Photovoice and Cultural Competence in Disaster Recovery in St. Croix

Publication Year: 2021

Executive Summary

Overview

Cultural competence is crucial for effective service delivery, including disaster recovery work. Yet, the literature on cultural competence sheds little light on such work. The increasing number of disasters in the Caribbean region, and therefore the increasing vulnerability of the affected communities, call for intensifying the focus on the effectiveness of post-disaster workers. Disaster workers who lack cultural competence can be less effective in their mitigation efforts, especially in developing areas such as the U.S. Virgin Island of St. Croix. There is, however, a lack of studies on the cultural competence among disaster workers in this region. Results from studies could be instructive in raising awareness of the importance of culturally grounded disaster work and establishing the need for training sessions for disaster workers. This study, which was conducted in St. Croix, fills the gap by employing a photovoice methodology to explore the disaster workers’ cultural competence through both their own personal lens and that of community members.

Research Design

The study employed a photovoice methodology, which is a community-based participatory approach that uses photographs to examine social concepts and problems and empowers participants by engaging them in collecting and analyzing data (photos). The methodology seeks to achieve social justice in its process and outcomes as it actively engages community members in the research. Thirty individuals (20 community residents and 10 disaster workers) participated in the study. Most participants were female (N=21; 72%); under the age of 56 (N=19; 63%); and Black (N= 25; 83%).

Research Questions

Two specific questions guided this inquiry: (1) What are people’s perceptions of the impact of cultural competence on disaster recovery efforts? and (2) are there similarities or differences between the worker perceptions of their own cultural competence and community member perceptions of the workers’ cultural competence?

Implications and Conclusion

Analysis of the photos and focus group discussion revealed six main themes about the participants’ perceptions of cultural competence in post-disaster recovery. Negative themes included neglect, cultural blindness, lack of awareness of structural barriers, bias treatment, and contribution to social problems. Fewer positive views were expressed, although themes such as leveraging community support and addressing language barriers were noted. Disaster workers were more likely than the community residents to express these positive views.

Participants shared recommendations for improving cultural competence in post-disaster recovery. These included:

- Monitor the progress and method in which post-disaster work is done.

- Give community members the opportunity to provide feedback on post-disaster work.

- Identify cultural ambassadors in different fields to work alongside and help non-Crucian workers (such as non-islanders from the United States) as they do post-disaster work.

- Pay greater attention to vulnerable populations, such as people with disabilities.

- Establish a robust network of community members in the community so that information about a disaster can be easily conveyed.

The research findings hold important implications for disaster work in the region and for public health in general. As disasters continue to impact every corner of the globe, disaster workers will be called on to travel to different communities and countries with which they are unfamiliar. Further, they will be interacting with disaster survivors who have very different backgrounds from them. This reality points to cultural competence training as an integral part of the preparation to do disaster-related work with diverse local communities around the globe. Disaster work that is devoid of cultural competence could hinder the public health focus of preventing disease, promoting health, and prolonging life among all people.

Introduction and Literature Review

Cultural competence is crucial for effective service delivery, including disaster recovery work (Mack et al., 20071). Yet, the literature on cultural competence sheds little light on post-disaster work. The increasing number of disasters in the Caribbean region and therefore the increasing vulnerability of the affected communities call for intensifying the focus on the effectiveness of post-disaster workers. We suggest that disaster workers who lack cultural competence can be less effective in their mitigation efforts, especially in developing countries such as the U.S. Virgin Island of St. Croix.

St. Croix is home to approximately 50,000 individuals and is one of the largest U.S. Virgin Isles (St. Croix Facts and History, 20212). St. Croix became a territory of the United States in 1917 after an exchange with the Danish for military acquisition. Today, the main industries of the island are tourism, agriculture, and oil refinery. The two main towns on the island are Christiansted and Frederiksted (St. Croix Facts and History, 2021). The last of the native people to inhabit St. Croix were the Carib. Originally from South America, they were not the first natives on the island but were the ones who greeted Christopher Columbus in 1493 (St. Croix History and General Information, 20203). The Carib coexisted with the Spanish newcomers for almost a decade before new Spaniards arrived and raided the island for slaves. The Caribs abandoned the island after a military uprising. The current natives of St. Croix call themselves “Crucian.” Because of the influx of immigrants both in the past and present, it is difficult to identify who are truly native Crucian and whose families immigrated to the island (St. Croix History and General Information, 2020). The official language of the island has been English since 1917, when the island was purchased by the United States.

Hurricanes Irma and Maria hit the Virgin Island of St. Croix in September 2017. These two devastating Category 5 storms left the island of St. Croix in disarray. It is reported that 70% of the island’s homes and structures suffered damage from the storm during Hurricane Irma. Hurricane Maria’s destruction on the island led to widespread flooding and mudslides from the estimated 5–7 inches of rainfall. With wind speeds reaching up to 187 miles per hour, damage to the island was inevitable. Seventy-five days after Hurricane Maria made landfall, 60% of residents were still left without electricity (Santiago, 20174). The island of St. Croix is vulnerable to these devastating storms every hurricane season, which can have a daunting impact on the main economic driver of the island—tourism. For example, when detrimental storms rip the island apart, travel is restricted for outside guests and tourism halts. This leaves many without work and therefore without an income to support themselves and their families.

