Public Trust, Community Resilience, and Disaster Response in the U.S. Virgin Islands

Publication Date: 2022

Executive Summary

Overview

In any emergency, crisis or disaster, local governments have the primary authority and responsibility to provide an effective response. A government-led emergency response includes planning, overseeing, and supporting first response, relief, recovery, and resilience efforts, in concert with the distribution of necessary public services (e.g., food, shelter, and medical services). Furthermore, the type and nature of the crisis or disaster are significant factors in planning and cultivating an emergency response. Thus, a public health emergency response (PHER) is a government-led collaborative effort between public health and healthcare systems and affected communities.

U.S. territory governments often experience delayed and indirect support from the U.S. mainland during disaster situations, and, as such, must absorb the full burden of stewarding the response. Moreover, the increase in extreme weather events in the region due to climate change pose serious risks to public health. As a result, there is an urgent need to improve public health response in the U.S. territories. This project contends that improving public trust in response is a critical element in achieving this overall goal. However, research on public trust is usually focused on the national or state level and there is a dearth of information on the U.S. territories or smaller local communities.

We define public trust of PHER as a community’s firm belief and confidence in the reliability, truth, ability, or strength of government-led response and recovery efforts. Public trust can ensure the willingness of local communities to support and cooperate with public health emergencies officials. Public trust can also be seen as a crucial element in community resilience. Community resilience is the capacity of a group of people to withstand and recover from an emergency, crisis, or disaster. Thus, public trust is an extremely valuable form of social capital for territorial governments.

Research Questions

The following research questions guided this study:

- What are the determinants of public trust in the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) government’s PHER?

- What are the determinants of USVI community resilience?

- What participant characteristics are associated with public trust of the USVI PHER?

- Is there a relationship between public trust in the USVI government’s PHER and perceptions of community resilience?

- How can the USVI government improve trustworthiness during a public health emergency?

- What government or community services and practices should be added to USVI disaster recovery?

- Which trusted community-based organizations, charities or nonprofits have played an important role in USVI disaster response?

Research Design

Data was collected using an online survey of USVI adult residents. Survey questions were drawn from the U.S. Virgin Islands public trust assessment scorecard (USVI SCORE) and the Conjoint Community Resiliency Assessment Measure (CCRAM) instruments. The research project also explored the socio-demographic characteristics associated with USVI residents’ perceptions of public trust and three qualitative questions. USVI adult residents were invited to participate in the survey through advertisements on social media and local online media sources. The preliminary data analysis was based on a sample size of 388 responses. SPSS statistical software and ATLAS.ti software were used in the analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, respectively. Factor Analysis, correlation, and content analysis were used to examine the research questions.

Findings

Based on the research questions posed, our preliminary analysis found that there were two types of public trust in PHER and two types of community resilience. There were strong to medium positive correlations between the types of public trust in PHER and community resilience. This project also identified transparency, communication, and strong governmental position in the community as critical to advancing the USVI government’s trustworthiness during a public health emergency.

Public Health Implications

Based on our findings, we recommend that local public health emergency response efforts adopt a strong community involvement approach. A strong community involvement approach to PHER can be achieved by expanding government-led collaborations and partnerships with organizations that the community find trustworthy. Correspondingly, the cultivation of a strong community involvement approach involves establishing relationships with community leaders and organizations. Community leaders should be actively involved in policy making, administrative planning, and decision-making. Furthermore, the fostering of a strong community involvement approach to PHER also requires sustainable investments in systems that provide actionable community data and necessary public services. Finally, PHER must be reflective of resident needs. Particularly, we found that there is a need for the government of USVI to provide mental health crisis care in the aftermath of disasters. Establishing a mental health crisis response could help strengthen public trust and USVI PHER.

Introduction

Public trust is often strongly associated with politics, specifically the credibility and trustworthiness of politicians, political parties, and elected officials (Dimitriu, 20201). However, public trust is more than just an indicator of political accomplishments. Public trust is also social capital and confidence in the government's capacity to respond to public threats and disasters (Gozgor, 20212). It can also be used to determine citizens’ willingness to comply and adhere to government mandates and efforts. Public trust provides an important lens to examine the government’s efforts to effectively address public health disasters. Public health disasters can be described as public health crises with dire and catastrophic social consequences (e.g., loss of life, diminished health, and reduction or failure of health services) (Afolabi & Sodeke, 20183). A public health disaster is caused by human-initiated or natural hazards and has the potential to severely burden and threaten social and economic infrastructures and the health and security of communities.

Therefore, local governments have the responsibility of developing and employing effective strategies in public health emergency response (PHER). To address a public health disaster, PHER includes complex collaborative partnerships between the public health department, first responder systems, healthcare systems, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and local communities. PHER is also responsive to the catastrophic geographic and socio-economic consequences related to public health disasters. In the past decades, the progression of public health disasters has underscored a persistent need to find new context to explore and improve PHER.

While crisis management has shown the importance of communication, services, resources and accuracy of information as vital aspects of PHER, this project contends the significance of public trust. Public trust of PHER is the community’s firm belief and confidence in the reliability, truth, ability, or strength of government led PHER. Public trust of PHER can be considered as a social catalyst to strengthen necessary and constructive relationships between public health responders and the public, during a public health disaster. Accordingly, this project provides further opportunity to address knowledge gaps related to public trust of PHER within U.S. territories. This study also showcases an empirical approach that can explore the relationships between public trust of US territorial PHER and community resilience.

Literature Review

Public Trust of Public Health Emergency Response

Kim et al. (20204) contended that the nature of PHER is often ambiguous and uncertain. Ambiguity of PHER occurs due to a lack of clear interpretation about appropriateness or exemplariness of response by all community stakeholders (i.e., government, residents, neighborhoods, businesses, nongovernmental organizations). PHER has come to mean many different things to many different people. Characterizing PHER as a trust in government offers a more defined and measurable interpretation. Kumar et al. (20215) described public trust of government as the provision of necessary governance and services needed for the socio-economic development of a community. Henderson et al. (20206) purported that public trust of government has a direct impact on the success of PHER. Governments, especially at the local level, are the first line of response and defense to public health disasters and emergencies. Salim et al. (20177) noted that “governments that enjoy greater levels of public trust can function more easily and effectively” (p. 348). Eisenman et al. (20128) acknowledged that public trust is a multifactorial construct that centers around the primary principle that “a person’s interests will be cared for by another entity” (p. 2). Bouckaert (20129) contended that there are three dimensions of public trust in government (macro, meso, and micro).

