community for welcoming our research team and for their active and invaluable participation in this collaborative effort. Their willingness to invest time and effort has been a cornerstone of our partnership, for which we are immensely thankful. Special thanks are extended to our Co-PIs—Edna Torres, Enid Quintana, and Fernando Cuevas—for their visionary leadership and dedication. Their contributions have been pivotal to the project's success. We are equally grateful to the members of our participatory budgeting steering committee, as well as to all the residents who eagerly proposed ideas and participated in the voting process, demonstrating a commendable commitment to their community's development. Further, we cannot overlook the extraordinary role of Javier Nieves Torres, our project coordinator. Javier's efforts have been vital in ensuring that our project not only stayed on track but also thrived. This project stands as a testament to the power of ethical and meaningful partnerships, showcasing how they can propel both scientific advancement and fulfill community needs. We are deeply appreciative of everyone's engagement and contributions, which have been invaluable to the project's impact and success.

References

-

Godwin, M. L. (2018). Studying Participatory Budgeting: Democratic Innovation or Budgeting Tool? State and Local Government Review, 50(2), 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X18784333 ↩

-

Cabannes, Y. (2021). Contributions of participatory budgeting to climate change adaptation and mitigation: Current local practices across the world and lessons from the field. Environment and Urbanization, 33(2), 356–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/09562478211021710 ↩

-

Martínez, A. D. (2023). Power and Positionality in Participatory Budgeting. American Behavioral Scientist, 67(4), 505-519. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642221086954 ↩

Roque, A. D., Quintana, E., Torres, E., Tormos-Aponte, F., Painter, M. P., & Cuevas, F. (2024). Participatory Budgeting: A Community-Led Intervention for Community Resilience to Disasters. (Natural Hazards Center Community Engagement Brief Series, Brief 5). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/participatory-budgeting