Cultural competence is defined as “knowledge of others; knowledge of self; skills to interpret and relate; skills to discover and/or to interact; valuing others’ values, beliefs, and behaviors; and relativizing oneself. Linguistic competence plays a key role in overall cultural competence” (Deardorff, 2006, p. 247). The dimensions of cultural competence have been commonly described as awareness, knowledge, and skills. Individuals and organizations express varying levels of these traits along a continuum such that cultural competence is a development process (Cross et al., 19895). This continuum contains six states:

- cultural destructiveness, which refers to people’s attitudes or organizational decisions that seek to destroy cultural groups;

- cultural incapacity, which refers to an individual’s or organization’s lack of skills or practice to accommodate the unique needs of groups;

- cultural blindness, which overlooks the role of race in shaping the outcomes of individuals, including service approaches and strategies that overlook differences across and within communities;

- cultural pre-competence, which reflects an increase in knowledge and awareness of differences with increased effort to provide culturally grounded services, but there is still room for growth;

- cultural competency, which is articulated in the mission and reflected in policies and practices that engage the community in service delivery in a way that values their voices and experiences; and

- cultural proficiency, which is demonstrated by individuals and organizations holding diversity in high esteem and consistently using it to guide every aspect of their work and behavior.

The last two stages, cultural competency and cultural proficiency, reflect individuals and organizations that value diversity as well as accept and respect differences.

There is a dearth of research on culturally competent service delivery in the Caribbean and more specifically service delivery relevant to natural disasters (Remington, 20176; Warfa et al.,20147). Following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Remington (2017) explored cultural competence among post-disaster response and recovery workers. The study found that despite the perceived importance of cultural competence among the workers, less than half had received training in this area. Further, the study found that organizational policies hindered the development of cultural competence. Warfa and colleagues (2014) conducted a critical review of the literature on post-disaster work, specifically mental health, in Haiti, Mexico and the United States. They found little research and evidence of culturally grounded post-disaster work.

Although these studies added to the knowledge base on cultural competence in disaster recovery in the Caribbean literature, gaps exist. For example, the research on cultural competence and disaster recovery and response is largely done from an empirical and expert-driven standpoint (Dickinson, 20128). This positivist approach to research prioritizes the voices of experts, while excluding the perspectives of nonexperts who are often marginalized in society and bear the brunt of society’s social and natural problems, such as disasters. In this vein, little is known about community members’ perceptions of cultural competence among aid workers and its impact on disaster recovery efforts.

We seek to fill this gap by employing a community-based research methodology called photovoice, which aims to achieve social justice both in its process and outcomes by deliberately engaging community members in the research process (Israel et al., 19989). Photovoice was developed by Wang and Burris (199710) to use photographs collected by research participants, who go on to provide an interpretation of their photos through narratives to help explore themes about social concepts or problems. It represents a paradigm shift in that the power is shifted from the researchers to the participants; moreover, photovoice is transformative in that it changes participants’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviors (Strack et al., 201011). Although photovoice is a useful tool in advancing social justice and giving voice to those most impacted, its application to cultural competence and disaster research is lacking. We seek to contribute to the literature in this area while elevating the significance of culturally grounded work among disaster workers.

There is a growing body of participatory action disaster studies using photovoice (such as Annang et al., 201612; Bishop et al., 201313; Schumann et al., 201914; Yoshihama & Yunomae, 201815). Participatory action studies involve researchers and participants working together to explore a social problem (Baum et al., 200616). For example, Annang et al. (2016) used photovoice to capture the long-term impact of a disaster on the quality of life of South Carolinians. Similarly, Yoshihama and Yunomae (2018) used it to explore the impact of the Great Tohoku Earthquake of 2011 on women. Schumann et al. (2019) highlighted the benefits of using photovoice in hazard and disaster science and reviewed studies that have employed this methodology. These studies provide a basis for employing photovoice in this current study in St. Croix.

Methods

Research Questions

This study explored the concept of cultural competence in post-disaster work in St. Croix. Two specific questions guided this inquiry:

- What are people’s perceptions of the impact of cultural competence on disaster recovery efforts?

- Are there similarities or differences between the workers’ perceptions of their own cultural competence and the community members’ perceptions of the workers’ cultural competence?

Data and Methods

This study aimed to explore individual and structural cultural competence in disaster recovery efforts in St. Croix using a photovoice methodology, which is qualitative in nature. Qualitative studies dig deep into the experiences of people during the post-disaster recovery efforts, with respect to the impact of culturally grounded work, or the lack thereof, on their lived experiences. This approach helps the researcher to understand “the social world through an examination of the interpretation of that world by its participants” (Jonkman, 200517).

Photovoice is a unique community-based research methodology, which seeks to achieve social justice both in its process and outcomes as it actively engages community members in the research process. The methodology uses photographs to help establish themes about social problems, such as cultural competence (Wang & Burris, 1997).

Sample Size and Participants

The researchers recruited 36 participants, however only 30 completed the project (the other six individuals agreed to participate but did not submit any photos). Twenty of the participants were community residents and 10 were disaster workers, representing two main disaster organizations—St. Croix Long-Term Recovery Group (LTRG) and the Red Cross. All participants were above the age of 18. Participants identified in age groups 18–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, or 56 and older. A systematic review of the photovoice methodology found that sample sizes ranged from one participant to 82 participants (Shumba & Moodley, 201818). The combined participant group of 30 individuals is well within this range, allowing the researchers to get a deep understanding of cultural competence in disaster work. The study participants were recruited using convenience and snowball sampling techniques. The researchers made initial contact with two local organizations in St. Croix (Environmental Association and the Rotary Club of Mid-Isle), which connected the researchers to individuals and community groups on the island. These organizations also posted information about the research on their social media pages. Through that initial partnership, the research team was able to connect with other organizations—such as the LTRG, the Red Cross, and the Women’s Coalition—from which study participants were drawn. The LTRG is composed of individuals from a wide cross section of the community including faith-based, nonprofit, government, business, and other organizations that assist individuals in St. Croix to recover from natural disasters. The Women’s Coalition contributes to the development of St. Croix by helping women impacted by violence. Many community residents for the study were recruited from connections with the Women’s Coalition.

Procedure

Photovoice is a community-based participatory approach that uses photographs to examine social concepts and problems and empowers participants by engaging them in the process of collecting and analyzing the data (photos). The strength of photovoice is reflected in its ability “to enable people (a) to record and reflect their community’s strengths and concerns, (b) to promote critical dialogue and knowledge about personal and community issues through large- and small-group discussion of their photographs, and (c) to reach policy makers” (Wang, 199919, p. 185).