At the macro-level, public trust of government is directly connected to a belief in elected government officials, socio-political leaders, and political institutions (Bouckaert, 2012). Macro-level public trust of government is also linked to democratic civic culture, satisfaction, and accountability (Bauer, 201810). Salminen and Norrbacka (201011) offered support that public trust in the political system is rooted within citizens’ belief that elected government officials have a responsibility to be trustworthy. Van de Walle et al. (200812) acknowledged that in the 1990s, public trust became more of a political discourse. They observed that political performance and scandals had more of an effect on public trust than public sector performance. Similarly, Keele (200413) saw public trust as a factor of political popularity and important to elections. Keele (2004) offered that “a voter will trust his or her representative if he or she has evidence that the politician has the integrity and capacity to meet the voter’s expectations” (p.7). Bok (200114) asserted that the withdrawal of public trust in government could have a disadvantageous impact on the functioning of government and societal cohesion.

From a meso-level standpoint, public trust is rooted in objects, authority, and institutions that exemplify effective service delivery. Bouckaert (2012) described meso-level public trust in government as related to public service systems and public policy capacity (Ingrams, 201815). Public services and public policy can be described as all activities provided by the government, as a service provided, to fulfill the needs of the public (Purnomo & Qumariah, 201916). Blair et al. (201717) directly identified public trust as the vein of citizen’s willingness to collaborate with local government and public institutions. Public trust has the capacity to guarantee public cooperation, adherence, and compliance. The standards for achieving meso-level public trust include credibility, reliability, intimacy, and orientation (Purnomo & Qumariah, 2019).

Additionally, public administration is a contributor to meso-level public trust in government. Goodsell (200618) noted that public administration’s contribution to public trust tends “to be invisible because most of its contribution is at a routine or below-the-surface level” (p. 633). However, public trust in public administration is derived from due process. Van de Walle and Migchelbrink (202019) offered that due process entails administrative impartiality or absence of corruption. Ultimately, meso-level public trust in government is firmly rooted in a belief in the ability of government to provide the necessary benefits to its citizens.

Finally, public trust in government, at a micro-level, is based on individual experiences and the direct impact that government has on the daily lives of citizens. Park and Cho (200920) offer the standpoint that micro-level public trust is relational. This means that citizen’s trust of government is based on taking a risk of confidence in the government’s “benevolence, honesty, reliability and integrity” (Park & Cho, 2009, p. 4). Gozgor (2021) shared that in periods of crisis and uncertainty, citizen’s relational trust in government can be discerned as a social contract of cooperation and collaboration to which both parties must uphold. Park and Cho (2009) also added that micro-level public trust is determined based on levels of public satisfaction. Public satisfaction requires the government to consider public feelings at the core of governmental response and service delivery. Akinboade et al. (201221) spotlighted public satisfaction as a public expectation and public perception of government performance. They argued that public trust is an inverse relationship between public expectations and perceptions of performance (2012). However, public satisfaction is dependent on how the government manages societal crises or problems (Saidah & Rusfian, 202022). It offers a means of increasing public trust and offers an opportunity to strengthen governmental credibility and reputation.

Micro-level public trust in government is the difference between the citizen’s expectation of government responsibility and the actual provided services (Park & Cho, 2009). From this outlook, Beshi and Kaur (202023) offered that micro-level public trust in government is dependent on citizen’s belief of good governance. Good governance is a consideration of citizen preferences towards government functioning. Bouckaert and Van de Walle (200324) argued citizen preferences of good governance can diverge from actual functioning of government. Beshi and Kaur (2020) observed that public trust is more responsive to citizen perceptions of good governance. Jameel et al. (201925) identified the criteria of good governance and public trust in government as democracy, transparency, accountability, culture of law, fairness and equality, responsiveness, and integrity.

Public Trust in Public Health Emergency Response and Community Resilience

Within the context of PHER, public trust can be cultivated when communities are represented and approve of leadership involved in the response (Gutmann Koch & Han, 202026). Gutmann Koch and Han (2020) also described public trust as communities having input in the crisis standards that are implemented by the government during disasters. This means that public trust involves protecting public interest through the capacity of citizens to confer legitimacy, reputability, confidence, and compliance to community efforts (Van de Walle, 201627). Citizen trust in public health activities is significant during public health emergencies or disasters (Eisenman et al., 2012). For instance, if the public health efforts (i.e., policies, services, and workforce) are deemed trustworthy by the public, then citizens are more likely to see the value and benefit. Public trust of public health emergency response also increases active participation by local communities in public health affairs (Eisenman et al., 2012). The level of public trust in public health responses is linked to the recognizable community engagement, as well as the quality, speed, and efficiency of government performance (Malesic, 201928).

Public trust of PHER can also be perceived as strongly aligned with community resilience. Community resilience is the capacity for communities to withstand and recover from the impact of a disaster (Eachus, 201429). Cohen et al. (202030) asserted that community resilience is multi-dimensional and consists of community involvement of various stakeholders, including government, nongovernmental organizations, private sector businesses, and citizens. Community stakeholder involvement provides necessary support for building a community’s capacity to withstand and recover from disasters (Adekola et al., 202031). Public trust allows communities to come together to address societal problems with collective efficacy and within parameters that are amenable to all community stakeholders (Quarcoo & Kleinfeld, 202032). Thus, elevated levels of public trust in community stakeholder involvement can facilitate the building of community resilience (Kim, 201633).

Public Trust in At-Risk Communities

Adams et al. (202034) commented that disasters impact people differently. They noted that disparities are “driven by underlying social, economic, and political conditions” and socio-demographic patterns associated with social inequality (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity, language proficiency, class, and disability) (2020, p. 2). At-risk communities are groups who have the greatest probability of being exposed to a disaster (Davis et al., 201335). These populations are often classified as vulnerable. Vulnerable populations are social groups living in poverty, aging or late life (over 60 years), and/or have underlying health conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer) (Brücker, 200536).

The socio-demographic characteristics and histories of at-risk communities influence how their members perceive and respond to risk, as well as their views of societal response(s) to disasters (Savoia, 202137). Specifically, Gozgor (2021) found that socio-demographic determinants are significantly associated with trust in governments, with older adult citizens having more of a collective sensibility and strong trust in government than younger citizens. While there are scholars who have found age as a strong determinant of public trust, Safadi and Lombe (201138) highlighted a need for research that examines public trust in government in relation to low socio-economic status and other measures of social vulnerability. These groups generally are unable to anticipate, cope with and recover from disasters. Thus, public trust of at-risk communities must be examined to gain a necessary assessment of PHER and community resilience.

Research Design

Research Questions

Quantitative and qualitative research questions guided our research design and data analysis. The quantitative questions were the following:

- What are the determinants of public trust in the (U.S. Virgin Islands) (USVI) government’s PHER?

- What are the determinants of USVI community resilience?

- What participant characteristics are associated with public trust of the USVI government’s PHER?

- Is there a relationship between public trust in the USVI government’s PHER and perceptions of community resilience?

The qualitative questions were:

- How can the USVI government improve trustworthiness during a public health emergency?

- What government or community services and practices should be added to USVI disaster recovery?

- Which trusted community-based organizations, charities, or nonprofits have played an important role in USVI disaster response or recovery?

Data, Methods, and Procedures

This research utilized a modified cross-sectional survey method. Data was collected from residents of USVI, who were at least 18 years of age. Participation was voluntary and the web-based survey was self-administered. The data collection ensured confidentially and anonymity. The questionnaire for this study was constructed using Google Forms. The questionnaire was prepared in the English language. This e-questionnaire included a consent notice for participation in the survey. The consent notice was attached to the questionnaire's entrance page. The recruitment script for social media correspondences and informed e-consent notice provided an overview of the study, risks, and benefits as well as a statement of confidentiality.

Recruitment Strategy

Recruitment for this web-based survey involved media blasts and targeted ads on social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter. Overall, targeted ads on social media allowed for the opportunity to recruit diverse and hard-to-reach populations. The target ads for this research project included direct links to the e-survey. In addition to social media platforms, the study was advertised in the VI Consortium and VI Source, which are popular news media outlets. The project advertised in both media outlets through in-article advertising. In-article advertising provided ad placements within the news articles. Thus, all readers of the news outlet were able to view the project’s advertisement and access the e-questionnaire. (Examples of recruitment materials are available in the appendix.)

Sampling and Participants

The unit of analysis for this study was USVI residents. There are roughly 87,146 residents living in the USVI. Residents live on St. Thomas, St. John, St. Croix, and Water Islands. A total of 67,000 residents are internet users, and 32,000 are social media users (Kemp, 202139). This study utilized a convenience sample of USVI residents. As of March 11, 2022, there were a total of 407 responses. Due to incomplete or missing data in the responses, 388 usable responses were utilized.

Measures

The e-questionnaire for this project included twelve demographic items. The questionnaire also consisted of the USVI public trust assessment scorecard (USVI SCORE) and the Conjoint Community Resiliency Assessment Measure (CCRAM). There are also three qualitative items (as presented in the research question section). The USVI SCORE examines residents’ perceptions of the USVI s government’s responsibilities during public health disasters. It is important to note that the USVI score is a modified version of the COVID-19 assessment score card (COVID-SCORE-10). USVI SCORE was modified by removing all mention of COVID from the items of the COVID-SCORE-10. Our USVI SCORE included 13 items that measure public trust in PHER. Responses options for each item ranged from “completely disagree” for a minimum score of 1 to “completely agree” for a maximum score of 5. Factor analysis was used to determine reliability.

The modified version of the CCRAM is a nine-item instrument that was developed to measure community resilience (Leykin et al., 201340). The CCRAM consists of five subdomains: (a) leadership, (b) collective efficacy, (c) preparedness, (d) place attachment, and (e) social trust. (Lists of the items mentioned in this section can be found in the tables of results below.)

Data Analysis

Descriptive Statistics

We generated descriptive statistics for the demographic data using univariate statistics (i.e., frequency distributions). The variables included age, gender, ethnicity, location, health conditions, and marital status.

Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to determine dimensionality and construct validity of the USVI SCORE and CCRAM items that represent public trust of USVI government’s PHER and community resilience, respectively. Additionally, tetrachoric correlation factor analysis was a used to determine the dimensionality of health conditions reported by participants. Because the variables were coded dichotomously, tetrachoric correlation factor analysis was employed. Factors for public trust, community resilience and health conditions were interpreted based on factor loadings. Loadings can range from -1.0 to +1. Loadings above 0.6 are considered “high.” Loadings below 0.4 are considered “low.” The scores generated by factors were used as variables of public trust of PHER, community resilience, and health conditions. To validate the internal consistency of each of the statements in the identified factors, Cronbach Alpha values were generated for each subscale.

Correlation

Correlation analysis (i.e., Pearson and Spearman) was conducted to study the potential relationships between USVI residents’ perceptions of public trust in PHER, community resilience, and their demographic characteristics. The correlation coefficient r is a number ranging from -1 to +1. Associations between .5 to 1.0 were considered large. Associations ranging between .3 to .5 were regarded as medium. Small associations range between .1 to .3. A significance level of 5% (α=0.05) was used.

Content Analysis

We used content analysis to analyze the qualitative questions of the questionnaire. All the responses to the qualitative questions were thoroughly reviewed several times, then codes and categories were identified. ATLAS.ti software provided the capability of searching for the presence of certain words, quotes, themes, or concepts within the qualitative data. ATLAS.ti software also provided opportunity to code, categorize, and manage the findings. The content analysis approach allowed the research team to determine the frequency of each code.

Ethics Statement

This research project received approval from the University of the Virgin Islands Institutional Review Board on December 2, 2021 (Approval #1821972-3). The level of anonymity and confidentiality remained intact, as well as in compliance with IRB’s consent form ruling, using the approved recruitment script and e-consent notice. Additionally, a web-based format (Google e-form) was used to disseminate the project’s questionnaire. Finally, all researchers on this project are residents of the USVI and live in the research areas.