For this study, two recruitment flyers were developed and sent to individuals and organizations to further disseminate. One flyer was tailored to recruit disaster recovery workers and the other tailored to recruit community residents. Both flyers provided a brief description of the study and the photovoice methodology and offered a $50 incentive for the participants’ time. Individuals interested in the study were asked to contact the research team via the email address provided on the flyers. Recruitment for the study was on a rolling basis and occurred over a two-month period.

Individuals (community residents and disaster recovery workers) who expressed interest in participating in the study were sent an email by the research team, which further described the project and the photovoice methodology and included an informed consent letter. The email also explained what is meant by cultural competence. The concept was explained to the participants as disaster recovery workers having respect for other cultures and demonstrating the knowledge, skills, and behavior needed to work effectively across cultures. Consistent with the nature of the photovoice methodology, participants were told about the technical and ethical considerations of the project. Specifically, they were asked to respect people and property while taking photos. For example, participants were told not to invade people’s privacy and to be judicious in the photos that they captured, ensuring that they were not taken in a way that would harm the individuals (Wang & Burris, 1997). The participants were asked to take photos (at least three to help boost the data collection) to represent their perceptions of the extent of culturally competent disaster recovery work in their communities. Participants were informed that the project was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Winthrop University.

Participants were asked to accompany each photo with a narrative detailing (a) the photo’s content, (b) where was it taken, and (c) its reflection of cultural competency in disaster work (with an explanation of why it does or does not reflect culturally competent work). The researchers followed up by phone with individuals who needed more clarity on the instructions. Individuals indicated their consent to participate by taking and emailing their photos.

Once the participants received the email instructions, they took an average of three weeks to email their photos and narratives. Participants submitted an average of three photos. Consistent with the photovoice methodology, after the photos were submitted, a focus group was held with 15 available participants. The participants were sent the consent letter ahead of the meeting and the letter was read at the beginning of the focus group. Participation in the focus group indicated their consent. The focus group lasted 75 minutes via Zoom and was recorded. The recorded file was transcribed for analysis.

During the focus group session, participants shared their photos and elaborated on the perceived cultural competence dimensions of each photo and its impact on their lived experiences. The focus group had a mix of community individuals and disaster workers to facilitate deeper learning of the issue. The focus group questions were guided by the following themes modified from Sethi (2016)20:

- theme (description of the image),

- cultural competence status (the specific issues that the photo represents), and

- message (the messages to be conveyed to disaster workers and government officials).

Data analysis

The photovoice study followed Wang and Burris’ (1997) three-step process of analyzing data—selecting, contextualizing, and coding the data—with the aim of building critical consciousness of cultural competence in disaster work among participants and the data users (Freire, 197021). The first step, selecting the data, is essentially the data collection process, in which the participants decided what photos to submit to the research team. Each photo was accompanied with a narrative that included information on the context of the photo. As the researchers received the photos and narratives from each participant, they began to sort them into different categories based on context. However, the coding of the data truly began during the focus group discussion. During the focus group session, the participants shared their thoughts about their photos and were asked to reflect on common themes that emerged from the participants. Specifically, they were asked to group the photos and narratives into themes about their perceptions of the cultural competence of post-disaster workers in St. Croix. The participants shared their views on the themes that emerged.

Following the group discussion, the research continued with a thematic analysis of the narrative that accompanied each photo. The narratives were carefully reviewed and sorted to account for the themes identified in the discussion and any other emerging themes. This was done until saturation was reached. Text that supported the themes were extracted.

Positionality, Reciprocity, and Other Ethical Considerations

Researcher positionality can impact any research project, including the current study (Kerstetter, 201222; Muhammad et al., 201523). For example, Muhammad et al. (2015) stated that “the question of who is on the research team may facilitate or hinder (or act in contradictory ways upon) the capacity to engage with CBPR [Community Based Participatory Research] community partners, may affect knowledge construction and research use, and may ultimately impact the goals of the research itself” (p.2). Members of the research team are Northern American, which could have conveyed an authoritarian cultural imperialism and expert-driven position to Caribbean participants. However, looking inward to understand our own positionality based on location and academic status was a first step in creating effective communication and engagement strategies. For example, although the researchers reside in North America, one member of the research was born and grew up in the Caribbean and was therefore able to use her background to connect with potential participants.

Several important lessons were gleaned from conducting this research project. First, it is important to establish relationships when conducting research in communities that the researchers are not a part of (Kerstetter, 2012). Establishing relationships with local organizations at the very beginning of the project was central to recruiting participants for the study. The relationships directed us to key informants and, more importantly, it helped to create trust between the research team and potential participants. For example, one participant said “when [influential person] calls and says it is a good idea for you to do something, you just do it.”

Second, finding common ground is necessary to gain trust among participants in communities where researchers are not known. The idea of participants having to share their perceptions through photos required more emotional involvement than simply completing a survey. Several participants admitted to ignoring recruitment emails from the research team inviting them to participate until they were informed of the Caribbean roots of one of the authors, which conveyed a sense of solidarity. In follow-up phone calls, participants shared that they were happy that the researcher mentioned their Caribbean roots, because they are often weary of North Americans, who don’t have a vested interest in the island, conducting studies. As the researcher expressed similar sentiments about studies being conducted in St. Vincent and the Grenadines (their home country), the participants, who had ignored several email invites from the research team, stated that they were more open and willing to participate in the study.

Another important lesson learned is the centrality of working with a local group when conducting studies in a different country or in a minority community. Prior to establishing relationships with the LTRG for this study, we had a difficult time recruiting disaster recovery workers on our own and securing their confidence in the integrity and intent of the research project.

Another ethical concern was that participants were preoccupied with the concerns of the COVID-19 pandemic. Several potential participants mentioned that they were busy taking care of things related to the pandemic. Although we desired a more robust participation, we were careful to respect the needs of individuals and sensitive to their current context.

Findings

Results

A total of 30 individuals participated in the photovoice. The majority of participants (N=20) were community residents, while 10 individuals were disaster workers. The community participants came from various communities across the island. The disaster workers, who were all based on the island, included locals as well as North American expats. Most participants were female (N=21; 72%); under the age of 56 (N=19; 63%); and Black (N= 25; 83%).

Six themes emerged from the photographs, narratives, and focus group discussions regarding participants’ perceptions of cultural competence in post-disaster recovery. Negative themes included neglect, cultural blindness, unawareness of structural barriers, bias treatment and contribution to social problems. Fewer positive views were expressed, through themes such as leveraging community support and addressing language barriers (see Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of Photovoice Results

| Theme | Sample Photos | Example of Narrative |

| Neglect | 1–4 | “These pictures show the government’s lack of attention towards issues and problems the people of the community face that need to be addressed and never are.”

“I chose to take pictures of those buildings because these are buildings that played a role in the community. They’re not buildings that people saw but never knew what it was.” |

| Cultural Blindness | 5–6 | “The issues with home deeds is not new. Saw it with Hurricane Hugo. Why have we not helped people?”

“FEMA’s (Federal Emergency Management Agency’s) requirements for assistance (i.e., deeds to property, receipts, insurance, etc.) was a hindrance to many people attaining assistance.” “Debris sat piled up for weeks after Hurricane Maria.” |

| Unawareness of structural barriers | 7 | “The fact that FEMA required you to register on the internet was a BIG JOKE. This isn’t the mainland; this is an island without all of the internet connections certainly not for older generations. I felt that if we can send thousands of troops into Iraq to fight a war then why wouldn’t they know how to fight the WAR following a Hurricane Category 5.” |

| Contribution to social problems | 8-9 | “A housing crisis has been created as the workers drove up the price of rent. Prices skyrocketed. Now the locals cannot afford properties leaving housing essentially unavailable for them.” |

| Bias treatment | 10-12 | “The extravagance of the Fred (a Bed and Breakfast venue right across the street from the library) and the neglect of the library speaks to the populations they serve and therefore the priorities. The Fred caters mostly to whites and clients with money. The library caters to everyday residents that use the computers because they don’t own one. Check books out on loan because they can’t afford to purchase them.” |

| Leveraging community support | 13-15 |

“We have community caring for community.”

“It was the relationship and care that the volunteers had with the homeowner—that mutuality, partnership, and genuine concern for each other.” “They asked how they could help and didn't assume they knew what was best for the community. They worked collaboratively with us to plan the party and they were really interested in giving back to the community.” |

| Addressing language barrier | 16 | “Resourcing the WHOLE of the community through offering materials in various languages spoken on the island.” |

Neglect

The neglect of repairs to buildings surfaced as the most common theme. Residents echoed through their photos and narratives that many structures, including places that are important to the community such as gas stations, libraries, playgrounds, traffic lights, and historical buildings, were not repaired. Many participants believed that the widespread presence of blue tarps on buildings symbolized disrepair.

Lack of cultural competence was presented as neglect because it showed a lack of understanding for the needs that members of the community have. The photos and captions in Figures 1-4, submitted by participants, illuminate this theme. For example, one participant shared this about Figures 1: “These pictures show the government’s lack of attention towards issues and problems the people of the community face that need to be addressed and never are.” Another wrote this about Figure 2: “These are pictures of actual ceilings taken recently. In some, I can see the light shining through the blue tarp. This is cultural incompetence, because it’s failure to move the disaster recovery process along and to cut through the usual BS that impedes the process.” Another resident noted, “I chose to take pictures of those buildings because these are buildings that played a role in the community. They’re not buildings that people saw but never knew what it was. These are buildings that played a specific role in the community.” Another participant said, “So much has been overlooked in the recovery efforts—from a storm that occurred over three years ago—for a poor community in dire need of recreational outlets.” The participants said this in reference to the playground in Figure 3 and the school shown in Figure 4, that are still damaged and in need of repair.

Figure 1. Participant Image of a Hurricane-Damaged House With Blue Tar

Figure 2. Participant Image of an Unrepaired Ceiling and Light Shining Through the Tarp

Figure 3. Participant Image of an Unrepaired Playground

Figure 4. Participant Image of a School in Need of Repair

Cultural blindness

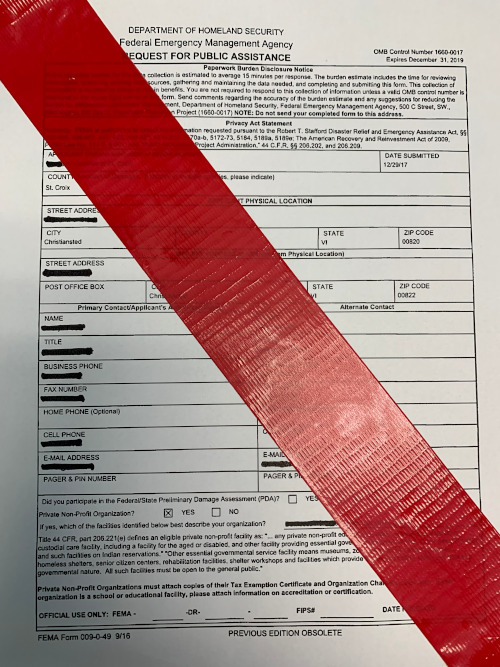

The second most common theme that emerged was the cultural blindness of disaster workers, especially regarding cultural norms that were overlooked by workers. For example, residents explained that a common part of Crucian culture included inheriting homes that were passed down to them through generations and for which they had no deed. Yet, aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) was intrinsically linked to deed possession. One participant shared, “the issues with home deeds is not new. Saw it with Hurricane Hugo. Why have we not helped people?” Another participant echoed this in reference to the issue of not having a deed, “this is cultural incompetence because it is a failure to recognize the cultural norms of the Island and to build in options for these individuals.” Participants observed that “FEMA’s requirements for assistance (i.e., deeds to property, receipts, insurance, etc...) was a hindrance to many people attaining assistance.” One participant illustrated the burdensome red tape that residents must go through to get help by placing a red tape across one of the FEMA application forms (see Figure 5).