Findings

Demographic Characteristics of Survey Sample

As displayed in Table 1, most of the participants were residents of St. Thomas and St. Croix, accounting for 50% and 42%, respectively. Almost 70% of the participants identified as female. In terms of age, about 30% of participants were Millennials (currently between 25 and 40 years old). About 36% of participants fell within the grouping of Generation X (between 41-56 years old), and 24.5% of respondents were Baby Boomers (between 57-75 years old). About 58% of participants identified as African American or Black. The second largest group of participants identified as Caucasian or White at 26.5%. Regarding marital status, 37.9% reported being single, and 35.65% identified being married. In terms of health conditions, 26% of the participants suffer from hypertension/heart disease and 17.5% reported having asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or emphysema. About 39.7% of the participants reported having no pre-conditions.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents

| Location | St. Croix | ||

| St. Thomas | |||

| St. John | |||

| Water Island | |||

| Not Reported | |||

| Gender | Female | ||

| Male | |||

| Transgendered Female | |||

| Not Reported | |||

| Age | 18-19 | ||

| 20 - 29 | |||

| 30 - 39 | |||

| 40 - 49 | |||

| 50 - 59 | |||

| 60 or greater | |||

| Not Reported | |||

| Ethnicity | African American/Black | ||

| Caucasian/White | |||

| Latino/Hispanic | |||

| Other | |||

| Not Reported | |||

| Income | Less than $24,999 | ||

| $25,000-$49,999 | |||

| $50,000-$74,999 | |||

| $75,000-$99,999 | |||

| $100,000-$124,999 | |||

| $125,000-$149,999 | |||

| Greater than $150,000 | |||

| Not Reported | |||

| Marital Status | Single | ||

| Married | |||

| Widowed | |||

| Divorced | |||

| Relationship (Not Married) | |||

| Not reported | |||

| Health Conditions | Asthma, COPD, Emphysema | ||

| Diabetes | |||

| Developmental Disability | |||

| Hypertension/Heart Disease | |||

| Immunosuppressed | |||

| Physical Disability | |||

| Psychosocial/mental illness | |||

| No Pre-condition | |||

| Employment Status | Unable to work | ||

| Self-employed | |||

| Homemaker | |||

| Retired | |||

| Full-time Student | |||

| Unemployed and currently looking for work | |||

| Employed part time | |||

| Employed full time | |||

| Not Reported | |||

Determinants of Public Trust in Public Health Emergency Response

We performed EFA using the thirteen items in the USVI SCORE to explore Research Question 1 (what are determinants of public trust in the USVI government’s PHER?). The analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .924 and p value less than .001. The analysis output for public trust, as seen in Table 2, highlighted the existence of two factors displaying strong factor loadings. Based on the factor loadings, Factor 1 grouped together determinants that represent macro- and meso-level views of public trust of PHER. These determinants are contextually political and attuned to governmental authority, actions, and institutions that exemplify effective service delivery during a public health emergency. Based on the factor loadings, Factor 2 grouped together determinants that represent micro-level views of public trust of the USVI government’s PHER. This aspect of public trust represents how PHER directly impacts on the daily lives of citizens.

Table 2. Results From Factor Analysis of U.S. Virigin Islands Assessment Scorecard Measures

Macro- and Meso-Level Viewsa |

Micro-Level Viewsb |

|||

| I trust public officials (governor, commissioners, legislators) to act responsibly in the service of community's interest. | ||||

| The USVI government is willing to help me, and my family meet our daily needs in terms of income, food, and shelter. | ||||

| The USVI government communicates clearly to ensure that everyone has the information they need to protect themselves and others, regardless of socioeconomic level, migrant status, ethnicity, or language. | ||||

| The USVI government has a strong public health preparedness team that includes public health and medical experts to manage community response. | ||||

| I trust that USVI public health professionals (e.g., public health officials, epidemiologists, community health workers, social workers, doctors, nurses, paramedics) are prepared to perform their duties to address persistent and emerging public health problems. | ||||

| The USVI government provides residents with full access to necessary healthcare services. | ||||

| The USVI government provides special protections to vulnerable groups at higher risk such as the elderly, the poor, migrants, prisoners and the homeless. | ||||

| The USVI government ensures that healthcare workers are safe and protected. | ||||

| The USVI government provides mental health services to help people suffering from loneliness, depression, and anxiety. | ||||

| I trust the government's reports on the spread of epidemics, and the statistics on the number of illnesses and deaths. | ||||

| The government mandates (i.e., vaccination, wearing masks, social distancing, curfews) are effective. | ||||

| The USVI health care system (i.e., hospitals, pharmacies, laboratories, medical private practices, and clinics) can ensure a healthy community. | ||||

| The government and the business community work together to safely restart the economy. | ||||

aCronbach’s Alpha for variable 1 = .885 (p=.001).

bCronbach’s Alpha for variable 2 = .864 (p=.001).

After isolating factors of public trust, EFA was used to construct both variables of public trust. Table 2 showcases the strengths of each factor. Factor scores from the EFA analyses were used as variables. The variable formed from the factor 1 had a Cronbach’s alpha of .885 and significance of .001. The variable formed from the factor 2 had a Cronbach’s alpha of .780 and significance of .001.

Determinants of Community Resilience

We performed EFA using the nine items of CCRAM to assess Research Question 2 (what are the determinants of USVI community resilience?). The analysis had a strong Cronbach’s alpha of .852 and significance of .001. The analysis output, as seen in Table 3, showcases the existence of two factors displaying strong factor loadings. Factor 1 is inclusive of collective efficacy, place attachment and social trust. Factor 2 is inclusive of leadership and preparedness. After isolating factors of community resilience, EFA was used to construct both variables of community resilience. Table 3 showcases the strengths of each factor. Factor scores from the EFA analyses were used as variables. Variable 1 is representative of community resilience that is community-led. Variable 1 has a Cronbach’s alpha of .861 and a significance of .001. Variable 2 is representative of community resilience that is government-led. Variable 2 has a Cronbach’s alpha of .780 and a significance of .001.

Table 3. Results From Factor Analysis of Conjoint Community Resiliency Assessment Measures

Community-Leda |

Government-Ledb |

||||

| Leadership | The USVI government functions well with the local community. | ||||

| I trust the decisions of elected officials. | |||||

| Collective Efficacy | I can count on people in my community to help me in a crisis situation. | ||||

| People care for one another. | |||||

| Preparedness | The USVI is prepared for an emergency. | ||||

| Residents are aware of their roles in an emergency. | |||||

| Place Attachment | I am proud of where I live. | ||||

| I have a sense of belonging to my community. | |||||

| Social Trust | Good relationships exist between various groups in the USVI community. | ||||

aCronbach’s Alpha for variable 1 = .861 (p=.001).

bCronbach’s Alpha for variable 2 =.780 (p=.001).