Cultural blindness was also echoed from an environmental perspective, specifically, the lack of respect or appreciation for the environment and its worth to the community. A participant noted that “trimming [trees] to the point of mortality for purely “hazard mitigation” reasons, in my mind, showed a lack of appreciation for these trees and their value to our community.” The participant elaborated that in a hazardous tree survey that she had conducted on the island, residents overwhelmingly spoke about the meaning of trees in their lives. She said, “the trees are not just for the ecosystem services they provide (shade, fruit, etc.) but also for their place in our lives.” Figure 6 is an image of trees that are over-trimmed in an area of the country. Yet, other participants pointed out the disregard for the aesthetic of some communities compared to others during post-disaster work. For example, one participant echoed “debris sat piled up for weeks after Hurricane Maria. Someone had made the first sweep in Frederiksted but failed to follow through. Christiansted meanwhile had been cleared.” Christiansted and Frederiksted are the two towns on the island. According to participants, Frederiksted is home to many people of lower socio-economic status compared to Christiansted. Accordingly, the area is sometimes marginalized or neglected, reflecting biases in treatment.

Figure 5. Participant Image of Red Tape on a FEMA Application

Figure 6. Participant Image of Over-Trimmed Trees

Lack of Awareness of Structural Barriers

Another theme that surfaced was disaster workers’ blindness or unawareness of the socio-economic realities on the island, which can impact disaster help seeking behaviors or responses. For example, one resident wrote, “the fact that FEMA required you to register on the internet was a big joke. This isn’t the mainland this is an Island without all of the internet connections certainly not for older generations. I felt that if we can send thousands of troops into Iraq to fight a war then why wouldn’t they know how to fight the war following a Hurricane Category 5.”

One participant commented on the number of people dressed in military uniform to give aid (see Figure 7). She wrote, “these young Army guys were standing guard at the front door checking your ID to hand you a case of water.” She further wrote, “their assignment was to distribute water and food rations. The process was a NO brainer. Why would you need so many military guys to hand you a case of water?” Further, she commented on these workers’ unawareness of those with conditions that may limit their ability to get to help. “What does it take to walk door to door? The island is only 40 miles long,” she said. She added, “right down the street there were people with disabilities and seniors living within a block or two without any transportation or communication who need help.”

Figure 7. Participant Image of Boots on the Ground

Contribution to social problems

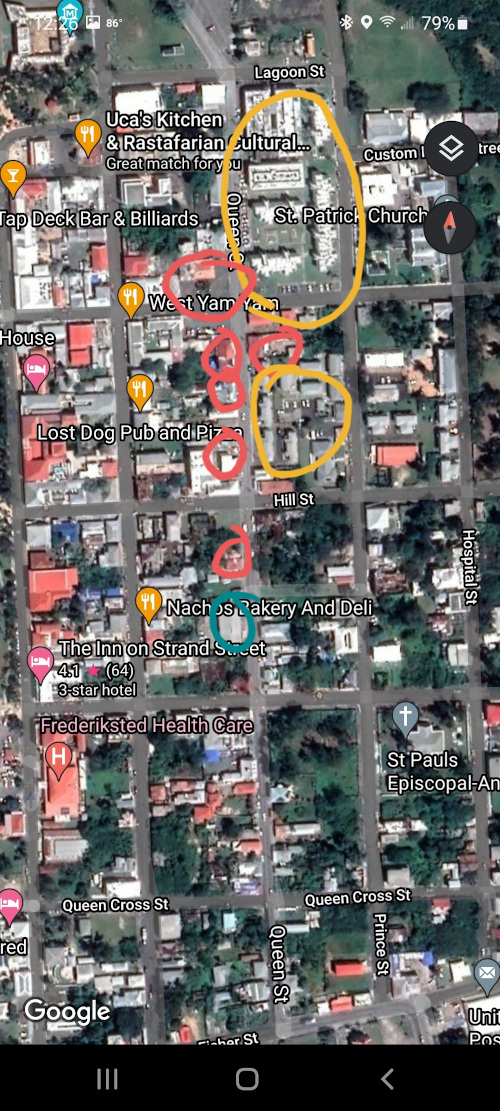

Participants highlighted that the emergence or worsening of some social problems on the island reflects the lack of cultural competence. The main social problem that was mentioned by participants is the housing crisis. Participants mentioned that the cost of housing has skyrocketed since the disaster workers were able to offer more for rent. For example, one participant said, “a housing crisis has been created as the workers drove up the price of rent. Prices skyrocketed. Now the locals cannot afford properties leaving housing essentially unavailable for them.” They explained that many foreign post-disaster workers were often willing to offer local landlords more money than the locals for their rental property. In response to this willingness to pay more, the overall cost of rental property increased. This has made it difficult for local individuals to find affordable decent rental property. Another participant echoed that, since the disaster and the influx of workers, there has been an increase in the number of bars on the island, which has attracted “questionable” activities such as gambling and illicit sexual activities (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 8. Participant Image of Street With Increasing Number of Bars in Frederiksted

Figure 9. Aerial View of Street With Increased Number of Bars (red) Close to Houses (yellow) and a fire station (blue) in Frederiksted

Bias treatment

Another theme that surfaced from the narratives and photos was the bias treatment towards some areas of the country. Participants described this as a lack of cultural competence since it reflects either a lack of respect for some people and higher regard for others based on the communities where they live. Specifically, participants felt that Frederiksted, one of two towns on the island, received less attention than Christiansted, the other town, during the recovery process. One participant used Figure 10 as an example of the bias treatment. She stated, “The ATM in Frederiksted was looted. This obviously took a very long time. Where were the national guard? She went on to write that she feels that there is no police protection in the town, the primarily Black session of the Island, because authorities think they don’t need and don’t deserve ‘protection.’” A participant also commented on the neglected repairs to the only library in Frederiksted—which serves the entire community—as compared to other facilities that serve a White or affluent population. In reference to Figures 11 and 12 a participant stated, “The extravagance of ‘The Fred’ (a Bed and Breakfast venue right across the street from the library) and the neglect of the library speaks to the populations they serve and therefore the priorities. The Fred caters mostly to Whites and clients with money. The library caters to everyday residents that use the computers because they don’t own one. Check books out on loan because they can’t afford to purchase them.” Disparity in treatment was also reflected in a discussion about the neglect to the Whim Garden, a community for seniors on a fixed income. Yet funds were raised to place—red-colored—lights across the street from it to help guide turtles back to the sand where they can hatch. According to a participant, “This is cultural incompetence at its worse. These red lights line the road between the beach front and the Markey Housing Project. What is wrong with this picture?” She added, “the failure to provide adequate care for the seniors in Frederiksted reveals a deep disregard for seniors and their well-being.”

Figure 10. Participant Photo of a Looted ATM in Frederiksted

Figure 11. Participant Photo of The Fred Bed and Breakfast

Figure 12. Participant Photo of A Neglected Library in Frederiksted

Leverage community support

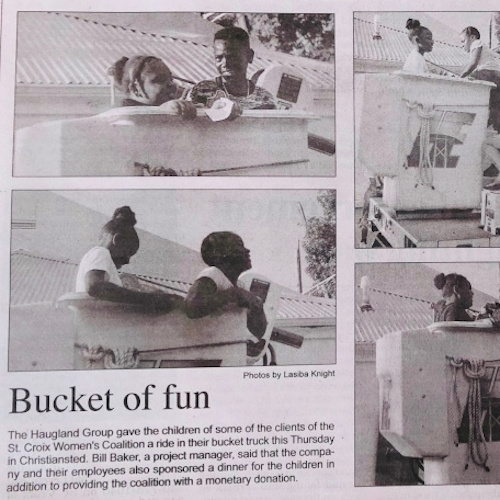

Although participants mostly captured moments of cultural incompetence, the leveraging of community efforts emerged in the photos and narratives of local disaster workers. Respondents expressed cultural competence by leveraging volunteers and community effort to help rebuild houses and mitigate damage (see Figure 13). For example, a participant talked about the “Final Nail Service,” which is a symbolic service that allows the homeowner to drive the last nail into their home to complete the repair. As a respondent expressed, “we have community caring for community,” which he believed was illustrated in Figure 14. The same respondent said, “it also speaks to teaching our children the value of taking care of your neighbor.” Another participant talked, with pride, about the amount of work that volunteers did to repair homes into livable conditions for families. For example, he said that they worked on a home that “belonged to a female senior citizen. She lived in the home post-hurricane without electricity or running water since she had nowhere else to go. Our volunteers completely redid the entire roof. We replaced some doors and windows, fixed some flooring, installed a basic kitchen and got the bathrooms working.” He further added, “it was the relationship and care that the volunteers had with the homeowner—that mutuality, partnership, and genuine concern for each other.” One community resident wrote this about Figure 15 to depict community engagement: “This is a photograph of a newspaper story/photo collage that was done about recovery workers hosting a Christmas party for children at the Women's Coalition of St. Croix's Children Center in 2019. Haugland Group came after the storms to help restore and replace our power infrastructure. Haugland Group did everything they could to display cultural competence. They asked how they could help and didn't assume they knew what was best for the community. They worked collaboratively with us to plan the party and they were really interested in giving back to the community.”

Figure 13. Participant Photo of a House Rebuilt With Volunteer Work

Figure 14. Participant Photo of Community Caring for Community

Figure 15. Participant Photo of Engaging the Community for a Bucket of Fun

Addressing Language Barriers

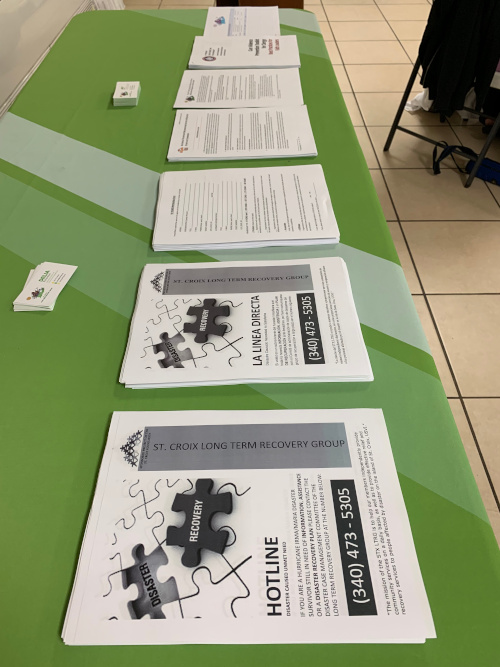

Another theme that emerged to reflect cultural competence was the availability of disaster related information in multiple languages. Notably, flyers distributed by the LTRG on the island, were available in multiple languages. According to one disaster worker with the LTRG, we were “resourcing the WHOLE of the community through offering materials in various languages spoken on the island.” This he depicted in Figure 16. Another disaster worker participant, who worked for the Red Cross mentioned that she was hired with this group because of her ability to speak several different languages.