Respondent Characteristics Associated With Public Trust in the U.S. Virgin Islands Government-Led Public Health Emergency Response

To explore Research Question 3 (what demographic characteristics of participants are associated with their views on public trust of the USVI government’s PHER?), a correlation analysis (Spearman) was conducted to determine links between demographics of respondents and their level of public trust of the USVI government’s public health emergency response. Table 4 presents the relationships between the two public trust variables of the study (macro and meso-level, and micro-level) and select demographic variables (age, gender, ethnic identity, location, employment status, marital status, and health conditions). The factor scores for health conditions were generated using tetrachoric correlation factor analysis of selected variables of health conditions (factor loadings): asthma (.495), diabetes (.628), immunosuppression (.504), physical disability (.501), hypertension/heart disease (.552). The factor loading of these variables received a Cronbach’s Alpha of .612.

Table 4. Results From Correlation Analysis of Demographic Characteristics Associated With Public Trust in Government-Led Public Health Emergency Response

(macro/meso-level) |

(micro-level) |

||

| Age | r | ||

| p-value | |||

| Gender | r | ||

| p-value | |||

| Ethnic Identity | r | ||

| p-value | |||

| Location | r | ||

| p-value | |||

| Employment Status | r | ||

| p-value | |||

| Annual Household Income | r | ||

| p-value | |||

| Marital Status | r | ||

| p-value | |||

| Health Conditions | r | ||

| p-value | |||

As seen in Table 4, weak correlations were found between age (.107), location (.199), household income (.146) and Variable 1 of public trust in PHER (macro- and meso-level). Variable 2 of public trust in PHER (micro-level) had weak correlations between gender (.120), ethnicity (.105), and location (.167). Although the demographic associations were weak, location had the strongest association between both variables of public trust in PHER. Thus, consideration must be given to a resident’s location (St. Croix, St. Thomas, St. John, and Water Island) as having an influence on both forms of public trust. Regarding exploration of associations between vulnerability and public trust, age, gender, and annual household income could be considered as possible demographic characteristics.

Association Between Public Trust and Community Resilience

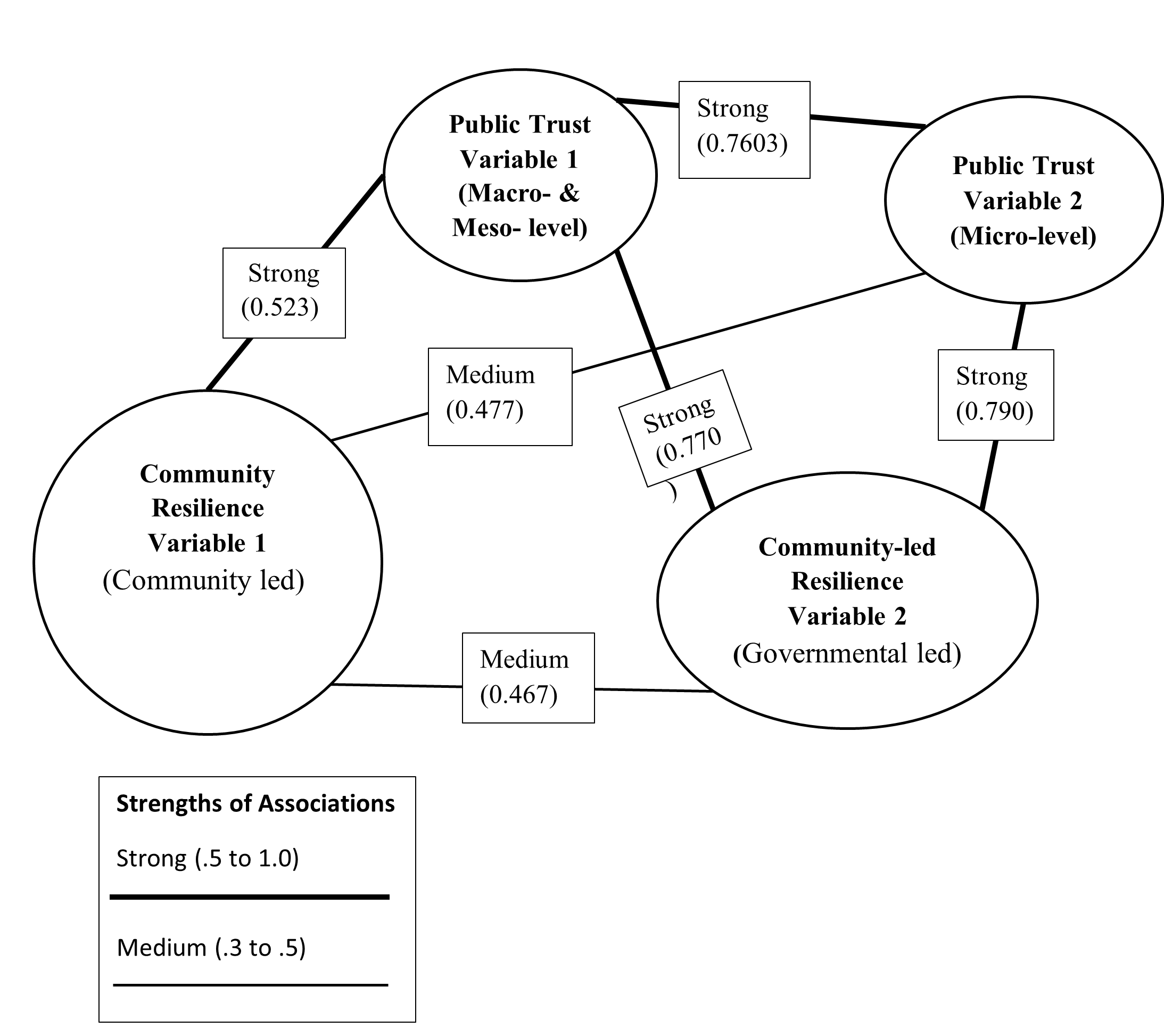

To examine Research Question 4 (is there a relationship between public trust in the USVI government’s PHER and perceptions of community resilience?), a correlation analysis was conducted. The results are presented in Table 5. Both variables for public trust have an association of .763. Variable 1 of public trust (macro/meso-level) and Variable 1 of community resilience (community led) have a correlation of .523. Variable 1 of public trust (macro/meso-level) and Variable 2 of community resilience (government led) have a correlation of .770. Variable 2 of public trust (micro-level) and Variable 1 of community resilience (community led) have a correlation of .477. Variable 2 of public trust (micro-level) and Variable 2 of community resilience (government led) have a correlation of .790. Both variables of community resilience have an association of .467. All associations were significant.