Figure 16. Participant’s Photo of Materials Offered in Different Languages

In keeping with the participatory nature of the project, the focus group participants were asked to share recommendations related to having a culturally responsive disaster recovery work. Specifically, they were asked what messages they would like to convey to disaster workers and government officials. The following recommendations were offered:

- Monitor the progress and the way post-disaster work is being done. There is a need for local government officials to monitor the progress and the way that post-disaster work is being done.

- Give community members the opportunity to provide feedback on post-disaster work.

- Identify cultural ambassadors in different fields to work alongside and help non-Crucian workers (such as non-islanders from the United States) as they do post-disaster work.

- Pay greater attention to vulnerable populations, such as people with disabilities. For example, their homes should be documented and shared with the relevant disaster agencies so that they could be easily reached in the time of a disaster. There should be representatives from the disability community on a planning committee with FEMA.

- Establish a robust network of community members in the community so that information about a disaster can be easily conveyed.

Discussion

Findings from the photovoice projects show that most community residents had negative views towards the post-disaster work. The themes of neglect, cultural blindness, unawareness of structural barriers, bias treatment, and contribution to social problems emerged from the photovoice project. Using the Cross et al. (1989) cultural competence continuum framework, most of these themes could be conceptualized as cultural incapacity and cultural blindness. Cultural incapacity would be reflected in the theme of neglect and bias treatment. This shows behaviors that overlook the interest and needs of populations regardless of their differences. The themes of cultural blindness, unawareness of structural barriers, and contributions to social problems would reflect the phase of cultural blindness. According to Cross et al. (1989), this phase overlooks the role of social identity and context in shaping outcomes for individuals and communities. The positive themes that emerged reflect Cross et al.’s (1989) phase of cultural competence. For example, having flyers in different languages and engaging the community indicate that the workers see culture and community as integral to the recovery process. None of the themes appear to reflect the final phase of cultural proficiency, in which diversity is held in high esteem and is used to guide the mission of the work. In addition to expressing their perceptions on the extent of cultural competence, study participants offered recommendations to promote culturally competent work in disaster recovery. The recommendations highlighted the call for advancing the voice of the local community in disaster work. Specifically, allowing them to share in the decision-making as well as to provide feedback on completed work. The recommendation also highlights the call for greater collaboration between the workers and the community. This includes identifying cultural ambassadors in different fields to work along with the workers.

Conclusion

Key Findings

The current study makes a notable contribution to literature on cultural competence and disaster work in the Caribbean. The findings of the photovoice project indicate that community residents mostly believe that disaster workers are not culturally proficient in their work. Specifically, residents echoed that the work showed neglect, cultural blindness, unawareness of structural barriers, bias treatment and contribution to social problems. Fewer positive views were expressed, through themes such as leveraging community support and addressing language barriers. The disaster workers were more likely than the community residents to express these positive views.

Implications for Public Health Practice

The results from this study have implications for public health, which “refers to all organized measures (whether public or private) to prevent disease, promote health, and prolong life among the population as a whole. Its activities aim to provide conditions in which people can be healthy and focus on entire populations, not on individual patients or diseases. Thus, public health is concerned with the total system and not only the eradication of a particular disease” (World Health Organization (WHO), 201124). As disasters continue to impact every corner of the globe, disaster workers will be called upon to travel to different communities and countries with which they are unfamiliar. Further, they will be interacting with disaster survivors who have very different backgrounds from them. This reality begs that cultural competence training be an integral part of the preparation to do disaster-related work with diverse local communities around the globe. Disaster work that is devoid of cultural competence could hinder the public health focus, which according to WHO (2011) is to prevent disease, promote health, and prolong life among all people.

Given that public health is concerned with the “total system,” efforts to enhance cultural competence should be made at each stage of the disaster work (mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery) and at each level of work (government, volunteer, and organization). In other words, a wholistic approach to cultural competence for public health is needed. This should begin with an awareness and acceptance of cultural differences. Individuals and organizations should then explore their positionalities and biases as these can impact how much effort they put into trying to promote the health, and well-being of all people. They should then explore strategies to build their cross-cultural skills so that they can deliver effective services to promote well-being. One way to address this is to strengthen connections with local individuals or organizations that are knowledgeable about the cultural norms and expectations within the community.

Dissemination Plan

It is important that findings from community based participatory research reach back to the community. Presentations have already been scheduled with many of the community organizations that assisted with recruitment. These include the Rotary clubs of Mid-Isle and Harborside, and the women’s coalition group. Efforts will also be made to present the information to the LTRG of St. Croix. Several university students in St. Croix were study participants in the photovoice project, which provides the opportunity to present the findings and hold discussions in an academic space. Social work students in the social sciences department will gain a deeper understanding of cultural competence—a key dimension of social work education—in disaster recovery, which is a growing area of social work practice. An abstract on this project was submitted and accepted for presentation at the Council on Social Work Education’s Annual Program Meeting in November 2021. This research has implications for social work teaching on cultural competence and disaster work.

Limitations

The current study is instructive with regards to cultural competence in post-disaster recovery. Nonetheless, there were several limitations. The first is the sample size. Although qualitative studies generally comprise small sample sizes, this research team had expected to have a larger sample size for the photovoice. A larger sample size would have allowed for a deeper understanding of residents’ perceptions of cultural competence in disaster work. This smaller sample size prohibited robust comparison between the disaster workers and the community residents. The challenge of obtaining a larger sample was precipitated by the research team’s inability to travel to St. Croix due to COVID-19 constraints. Another limitation is related to the novelty of the photovoice methodology. Although participants were told about the autonomy to express their own perceptions of cultural competence through the photos they selected, some participants expressed difficulty in finding photos. Specifically, they said they were not sure if they were taking the “right photos.” This required the researchers to reassure the participants throughout the process that there were no right or wrong photos and that they were empowered to decide how they wanted to express their perceptions. This limitation was noted by previous photovoice studies (Wendel et al., 201925) and highlights the demanding nature of the photovoice methodology. Another limitation was the number of photos that individuals submitted. They were encouraged to take as many as they would like, but no fewer than three. Many participants appeared to aim for three photos and noted that the pandemic hindered them from moving out and capturing more photos. Nonetheless, the researchers believe that the range of themes that emerged are instructive of cultural competence in post-disaster work. Yet, another limitation is the sampling designed used nonprobability sampling. Although snowball and convenience sampling are appropriate forms of sampling, they do not yield a representative sample of participants. Hence, their use could have limited the diversity of the sample.

Future Research Directions

The current study has set the basis for future research. First, future research can involve exploring the topic across multiple U.S. Virgin Islands to determine if there are geographical variations in perceptions. Further, there can be comparison between the U.S. Virgin Islands and an area in the United States, such as a small, predominantly rural, or minority community. Other research can explore the effectiveness of cultural competence training on post-disaster work.

References

-

Mack, D., Brantley, K. M., & Bell, K. G. (2007). Mitigating the health effects of disasters for medically underserved populations: Electronic health records, telemedicine, research, screening, and surveillance. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 18(2), p. 432-442 ↩

-

St. Croix Facts and History. (2021). VI Now. https://www.vinow.com/stcroix/history/ ↩

-

St. Croix History and General Information. (2020). St.CroixTourism.com. http://www.stcroixtourism.com/aboutstcroix.htm ↩

-

Santiago, C. (2017, December 4). 75 days after Maria, this is life in St. Croix. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2017/12/03/us/us-virgin-islands-maria-recovery-trnd/index.html ↩

-

Cross, T., Bazron, B., Dennis, K., & Isaacs, M. (1989). Towards a culturally competent system of care, Volume 1. Washington, DC: CASSP Technical Assistance Center, Center for Child Health and Mental Health Policy, Georgetown University Child Development Center. ↩

-

Remington, Christa L., (2017). The cultural competence of response & recovery workers in post-earthquake Haiti. FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3455. ↩

-

Warfa, N., Chalangary, J., Amour, A., Mollica, R., Bhui, K. (2014). Cultural competence psychological interventions for psychotrauma following natural disasters: an international perspective. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of Treatment Evaluation. ↩

-

Dickinson, E. (2012). Addressing Environmental Racism Through Storytelling: Toward an Environmental Justice Narrative Framework. Communication, Culture and Critique, 5, 57–74 ↩

-

Israel, B.A., Schulz, A.J., Parker, E.A. & Becker, A.B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173-202. ↩

-

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education and Behavior, 369-387. ↩

-

Strack, R., Lovelace, K., Jordan, T., & Holmes, A. (2010). Framing photovoice using a social-ecological logic model as a guide. Health Promotion Practice, 629-636. ↩

-

Annang, L., Wilson, S., Tinago, C., Sanders, L., Bevington, T., Carlos, B., Cornelius, E., Svendsen, E. (2016). Photovoice: Assessing the long-term impact of a disaster on a community’s quality of life. Qualitative Health Research, 26(2), 241–251. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315576495 ↩

-

Bishop J., Robillard L. & Moxley D., (2013). Linda’s story through photovoice: Achieving independent living with dignity and ingenuity in the face of environmental inequities. Practice: Social Work in Action 25, 297–315. ↩

-

Schumann, R., Binder, S., & Greer, A. (2019). Unseen potential: photovoice methods in hazard and disaster science. GeoJournal 84(6) 273-289. doi:10.1007/s10708-017-9825-4 ↩

-

Yoshihama, M., & Yunomae,T. (2018). Participatory Investigation of the Great East Japan Disaster: PhotoVoice from Women Affected by the Calamity. Social Work, 63(3). doi:10.1093/sw/swy018 ↩

-

Baum, F., MacDougall, C., & Smith, D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health ,60(10), 854-857. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028662 ↩

-

Jonkman, S. N. (2005). Global perspectives on loss of human life caused by floods. Natural Hazards, 34, 151–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-004-8891-3 ↩

-

Shumba, T.W. & Moodley, I. (2018). Part 1: A review of using photovoice as a disability research method: Implications for eliciting the experiences of persons with disabilities on the Community Based Rehabilitation programme in Namibia. African Journal of Disability, 7(0), 418, doi: 10.4102/ajod.v7i0.418 ↩

-

Wang, C. (1999). Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health, 8(2), 185-192. doi:10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185 ↩

-

Sethi, B. (2016). Using the eye of the camera to bare racism: A photovoice project. AOTEAROA New Zealand Social Work, 28(14) 17-28 ↩

-

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum. ↩

-

Kerstetter K. (2012). Insider, outsider, or somewhere in between: the impact of researchers’ identities on the community-based research process. Journal of Rural Social Sciences. 27(2):99–117. ↩

-

Muhammad, M., Wallerstein, N., Sussman, A., Avila, M., Belone, L., & Duran, B. (2015). Reflections on Researcher Identity and Power: The Impact of Positionality on Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Processes and Outcomes. Critical Sociology, 41(7-8) 1045-1063. doi: 10.1177/0896920513516025 ↩

-

World Health Organization (2011). Glossary of globalization, trade and health terms. [http://www.who.int/trade/ glossary/en/](http://www.who.int/trade/ glossary/en/) ↩

-

Wendel, M., Jackson, T., Ingram, M., Golden, T., Castle, B., Ali, N., & Combs, R. (2019). Yet we live, strive, and succeed: Using photovoice to understand community members’ experiences of justice, safety, hope, and racial equity. A Journal of Community-Based Research and Practice. 2(1):9, 1–16. ↩

Constance-Huggins, M., & Sharpe, A. (2021). Photovoice and Cultural Competence in Disaster Recovery in St. Croix (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 1). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/photovoice-and-cultural-competence-in-disaster-recovery-in-st-croix