Table 5. Results From Correlation Analysis of the Association Between Public Trust and Community Resilience

| Public Trust Variable 1 | r | ||||

| p-value | |||||

| Public Trust Variable 2 | r | ||||

| p-value | |||||

| Community Resilience Variable 1 | r | ||||

| p-value | |||||

| Community Resilience Variable 2 | r | ||||

| p-value | |||||

The results of the correlation analysis were used to create a conceptual model that displayed the relationships between Public Trust of the USVI government’s PHER and community resilience. Figure 1 presents strong (.5 to 1.0) and medium (.3 to .5) associations between the variables of public trust and the variables of community resilience. There were strong relationships between both public trust variables. While the EFA of the thirteen determinants of public trust might have created two separate variables (see Table 2), they are both strongly related. This relationship provides an opportunity to draw attention to dimensional variations—macro-, meso-, and micro-level—in public trust of the USVI government’s PHER.

Figure 1. Associations Between Public Trust and Community Resilience

As seen in Figure 1, there was a medium relationship between the two community resilience variables. In fact, the association between the variables of community resilience was the weakest in the model (.467). The items that construct Community Resilience Variable 1 were centered on resident involvement and connections with the community of the USVI. On the other hand, the items aligned in Community Resilience Variable 2 centers around governmental responsibilities and contributions to community resilience. Not only are there clear differences between these two aspects of community resilience, but a case can be made that residents perceive their involvement in community resilience to be less associated with their trust of USVI government’s PHER. This argument is supported based on Community Resilience Variable 1’s weaker association with the two public trust variables than Community Resilience Variable 2.

Qualities Associated with Government Trustworthiness

To address Research Question 5 (how can the USVI government improve trustworthiness during a public health emergency?), content analysis was utilized. Participants’ responses (i.e., words, phrases, sentences, or whole paragraphs) were sorted into three categories: (a) strong governmental presence in community, (b) transparency, and (c) communication. The most suggested means of improving USVI government trustworthiness was strong governmental presence in community. Strong governmental presence received 89 words, phrases and/or sentences. Strong governmental presence entails government having a focus on recognizably serving the community.

The second category, transparency, received 87 entries. Transparency is defined as government’s willingness to share information and reveal its inner workings to the public. Therefore, transparency should be considered as a means of government building trustworthiness within PHERs. The final major category was communication, with sixty entries. Inclusive of communication, respondents were concerned with trust, listening, and attention by government. Over twenty respondents also identified concerns related to the sharing of information and accessing resources as an issue related to improving the trustworthiness of USVI government during public health emergencies. While there were many responses to this qualitative question, the following are selected responses that underscore community stakeholder views on improving USVI government’s trustworthiness during a public health emergency:

Government should work closer with the community. This will ensure that there is mutual understanding of the community to which government is trying to serve our needs. Government must offer the community what they need, instead of what they think we need.

Government should look out for its people. They must ensure that everyone is covered and have what they need. They should establish efficient and effective health care systems during regular times, to demonstrate their ability to handle disasters, like COVID.

The USVI government can improve trustworthiness during public health disasters by having a preparedness plan and doing frequent drills to ensure that key partners know their roles and how to carry out those roles during a disaster. A lot of times, a plan is in place, but it is outdated or not communicated clearly to those involved. Therefore, the government is often in reactive mode instead of a proactive mode.

Service Gaps Identified by Respondents

To examine Research Question 6 (what government or community services and practices should be added to USVI disaster recovery?), content analysis sorted two categories of services and practices that participants felt should be added to USVI disaster recovery: (a) improvement and expansion of healthcare and wellness services, and (b) expansion of public services. Significantly, sixty-eight respondents identified the importance of expanding the provision of healthcare services. Along with healthcare expansion, respondents brought attention to a need for better trained healthcare professionals. Participants also shared the need for post-disaster assistance for people with disabilities as well as seniors living alone. Furthermore, thirty-seven respondents identified mental health services (e.g., counseling, therapy, support groups and case management services) to be a vital need, during and in the aftermath of public health emergencies. As one respondent expressed, “Mental health! Lots of it!”

Additionally, participants shared a need for government to expand their provision of public services during disasters. Public services must be based on citizens’ needs, as opposed to what the government thinks they need. This citizen centric approach will help to increase public satisfaction and trust. Some of the public services that respondents mentioned needing during disaster recovery (e.g., advance disaster sheltering, transportation services, rental assistance, monetary support, and increase rebuilding home initiatives).

Trusted Organizations Identified by Respondents

Based on the exploration of Research Question 7 (which trusted community-based organization, charities or nonprofits have played an important role in USVI disaster response or recovery?), 87 organizations were identified (mentioned) as trusted community-based organizations, charities, or nonprofits that played an important role in USVI disaster response or recovery. With the largest number, Red Cross was mentioned 54 times. Community Foundation of the Virgin Islands was stated 23 times. Catholic Charities and My Brother’s Workshop were both mentioned 21 times. Family Resource Center and the Federal Emergency Management Agency were mentioned 15 times. The Salvation Army was mentioned 14 times. The National Guard was mentioned 13 times. Virgin Islands Territorial Emergency Management Agency (VITEMA) and Lutheran Social Services were mentioned 11 times. Overall, the USVI is filled with community organizations that can help to strengthen emergency responses to disasters.

Conclusions

Public trust of public health emergency response (PHER) has become an important topic of current mainstream public discussions. Recent public health crises have raised significant questions about the extent to which the communities can trust government-led emergency responses. Scholars, scientists, researchers, practitioners, bureaucrats, and government officials are currently searching for the best strategies to characterize, garner and utilize public trust in PHER. Accordingly, this study sought to gain an understanding of public trust related to territorial PHER. The research findings provide support of the notion that public trust in PHER is related to community resilience. The findings also offer valuable insight in PHER policy applications and implications for practice in the USVI.

Policy Applications

PHER policies, strategies and activities should be developed to strengthen relationships with community members. The empirical findings revealed a necessity for visible and strong community involvement in PHER at the administrative and policy making levels of government. Community involvement in policy making, administrative planning, and decision-making provides necessary practical insight in achieving collective efficacy. Policymakers and officials in government must develop a community approach to local governance by working with community leaders and organizations in launching efforts with PHERs. Specifically, community representation should be visible in the enactment of public health emergency taskforce. Community leaders or members from each island should be placed on the taskforce. Alternatively, a diversity, inclusion and equity community advisor council could be established that is aligned with PHER.

Implications for Practice

To create a clear path in cultivating stronger public trust in PHER, government must address the matter of presence in the community and transparency. While efforts need to focus on increased accountability, consistency, and credibility in government, the development and implementation of an effective public health emergency risk communication strategy is also needed. Effective emergency risk communication entails dissemination of information and messages to cultivate a needed belief, acceptance, compliance, appreciation, and acknowledgement by community members. Strategies for effective emergency risk communication must consider the reputation of government, scientific accuracy, socio-cultural sensitivity, the acknowledgment of uncertainties and possible misrepresentation in the provided messages, speed at which information is disseminated, alignment in communications by collaborating departments, agencies, and community agencies, and opportunities to participate, guide and/or influence community dialogue (World Health Organization, 201941; Seeger et al., 201842).

Another concern that must be addressed by government on the matter of building public trust in PHER is the improvement and expansion of public services, specifically concerning public health services. Attention must be given to ensure that public services are made accessible to all members of the community that are in need. Special consideration must be given to the vulnerable populations within the community. Our study also found that the USVI has a need for improved efforts in mental health crisis care. Mental health crisis care would require the provision of services to address concerns, such acute stress disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and bereavement. Mental health crisis care would require several services, such as treatment and intervention planning, mobile crisis response services, crisis assessments, stabilization services, residential services, and hotline/text services.

USVI public health emergency services should consider finding strategies to develop an identity that is associated with the shared social identity of communities in the aftermath of the public health disaster. In the aftermath of a public health disaster, a shared social identity of a community can create solidarity and a willingness for community members to help. Tapping into a community’s shared social identity would also sensitize PHER and its services to the unique demographic and socio-cultural attributes of the community. Consequently, there is a need for community leaders, organizations, and members to be an integral part of developing public health emergency response identity.

Limitations and Strengths

While this study makes some important contributions to research on disasters, public trust, PHER and community resilience, it is not free from limitations. The sample size of 388 participants, as compared to the population of the USVI, should be noted as a limitation. The small sample size limited the extent to the findings can be representative or generalized to the wider population of the USVI. Future research should test the model using larger sample size to confirm the results of this current research. There was also a limitation in achieving a sample size that was reflective of the socioeconomically or educationally vulnerable and disadvantaged populations in the USVI. Additionally, the potential limitations of self-reported data must also be acknowledged. Due to self-report bias, there may be limits on the validity of the findings.

In terms of analytical limitations, it is important to note that some of the limitations to using EFA. EFA assumes a linear relationship between factors. This occurrence is not always the case. Additionally, selecting and defining factor score contains some expected amount of subjectivity in decision and interpretation. This subjectivity leads to inconsistency and limits generalizability. While correlation is a great statistical method to measure associations between two or more variables, it assumes linear relationships that do not necessarily exist. Furthermore, correlation cannot interpret casual effect. Finally, due to the nature of qualitative analysis, the findings of the content analysis do not represent the views of the wider populations of USVI residents.

Future Research Directions

Even with its limitations, this preliminary study was able to obtain vital information to significantly answer the proposed research questions. The findings offer a path to understanding the variations in public trust of PHER and community resilience. This work also revealed the associations between both concepts. We are presently continuing to collect data to obtain a larger sample size for further research. A larger sample size would be more representative of the population. It would also offer enough power to conduct a more in-depth examination.

Additionally, the findings of this study spotlighted a need for future research to investigate public trust of public health professionals. Attention must be given to examining the qualities that are needed to build or solidify public trust in USVI public health professionals and first responders. Relatedly, the effort of this work also gives way to expanding the research of USVI public trust in PHER to explore concerns of community-level public distrust of healthcare, especially among disadvantaged populations. Webb Hooper et al. (201943) found that this form of public distrust is a highly complex psycho-social construct that can create obstacles in PHER. Thus, future research must be conducted to find approaches to minimize or address distrust of PHER.

References

-

Dimitriu, G. (2020). Clausewitz and the politics of war: A contemporary theory. Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(5), 645-685. ↩

-

Gozgor, G. (2021). Global evidence on the determinants of public trust in governments during the COVID-19. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17(2), 559-578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09902-6 ↩

-

Afolabi, M. O., & Sodeke, S. O. (2018). Public health disaster-related research: A solidaristic ethical prism for understanding funders’ duties. The American Journal of Bioethics, 18(11), 37-39. ↩

-

Kim, Y., Ku, M. & Oh, S.S. (2020). Public health emergency response coordination: Putting the plan into practice. Journal of Risk Research, 23(7-8), 928-944. ↩

-

Kumar, D., Pratap, B., & Aggarwal, A. (2021). Public trust in state governments in India: Who are more confident and what makes them confident about the government? Asian Journal of Comparative Politics, 6(2), 154-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057891119898763 ↩

-

Henderson, J., Ward, P. R., Tonkin, E., Meyer, S. B., Pillen, H., McCullum, D., Toson, B. Webb, T., Coveney, J. & Wilson, A. (2020). Developing and maintaining public trust during and post-COVID-19: Can we apply a model developed for responding to food scares? Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 369. ↩

-

Salim, M., Peng, X.B., Almaktary, S.Q. and Karmoshi, S. (2017) The impact of citizen satisfaction with government performance on public trust in the government: Empirical evidence from urban Yemen. Open Journal of Business and Management, 5, 348-365. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2017.52030 ↩

-

Eisenman, D. P., Williams, M. V., Glik, D., Long, A., Plough, A. L., & Ong, M. (2012). The public health disaster trust scale: Validation of a brief measure. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 18(4), E11-E18. ↩

-

Bouckaert, G. (2012). Trust and public administration. Administration, 60(1), 91-115. ↩

-

Bauer, P. C. (2018). Unemployment, trust in government, and satisfaction with democracy: An empirical investigation. Socius, 4, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117750533 ↩

-

Salminen, A., & Ikola‐Norrbacka, R. (2010). Trust, good governance and unethical actions in Finnish public administration. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 23(7), 647-668. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513551011078905 ↩

-

Van de Walle, S., Van Roosbroek, S., & Bouckaert, G. (2008). Trust in the public sector: Is there any evidence for a long-term decline? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 74(1), 47-64. ↩

-

Keele, L. (2004). Social capital, government performance, and dynamics of trust in government. American Journal of Political Science, 51(2), 241-254. ↩

-

Bok, D. (2001) The trouble with government. Harvard University Press. ↩

-

Ingrams, A. (2018). M-government. In M. Holzer, A. P. Manoharan, & J. Melitski (Eds.), E-government and information technology management: Concepts and best practices (pp. 155-182). Melvin & Leigh. ↩

-

Purnomo, S., & Qomariah, N. (2019). Improve community satisfaction and trust in the public service mal of Banyuwangi District. Prosiding CELSciTech, 4, 40-47. ↩

-

Blair, R. A., Morse, B. S., & Tsai, L. L. (2017). Public health and public trust: Survey evidence from the Ebola Virus Disease epidemic in Liberia. Social Science & Medicine, 172, 89-97. ↩

-

Goodsell, C. T. (2006). A new vision for public administration. Public Administration Review, 66(4), 623-635. ↩

-

Van de Walle, S., & Migchelbrink, K. (2020). Institutional quality, corruption, and impartiality: The role of process and outcome for citizen trust in public administration in 173 European regions. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 25(1), 9-27. ↩

-

Park, J., & Cho, K. (2009). Declining relational trust between government and publics, and potential prospects of social media in the government public relations. In Proceedings of the EGPA Conference, The Public Service: Service Delivery in the Information Age. ↩

-

Akinboade, O. A., Kinfack, E. C., & Mokwena, M. P. (2012). An analysis of citizen satisfaction with public service delivery in the Sedibeng district municipality of South Africa. International Journal of Social Economics, 39(3), 182–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068291211199350 ↩

-

Saidah, M., & Rusfian, E. Z. (2020). Hoax management of presidential staff office: An example of government public relations strategies. Jurnal Studi Komunikasi, 4(1), 32-48. ↩

-

Beshi, T. D., & Kaur, R. (2020). Public trust in local government: Explaining the role of good governance practices. Public Organization Review, 20(2), 337-350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-019-00444-6 ↩

-

Bouckaert, G., & Van de Walle, S. (2003). Comparing measures of citizen trust and user satisfaction as indicators of ‘good governance’: Difficulties in linking trust and satisfaction indicators. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 69(3), 329-343. ↩

-

Jameel, A., Asif, M., & Hussain, A. (2019). Good governance and public trust: Assessing the mediating effect of E-government in Pakistan. Lex Localis, 17(2), 299-320. ↩

-

Gutmann Koch, V., & Han, S. A. (2020). COVID in NYC: What New York did, and should have done. The American Journal of Bioethics, 20(7), 153-155. ↩

-

Van de Walle, S. (2016). NPM: Restoring the public trust through creating distrust? In T. Christensen & P. Lagreid (Eds.), The Ashgate research companion to new public management, (pp. 325-336). Routledge. ↩

-

Malesic, M. (2019). The concept of trust in disasters: the Slovenian experience. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 28(5), 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1108/dpm-11-2018-0375 ↩

-

Eachus, P. (2014). Community resilience: Is it greater than the sum of the parts of individual resilience? Procedia Economics and Finance, 18, 345-351. ↩

-

Cohen, O. , Mahagna, A. , Shamia, A. , & Slobodin, O. (2020). Health‐care services as a platform for building community resilience among minority communities: An Israeli pilot study during the COVID‐19 outbreak. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207523 ↩

-

Adekola, J., Fischbacher-Smith, D., & Fischbacher-Smith, M. (2020). Inherent complexities of a multi-stakeholder approach to building community resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 11(1), 32-45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-021-00334-w ↩

-

Quarcoo, A., & Kleinfeld, R. (2020). Can the coronavirus heal polarization? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/files/QuarcooKleinfeld_CoronavirusHealPolarization.pdf ↩

-

Kim, S. (2016). Public trust in government in China and South Korea: Implications for building community resilience. Chinese Public Administration Review, 7(1), 35-76. ↩

-

Adams, R. M., Evans, C. M., Mathews, M. C., Wolkin, A., & Peek, L. (2020). Mortality from forces of nature among older adults by race/ethnicity and gender. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(11), 1517-1526. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820954676 ↩

-

Davis, E. A., Hansen, R., Kushma, J., Peek, L., & Phillips, B. (2013). Identifying and accommodating high-risk, high-vulnerability populations in disasters. In T.G. Veenema (Ed.), Disaster nursing and emergency preparedness for chemical, biological, and radiological terrorism and other hazards (pp. 520-541). Springer. ↩

-

Brücker, G. (2005). Vulnerable populations: Lessons learnt from the summer 2003 heat waves in Europe. Eurosurveillance, 10(7), 1-2. ↩

-

Savoia, E., Piltch-Loeb, R., Goldberg, B., Miller-Idriss, C., Hughes, B., Montrond, A., Kayyem, J., & Testa, M. A. (2021). Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Socio-demographics, co-morbidity, and past experience of racial discrimination. Vaccines, 9(7), 767, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9070767 ↩

-

Safadi, N. S., & Lombe, M. (2011). Exploring the relationship between trust in government and the provision of social services in countries of the global south: The case of Palestine. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(4), 403-411. ↩

-

Kemp, S. (2021). Digital 2021: The United States Virgin Islands [Slide Show]. DataReportal.com. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-united-states-virgin-islands ↩

-

Leykin, D., Lahad, M., Cohen, O., Goldberg, A., & Aharonson-Daniel, L. (2013). Conjoint community resiliency assessment measure-28/10 items (CCRAM28 and CCRAM10): A self-report tool for assessing community resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52(3-4), 313-323. ↩

-

World Health Organization. (2019). Risk communication strategy for public health emergencies in the WHO South-East Asia Region: 2019–2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326853/9789290227229-eng.pdf ↩

-

Seeger, M. W., Pechta, L. E., Price, S. M., Lubell, K. M., Rose, D. A., Sapru, S., Chansky, M. & Smith, B. J. (2018). A conceptual model for evaluating emergency risk communication in public health. Health Security, 16(3), 193-203. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2018.0020 ↩

-

Webb Hooper, M., Mitchell, C., Marshall, V. J., Cheatham, C., Austin, K., Sanders, K., Krishnamurthi, S., & Grafton, L. L. (2019). Understanding multilevel factors related to urban community trust in healthcare and research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3280-3295. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183280 ↩

Hendrickson, K. A., Francis, K. A., & Clarke, A. M. (2022). Public Trust, Community Resilience, and Disaster Response in the U.S. Virgin Islands (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 18). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/public-trust-community-resilience-and-disaster-response-in-the-u-s-virgin-islands